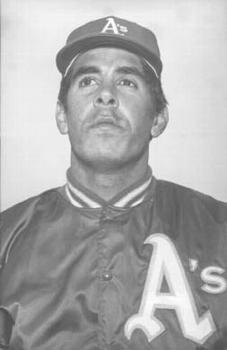

Roberto Rodriguez

When danger arose and duty called, mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent would duck into a telephone booth to change into Superman. The typically phlegmatic Dr. Bruce Banner, if sufficiently provoked, would struggle not to unleash his alter ego, the Incredible Hulk. The metamorphosis of Venezuelan pitcher Roberto Muñoz was far less dramatic and indefinitely less colorful; crossing the United States border would change him into Roberto Rodríguez. Hispanic culture anoints children with the surnames of both parents; in his case, Muñoz was his paternal last name and Rodríguez his mother’s. Much like Puerto Rican star Víctor Pellot Pove (a/k/a Vic Power) and Dominican legend Felipe Rojas Alou, generations of fans would know the Venezuelan pitcher by a truncated name. (This biography uses the anglicized version, Roberto Rodríguez, since it was one used in major-league baseball.)

When danger arose and duty called, mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent would duck into a telephone booth to change into Superman. The typically phlegmatic Dr. Bruce Banner, if sufficiently provoked, would struggle not to unleash his alter ego, the Incredible Hulk. The metamorphosis of Venezuelan pitcher Roberto Muñoz was far less dramatic and indefinitely less colorful; crossing the United States border would change him into Roberto Rodríguez. Hispanic culture anoints children with the surnames of both parents; in his case, Muñoz was his paternal last name and Rodríguez his mother’s. Much like Puerto Rican star Víctor Pellot Pove (a/k/a Vic Power) and Dominican legend Felipe Rojas Alou, generations of fans would know the Venezuelan pitcher by a truncated name. (This biography uses the anglicized version, Roberto Rodríguez, since it was one used in major-league baseball.)

Roberto was born on February 5, 1941, in the capital city of Caracas to Juan Muñoz, who would work for 44 years at the local brewing company Cervecería Caracas, and Julia Rodríguez, who stayed at home with the children. They were of humble socioeconomic status; Roberto shined shoes and delivered newspapers to aid the family budget and liked to play baseball whenever he could. His uncles, both semiprofessional players, infected him with the bug.

Former minor leaguer Tony Pacheco discovered him as a catcher. Signed by the Kansas City Athletics one day shy of his 22nd birthday, Rodríguez reported to the Florida State League in the spring of 1963. He appeared in 38 games for Class-A Daytona Beach and fielded well (241 chances, 218 putouts, 19 assists, four errors, three double plays, and 11 passed balls), but his offensive contribution was anemic (20 singles and three extra-base hits in 133 at-bats).

His demeanor was chipper: “I was always in good spirits, so when I wasn’t catching the game, I could throw batting practice.”1 A Kansas City scout, Bill Posedel, saw something in the young right-hander and asked Rodríguez to come early the next day for an experiment. “First, I threw four fastballs and then a slider. … They told me there was no reason to keep throwing, and from that moment they ordered me to switch the mitt for the pitcher’s glove.”2 He would spend the rest of the season working on his pitching.

Assigned to the Class-A Midwest League in 1964, Rodríguez pitched in 24 games, earning 11 victories against eight defeats on the strength of a 3.35 ERA for the Burlington Bees. He also appeared in four contests in the Class-A Northwest League, tossing four innings and allowing five earned runs for the Lewiston Broncs. He returned to Lewiston in 1965 and delivered a robust 3.97 ERA over 136 innings (13-4, two saves) to earn a promotion to the top farm club, Vancouver of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. His 1966 record (seven wins, seven losses) belied strong fundamentals, including only nine home runs allowed and a 2.55 ERA over 148 innings. He was even more impressive in 1967, improving to 12-4 while lowering his WHIP to 1.047 and receiving the much-desired call-up.

