Fay Young

Frank Albert “Fay” Young was one of the most influential sportswriters in the Black press, during a career that spanned five decades. Modern scholars have praised him for his thorough coverage of Negro Leagues baseball,1 as well as for reporting on athletic events at historically Black colleges.2 Writing at a time when few Black newspapers were reporting about sports at all, and when most of the mainstream white newspapers seldom covered athletes of color, Young is often credited with being the first full-time Black sportswriter,3 as well as developing the Chicago Defender’s sports page,4 an idea that was soon emulated by other publications. He was frequently referred to by his peers as the Dean of Negro Sportswriters,5 and his columns, which included “Fay Says,” “The Stuff Is Here,” and “Through the Years,” were must-reads for sports fans.

Frank Albert “Fay” Young was one of the most influential sportswriters in the Black press, during a career that spanned five decades. Modern scholars have praised him for his thorough coverage of Negro Leagues baseball,1 as well as for reporting on athletic events at historically Black colleges.2 Writing at a time when few Black newspapers were reporting about sports at all, and when most of the mainstream white newspapers seldom covered athletes of color, Young is often credited with being the first full-time Black sportswriter,3 as well as developing the Chicago Defender’s sports page,4 an idea that was soon emulated by other publications. He was frequently referred to by his peers as the Dean of Negro Sportswriters,5 and his columns, which included “Fay Says,” “The Stuff Is Here,” and “Through the Years,” were must-reads for sports fans.

Young covered all major sports, including baseball, boxing, college football, and track; and in the era of segregation, he gave southern Black athletes attention they might never have received otherwise.6 In addition to covering sports rivalries at historically Black colleges,7 he chose an annual All-America college football team for the Defender, and was one of the founders of college football’s annual Prairie View Bowl game, held in Houston, Texas.8 He was also known for his strong support of Negro Leagues baseball, and he wrote about it often. He reported on the Negro National League (NNL) from its inception in early 1920; and throughout the decade, he not only covered many NNL games, but he also covered the league meetings,9 keeping his readers informed about what the owners and executives were doing.

As a baseball writer, Young’s main focus was on his home team, the Chicago American Giants; he even served as the de facto publicist for team owner, and NNL executive, Rube Foster,10 a man whom Young deeply admired and to whom, even years later, he referred as “the brains of Negro baseball.”11 It was a time when many sportswriters had close relationships with the teams they covered, and tried to offer positive and optimistic stories whenever possible.12 Thus, Young’s advocacy for the Negro Leagues, and his support of Foster, might not have seemed surprising to fans back then. And in what also might be seen as a conflict of interest by today’s standards, Young sometimes worked as the official scorer for the Giants, while he was also covering the team’s exploits for the Defender.13 (In fairness to Young, he was respected for his knowledge of baseball’s rules, and he was sometimes chosen as the official scorer for games that did not involve the Giants, like a 1924 series between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Hilldale Club.)14 He continued to report on the Negro Leagues, and focus on the accomplishments of Black ballplayers, throughout his career. When the Negro American League was created in 1937, he was named one of its officers.15 He later served as the publicist for the league.16

But despite his love for Negro Leagues baseball, he was not shy about questioning the league’s business model;17 and he spoke his mind when he disagreed with decisions the league’s management made. For example, in the NNL’s first several years, all of its umpires were white, a situation that both mystified and upset Young, who wondered why the league had not hired any black umpires yet.18 He also chastised some of the owners for getting involved in petty squabbles with each other, rather than doing what was best for the league.19 In addition, he spoke out whenever ballplayers were behaving badly: He believed the ones who lost their temper and acted like “hot heads” whenever an umpire made a call they disliked were making the game less family-friendly, and thus contributing to lower attendance.20 He also had little patience for players who didn’t stay in shape, or who partied too much.21 And as someone who not only reported on the Negro Leagues but was also a fan himself, he sometimes wondered why the local teams did not receive more support from the Black community. He wrote that he could not understand why Black baseball fans preferred to go and see two all-white teams play when there were talented Negro Leagues teams that were equally worth watching.22

