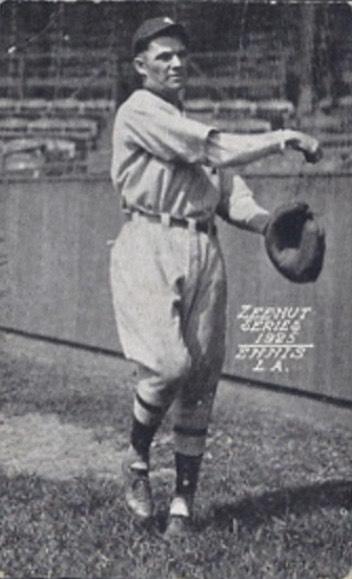

Russell Ennis

Catcher Russell “Hack” Ennis played in one major-league baseball game. Though he did not get to bat, he was behind the plate when Ty Cobb got his last hit in a Detroit Tigers uniform.

Catcher Russell “Hack” Ennis played in one major-league baseball game. Though he did not get to bat, he was behind the plate when Ty Cobb got his last hit in a Detroit Tigers uniform.

On September 19, 1926, with his Washington Senators ahead, 7-6, Ennis entered in the bottom of the ninth inning of the final game of a seven-game series at Detroit. It was his seventh day on the team and a prescient Washington Evening Star reported that very morning, ‟[He] may get a chance to show his wares behind the bat during the next week. So far, Hack has done nothing more than warm up pitchers and act as receiver in batting drills, but Boss Bucky [Harris] wants a look at his new catcher under fire.”1

Harris finally utilized his 29-year-old recruit in place of infielder Bobby Reeves, who ran for catcher Bennie Tate in the Senators’ three-run top of the ninth. But Cobb’s pinch-hit RBI single tied the score and the winning run crossed the plate when left fielder Earl McNeely erred on the play.

While Cobb made just one more appearance for Detroit, Ennis watched Washington sweep a four-game series at St. Louis and win one of three games at Chicago to conclude the season. His one-third of an inning in the big leagues landed square in the middle of his career as a professional baseball player.

Russell Edward Ennis was born on March 10, 1897. His parents, Joseph (J.B., 1862-1934) and Victoria (née McDougal, 1864-1927), were married in Dayton, Minnesota, Victoria’s hometown, in 1890. They had seven children, all born in Superior, Wisconsin: Ella (1892-1901), Frank (1894-1968), Raymond (1895-1940), Russell (1897-1949), Vincent (1901-1952), Kathleen Daugherty (1903-1987), and Bernard (1906-1939).

J.B.’s parents immigrated from Ireland with other family members during the Great Famine. They settled in Spring Valley, Wisconsin, near Janesville, to farm.

Born to Irish immigrants in New Brunswick, Canada, Victoria’s mother moved to Minnesota Territory at age 17 in 1856. Victoria’s father, also a Minnesotan born in the Maritimes, died in 1869 from injuries suffered while fighting in the Civil War.

J.B. and Victoria moved to Superior in 1891. Victoria’s sister, Catherine Ann Eichten, and J. B.’s brothers, John and Edward Ennis, also migrated north to the Lake Superior port city, where J. B. was a saloonkeeper and liquor store owner. He also owned racehorses—and ran gambling houses. He and his brothers frequently made headlines for their sensational episodes, including physical altercations, with officials such as the mayor and police chief. Regardless, J. B. became a city alderman.

In 1900, Superior’s semipro baseball team gained a minor-league player from Chicago named Lippert (probably Louis Lippert), who got a job working for the J. B. Ennis Liquor Company.2 In 1902, the Duluth (Minnesota) News Tribune, a newspaper from Superior’s twin port city, reported that J. B. would financially support Superior’s team.

J.B., a Democrat, lost his reelection bid to George B. Hislop, a progressive Republican, in 1903. Hislop, also a baseball supporter, served as the city league’s president. (After Hislop died in 1908 at age 53, a new baseball park for Superior’s minor-league team was built and named in his honor.)

Russell Ennis was known as “Turk” in his hometown but acquired the nickname “Hack” early in his baseball life outside of Superior. No specific support for the origins of these nicknames has surfaced. Yet one may conjecture, because both were used at the time to describe brawny men..

Russell went to the Sacred Heart grade school and may have also attended Superior’s Cathedral High School. He played sandlot baseball in Superior for the Badgers in 1910; the next year, he was the playing manager of his team of 14-year-olds called the A. O. H. (Ancient Order of Hibernians) Cadets. After that, he played for and managed the Holzberg Tailors in 1912, Pease Hardware in 1913, and Superior Box Factory in 1914 and 1915.