Rodríguez broke into the American League with the Athletics, who were subjecting Kansas City to one last losing season before departing for Oakland. A pair of 21-year-old prospects would blossom into Hall of Famers, as Reggie Jackson and Catfish Hunter would be the nucleus of the early 1970s three-peating Athletics, but their early exploits were inconsistent. Rodríguez became the third Venezuelan-born player to pitch in the majors after Alex Carrasquel and Ramón Monzant, upon his debut on May 13 at Minnesota, hurling 1⅓ innings without allowing a run to earn a hold.3

The A’s lost his next three appearances, with Rodríguez allowing four runs to close out May with a 5.14 ERA. The team sent him back to the minors before recalling him for the stretch run. He was stingy in August, pitching 14⅔ innings and allowing only two runs; he picked up his first save on August 19 as the Athletics beat the Senators, and his second one a few days later in Baltimore. To close the month, the franchise gave Rodríguez the opportunity to start, and he took full advantage of it, scattering four hits over 6⅓ innings to beat Detroit. Future Hall of Famers Eddie Mathews and Al Kaline failed to get a hit in six at-bats, though the latter reached base on a fielder’s choice. Rodríguez’s fortunes turned in September, as 12 men crossed the plate against him in 18⅔ innings, including his first loss, also at Minnesota. As the season ended and the franchise packed its bags for California, Rodríguez could be forgiven for thinking he would follow suit, but the front office returned him to Vancouver for more development. Topps was also fooled, giving him card number 199 (alongside Darrell Osteen, “Athletics Rookie Stars”) in the 1968 set, fully expecting him to be part of the Athletics’ season.

Back in the minors and given 28 starts, Rodríguez generated 23 decisions (12 wins, 11 losses) but his peripherals worsened; his ERA jumped to 4.20 and his WHIP to 1.356 as the Mounties finished last in the league in 1968. That season was a turning point for the PCL; it would shrink from 12 franchises to eight after San Diego and Seattle were granted expansion major-league franchises to begin playing in 1969, making minor-league ball in those cities financially challenging. In preparation, Oakland moved its affiliation to the American Association, resurrected after a seven-year hiatus. The Iowa Oaks were consistent; they finished fourth in the standings, fourth in runs per game scored, and third in most runs allowed in the 1969 season. Rodríguez struggled, tossing 130 innings between the starting rotation and the relief corps; he ended the season with five wins, eight losses, and four saves on a 4.92 ERA and 1.608 WHIP.

Rodríguez began the 1970 season with Iowa but appeared in only two games (three innings, two hits, three strikeouts) before making his way back to the majors, rejoining his Athletics teammates. He was not frequently used, appearing in only six of the team’s first 35 games. He provided a solid 2.92 ERA in 12⅓ relief innings, as Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, and Vida Blue led a strong, yet still young, starting rotation. The franchise sold his contract to San Diego but he played in only 10 games with the Padres before being sent to the Chicago Cubs for cash considerations. Going from an expansion team to one of the National League’s oldest franchises was a new experience. Rodríguez’s third team in one year – all in different divisions – gave him meaningful contests late in the season and he shared the clubhouse with four eventual Cooperstown legends (Ron Santo, Billy Williams, Ernie Banks, and Fergie Jenkins). Through his last 26 major-league games, Rodríguez enjoyed successes (three wins, two saves) and tasted bitter defeats (two losses, one blown save). After the historical collapse of the 1969 Cubs, the 1970 edition led their division through the summer but yielded the crown to the Pirates, finishing in second place with an 84-78 record.

Rodríguez’s three most memorable games in a Chicago uniform involved Bill Hands. The Venezuelan proved his mettle by inheriting a bases-loaded situation from Hands in the top of the ninth inning with no outs against Montréal on July 6. He struck out John Bateman and Coco Laboy before getting Bob Bailey to ground out to shortstop to finish the game and earn the save. On July 26 the Cubs hosted a doubleheader against Atlanta. They fell behind early in the opener, as starter Hands was manhandled by Orlando Cepeda (three home runs in as many at-bats, including a grand slam) to bring Rodríguez into the game. Chicago manager Leo Durocher would have preferred to wait until the fifth inning to change his hurler, as the pitcher’s spot was up first in the next frame, but his starter’s struggles left him no choice. Having inherited runner Tony González, Rodríguez walked Mike Lum before retiring Clete Boyer.

Rodríguez had barely taken off his glove before he was summoned to the plate. Perhaps he was in a hurry to return to the dugout to discuss how to approach the next few hitters; maybe he just saw a pitch he liked and did what any hitter seeks to do. The throw from Pat Jarvis disappeared not just over the fence, but out of the park, as Rodríguez attained his first and only career hit with a four-bagger. Through the 2019 season, 1,306 retired players have enjoyed only one hit in the majors.4 Of those, only 19 (1.45 percent) have done so with a round-tripper, making it a remarkable accomplishment.5 Rodríguez had never hit a home run in the minor leagues or during Venezuelan competition. In a television interview, he was humble about the accomplishment: “That was by chance. Jarvis was not bad, he had won 16 games in a season. Maybe he thought, ‘This is the pitcher, I’ll just throw something by him.’ I thought, ‘The first one I like, I’ll swing.’ I think it took me half an hour to circle the bases!”6

