1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball

This article was written by Doron Goldman

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (2021)

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in “Baseball’s Business: The Winter Meetings, 1958-2016” (SABR, 2017), was honored as a 2018 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winner.

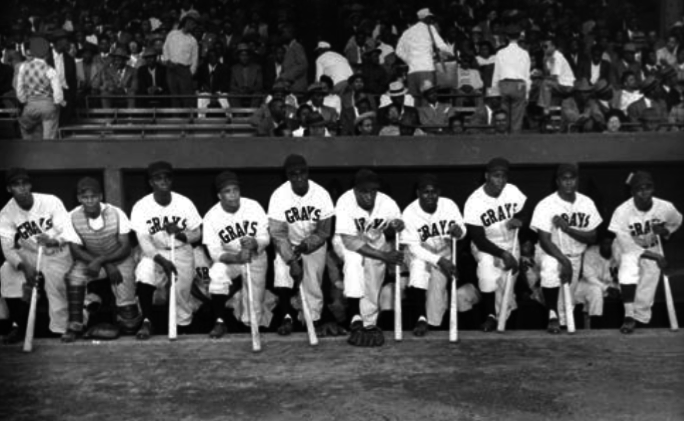

Negro League baseball magnates meet at the Hotel Teresa on June 20, 1946, in New York City. The owners had all attended the Joe Louis boxing bout the night before. The meeting was to plan the second-half schedule for the 1946 season. Left to right: Syd Pollock (Indianapolis Clowns), Tom Wilson (Baltimore Elite Giants), Tom Baird (Kansas city Monarchs), W.S. Martin (Memphis Red Sox), J.B. Martin (NAL President and Chicago American Giants), Ernest Wright (Cleveland Buckeyes), Fay Young (Chicago Defender writer), Wilbur Hayes (Buckeyes), and Tom Hayes Jr. (Birmingham Black Barons). (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

By Doron Goldman

Although the first organized and sustainable Negro League, the original Negro National League (NNL), founded by Rube Foster in 1920, did not survive the Great Depression, it was the forerunner of several other Negro Leagues. In the 1920s, the Eastern Colored League (ECL) was formed as a counterpart to the NNL. It lasted from 1923 through the early part of 1928, then was succeeded by the American Negro League (ANL) for one year in 1929. The first NNL, largely based in the Midwest, continued its operations into the 1930s, but was replaced in 1932 by another short-lived organized league called the East-West League. Like the ANL, the East-West League survived only one year.

In 1933, several events of marked importance occurred: Franklin Delano Roosevelt started his 12-year presidency, Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany — and the second NNL began operations. This incarnation of the NNL was a hybrid of Eastern and Western clubs, including the developing twin powerhouse Pittsburgh franchises the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, along with Midwestern mainstay the Chicago American Giants (at that time referred to as Cole’s American Giants as Robert Cole took over ownership in 1931), the team that Rube Foster pitched for and owned while he started the original NNL.1 Though this NNL began operations during the depths of the Great Depression, it managed to survive the 1930s, thrive during the wartime ’40’s, and then begin to struggle as soon as Jackie Robinson signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1945 to begin playing with the Montreal Royals in 1946.

It is important to note here that the second NNL started right after “the most harrowing four months” of the Depression, when the US economy had hit rock-bottom.2 According to historian David Kennedy, African-Americans during the Depression represented one-fifth of the people on federal relief, approximately twice their population percentage at the time.3 That the 1933 NNL was able to get off the ground during these difficult times for all Americans (but especially for the black population) is a testament to the determination of the owners who were committed to re-establishing organized black baseball at a level at least comparable to the original Negro National League.

As referred to by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, the “Golden Years” of Negro League Baseball that began in 1933 with the re-established NNL and was augmented by a second competing Negro League, the Negro American League (NAL), starting in 1937, began to slowly close as the NNL ended operations after the 1948 season.4 The NAL, however, survived, with yearly fluctuations in the number of teams it fielded, through the 1950s. Many commentators consider 1960 to be the last year of the NAL’s operations, but others point to limited activity among NAL teams through 1962.