As an adult, Ennis stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 160 pounds. He batted and threw right-handed. He played for Washburn, Wisconsin, in the semipro Northwest Interstate League in 1916. Despite its name, the league featured all northern Wisconsin cities that season: Ashland, Hurley, Mellen, Park Falls, Phillips, and Washburn.

Russell played for Superior’s semipro team in 1917 before enlisting in the Army in July. (His brothers Frank and Vincent also served in the Army during World War I.) He sailed for Europe on February 18, 1918, as a wagoner for the Supply Company of the 128th Infantry. He served in France and Germany, attained the rank of sergeant, and returned home in the spring of 1919.

Since the 1920 Superior city directory lists him as a helper at the Globe Shipyards, it’s likely that he’s the Ennis—only last names appeared in newspaper game summaries—who played catcher for the company’s industrial league team in 1919. If so, he caught for former Washington Senators pitcher Carl Cashion as former Cincinnati Reds player Frank Jude manned center field.

There is also a strong probability—again, only last names appeared in print—that Ennis spent the summer of 1920 playing for Flagstaff, Arizona’s town team with future Philadelphia A’s pitcher Buzz Wetzel.3 The Tulsa Oilers signed Ennis in 1921 on the recommendation of Wetzel, who hailed from Jay, Oklahoma.4

Ennis got ample playing time in exhibition games against the Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, Detroit Tigers, Minneapolis Millers, Kansas City Blues, and Enid Harvesters at Tulsa’s McNulty Park. Once the Western League season began, however, player-manager Jimmy Burke went with Wray Query as the first-string catcher. Ennis made his professional debut, and batted 1-for-4, in the sixth game of the season, a 5-4 win at home against the Sioux City Packers on April 20. He played three more games for Tulsa that spring and batted 1-for-15 (.067) before being reassigned.

Ennis made his first appearance for his new team, the Muskogee Mets—managed by Hall of Famer Bobby Wallace—on May 18, 1921, at Coffeyville, Kansas. Some newspapers incorrectly reported the new catcher’s name as Dennis. But later that season, he made a name for himself with an off-the-field incident on a return trip to Coffeyville.

Some Muskogee players, particularly Ennis, had argued with a porter named General Shepard at Coffeyville’s Hotel Mecca before leaving for dinner on the evening of July 31. A fight with Shepard began when Ennis returned to the hotel with teammate John Frese and Muskogee oil promoter Ira Yardley in the early morning of August 1. Ennis received a blow to the head from the butt of a revolver, and two shots were fired. The men were still scuffling when two officers, alerted by the gunshots, arrived from across the street to stop the melee. By then, Frese had possession of the gun as he said he had kicked it away from Shepard.

Shepard, who was black, admitted to drawing the weapon—but said it discharged accidentally—while being attacked by the three men, whom he claimed had called him names. He spent the night in jail and while lynching rumors spread around town, no vigilante action occurred. (Tensions were high in the region at the time. Two months earlier, the Tulsa Race Riot, in which white people destroyed the upscale and predominantly black Greenwood neighborhood, led McNulty Park to be used as an internment camp.)

Shepard posted $25 bond and appeared in court the next afternoon. Neither party claimed ownership of the revolver and there were no reliable witnesses. Thus, the case was dropped on grounds of insufficient evidence. Meanwhile, two bullet holes in the hotel lobby and the gash to Ennis’s head remained. “Booze played its part in the affair, it was said, by several who saw the fight,” reported The Morning News, a Coffeyville newspaper.5 6

Ennis batted .278 in 95 games as Muskogee’s regular catcher in 1921.

The Tulsa World predicted in January of 1922 that “Ennis probably needs another year’s training before he’ll be ready for the Western league.”7 Back in Tulsa that spring, he played in the team’s first two exhibition games—against the Cincinnati Reds—after injuries to the top two catchers. The Oilers hosted the Reds on March 27 and 28. The regular catchers took over after that and the Coffeyville Refiners acquired Ennis on April 12.