Young’s birth name was John Lake Caution, Jr. Born in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, on October 19, 1884, he was the oldest of four children of John Lake Caution, a mill worker, and his wife Annie (Collins). His early years were difficult: His mother died when he was five, and several years later, his father was killed in a mill accident. The children’s paternal uncle and aunt, Cornelius and Ella (Blake) Caution, who lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, took them in. But Ella died of cancer a few months after the children arrived, and they were all sent to an orphanage.23

The four children were ultimately adopted, but by different families: John’s sister Ethel by a Boston widow named Mary M. Davis; his brother Russell by an aunt, Louise Caution of Johnstown, New York; and John, along with his sister Belva, by William F. Overton, a gardener, and his wife Margaret, who lived in West Medford, Massachusetts. There is very little written information about this period in John’s life. Census documents from 1900 show that he was living with the Overtons and attending high school. But at some point, he seems to have had a disagreement with the family, and he decided to leave. He made his way to Chicago not long after that, although we have little information about why he decided to settle there. We know from one of his later Chicago Defender columns that he recalled selling newspapers on the streets of Chicago,24 and he subsequently got a job as a Pullman porter on the Chicago and North Western Railway. In December 1905, he married Adeline Harris, and they had two children. However, the marriage ended in divorce, and in September 1918, he married Cora K. Bowman.

It was in Chicago where he reinvented himself as Frank Albert Young (his nickname “Fay” came from the initials of his new name). Interviews with his great-great-grandson suggest a possible reason why he decided on that name. While still living West Medford, Massachusetts, where he was known as Jack Overton, he became friendly with a neighbor, Frank Arthur Young, who was attending Harvard, something few Black students did at that time. (Records from the Harvard University Archives verify that the young man was attending the dental school.) Family lore suggests that Jack saw his neighbor as a mentor and someone he admired. When he moved to Chicago, he wanted a new identity, and he decided upon a version of his former neighbor’s name—he became Frank Albert Young.25 (His sister Belva, with whom he kept in touch, first heard he was using “Bertie Young,” before becoming known as Frank.)26

While he was working for the railroad, he met a black entrepreneur named Robert Abbott, who had founded a newspaper, the Chicago Defender, in 1905. Abbott’s goal was to reach out to black readers in cities across the United States, including some in the then-segregated South. Young, who was now working in the dining car as a waiter, agreed to help distribute the new publication; he also encouraged his fellow porters and waiters to help. They began surreptitiously carrying copies with them to be dropped off and sold in other cities.

We do not know if Young had ever considered a career in journalism, but he became a valuable resource for Abbott. Because he talked with a lot of people during his travels, Young was able to report the news and gossip he heard from each city, and some of that information ended up in the Defender.27 That may explain why Abbott invited him to join the newspaper’s staff, although in those early days, there was little money for paying anyone. The exact date when Young first began working as a reporter is uncertain: Some sources say that he started as early as 1907,28 or perhaps 1908.29 But by most accounts, during the Defender’s formative years, he volunteered his time, while still working for the railroad. In those early years with the newspaper, he was a general assignment reporter; in addition to his own reporting, he helped with writing and editing other stories. But he did not cover sports very often; his first bylined sports articles began appearing in the Defender around 1912.30 (Over the years, his byline would sometimes be “Frank Young,” or “Frank A. Young,” or “Fay Young,” or “Frank ‘Fay’ Young.”) As for when he left the railroad to work in journalism full time, that too is not certain: There are sources that say he was hired full time in 1911;31 but others, including a former colleague, have placed the date as late as 1915.32

As soon as the Defender’s circulation had increased enough to allow Robert Abbott to hire additional reporters, Young was finally able to focus more of his time on the sports beat, ultimately becoming the Defender’s sports editor. Meanwhile, Abbott moved him into other management positions: By 1916, he was working as the newspaper’s business manager,33 and by the late 1920s, he had been named the Defender’s managing editor.34 Young would spend nearly all of his journalism career at the Defender, with the exception of a three-year period during which he was the managing editor of the Kansas City Call. Many sources give 1934-1937 as the time when he was there,35 but there is evidence he was working at the Call as early as 1932;36 in fact, he was listed in the 1932 City Directory for Kansas City as a resident of that city, and the Call’s managing editor. In addition, during the early 1930s, Young wrote some articles for Robert Abbott’s short-lived magazine, Abbott’s Monthly, including one about William “Doc” Buckner, an African-American trainer who worked for the Chicago White Sox in the 1910s.37 He also wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier,38 and the Associated Negro Press syndicated his columns to other publications, including the Baltimore Afro-American.