This article is not meant as a complete history of the 30 seasons of Negro League competition through 1962; although references to the on-field performance of the NNL and NAL during this period will be made, along with the star players who populated the legendary teams in each league, the primary focus will be an examination of the often contentious business dealings of team owners within the NNL and NAL as well as the internecine conflicts between the two leagues for their 12-year coexistence. Although what follows will include yearly reports of winter and, when available, in-season meetings of the NNL, NAL, and joint meetings of the two leagues, it will also group the analysis into four distinct periods:

- Birth and Growth (1933-1940): The New NNL and the beginnings of the East-West (E-W) Game (1933) and the birth of the NAL (1936) and fledgling years of two-league play (1937-1940).

- War and Prosperity (1941-1945): The heyday of black league baseball — the two leagues profit and the Negro World Series (NWS) and E-W Game thrive.

- Integration and Storm Clouds—The NNL’s Demise (1945-1948): Jackie Robinson signs with Brooklyn and Negro League owners see drastic business decline, culminating in the end of the NNL.

- The Surviving NAL — The End of the Negro Leagues (1949-1962): League membership expands and contracts from the late 1940s through the early 1960s as the Negro Leagues struggle to survive — through the last E-W Game on August 26, 1962.

(Click on a link above to scroll down to that section of the article.)

The primary source material for this article is the black press; however, as referenced by several reporters and columnists who were frustrated by Negro League owner practices, the owners could be secretive about their boardroom discussions; this meant that sometimes the press reported that a meeting was upcoming along with the planned agenda but then did not cover the meeting afterward. Over time, though, this began to change, especially as those involved wrote their own columns describing conflicts between owners in self-serving ways.5 It is those columns, as well as several excellent secondary sources that have delved into Negro League operations and the correspondence and meeting minutes found in Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley’s files that form the basis of this chronicle.

PART 1: BIRTH AND GROWTH (1933-1940)

Pre-1933

Even though Rube Foster, the founder of the first NNL in 1920, had ceased to be involved in its operations by late in the 1926 season due to his own mental breakdown, the league managed to survive — barely — through 1931.6 It did not take long, however, for “Eastern and Western cities east of Chicago” to plan a meeting in Cleveland for January 20 and 21 of 1932. The cities to be included in this meeting were New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit. A “Cuban team representative” was also expected, while Kansas City’s Monarchs were there to join the league as an associate member.7 As an associate member, Kansas City would pay a smaller franchise fee and be included in league scheduling, but would not be counted in league standings and therefore could not play in any postseason games.8 The resulting league, named the East-West League, operated through mid-1932, when it also foundered despite the best efforts of team owners like Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays, J.L. Wilkinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, and Syd Pollock of the Cuban House of David.

Even though Rube Foster, the founder of the first NNL in 1920, had ceased to be involved in its operations by late in the 1926 season due to his own mental breakdown, the league managed to survive — barely — through 1931.6 It did not take long, however, for “Eastern and Western cities east of Chicago” to plan a meeting in Cleveland for January 20 and 21 of 1932. The cities to be included in this meeting were New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit. A “Cuban team representative” was also expected, while Kansas City’s Monarchs were there to join the league as an associate member.7 As an associate member, Kansas City would pay a smaller franchise fee and be included in league scheduling, but would not be counted in league standings and therefore could not play in any postseason games.8 The resulting league, named the East-West League, operated through mid-1932, when it also foundered despite the best efforts of team owners like Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays, J.L. Wilkinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, and Syd Pollock of the Cuban House of David.

In addition to the short-lived E-W League, 1932 saw a previously minor-league Negro Southern League (NSL) achieving short-lived major-league status. Though incarnations of the NSL existed prior to 1932, they were exclusively constituted by Southern teams; in 1932, in addition to the Monroe, Louisiana, Monarchs, Louisville Black Caps, Nashville Elite Giants, and teams in Houston, Birmingham, and Pittsburgh, the last of which was an associate member that quit before the end of the season, the league included former NNL teams like the Chicago American Giants, the Indianapolis ABCs, and the Cleveland Cubs. Unlike the E-W League, the 1932 NSL struggled through a fragmented second half to a conclusion culminating in a “World Series” between NSL champion Monroe and E-W League member Pittsburgh Crawfords.9 The loose, ragged nature of league competition in black baseball in 1932 raised a very simple question: What league or leagues, if any, would there be in 1933?