Walter Johnson lived in Coffeyville. He served as president of the Walter Johnson Baseball Association, the organization that operated the Refiners. The club faced financial hardship stemming from the 1921 season. According to the Coffeyville Morning News, Johnson, in a speech at an association meeting in January 1922, stated that it did not matter to him personally if Coffeyville had a team, but added that ‟a town that maintains a baseball club … is looked upon as being a worthwhile city. It gives the city distinction.” He also said that the opposite holds true for a city that drops out of a league in midseason.8

The club gave it a go, but the Refiners’ net deficit stood at $3,186.56 on July 1, 1922. A committee formed to address the situation and it was announced on July 5 that $5,027 had been raised in subscriptions. A new board of directors took over and named Ennis as the field manager. He replaced Josh Clarke, brother of Hall of Famer Fred Clarke. “The committee of business men did not hesitate to compliment Josh Clarke for the clean, square, above-board way in which he had managed the team last year and this season, and stated there was no personal feeling connected with the change enacted,” reported the Coffeyville Daily Journal.9

Johnson, reelected as president in absentia and kept abreast of the situation via telegram, wired his eponymous organization on July 8: ‟I am glad you saved the club. Hope everything will be fine. Count on me if I can help you. Best Wishes. Walter Johnson.”10

The Refiners, 2-4 in the second half of the season before the change in management, lost their first game under Ennis on July 5 at Independence, Kansas. They then dropped the initial game of a series at Topeka before notching their first ‟W” for their new manager in the capital city on July 7. They won two more at Topeka and returned home with a 5-6 record.

Coffeyville had an ‟Ennis Day” planned for the home game at Forest Park on July 10, but it was postponed because the opponent, the Sapulpa Yanks, failed to arrive. The Yanks were ‟stranded near Lawrence, due to faulty train service,” according to the Coffeyville Daily Journal.11 Rain then forced postponements on the 11th and 12th. Close to 1,000 fans attended ‟Ennis Day” when it finally went off on July 13. The partisans witnessed a doubleheader split with Sapulpa.

Cleveland manager Tris Speaker invited Refiners players Ike ‟Chief” Kahdot, Ernest ‟Tex” Jeanes, Pat McNulty, and Wayne Middleton to join the big-league club at the conclusion of Coffeyville’s season. Meanwhile, “Russell Ennis, good old Manager Hack, catcher, lives in Superior, Wis., but isn’t very fond of the cold breezes that inhabit the Iron country. He doesn’t have to finish the season with his owners, the Tulsa club of the Western League, and plans on boarding the rattlers for the Pacific coast where he will play winter baseball,” reported Coffeyville’s Morning News.12

The Refiners tied for second place in the second half of the Southwestern League but reluctantly had to look elsewhere for a manager in 1923. The Southwestern League adopted a ‟no farming” rule and Tulsa’s asking price of $1,000 for Ennis’s release was too high for Coffeyville.13 His record as a minor-league manager stands at 38-24 (.613). He batted .281 and led the Refiners with 22 doubles in 1922.

Coffeyville’s annual ‟Walter Johnson Day,” in which Johnson played a game at Forest Park to celebrate his return home each fall, took place on October 8. The Big Train tossed a one-hit shutout as Coffeyville’s ‟All-Stars” beat a collection of semipros from Neodesha, Kansas, 3-0. Ennis was supposed to catch for Johnson, but he and fellow Refiners player George Willigrod didn’t arrive until after midnight. They drove from Willigrod’s hometown of Marshalltown, Iowa, but were overtaken by rain and subsequent muddy roads in Missouri.

While he missed playing with one of baseball’s all-time greats, he got another chance soon enough. Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel barnstormed through the Great Plains later that month. Ennis played on Meusel’s team against the Babe’s squad when their troupe stopped for a game at Bartlesville, Oklahoma, on October 24.

Tulsa posted a 101-65 record in 1923, good for second place behind Oklahoma City (102-64). The Oilers led the Western League in batting (.327) and fielding (.968). All eight regular position players batted well over .300. While Ennis witnessed impressive baseball in ’23, he did not contribute much on the field. Tulsa carried two catchers on their roster, Ennis and Willie Lee ‟Tex” Crosby. Crosby had 760 defensive chances in 160 games compared to Ennis’s 79 in 22 games. Crosby batted .321 in 589 at-bats. Ennis batted .186 in 70 at-bats.

The cancellation of the 1923 ‟Walter Johnson Day” exhibition game in Coffeyville after two rainouts ruined Ennis’s second chance to catch the “Big Train,” for he was scheduled to be Johnson’s receiver once again.14 (A reported 10,000 people turned out for the 1924 event after Johnson led Washington to victory in the World Series. Unfortunately for Ennis, he was 1,500 miles away.)