But no matter where he worked, Young became known for his thorough reporting on local athletic events, whether professional baseball or college sports. He was among the first Black sportswriters to travel to historically Black colleges and cover their teams.39 Today, we take on-the-scene reporting for granted, but in segregated America, getting to the stadiums (and some of the ballparks), especially in the Deep South, was not easy: Young once remarked that it might take an entire day for a Black reporter to get to an event.40 A talented writer and story-teller, he had an eye for interesting details, and no matter which sport he was covering, he made his readers feel as if they were there.

Young’s articles on baseball demonstrated not only his affection for the sport but his knowledge of the finer points of the game. And although he loved his home-team Chicago American Giants, he tried to report on them fairly, avoiding too much boosterism. If they played well, he praised them, but if they didn’t, he made no excuses, writing about one playoff game in 1926 when the Giants were “weak at the bat” and didn’t seem to want to win as much as their opponents, the Kansas City Monarchs, did; and the next one, where, while the Giants had some “bad luck,” it was poor defensive play that cost them the game.41

Young also had a deep appreciation for good players, even if they were on the opposing team: For example, he wrote very positively of John ‘Steel-Arm’ Dickey of the Montgomery Grey Sox, who was the Southern League’s leading pitcher, when his team came to Chicago in mid-September 1921 to play the Giants. Dickey and Giants’ pitcher Dave Brown were locked in a pitching duel, and Young was impressed by both men—in fact, he said that Dickey’s pitching was “wonderful.” But Brown’s was just as good, and thanks to a 9th-inning Grey Sox error, the Giants won the game, 1-0, sending 14,000 fans home happy.42 When he wasn’t reporting on the games, Young began writing a regular sports opinion column; one of his first was titled “Fay Says.” This column debuted on September 23, 1921, and it continued off and on till the late 1940s. When he returned from working in Kansas City, he started another opinion column, “The Stuff Is Here…Past—Present—Future,” in August 1937; around January 1942, this column was re-named “Through the Years.”

During the early 1930s, the Depression caused financial hardships for numerous teams, in the Negro Leagues as well as in Major and Minor League Baseball. Fans could no longer afford tickets, and attendance plummeted in many cities; some white minor-league clubs went out of business, as did several Negro Leagues teams. And even the teams that survived suffered severe financial losses.43 The NNL itself did not survive; it ceased operating at the end of 1931, eventually reemerging in a second incarnation in 1933. Meanwhile, when the Negro American League was organized in 1937, Young became one of its officers, serving as the league’s secretary,44 a role he maintained till the late 1940s.

Throughout his career, Young was widely respected for his encyclopedic knowledge of sports, and younger writers looked up to him.45 He also had a reputation for being outspoken, and he was a man who did not suffer fools gladly (one of his contemporaries referred to him as “irascible,”46 and another said he could be “caustic”47). But everyone knew how passionate he was about Negro Leagues baseball, and he saw himself as its “self-appointed conscience.”48 Whenever attendance was low, he would use his columns to exhort local fans to come to the ballpark and support their team. In a 1939 column, he not only expressed his disappointment that more black fans had not come out to see that year’s East-West All Star Game, but he was equally dismayed that more white fans hadn’t been in attendance.49 He also believed certain owners bore some responsibility for the attendance problems: He sometimes remarked on how these owners failed to give their teams sufficient publicity.50 (That may explain why he got involved with doing the publicity for the Negro American League in the mid-1940s. He was also the publicist for the tenth annual East-West All Star Game in 1942.)51

