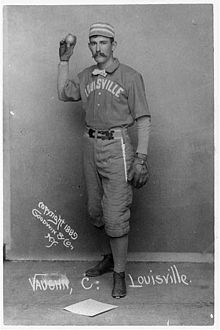

Farmer Vaughn

Farmer Vaughn was “a strapping big fellow,”1 standing 6-foot-3 and in his prime weighing in at 180 pounds. Outspoken and fun-loving, he was also highly competitive and, at times, combative. He drew quite a few fines over the years for arguing with umpires both as a player and as a manager. While guiding his 1906 Birmingham Barons to the Southern League title, he had an unusual number of run-ins with authority. On the final day of the season, just as the game was to begin, umpire Frank Rudderham held up the ball supplied by Birmingham and said, “This looks bad to me … I will have to report it to President (William) Kavanaugh.” Vaughn was visibly shaken but before he could stammer an explanation the umpire produced a gold Elks watch fob and presented it to him on behalf of the players.2

Farmer Vaughn was “a strapping big fellow,”1 standing 6-foot-3 and in his prime weighing in at 180 pounds. Outspoken and fun-loving, he was also highly competitive and, at times, combative. He drew quite a few fines over the years for arguing with umpires both as a player and as a manager. While guiding his 1906 Birmingham Barons to the Southern League title, he had an unusual number of run-ins with authority. On the final day of the season, just as the game was to begin, umpire Frank Rudderham held up the ball supplied by Birmingham and said, “This looks bad to me … I will have to report it to President (William) Kavanaugh.” Vaughn was visibly shaken but before he could stammer an explanation the umpire produced a gold Elks watch fob and presented it to him on behalf of the players.2

The surprise presentation was one of the few times Vaughn was left speechless. He was not afraid to speak his mind over the years on any number of subjects. He said he was ashamed to play for a last-place Louisville club.3 He complained that a passion for “small ball” that found sluggers like Dan Brouthers bunting “made life miserable for catchers.”4 He objected to players being forced to umpire: “There is everything to lose and nothing to gain.”5 He was at his best spinning tales from the diamond—like the time the opposing pitcher “was wearing a long, anarchistic looking beard.” A grounder bounced up and stuck in the whiskers which forced the pitcher to chase a runner and touch him with his chin whiskers. Vaughn closed the story by saying “the umpire called him out by a hair.”6

Henry Francis Vaughn—known as “Harry” and “Farmer”—was born March 1, 1864 in Ruraldale, Ohio. His father, Francis M. “Frank” Vaughn, was a laborer who moved the family from east of Columbus to Clermont County, east of Cincinnati, before the 1870 census. Harry’s mother was the former Zerrelda7 Batters. Harry was the third child, joining two older sisters. A brother and four more sisters would join the family later.

Harry attended enough school to become literate and then joined the workforce, mainly as a farmhand. He played baseball and eventually moved into the semipro ranks as a catcher. In 1886 he was playing with a team from Lebanon, Ohio, when the Cincinnati Red Stockings in the American Association spotted him. He was invited for a tryout and on October 7, he was paired with rookie pitcher Bill Irwin, making his second start for the team, in a match against the Metropolitans. Irwin allowed six runs in the first before he settled down, eventually losing, 8-4. Vaughn went hitless at the plate. In the field he handled 12 chances with an error. He also committed two passed balls. The Red Stockings chose not to retain Vaughn.

The New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern League relied heavily on talent from the Cincinnati area. Pitchers John Ewing and Wild Bill Widner were on the team, as were the Fuller brothers, Shorty and Harry. Whether these players suggested Vaughn to Pelicans management or he was already known to them is unclear. Whatever the case, Vaughn went south in 1887 to play for the Pelicans.

The Pelicans opened the season with two wins over Mobile before Vaughn was given his first work on April 19, catching for William Rittenhouse. Rittenhouse surrendered 13 hits and four runs. Vaughn appeared “a little awkward … held on to everything behind the bat and did not make a single wild throw, retiring thee men at second.”8 The Pels won, 13-4, and Vaughn had two hits, scored twice, and stole a base.

The team carried three catchers who also played outfield and/or first base. Vaughn caught 46 games and played outfield in 20 others. He posted a .296 batting average and poked a home run. New Orleans held onto first place until mid-September when Charleston surged into the lead. The Pelicans hosted the Quakers in a four-game series and regained the lead. New Orleans went on to capture the title by seven games over Memphis.