The St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette reported in December 1923 that Crosby would be back for Tulsa’s 1924 campaign: ‟Tex, of course, will do just about all the catching.” The Gazette also stated that Tulsa had signed Pete Casey, a first baseman and catcher. ‟This acquisition … probably means that Ennis will conduct his baseball business elsewhere next year.”15

Indeed, Ennis spent the summer of 1924 as the regular catcher for the Gilmore Oil Company’s team in Los Angeles. Gilmore lost the Independent League championship game to Shell Oil at Signal Hill on September 28.16

He then served as reserve catcher behind Tubby Spencer for Gilmore Oil’s team in the Southern California Winter League. Spencer had a fingernail torn off from a foul tip while playing against the St. Louis Giants—an all-Black team—at Goodyear Park on December 13, 1924. Ennis finished the game for Spencer and batted 0-for-2 against pitcher (James) Earl Gurley. Future Hall of Famer Cool Papa Bell, playing center field for St. Louis, also batted 0-for-2 but the Giants won, 3-1. Former New York Giants star Ferdie Schupp did the pitching for Gilmore.

Ennis caught the next two games for Schupp, a 7-3 win against the Hollywood Merchants at Hollywood on December 21, and a 1-0 loss at Gilmore Park (at the corner of Fairfax Ave. and 3rd St.) vs. the Pasadena Merchants on December 28. Spencer was back in the lineup at Pasadena on New Year’s Day, 1925. The main athletic event in town that day, the Rose Bowl, featured Ennis’s fellow Superior resident Ernie Nevers playing for Stanford in his legendary performance against Notre Dame.

Ennis parlayed his semipro time into playing for the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League in 1925. He and Tubby Spencer acted as second- and third-string catchers, respectively, behind starter Gus Sandberg. Twenty-three of the 27 Los Angeles players had or would see major-league action. The league featured Tony Lazzeri (who hit 60 home runs) and Lefty O’Doul for Salt Lake City, Lloyd and Paul Waner for San Francisco, and Babe Herman for Seattle. Charlie Root, perhaps Ennis’s most famous Angels teammate, served up Babe Ruth’s ‟called shot” in the 1932 World Series.

The Angels, owned by chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley Jr., moved from Washington Park to Los Angeles’s Wrigley Field toward the end of the season. Ennis didn’t get to play when the park opened on September 29, but he later caught the first game of a doubleheader before 10,000 fans at the new stadium on October 4.

Spencer, in his last season, had the highest batting average (.275) but the fewest at-bats (109) among the three catchers. Ennis batted .238 in 181 at-bats and Sandberg hit .231 in 471 at-bats.

The Angels sold Ennis to the Beaumont (Texas) Exporters in February of 1926 after signing veteran catcher Truck Hannah to back up Sandberg.

Ennis played spring training games for Beaumont but was in an Elmira (New York) Colonels uniform by April 25 in an exhibition game against Albany. Manager Joe Dunn released Bob Hyde, Elmira’s starting catcher in 1925, after the first game of the New York-Pennsylvania League season to make way for Ennis.17 Hyde had been Ennis’s reserve catcher for Coffeyville in 1922.

On September 12, 1926, Ennis received a $50 strap watch for being named Elmira’s MVP before the final game of the season in which he batted .262 and led the team with 11 triples. He joined Washington at Cleveland the next day.

The Senators found difficulty in replacing third-string catcher Hank Severeid after selling him to the Yankees in July. They had Jimmy Smith, whom the Evening Star called ‟[a] young sandlot catcher from Salem, Ohio,” for a few days before buying the services of Hilton Brandon from Portsmouth of the Virginia League on September 2.18 But on September 8, they obtained Ennis and sent Brandon packing. (The initial transaction worked out much better on the other end. Severeid started all seven games of the 1926 World Series.)

Walter Johnson factored into Ennis’s lone major-league appearance when he uncharacteristically blew a 2-1 lead by allowing five runs in the sixth inning at Detroit. Various substitutions resulted in starting catcher Muddy Ruel’s removal and Harris’s subsequent need for a third catcher after the rally in the top of the ninth.

Ernie Nevers made his NFL debut on the same day as Ennis’s major-league baseball debut. Nevers’s Eskimos, representing Duluth, played their lone home game of the season that day. Nevers had been a rookie pitcher for the St. Louis Browns that year. The two Superior athletes would’ve met in St. Louis had Nevers not left early to join the Eskimos in Two Harbors, Minnesota, for the first training camp in NFL history.