1933

The remnants of the aborted E-W League and the non-Southern 1932 NSL teams met in the first months of 1933 to see if the NNL could be revived. For one thing, as pointed out by Chicago Defender writer Ben Diamond, those Northern teams that played in the NSL in 1932 learned a lesson — that it was futile to “cram inter-sectional games down the throats of ‘up North fandom.’” Those fans, Diamond suggested, felt that the South “comprises minor league territory and you cannot make them see it differently.”10 Instead, by the end of 1932 there had already been two meetings including the Northern NSL teams, other E-W League teams, former NSL team representatives, and only one Southern team (albeit one that was reportedly considering moving North), the Nashville Elite Giants.11

And faithful reporter and former player and soon-to-be NNL manager of the Columbus Blue Birds William “Dizzy” Dismukes let it be known in the year-end edition of the Pittsburgh Courier that an organizing meeting of the new league, the first meeting of 1933, would be held in Chicago on January 10, 1933.12 Dismukes had some strong opinions about what ailed the prior Negro Leagues, and what was needed going forward. For one thing, he believed that the new league should pick among its owners a single league president or a three-man commission, as hiring an outsider he deemed to be unaffordable. This viewpoint foreshadowed a repeated battle between changing ownership factions who favored an insider as league head and other factions who favored a theoretically unbiased outsider non-owner as the league’s chief executive.

Dismukes had other opinions — that there should be no salary limit on an owner’s payroll, that a 5 percent pool from league receipts should be awarded to the new league’s 1933 pennant winner since there would not be two strong leagues to play a season-ending World Series, and that player averages should be reported twice a month, among other things.13 Dismukes would get his say as he was chosen to be the secretary of the new NNL along with the league’s statistician — he would be the one to report league averages — although he would eventually step down from this position to manage the short-lived Columbus team.14

Meanwhile, William A. “Gus” Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, was chosen as the temporary chairman of the new incarnation of the NNL at the organizing meeting in Chicago.15 Greenlee had funded his operations — two hotels, the Crawford Grille restaurant, and his baseball team — through the illegal numbers lottery.16 But there was another side to the story — Greenlee was seen by the Pittsburgh black community as a benefactor, not a racketeer. There were countless stories of the help he gave poor black citizens, including operating a soup kitchen during the Great Depression.17 According to Negro Leagues historian Jim Overmyer, the funding derived from “numbers bankers” who enabled the “launching [of] a league in the teeth of the Depression. As Rufus Jackson’s widow told an interviewer in Pittsburgh in the 1960s, “Well, of course they were involved — they were the only ones with any money.”18 Rufus Jackson later was recruited by Greenlee’s “very bitter baseball rival” Cum Posey to fund the operations of his Homestead Grays, while other numbers operators like Alex Pompez and Abe Manley later became owners of the New York Cubans and Newark Eagles, respectively.19

Meanwhile, William A. “Gus” Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, was chosen as the temporary chairman of the new incarnation of the NNL at the organizing meeting in Chicago.15 Greenlee had funded his operations — two hotels, the Crawford Grille restaurant, and his baseball team — through the illegal numbers lottery.16 But there was another side to the story — Greenlee was seen by the Pittsburgh black community as a benefactor, not a racketeer. There were countless stories of the help he gave poor black citizens, including operating a soup kitchen during the Great Depression.17 According to Negro Leagues historian Jim Overmyer, the funding derived from “numbers bankers” who enabled the “launching [of] a league in the teeth of the Depression. As Rufus Jackson’s widow told an interviewer in Pittsburgh in the 1960s, “Well, of course they were involved — they were the only ones with any money.”18 Rufus Jackson later was recruited by Greenlee’s “very bitter baseball rival” Cum Posey to fund the operations of his Homestead Grays, while other numbers operators like Alex Pompez and Abe Manley later became owners of the New York Cubans and Newark Eagles, respectively.19