The following season John Ewing and Vaughn abandoned New Orleans and signed with the Memphis Grays. Ewing paired with Kid Nichols to give Memphis two excellent hurlers. Vaughn split the catching duties, but injuries limited him to 18 games.

In mid-July Memphis released Ewing and Vaughn. They quickly signed with the Louisville Colonels in the American Association. Both men struggled with the major-league club. Ewing won eight of 21 starts. Vaughn regained his health and played 53 games. His fielding was not sharp, he committed 28 errors and 23 passed balls. His hitting was a dismal .196 for the seventh-place club.

Both men returned to Louisville for the 1889 season as Vaughn played catcher, outfield, and first base. He spilt the backstop duties with Paul Cook. Between the two of them, they batted a combined .234 and committed a whopping 137 passed balls. Ewing posted a record of 6-30 for the cellar dwellers.

On December 3, Harry wed Gertrude Norris at her home in Rock Spring, Kentucky. The couple lived in Louisville for a short while before heading to the Savannah, Georgia area. They wintered there before joining the New York Giants of the Players’ League for spring training. Vaughn had not resigned with Louisville because of his interest in the Players’ Brotherhood both politically and financially. Buck Ewing was the team manager and John Ewing joined the pitching staff.

Long-distance baseball throwing contests were in vogue at that time. Vaughn lost out on a $100 prize in 1888, and in 1889, Vaughn recorded a toss of nearly 123 yards but lost the contest. In 1890 in a contest in Buffalo, Vaughn got off a heave of 134 yards, 2 feet, 2 inches,9 earning $25 for his efforts.

Vaughn served as the third-string catcher for the Giants. Buck Ewing was number one and William Brown caught four more games than Vaughn. Both backups saw utility duty during the season. When the season ended, and the league disbanded, Vaughn’s rights reverted to Louisville. In December, newspapers started to report/speculate that Vaughn would instead play for Cincinnati’s American Association team and King Kelly.

Meanwhile Vaughn was farming in Rock Spring, Kentucky. He brought a load of tobacco to Cincinnati to sell in December 1890.10 The nickname “Farmer” was sparsely used in reference to him before this sales trip. Manager King Kelly referred to him as “Farmer” once training camp got underway and the nickname stuck.

As spring training approached, Louisville was offering Vaughn to other teams. He signed with Cincinnati in early March, but terms of his release from Louisville are unknown. Kelly’s team was a new entry into the Cincinnati market. The National League had taken the best players from the last Association entry and were clearly the fan favorites.

After weeks of speculation, the end was drawing close for Kelly’s Killers. On August 15, the Association team left for St. Louis. In a unique twist, Kelly’s Killers played St. Louis on Saturday and Sunday. The franchise then disbanded and on Tuesday the new Milwaukee franchise played St. Louis.

The Milwaukee Brewers team was made of players from the Western Association Milwaukee Brewers and members of the defunct Cincinnati team. Jack Carney and Jim Canavan from Cincinnati played the first game for the AA Brewers. Vaughn and two pitchers also made the switch from Cincinnati to Milwaukee. Vaughn played 51 games for Cincinnati and 25 for Milwaukee, batting .285.

Charles Comiskey took over as manager for the National League Cincinnati Reds in 1892. He brought in Morgan Murphy and Vaughn from the defunct American Association and pushed the incumbent catcher, Jerry Harrington, to the end of the bench. Murphy was the most consistent of the catching trio, but Vaughn had by far the best arm and bat. Murphy hit only .197 while Vaughn hit .254, fourth on the team for players with 100 or more at-bats.

Vaughn’s breakout season came in 1893. At the age of 29 and in his prime, he seized the number-one catching spot and played 80 games behind the dish, as well as seeing action at first and in the outfield. He batted .280 and led the team with 108 RBIs. Not bad for a player who was not considered a starter in the preseason. Comiskey, when asked about Murphy’s holdout said, “We still have the old reliable farmer, Harry Vaughn, to fall back on.”11 Far from a ringing endorsement of his value.