The Elmira Star-Gazette of February 1, 1927, reported that Ennis would be back with the Colonels for the upcoming season. It noted that he had two appearances for Washington: one as a catcher and one as a pinch-hitter.19 References do not show the pinch-hitting role, nor has further research for this story revealed it.

Upon hearing of his mother’s death on August 11, 1927, Ennis left Elmira to attend the funeral in Superior. Mrs. Ennis had been an invalid for 17 years.

He batted .279 and led Elmira with five home runs as the Colonels’ top backstop in ’27. His achievements led to another promotion to a team named the Senators: the Columbus (Ohio) Senators of the American Association. While he had two hits in a game against Indianapolis at Columbus on September 8, he was replaced in the eighth inning of a 12-3 loss after allowing two passed balls. The Indianapolis News noted that he ‟has failed to impress.”20 Columbus, which had future Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell, sent him back to Elmira later that month.

When Ennis reported for duty in 1928, the Star-Gazette noted that he ‟looked fine and fit after a winter on the bowling alleys.”21 He enjoyed another season as the Colonels’ starting catcher and batted .267 in 281 at-bats (reserve catcher Norbert ‟Doc” Niederkorn batted .317 in 167 at bats) for manager Jack Sheehan.

In 1929, the Colonels did not have a suitable second-string catcher to relieve Ennis. He batted .351 through June 22 but played nearly every game until sidelined by a shoulder injury.22 Manager Jake Pitler tried Al Lesko, Gus Dundon, and James “Wickey” McAvoy as replacements. Ennis returned, but his average dipped to .287 for the season. Pitler placed him on the suspended list with no public explanation on August 1, 1929, the day after signing veteran catcher Joe Jenkins.

Four days later, in the early hours of August 5, a car accident put Ennis in Elmira’s St. Joseph’s Hospital with “a severe scalp laceration and body bruises,” according to the Elmira Star-Gazette.23 Ennis was a passenger in a car driven by a local salesman, Duane Ruckman, when Ruckman’s vehicle collided with one driven by Stanley Gublo. Both drivers were arrested: Ruckman for drunken driving and Gublo for driving without a license.

Jenkins finished the year as the mainstay behind the dish. He batted .330 in 35 games.

Pitler told the Elmira Star-Gazette in December of ’29 that Ennis ‟… would never again appear in a Colonel uniform … I am trying to trade or sell him but if my efforts fail, I will give him his outright release. He is not going to be on my ball club next year. “24

Jenkins batted .320 in 1930 as Elmira’s catcher. Ennis was out of Organized Baseball.

The Bloomington (Illinois) Cubs of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League hired Joe Dunn as manager in 1931. Dunn signed Ennis to bolster his catching corps, which included former Oregon State star quarterback Howard Maple. Ennis batted .333 in 14 games but was released in June because of injuries that plagued his brief time in the Three-I League. Veteran minor-leaguer Walter Dunham took his place as Maple’s backup.25

Ennis returned to Superior after his baseball career to follow in his father’s footsteps. On April 28, 1932, he was fined $150 and sentenced to two months in a house of correction on a Prohibition law violation.26

With the end of Prohibition in 1933 and J. B.’s death in 1934, Ennis took ownership of the Garden Tavern at 1924 Belknap Street, the same location where J. B. had a bar. He even lived in his childhood home next door.

In 1938, a Garden Tavern bartender named David Kitter died after being struck by a car outside the tavern. Kitter joined a crowd gathered to observe the aftermath of a collision at the base of a viaduct’s slippery slope. When another car came down the viaduct, the driver lost control after trying to avoid the cluster of people and the car fell off the curb and onto Kitter and other bystanders.27

In 1942, Ennis married Cozette “Cozy” Kitter, David’s sister, on October 20 at Carlton, Minnesota. He enlisted in the Army at Milwaukee on November 10. He served with the 3rd Battalion of the 52nd Armored Infantry Division and received an honorable discharge on February 4, 1943.

Ennis moved to Cozy’s residence, the extant Rose Hotel at 1715 Winter St., which she and her mother had purchased in 1936.

The city council revoked Ennis’s liquor license for serving minors in a special meeting on June 16, 1947, three days after a man was murdered in nearby Lake Nebagamon, Wisconsin. One of Ennis’s bartenders served and sold whiskey to the three youths involved in the foul play.

Ennis died at age 51 at St. Mary’s Hospital in Superior on January 21, 1949, from a cerebral hemorrhage resulting from hypertension. He is buried in the family plot at Calvary Cemetery in Superior.