It is fair to conclude that Branch Rickey’s later characterization of Negro League baseball as a racket, in order to justify his signing of Jackie Robinson without compensation to his Negro League team, the Kansas City Monarchs, was based in part on the illegality of the numbers operations engaged in by owners like Greenlee and Pompez. Rickey, however, was willing to partner with Greenlee in the development of the United States League (USL) when it suited his purposes, as Rickey’s involvement in that league provided a subterfuge for his scouting of black players for Brooklyn. In the end, as Overmyer pointed out, the illegality of numbers games at that time was by state statute — whereas today, state governments make money through the lottery, a modern version of the numbers lottery.20

In the February 11, 1933, edition of the Courier, columnist W. Rollo Wilson reported that chairman Greenlee had recently met in Philadelphia with Eastern owners including teams from Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Washington, Harrisburg, and Newark to form an Eastern division of the new league who would play primarily within their division with some lesser number of games to be played against the “West division,” culminating in a “world’s title” match at season’s end.21 Several of these teams, including Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, Newark, and Washington, were represented by proxy at a February 15 league meeting held in Indianapolis, with one more meeting scheduled prior to the league’s commencement for schedule-making.

The Eastern division of the 1933 NNL never materialized; according to author Neil Lanctot, Greenlee “abandoned a tentative plan for a separate eastern league after encountering resistance and a general lack of enthusiasm.”22 Already, tensions between ownership factions were evident, as can be seen by contrasting reportage from “Eastern” (in this case, Pittsburgh) and Western (Chicago) sources. Rollo Wilson’s Courier column of March 4, 1933, praised Greenlee as having the makings of a good president. Wilson suggested that Greenlee was anointed permanent chair of the NNL due to his hard work as the temporary head, spreading the word in various cities of the new league’s advent. Wilson extolled Greenlee for the building of Greenlee Park in 1932 and for the force of his vision and willingness to spend to achieve it.23

Meanwhile, in a more oblique piece, Al Monroe of the Chicago Defender, in his “Speaking of Sports” column of February 25, 1933, questioned why the East was put in “direct control of the league even though its idea was conceived and its first meeting arranged by and in the West.”24 While conceding that the East had more experienced hands for running the ship of the NNL, Monroe also cast a wary eye backward to the failed E-W League operations of 1932 and saw a “mark of similarity” in the 1933 setup. If, Monroe said, the leadership did what they promised, success would ensue but the West had valuable resources (“players and managers”) that must also be employed if this league would echo the success of Chicagoan Rube Foster’s first NNL. Monroe therefore felt that the newly constituted NNL should be led but not dominated by Pittsburgh’s Gus Greenlee and Homestead’s Cum Posey.25

But enough of the machinations of power; let’s talk business. At the Indianapolis meeting on February 15, all the league officials and some of the member teams were finalized. It was announced that Cleveland would not be able to field a team due to its inability to find a ballpark in which to play its home games. Meanwhile, Detroit’s owner John Roesink was picked as a league member with Negro League great Bingo DeMoss to manage the team. Columbus, Ohio, was also given membership, and Cincinnati was voted an associate membership “to take care of the jumps from the East to the West.”26

The unnamed columnist who wrote the Defender’s other February 25, 1933, column on the Indianapolis meeting of February 15 also reported (and editorialized) that “there was plenty talk of trades but little was actually done.”27 Although trades did occur at various Negro League meetings during the 1933-to-1962 period, it was more often the case that talk occurred without moves being made. In this case, new NNL president and Crawfords owner Greenlee could have pulled off a bombshell — he reportedly offered none other than Satchel Paige to the Nashville Elite Giants for pitcher Jim Willis but Nashville owner Tom Wilson “balked at the thought of sending this favorite of Nashville fans elsewhere.”28 As it turned out, both Paige and Willis were picked for the inaugural East-West All-Star Game that summer of 1933 although neither pitched in the game. For Paige it was the first of numerous All-Star berths, culminating in his appearance in the penultimate East-West Game on August 20, 1961; for Willis, it was his only time to be picked for the team. Clearly, Paige was in the early stages of establishing his stardom, while Jim Willis had reached his peak. For Greenlee, this was evidence supporting the baseball bromide that “the best trades are often the ones you don’t complete.”