One area that he frequently discussed was the need for Major League Baseball to integrate. As far back as the mid-1920s, he wrote that Major League Baseball’s ban on Black players was “silly… and [it] should be removed.”52 Along with other well-known Black sportswriters like Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, and Joe Bostic, he regularly advocated for African-American players to be given a chance to play in the Major Leagues. In a 1938 article, he offered a long list of Black players who, he believed, were every bit as good as the white players on Major League teams—among them were Negro Leagues All-Stars like Josh Gibson, “the Negro Babe Ruth,” Ray Dandridge, Buck Leonard, and Walter Cannady. His article concluded, “Since the great game of baseball is called the ‘American Pastime,’ let it be really American for and by Americans regardless of race, creed or color.”53 And in another article from that year, Young mocked the white owners and managers who claimed they really wanted to sign some Negro Leagues players, “if only they could,” yet who made excuses or “passed the buck” when an opportunity to implement change presented itself. And he called out Washington Senators’ president Clark Griffith, who said in an interview that the time was not right yet to integrate, and besides, there weren’t enough Black players who were ready for the Major Leagues, dismissing Griffith’s comments as the “same old bunk.”54

Young also articulated the outrage Black fans felt when a white player made a racist remark, as New York Yankees outfielder Jake Powell did, during a pregame radio interview broadcast by Chicago station WGN on July 29, 1938. Powell, who claimed that he was a policeman in the offseason, said he kept in shape by “cracking n****s over the head” with his nightstick, as he walked his beat.55 While some white fans were surprised to hear the “N-word” on radio, others seem to have been amused by it. But the Black audience, and many Black baseball writers, were furious that a major league ballplayer would say something so offensive. Black fans demanded that Powell face some punishment; they also threatened to boycott the games. And since Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert also owned a brewery, there was talk of boycotting his beer. Powell was given a ten-game suspension by Baseball Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, but to Black fans, and to Young, that seemed like an inadequate penalty. He wrote, “Jake Powell has no business in organized baseball … He has no business traveling a beat as a member of the Dayton, Ohio police force … Jake Powell is the type that causes race riots …” Young went on to say that “Powell said what he meant … My race is not pacified by the ten-day fine, and Judge Landis and Powell’s boss don’t need to think we are.”56

In addition to writing about Negro Leagues games and advocating for better pay and better treatment for Black players, Young also enjoyed reminiscing about the past. Sometimes, he wrote historical columns, where he recalled the great games he had witnessed, or the old-time players he admired. He had a certain nostalgia for the days when Rube Foster was alive and well: In one article, written in 1942, he took readers back to 1909, to talk about the Leland Giants, which Foster managed; the team won 66 games and lost only 26 (with two ties). And as Young recalled the team and its players, he also discussed old Chicago, remembering the stores, the hotels, and the places where fans gathered, in a city that now looked so different.57

In 1945, Major League Baseball finally signed its first Black player, Jackie Robinson, and Young was among the sportswriters who felt a sense of satisfaction, having advocated for integration for many years. He wrote that this was certainly something worthy of celebration: “Democracy has finally invaded baseball, our great national pastime.”58 But he was also aware that signing one Black player was just a first step, and much more needed to be done. In addition, he reminded Black fans that they would be on trial, just like Robinson was. Whether it was fair or not, white fans and reporters would be watching them, and he reminded Black fans to be on their best behavior—to avoid drinking or using vulgar language since, “The unruly Negro has and can set us back 25 years.”59

After Robinson made his major league debut in 1947, Young continued to believe there was a role for Negro Leagues baseball, but what that role was remained uncertain. Like many Black baseball writers, he was now covering more major league games than in the past, but his heart was still with the Negro Leagues. He even implored Negro American League fans to “roll up our sleeves and give [our] team our fullest support.”60 But the quality of the play was deteriorating, and fans were not showing up in sufficient numbers for the teams to make any money. By 1953, even an event that used to bring in lots of fans, the East-West All Star game, drew a dismal crowd. One person who was not there was Young—league management had for some reason, failed to invite him.61