Cozy, born in Superior in 1900, continued to operate the Rose Hotel into the 1960s. Her son, Ennis’s stepson, James “Noonie” Kitter, died in 1968. Cozy died in 1981 and is buried at Superior’s St. Francis Cemetery alongside her brother and son.

The Garden, later the Viaduct bar, along with the old Ennis home, was demolished when the actual viaduct was replaced in the early 1980s. Its spirit lives on, however —the site is now the location of the Keyport Liquor Store, Restaurant, and Lounge.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Ashley McDonald, Teddie Meronek, and David Ouse for research assistance, and Brenda Glonek, Russell Ennis’s great granddaughter, for correspondence via Facebook Messenger. This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Superior Telegram and the following:

Ancestry.com

Findagrave.com

Genealogybank.com

https://moms.mn.gov

Newspapers.com

Baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Russell Ennis.

Douglas County Historical Society

Douglas County Register of Deeds office

Duluth Public Library

Superior Public Library

Notes

1 “Johnson to Pitch Today in Final Against Tygers,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), September 19, 1926, p.76.

2 “New Ball Tosser,” Duluth News Tribune (Duluth, Minnesota), May 4, 1900, p. 5.

3 “Additional Local Items,” Coconino Sun (Flagstaff, Arizona), July 23, 1920, p. 5. (A pitcher named Wetzel and a catcher named Ennis appear in game coverage; no first names are reported.)

4 “Tulsa Oilers Start Spring Training Here Tomorrow,” Tulsa Daily World (Tulsa, Oklahoma), March 13, 1921, p. 10.

5 “Fight with a Gun Play Staged at a Local Hotel at an Early Hour M’day,” Morning News (Coffeyville, Kansas), August 2, 1921, p. 5.

6 “Hotel Porter and Visiting Baseball Player in Trouble,” Coffeyville Daily Journal (Coffeyville, Kansas), August 1, 1921, p. 2.

7 B.A. Bridgewater, “Oilers Purchase Thirdbaseman [sic] and Pitcher from American Association Clubs,” Tulsa World, January 29, 1922, p. 12.

8 “Baseball in Coffeyville is Pending,” Morning News, January 21, 1922, p. 1.

9 “Hack Ennis is Manager,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, July 5, 1922, p. 1.

10 “Ennis Day Monday,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, July 8, 1922, p. 8.

11 ‟Postpone ‛Ennis Day,’” Coffeyville Daily Journal, July 10, 1922, p. 8.

12 “End of Southwestern League Season Sends Coffeyville Players to All Parts of Country; Three Games Left,” Morning News, September 3, 1922, p. 3.

13 ‟Refiners Heads Still Debating on New Manager for ’23 Season,” Morning News, January 11, 1923, p. 3.

14 “Scheming Way to Pay Off Refiner Players,” Daily Free Press (Independence, Kansas), October 17, 1923, p. 6.

15 “Oilers Look Good for 1924 Season,” St. Joseph Gazette (St. Joseph, Missouri), December 27, 1923, p. 3.

16 “Title Goes to Shell Oilers,” Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1924, p. 10.

17 “Hyde Released by Colonels,” Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), May 8, 1926, p. 8.

18 “Nats Purchase Catcher Brandon of Portsmouth,” Evening Star, September 2, 1926, p. 38.

19 “Hack Ennis Will Join Colonels for Campaign of Coming Season,” Star-Gazette, February 1, 1927, p. 9.

20 “Indians Clout and Beat Poor Senators,” Indianapolis News, September 9, 1927, p. 34.

21 “Fans Welcome Jack Sheehan; Ennis Reports,” Star-Gazette, April 14, 1928, p. 8.

22 “Pitler Signs Lesko to Give Ennis Relief,” Star-Gazette, June 5, 1929, p. 15.

23 “Elmira Ballplayer Injured, Two Drivers Are Arrested Result of Motor Accident,” Star-Gazette, August 5, 1929, p. 2.

24 “Jake Pitler Building Team for 1930 League Race; Stops Here on Way to Home,” Star-Gazette, December 23, 1929, p. 11.

25 R.A. Drysdale, “The Dope Bucket,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), June 13, 1931, p. 10.

26 “Eau Claire Men Are Sentenced,” Chippewa Herald-Telegram (Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin), April 28, 1932, p. 3.

27 https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5914cbe3add7b049348060d0.

Full Name

Russell Edward Ennis

Born

March 10, 1897 at Superior, WI (USA)

Died

January 21, 1949 at Superior, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.