As we shall see, more team maneuverings in and out of the fledging league were to come, presaging a 30-year history of such offseason — and inseason, at times — franchise additions and deletions. But at this formative NNL meeting, league officials Dismukes, James Taylor, and Robert Cole, owner of the Chicago American Giants, were chosen as secretary, vice chairman, and treasurer, respectively. Now permanent chairman Greenlee was still angling for an Eastern division; he reportedly met with several Eastern owners for a two-hour conference in the days prior to a final preseason “Negro National Association” meeting in Detroit on Saturday, March 11.29 According to Rollo Wilson, the uncertainty of Sunday baseball in Pennsylvania meant that schedules would not be finalized until early April but meanwhile, Greenlee was talking with Ed Bolden, John Dykes, Otto Briggs, and other Eastern club owners as well as the Baltimore Black Sox and Ben Taylor’s Baltimore Stars and the New York Black Yankees.30

The Chicago Defender’s March 18, 1933, column reported on the March 11 meeting, omitting any mention of the Eastern teams, instead recounting that club owners from teams in Indianapolis, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh (both Crawfords and Grays), Columbus, and Nashville were present and a tentative final schedule for the league’s initial weeks was announced, as well as that of the various Southern spring-training sites and some players and managers on each team. Notably, future Hall of Famers Willie Wells, Turkey Stearnes, and Mule Suttles were announced as having signed with the Chicago American Giants; speedster James “Cool Papa” Bell was retained by Gus Greenlee: and “Gentleman Dave” Malarcher, Bingo DeMoss, and possibly Clint Thomas were reportedly going to manage Chicago, Detroit, and Columbus respectively.31

According to Neil Lanctot’s seminal history of Negro League Baseball as a business institution, “a bizarre series of franchise shifts occurred soon after the outset of the season in May.”32 What it boiled down to, according to Lanctot and the black press, was that the original Detroit franchise’s unpopular white owner, John Roesink, withdrew before the season’s commencement, but after one game with weak attendance in Indianapolis, the ABCs of that city moved to Detroit but were largely replaced there by the Chicago American Giants, who, having been forced out of Schorling Park in Chicago, relocated to play at Perry Field, home of the (white) minor-league Indianapolis Indians, after playing a few games at Mills Field in Chicago that were unsuccessful financially. However, the now Indianapolis-based team still wore Chicago American Giants uniforms.33 And, to add to the confusion, in late May a seventh team, the Baltimore Black Sox, was added to the league.

There was clearly a need for a midseason meeting to sort out who was still viable to play the second half of the season. The meeting was held on June 23 at Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh. As reported in the July 8, 1933, edition of the Norfolk Journal and Guide, six of the seven teams were represented at the meeting, the glaring exception being the Homestead Grays. Neither Grays owner Cum Posey nor any other representatives of the team appeared to defend themselves against changes “involving violation of Section 7 and Section 28 of the Constitution.”34 Apparently, the membership (absent the Grays) voted unanimously to expel the Grays because they allegedly “acquired” Binder and Williams from Detroit without Detroit’s permission. This was not the only charge raised at this meeting but it was the most important and most divisive. There were other player disputes between Baltimore and Nashville and between Columbus and nonleague team, the Kansas City Monarchs. And, as befits a fledgling league still figuring out how to operate, “methods of reporting and collecting fees, advertising changes and cancellation of games preceded the work of the schedule makers.”35

The Grays were now banned from the league’s second half but the argument about who caused the rift between the league and Posey and indeed whether Posey withdrew from the league prior to being suspended was waged in the black press for weeks to come.