Despite ongoing health problems, Young continued to cover sports well into the 1950s. Although he had supposedly retired in 1949, he still came into the Defender offices now and then, to talk sports with his colleagues, and he still wrote some opinion columns, as he had done for decades. (In fact, he submitted his final column only a few days before he died.) In his later years, he won numerous awards, including one from the Pigskin Club in Washington, D.C. in 1955 (an award he shared with Jackie Robinson, for exemplifying “clean sports and fair play.)62 And he was given an honorary degree from Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute (today Tuskegee University) in 1956.63

In addition, he was recognized for his philanthropy: Because he had contributed geese, ducks, and pheasants to the Department of Poultry Husbandry at Tennessee State Agricultural and Industrial College (today known as Tennessee State University), the school named its new poultry plant after him in 1953. His colleague, Russ Cowans, who succeeded him at the Defender, also noted that Young was very generous in offering help to others, including assisting students who needed help paying their tuition.64

Frank “Fay” Young died at his Chicago home on October 27, 1957, at age 73. He had been in poor health for a while but had still been planning to go to New York to attend his sister Belva’s funeral. She had died two days earlier, and some newspapers said the shock of her death contributed to his.65 Today, baseball historians and researchers continue to benefit from Young’s in-depth reporting about the Negro Leagues. Historian Paul Debono has called Young “one of the greatest baseball writers of all time … an unsung hero of black baseball.”66

Those who knew him personally praised Young’s willingness to stand up for Black sportswriters: He fought to get them admitted to the press boxes that had previously been reserved for white reporters only. As Bill Nunn Jr., a reporter for the Pittsburgh Courier, said, “He helped us gain first-class citizenship in a profession that once resented the presence of Negroes.”67 In his day, Young was a role model for other Black sportswriters, and in modern times, he remains an invaluable resource: His insights and commentary, along with his thorough game summaries, help us to better understand Black baseball in the era before integration.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank two reference librarians for their invaluable assistance: Donna Hesson from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland; and retired librarian J. A. “Andy” Stewart from Ellicott City, Maryland.

The author is grateful to Jewell Young, Fay Young’s great-great-grandson, for filling in some missing details about Fay’s youth. And the author is also grateful to the Harvard University Archives for verifying Frank Arthur Young’s attendance in 1896-1897.