Vaughn captured the starting spot and fit into the fifth spot in the Cincinnati batting order. There was a fear in May that he would be suspended after an incident with Steve Brodie and the St. Louis Browns. In the fifth inning of the May 15 game in St. Louis, Brodie attempted to score from second on a base hit to center. Brodie and the ball arrived at the same time and the collision jarred the ball from Vaughn’s mitt. Vaughn then reached for a bat and threw it at Brodie. The Browns surrounded Vaughn, who was quickly fined $25 and ejected from the game.12

President Chris Von der Ahe of the Browns employed a bit of gamesmanship and had Vaughn arrested for assault before he could leave his hotel the next day. This forced Murphy into the lineup again. The Reds won, 9-6, despite Murphy going hitless. Vaughn returned to the lineup the next day after bond was posted.13 The Reds won, 3-1.

The collision and its aftermath were played out in the Sporting Life. Writers from each city put their spin on the events. The Cincinnati position was that Brodie was a dirty player who threw a fist into Vaughn’s ear. They also clamored for action against some of the Browns players who menaced Vaughn. In the end, Vaughn lost his $25 but no other action was taken.

Vaughn was slow to report to training camp in 1894. He complained that after the season he had, his pay should be better than what Murphy made going into 1893. A contract was worked out and the Reds opened the season with a sweep of Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts team, but Vaughn was struggling defensively. His play was so bad one game that the local writer proclaimed, “Farmer Vaughn played yesterday like a man bereft of his senses.”14

At the plate, however, he was stroking the ball better than ever. He launched two home runs on May 30 in a doubleheader in Boston. Unfortunately for the Reds their pitching did not show up that day. Boston won the opener, 13-10, on a Hugh Duffy three-run homer. In the second game, the two teams blasted nine home runs, including four from Bobby Lowe. Boston won, 20-11.

Vaughn’s season came to an early close on August 1 in a game at Pittsburgh. While at bat against the Pirates, he threw up his arm to block a pitch sailing toward his head. He told the writers, “This is the first time in my eight years professional experience I have had to lay off more than one day … I had not been hit been hit a single time with a pitched ball before this season … One of the bones between my wrist and elbow is broken.”15 Vaughn was displaying selective amnesia, as records indicate he had been plunked seven times the previous two seasons. He ended the year with a .310 batting average and a slugging percentage of .482, both tops in his career.

Buck Ewing took over as manager of Cincinnati from Comiskey the following year and turned the team into a solid, first-division squad. Vaughn played catcher and first base from 1895-98. In 1899, he slumped badly and was relegated to the bench, getting released in mid-July. Comiskey was manager of the St. Paul Apostles in the Western League at this time and picked Vaughn up. He was inserted into the cleanup spot and played first base. Future major leaguer Frank Isbell was shifted to second to accommodate Vaughn.

As Vaughn’s major league days were ending, so was his marriage. Gertrude filed for divorce in February 1900 and asked for custody of their daughter Lona. The case dragged on and Vaughn stayed in the Cincinnati area and did not play baseball during that time. He made headlines in the summer of 1900 when he was accused of trying to kidnap Lona. The incident was written-off as a misunderstanding.16

However, a month later, Vaughn again tried to take his daughter. This time he was stopped by his brother-in-law, John McCracken, who threatened him with a shotgun. An assault trial ensued where McCracken was cleared after dramatic testimony from Mrs. Vaughn about her domestic troubles.17 The divorce court eventually held in favor of Gertrude and after additional wrangling amongst the attorneys, a judge set the alimony at $30 a month and granted Gertrude additional considerations.18

In 1902 Vaughn returned to baseball with the Peoria Distillers in the Class A Western League. He shaved off his signature mustache and handled first base for Peoria. In July he was released and joined the Western League Milwaukee Creams, where manager Hugh Duffy made him their right fielder. Vaughn ran afoul of the law again. This time he got into an altercation with a hotel manager and shot the man in the hand. Vaughn was fined $40 and costs for assault with a deadly weapon.19

In the offseason, Duffy sent a contract calling for a $100 a month decrease. Vaughn balked. He considered a return to his previous life as a tobacco broker, where he could live in Cincinnati and play on weekends with the semipro teams. An offer more to his liking came from the Birmingham Barons in the Class A Southern Association, so Vaughn packed his bags and headed south to play first base and bat cleanup. At age 39 he tied for the most at-bats on the team. His .306 batting average was the best for any Baron with over 100 at-bats.

With the Barons, Vaughn found a baseball home for the coming years. Midway through 1904 he took over as manager of the team, guiding it through the 1908 season. In the spring of 1904 he also coached the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (a.k.a. Auburn). The team played an ambitious 14-game schedule (they had played a total of 12 games the previous two seasons) but saw three rainouts. They had victories over Florida State and Alabama. “Farmer” planted the seeds for success as the next year the team went 9-3 and won their conference championship.