More importantly, the black press and Greenlee were involved in a major development for the future of Negro League Baseball — the creation of an annual All-Star game which became the signature event of Negro League Baseball. What is undisputed is that the East-West Game did not originate at a meeting of NNL owners. The story of how the game originated is disputed; bitter rivals Posey and Greenlee each placed themselves in prominent roles in its conception, but it is generally acknowledged that sportswriter Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph was the “driving force behind the game” and Bill Nunn of the Courier was instrumental in its realization; alternatively, some sources report that black Cleveland sportswriter Dave Hawkins claimed to have inspired Greenlee and Cole by staging a game in League Park, home of the Cleveland Indians, between Eastern power Pittsburgh Crawfords and Western power Chicago American Giants.36

On the eve of the 10th East-West Game, Cum Posey, in his regular Courier column called “Posey’s Points,” recounted his version of the story — that he had invited sportswriters Sparrow and Nunn to a meeting at Pittsburgh’s Loendi club to discuss an idea of Sparrow’s that “two All-Star Colored Teams feature the Annual Milk Fund Day at Yankee Stadium, New York City.” According to Posey, in the discussion “we suggested that the Milk Fund idea be forgotten and a game be staged at Yankee Stadium between the star players of the North versus the Star players of the South.”37 Supposedly, when Greenlee heard of this from Sparrow and Nunn, he changed both the venue and the name by enlisting Robert Cole of the Chicago American Giants to establish the game in Chicago’s Comiskey Park as an East-West game, with Nunn and Sparrow helping to promote it. According to historian Lanctot, Greenlee then paid for an exorbitant ($2,500) rental of Comiskey Park which was essential in making the event happen.38

On the eve of the 10th East-West Game, Cum Posey, in his regular Courier column called “Posey’s Points,” recounted his version of the story — that he had invited sportswriters Sparrow and Nunn to a meeting at Pittsburgh’s Loendi club to discuss an idea of Sparrow’s that “two All-Star Colored Teams feature the Annual Milk Fund Day at Yankee Stadium, New York City.” According to Posey, in the discussion “we suggested that the Milk Fund idea be forgotten and a game be staged at Yankee Stadium between the star players of the North versus the Star players of the South.”37 Supposedly, when Greenlee heard of this from Sparrow and Nunn, he changed both the venue and the name by enlisting Robert Cole of the Chicago American Giants to establish the game in Chicago’s Comiskey Park as an East-West game, with Nunn and Sparrow helping to promote it. According to historian Lanctot, Greenlee then paid for an exorbitant ($2,500) rental of Comiskey Park which was essential in making the event happen.38

What is particularly remarkable in Posey’s 1942 column is his parenthetical statement that Greenlee “was a very bitter baseball rival of everything and persons connected with the Homestead Grays” as he explained why Greenlee purportedly changed the game’s name and venue.39 Was the Posey of 1942 also remembering nine years later that Greenlee as NNL chairman banned the Grays from participating in the second half of the 1933 NNL around the same time of the conception of the East-West Game? In a July 8, 1933, letter published in the Courier, Posey claimed that rather than being expelled from the NNL, the Grays had withdrawn from the league because President Greenlee restricted league teams to getting 35 percent of gross receipts for league games, with 5 percent going to the league, when Posey had never accepted less than 40 percent.40

In a column headlined “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs” appearing in the Courier a month after the just-mentioned letter, Posey expanded his charges against the league, now stating, “[W]e came out of the Negro National Association because it was not a fair league and was handled to a great extent under the sinister influence of the booking agent of the East. All we need at the head of an association of colored baseball clubs is a man with courage enough to fight for what is due the owners of colored clubs.”41 Posey was now contending that booking agents Nat Strong and Ed Gottlieb were strong-arming his team and others by insisting on 5 percent of the receipts of any league game between Eastern and Western clubs (Gottlieb) and blocking games from being played at Yankee Stadium (Strong). Posey obliquely alleged that these actions not only benefited Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords but also by extension the Columbus Blue Birds and Baltimore Black Sox, who stopped playing league contests and booked games independently in the second half of 1933.42