Rodríguez remained on the mound and stopped the bleeding by keeping all 10 hitters he faced from crossing the plate; however, the team needed more runs so Durocher lifted him for Al Spangler in the seventh inning. The Cubs lost the contest, 8-3, but won the second half of the doubleheader, with Rodríguez picking up his fifth save. He won a pair of games and lost another, with his last major-league appearance occurring on September 26. Chicago dropped its 157th game to Philadelphia, 7-1, with Hands once again getting an early hook (six runs in 1⅔ innings). Juan Pizarro provided 2⅓ scoreless frames before turning over the ball to Rodríguez, who faced 10 batters, striking out one, walking another, and allowing two hits; a double play and a runner caught stealing kept the Phillies from scoring again during his three innings.

In 1971 Rodríguez returned to the PCL as a member of the Tacoma Cubs, providing a veteran presence, starting 26 games (completing 11), relieving in five others, and posting a 4.01 ERA in a career-high 204 innings. Chicago switched its Triple-A affiliation in 1972, to Wichita. Rodríguez would play three full seasons (1972-1974) in with the American Association’s Aeros, tossing 308 total innings for a 19-15 record with 16 saves.

Rodríguez’s major-league numbers (4.81 ERA, four wins, three losses, seven saves in 57 games, five of which were starts) have long been eclipsed by his fellow Venezuelan pitchers. His sole hit was memorable, though he also reached base one other time in his career, in 1967 against Baltimore on an error, later scoring on a Bert Campaneris triple. He started the game but did not get the decision as he was lifted after 4⅓ innings.

Though his major-league career was brief, Rodríguez’s foray in the Venezuelan winter league was legendary. Appearing in the box score as Roberto Muñoz, he played for multiple franchises from 1961 through 1979 (except for 1962-1963). He won the championship with the Tigres in 1971-1972, 1974-1975, and 1975-1976 (though he did not take the mound in the championship series). He won the finals MVP award in 1971-1972, appearing in six games, winning two and saving one and yielding only three runs in 16⅔ frames. He appeared in four other championship series: with the Valencia Industriales (1965-1966 and 1967-1968), the Tiburones (Sharks) of La Guaira (1966-1967), and the Navegantes (Navigators) of Magallanes (1968-1969).

Rodríguez was the first hurler to record 50 career victories and an equal number of saves in the Venezuelan league. Throughout this career, he led the league in ERA, strikeouts, innings pitched, complete games, and saves on various occasions.7 With Aragua he earned the “Iron Horse” nickname as he was seemingly always relieving the team’s starters. His 64-49 record, with 59 saves and a 3.04 ERA, was amassed in 267 relief appearances (second place all-time) and 1,228⅔ innings (fifth place all-time). He also ranks fifth in strikeouts with 734. During the semifinals (first round of postseason) he forged a 3-3 tally with four saves in 60⅓ frames, with an additional 7-6 mark and one save in the finals.

Rodríguez’s contemporary, Nelson Castellanos, gave him the sobriquet “Pluto,” though years afterward, Rodríguez was vague as to why: “Maybe because he thought I was aloof, though I picked off a lot of men on base. … Maybe because I’d walk around the pitcher’s mound before throwing to home plate.”8 He cherished a friendly rivalry with Isaías “El Látigo” (The whip) Chávez, whose career was cut tragically short in a 1969 plane crash that claimed all 84 passengers and 70 people on the ground.9 They faced off twice in 1967-1968, each one winning a contest by the slimmest of margins, 1-0.10

In one of his best anecdotes, Rodríguez recalled swinging wildly at a pitch while Adolfo Phillips stole home; Caracas pitcher Diego Seguí retaliated by hitting him in the elbow, causing him to be taken out. Caracas then rallied to win the game and the Venezuelan title. “Later that year, while playing minor-league ball, Seguí and I faced each other. I drilled him in the head, and then visited him in the hospital. He told me, ‘Venezuelan, as soon as I get out of here I’m going to get even.’ I answered, ‘Cuban, you beaned me there, I got you back here. Now we’re even.’”11 The two would be teammates in the minors (Vancouver, 1967), the majors (Kansas City, 1967, Oakland, 1970), and the Venezuelan league (Caracas, 1978-1979).