Vaughn’s ex-wife remarried a saloon keeper named Jack Kilroy. Vaughn had visitation privileges to see Lona without restrictions, but he still harbored feelings for his ex-wife. In January 1905 he was arraigned in Police Court in Cincinnati on a charge of disorderly conduct. He had supposedly brandished a revolver and made threats about his ex and Kilroy.

The 1906 Southern Association was a pitcher’s league, as only three hitters topped the .300 mark. The Birmingham Barons added Kaiser Wilhelm to their already powerful pitching corps, and the team burst out of the gates with five straight wins. Going into May their record stood at 16-5. Vaughn was intent upon the title and battled for every win. The results were numerous games that were protested either by the Barons or because of the Barons.

League President Kavanaugh heard nine protests in the first month. Many centered on Vaughn’s use of more than 14 men on his roster. Vaughn protested games because of misapplied rules by umpires and even because of “undue police interference.”20 After the hot start, the offense cooled and the Barons dropped off the pace. Through May and June, Shreveport and New Orleans occupied the top spot. Vaughn purchased first baseman Herman Meek from Toronto and inserted him into the cleanup spot.

Meek led the team in hitting with a .298 average. Shortly after his arrival, the Barons won 12 straight at the beginning of August to reclaim first place. They ran away from Memphis for the pennant. All the players were given signet rings. Meek and catcher Harry Mathews also received gifts along with Vaughn at the final game.

The team did not return to glory in his final two seasons. Meek led the league in hitting in 1907 and Wilhelm was one of the best hurlers, but the team sank in the standings. As baseball fate would have it, Vaughn found himself managing an aged Steve Brodie for a few weeks. In 1908 Vaughn was replaced in late May by Carlton Molesworth, who became a Birmingham legend. Vaughn’s removal came a few days after he threatened to fire all the players.

After his Birmingham tenure ended, Vaughn returned to Cincinnati. He ran a saloon with his nephew Orville “Sam” Woodruff for a while but lost the license on it in late 1913. His health had taken a major turn and the once trim 180-pounder put on weight. He died on February 21, 1914 after a short bout with pneumonia. Vaughn had joined the Elks when he was in Birmingham. Elks Lodge 79 in Cincinnati hosted his funeral service at their temple. He was cremated.21

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

When researching players from the Cincinnati area, the book The Local Boys by Joe and Jack Heffron is always useful. In this case it helped me with background on Vaughn.

Notes

1 Ren Mulford Jr. “Down in Pelican Land,” Sporting Life, March 7, 1914: 15.

2 “The Aftermath,” Sporting Life, September 29, 1906: 18.

3 Joe and Jack Heffron, The Local Boys (Birmingham, Alabama: Clerisy Press: 2014): 202.

4 The Pittsburgh Press, February 8, 1894: 5.

5 “A Thankless Task,” Sporting Life, June 17, 1899: 9.

6 “Stories of the Diamond,” The Pensacola News (Pensacola, Florida), July 3, 1903: 2.

7 The correct spelling of her first name is uncertain. Each census has a different version.

8 “Three Straight,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), April 20, 1887: 2.

9 “Throwing the Base-Ball,” Springfield Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), June 25, 1890: 5. It should be noted that many wire service reports called Vaughn’s toss a “new record.”

10 “Diamond Chat,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 7, 1890: 23.

11 “Comiskey’s Plans,” Sporting Life, April 8, 1893: 1.

12 “Dirty Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 16, 1893: 2.

13 T.C.Bancroft, “A Card From Bannie,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1893: 2.

14 “Errors,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 10, 1892: 2.

15 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 3, 1894: 2.

16 “Mistaken,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 1, 1900: 16.

17 “M’Cracken,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1900: 8.

18 “Child Cries for His Mother,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 7, 1901: 7.

19 “Harry Vaughn Fined,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 28, 1902: 4.

20 “Games Protested,” The Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery, Alabama), June 4, 1906: 8.

21 “Bury Vaughn Wednesday,” Cincinnati Post, February 24, 1914: 6.

Full Name

Henry Francis Vaughn

Born

March 1, 1864 at Ruraldale, OH (USA)

Died

February 21, 1914 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.