So what really happened at the league’s June 23 business meeting at Greenlee Field? One firsthand account by a participant in that meeting was reported. After Dizzy Dismukes relinquished the NNL secretary’s job to manage Columbus, John L. Clark took that position. Admittedly not an objective observer, as he was a Crawfords official as well, Clark nonetheless provided a detailed description of how and why the league expelled Posey while meeting at “Greenlee’s Gardens.” Clark charged that Posey’s “case” was a subterfuge for his intention to a) appropriate players directly rather than legitimately acquire them from other league clubs and b) cancel league contests without notice.43 It is a minor point, but still worth mentioning, that Clark explains why the meeting was held at Greenlee Field, arguably enemy territory for Posey, rather than a more neutral site. According to Clark, the meeting was originally scheduled for 10 A.M. at Center Avenue YMCA but was changed to 1:30 P.M. at the offices at Greenlee Field because several league members were not able to reach the city for the earlier scheduled time and location. In addition, Clark carefully documented that the meeting was not a “special session to pass decision of an unfaithful member” — rather, it was called primarily to draft a schedule for the season’s second half and before charges were telegraphed by Greenlee to Posey on June 21 that Posey had taken players Binder and Williams without permission from or compensation given to Detroit. Clark further states that Posey had been requested to attend, but after five other items of business were taken care of, Posey’s actions were deliberated without his presence. It was then contended by Chicago at the meeting that Posey had canceled upcoming scheduled league games with them on June 24-26 at Greenlee Field and that his actions were eroding the goodwill of the public.

In Clark’s account, after a unanimous vote to expel the Grays at the June 23, 1933, meeting, Posey did appear but failed to satisfactorily explain his actions and evaded direct questions. Clark editorialized that Posey was against league play largely because he did not control the league. But Clark did present the argument that Posey left for financial reasons, with league-mandated player and salary limits having “a great deal to do with Posey’s kidnapping of Binder and Williams.”44

Whether one chooses to believe Posey’s version or that of Clark (or a little of both), any observer, contemporary or in retrospect, should realize that a pattern had been established. Not only would Posey and Greenlee largely remain at loggerheads, but fierce battles, with accusations of league violations and decisions to expel teams and/or for teams to declare that they were abandoning the league schedule, would be common throughout the 30 seasons of Negro League play starting in 1933 and ending in 1962. Although there were certainly such issues (and many others) in the prior incarnation of the NNL, league President Rube Foster was such a powerful and revered figure that his rulings tended to be respected and followed. There are many reminiscences in the black press about the “halcyon days” of the 1920s and the founding fathers of league play, indicating that many scribes found the ongoing ownership battles in the successor leagues to be tiresome, divisive, and destructive not only to league operations and league success, but also to the larger cause of promoting black athletics with an eye toward eventual integration into white major league operations.45

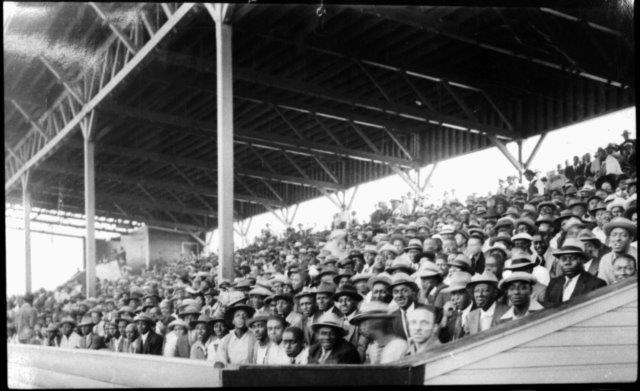

In the final analysis, the 1933 NNL season was a limited success. Only three teams — Nashville, Chicago/Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh — completed the entire season. The first East-West All-Star Game was played with the West prevailing, 11-7, but seven of the 14 who played for the East were from the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and seven of the nine West players were from the Chicago American Giants. Attendance for the game has been variously reported as 19,568 and about 12,000, a pretty good turnout for the times and for a league limping along to the end of its inaugural season, but far less than several future East-West Games.46

Not only did the Homestead Grays, Columbus Blue Birds, Detroit Stars, and Baltimore Black Sox abandon (or in the case of the Grays, were also suspended from) league play, but top teams like the Kansas City Monarchs, the Philadelphia Stars, the New York Black Yankees, the Newark Browns, and the New York Cubans never joined the league. Additionally, there was a short-time member of the 1933 NNL, mostly in the season’s second half, called the Akron Black Tyrites, who were 2-9 in league play.47 Chicago protested a game played against Baltimore and when the protest was upheld, they won the league’s first half by one game.48 The second half was apparently a muddle — down to only three teams, Chicago was eliminated as a second-half contender as a compromise resulting from confusing and competing claims by Nashville and Pittsburgh regarding games each wanted counted in their favor as forfeits by disbanding teams. According to the September 27 edition of the New York Amsterdam News, Nashville and Pittsburgh were to play a five-game series, and the winner of that series would play Chicago for the 1933 league championship. This author has found no mention of any of those preliminary or championship games being played.