Rodríguez’s post-playing career was bittersweet. He worked at a car dealership and at a Maracay baseball academy owned by former big leaguer Carlos Guillén. A falling-out with the Aragua ownership strained ties with the ballclub. Although the franchise was in other hands, he confessed in a television interview not to have attended a game in many years, though he would “be proud to throw a first pitch” if he were invited.12 He had sued Aragua for 190,000 bolívares and won the lawsuit; as a result, he felt he was blackballed not just from a job in the winter league, but also from the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame. The slight originated from the 1972 Caribbean Series, when Rodríguez felt the players were ill-treated by management. He was particularly incensed at the suggestion of a club official that players’ wives should pay for their own travel. “I said, ‘Well, then you put on the uniform, pick up the glove, and go pitch, because I won’t.’”13 Ownership acquiesced, claiming it was a misunderstanding, and Rodríguez played in the series (in the Dominican Republic), “but the damage was done.”14 Team Puerto Rico won the series but was handed its only defeat by Venezuela. Rodríguez appeared in five games, saving three, and being named to the all-tournament team.15 He struggled in the 1975 edition, dropping two games against the Dominican Republic.

Married to Carmen since 1963, Rodríguez had three sons, the eldest of whom died in 1995 from cardiac arrest. His nephew, Nelson Torres, followed his footsteps to the pitching mound. In a dozen years in the Venezuelan league, he appeared in 104 games, going 10-10 while picking up six saves.16

In addition to his 368 Venezuelan winter league games, Rodríguez also appeared in one season in the Mexican league (14 games, 2-4, two saves).17 He was elected to the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame on September 13, 2011, with his plaque dedicated the following year.18 “I wasn’t expecting to be elected. … This has great meaning for me. To be considered and to go in with such stars is a great honor.”19 He died of a heart attack on September 23, 2012, in Maracay and is buried in the Cementerio Metropolitano de Aragua. His uniform number was belatedly retired by Aragua in 2015 during a pregame ceremony attended by his widow, two surviving children, and grandchildren.20

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted game information on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Los Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas,” May 20, 2012. grandesligasve.blogspot.com/.

2 “Los Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas.”

3 Though the “hold” statistic was not official until the 1980s, they have been retroactively awarded to pitchers. For more information, consult MLB.com’s glossary: m.mlb.com/glossary/standard-stats/hold.

4 Baseball-Reference search query: one career hit, retired players as of September 7, 2019. baseball-reference.com/tiny/oI6p1.

5 Baseball-Reference search query: one career hit, one career home run, retired players as of September 7, 2019. baseball-reference.com/tiny/bdsW0.

6 La Voz del Fanático television show, hosted by Ramón Corro. Meridiano Televisa, 2007 original broadcast. youtube.com/watch?v=z9BYzrbU0rw.

7 pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=munorob001.

8 Alfonso L. Tusa, “Pluto y el Caballo de Hierro,” Magallaneando Blog, September 24, 2012. magallanenando.blogspot.com/2012/09/pluto-y-el-caballo-de-hierro-los.html.

9 Kevin Czerwinski, “El Latigo Left Legacy in a Career Cut Short,” MiLB.com, March 26, 2008. milb.com/milb/news/el-latigo-left-legacy-in-a-career-cut-short/c-365649.

10 Tusa.

11 Tusa.

12 “La Voz del Fanático.”

13 “La Voz del Fanático.”

14 “La Voz del Fanático.”

15 Miguel Dupoy Gómez, “Béisbol Inmortal: Roberto Muñoz, el ‘Caballo de Hierro’ Venezolano,” September 1, 2016. beisbolinmortal.blogspot.com/2016/09/roberto-munoz-el-caballo-de-hierro.html.

16 pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=torrnel001.

17 “Wilson Alvárez, Luis Salazar, Oswaldo Guillén y Roberto Muñoz exaltados al Salón de la Fama 2011,” September 13, 2011. valenciainforma.obolog.es/wilson-alvarez-luis-salazar-oswaldo-guillen-roberto-munoz-exaltados-al-salon-fama-2011-13-9-2011-1274738.

18 museodebeisbol.com./salon_fama_venezolano/get/2011.

19 Ignacio Serrano, “Se fué un inmortal, el gran Roberto Muñoz,” El Emergente, September 24, 2012, elemergente.com/2012/09/se-fue-un-inmortal-el-gran-roberto-munoz.html.

20 “Retiran el número 20 con que jugó; Roberto ‘Pluto’ Muñoz será homenajeado este domingo en Aragua,” Correo del Orinoco, December 13, 2015. correodelorinoco.gob.ve/roberto-pluto-munoz-sera-homenajeado-este-domingo-aragua/.

Full Name

Roberto Rodriguez Munoz

Born

February 5, 1941 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

Died

September 23, 2012 at Maracay, Aragua (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.