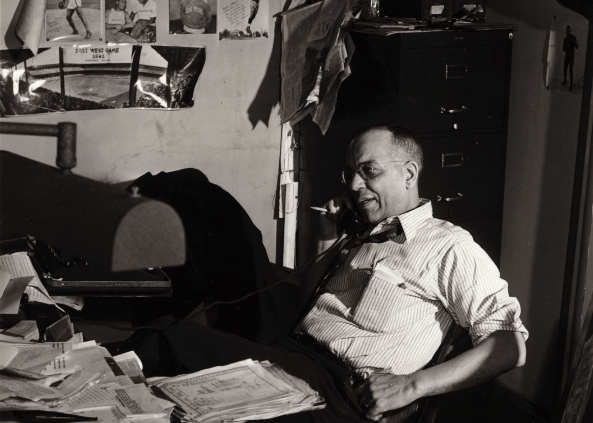

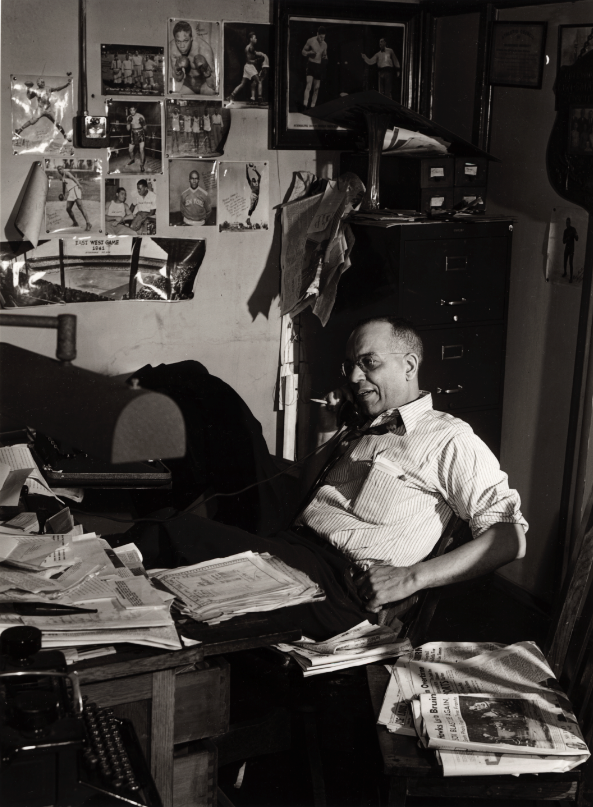

Additionally, the author wants to thank the International Center for Photography for permission to use the photograph of Fay Young: Jack Delano, “Frank Young, better known as FAY, sports editor of the Chicago Defender, 1942.” International Center of Photography, Museum Purchase, 2003 (76.2003)

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Joel Barnhart, and fact-checked by Chris Rainey. It was originally published in August 2020 and updated in November 2020.

Notes

1 For example, Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007), 222.

2 Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

3 Brian Carroll, When to Stop the Cheering? The Black Press, the Black Community, and the Integration of Professional Baseball, (New York: Routledge, 2007), 49.

4 Albert Barnett, “Fay Young, Dean of Sports Scribes, Passes,” Indianapolis Recorder, Nov 2, 1957, 11.

5 See for example, “Sports Editor Seriously Ill,” Tampa Bay Times, May 23, 1949: 15; and “Honorary Degrees by Tuskegee,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 26, 1956, 17.

6 A.S. “Doc” Young, “The Black Sportswriter,” Ebony, October 1970, 64.

7 Derrick E. White, Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Jake Gaither, Florida A&M, and the History of Black College Football, (University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 30.

8 Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

9 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 121.

10 Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 73

11 [Frank] Fay Young, “The Stuff is Here,” Chicago Defender, September 11, 1937, 20.

12 Brian Carroll, When to Stop the Cheering? The Black Press, the Black Community, and the Integration of Professional Baseball, (New York: Routledge, 2007), 49-50.

13 Brian Carroll, The Black Press and Black Baseball, 1915-1955: A Devil’s Bargain, (New York: Routledge, 2015), 9.

14 “Among Our Group,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 11, 1924, 11.

15 Doron Goldman, “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” Society for American Baseball Research, 2018: https://sabr.org/research/negro-leagues-business-meetings-1933-1962

16 “Negro Baseball Reorganizes into One 10-Team League,” Dayton (Ohio) Daily Express, December 9, 1948, 1.

17 Frank ‘Fay’ Young, “Fay Says: Yes or No?” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1922, 10.

18 Brian Carroll, “From Fraternity to Fracture: Black Press Coverage of and Involvement in Negro League Baseball in the 1920s,” American Journalism (Spring 2006), 80

19 Brian Carroll, “To Pittsburgh from Chicago: A Changing of the Guard in Black Baseball and the Black Press in the 1930s,” Black Ball, Volume 2, #2 (Fall 2009), 89.

20 Fay Young, “The Stuff is Here,” Chicago Defender, August 28, 1937, 20.

21 quoted in Brian Carroll, “From Fraternity to Fracture: Black Press Coverage of and Involvement in Negro League Baseball in the 1920s,” American Journalism (Spring 2006), 81.

22 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007), 145.

23 Mary Sieminski, “Williamsport Women,” Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Sun-Gazette, July 10, 2016, E-1, E-3. Online version at https://www.sungazette.com/life/lifestyle-news/2016/07/williamsport-women/

24 [Frank] Fay Young, “Through the Years,” Chicago Defender, July 4, 1942, 19.

25 Interview with Fay Young’s great-great-grandson, Jewell Young, conducted via email and via Zoom on November 21, 2020.

26 “Tracing ‘Overton.’ May Have Lived Formerly in Medford,” Boston Globe, September 3, 1905, 2.

27 Albert Barnett, “Fay Young, Dean of Sports Scribes, Passes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 2, 1957, 11.

28 Leslie Heaphy, “Dean of Sportswriters: Frank ‘Fay’ Young,” Black Ball, vol. 3, #2 (Fall 2010), 47.

29 Ethan Michaeli, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America, (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 23.

30 Frank A. Young, “The World of Sports,” Chicago Defender, October 26, 1912, 7.

31 Ethan Michaeli, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America, (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 37.

32 Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

33 “Afro-American Cullings,” Kansas City Sun, January 6, 1917, 7.

34 Leslie Heaphy, “Dean of Sportswriters: Frank ‘Fay’ Young,” Black Ball, vol. 3, #2 (Fall 2010), 47.

35 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016), 78.

36 Frank A. Young, “Suggests Spingarn Medal for Tolan,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 13, 1932, 16.

37 Frank A. Young, “Bill Buckner, Greatest Trainer of Baseball Players,” Abbott’s Monthly, 16-19, 65. (This issue, including Young’s article, has now been digitized by the Smithsonian, and can be found here: https://transcription.si.edu/project/23335)

38 “Joins Courier Family,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1931, 1.

39 Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

40 See: A.S. “Doc” Young, “The Black Sportswriter,” Ebony, October 1970, 64; and Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

41 Frank A. Young, “Monarchs Lead American Giants,” Chicago Defender, September 25, 1926, 11.

42 Frank Young, “It’s All in the Game,” Chicago Defender, September 17, 1921, 10.

43 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing, (Syracuse University Press: 1994), 220-221.

44 Christopher Hauser, The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948, (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2008), 101.

45 A.S. “Doc” Young, “The Black Sportswriter,” Ebony, October 1970, 64.

46 Johnny Johnson, “East-West Game Faces Death in Chicago Park,” Kansas City Call, August 21, 1953, quoted in Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, (University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 387.

47 A.S. “Doc” Young, “The Black Sportswriter,” Ebony, October 1970, 62.

48 Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 66.

49 Frank “Fay” Young, “Fay Says,” Chicago Defender, September 9, 1939, quoted in Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, (University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 137.

50 [Frank] Fay Young, “The Stuff is Here,” Chicago Defender, September 11, 1937, 20.

51 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, (University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 460.

52 quoted in Leslie Heaphy, “Dean of Sportswriters: Frank ‘Fay’ Young,” Black Ball, vol. 3, #2 (Fall 2010), 48.

53 Frank A. Young, “Dandridge as Good as Mel Ott at His Best,” Chicago Defender, September 24, 1938, 9.

54 Frank A. Young, “Dixie Whites Would Not Quit Big Leagues If Our Men Could Play,” Chicago Defender, June 25, 1938, 9.

55 Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 109.

56 [Frank] Fay Young, “The Stuff Is Here,” Chicago Defender, August 6, 1938, 9.

57 [Frank] Fay Young, “Through the Years,” Chicago Defender, July 4, 1942, 19.

58 [Frank] Fay Young, “End of Baseball’s Jim Crow Seen With Signing of Jackie Robinson,” Chicago Defender, October 3, 1945, 9.

59 [Frank] Fay Young, “Through the Years,” Chicago Defender, April 19, 1947, 19.

60 [Frank] Fay Young, “Through the Years,” Chicago Defender, May 8, 1948, 11.

61 Johnny Johnson, “East-West Game Faces Death in Chicago Park,” Kansas City Call, August 21, 1953, quoted in Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, (University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 387388.

62 “Young, Robinson to Be Cited,” Sporting News, November 30, 1955, 24.

63 “Honorary Degrees by Tuskegee,” Pittsburgh Courier, 26 May 1956, 17.

64 Russ J. Cowans, “Fabulous Fay,” Chicago Defender, November 9, 1957, 11.

65 Albert Barnett, “Fay Young, Dean of Sports Scribes, Passes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 2, 1957, 11.

66 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007), 220.

67 Bill Nunn Jr. “Change of Pace,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 9, 1957, 26.

Full Name

Frank Albert Young

Born

October 19, 1884 at Williamsport, PA (US)

Died

October 27, 1957 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.