There was hope, though, for 1934. Even in Cum Posey’s “Pointed Paragraphs” of August 12 in which he lambasted the NNL’s white booking agents while he indicated that a stronger league leader than Greenlee was needed, Posey stated, “Colored baseball in 1934 will start on the upturn.”49 And Rollo Wilson, while noting that in his opinion the booking agents were against league baseball, seemed to believe that in 1934 the NNL would succeed where it failed in 1933 with a new alignment, including Eastern teams in New York and Philadelphia. “Next year,” Wilson said, “always brings something new and better to some few….”50 Which “few” would they be?

1934

At the end of 1933, it was hardly clear whether the wind was blowing in the direction of an established NNL that would continue operations in 1934 and beyond, or back toward an array of independent clubs like the Monarchs, Grays, and Philadelphia Stars and loose confederations like the NSL existing in an uncertain black baseball universe. After all, recent history involved aborted one-year leagues — the ANL and the E-W League did not survive beyond 1929 and 1932 respectively. Given the way the 1933 NNL season petered out, with only three of seven clubs finishing the season and no apparent postseason playoffs, what indications were there of a sustained NNL?

On the one hand, you had a successful start of an all-star franchise in the inaugural East-West Game; on the other hand, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that the Nashville Elite Giants, Chicago American Giants, and Pittsburgh Crawfords had very little communication between them during early winter of 1933-34.51 According to the Courier, it was believed that the NSL would operate in 1934 but it was unclear whether that three-team NNL nucleus could join with other Eastern clubs and/or Western clubs to form a circuit, while it was doubtful that all three regions would form a complete confederation. The “moguls” behind all the clubs were operating in secrecy, but it was at least known that a January 13, 1934, meeting in Pittsburgh was planned. The invitation list constituted 12 teams from the East, West, and South which did not even include the Homestead Grays and representatives of Dayton, Columbus, Indianapolis, and Akron.52

The turnout was limited to Cum Posey, who was not formally invited but received an oral notification from Chairman and fierce rival Greenlee, and apparently, Greenlee himself and Prentice Byrd of the Cleveland Red Sox attending.53 The 1933 league secretary (and Crawfords employee) John Clark called this meeting discouraging, as the lack of turnout indicated a desire by most potential league members to wait and see what developed.54 Posey, on the other hand, seemed to think that the league had potential if Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Newark, who had their own parks and who had owners with experience in Ed Bolden (Philadelphia), Joe Cambria (Baltimore), and Harry Passon (Bacharach Giants, formerly of Atlantic City but now playing in Philadelphia), could be included in the league. Otherwise, Posey planned for the Grays to continue the independent status they assumed when they were expelled in the second half of the 1933 season.55

Most importantly, however, Greenlee declared at the January meeting that there would be a subsequent league meeting on February 10 in Philadelphia. At the February meeting, six clubs attained full membership in a planned 1934 league — the three-team nucleus of 1933, the Cleveland Red Sox, Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars, and the Newark Dodgers. Bolden objected to there being another Philadelphia team in the league (Passon’s Bacharachs), believing that he could not succeed with intracity league competition, and his wishes were granted. He did not succeed, however, in convincing the other owners that a good-faith financial deposit (also called a franchise fee or forfeit) was unneeded. Meanwhile, neither the Grays nor Cambria’s Baltimore Black Sox were admitted to the league, in the latter case because he did not attend this meeting.56

Although little of substance was accomplished at the February 10 meeting, two important steps were taken — 1) a third league meeting was announced for March in Philadelphia at which a schedule of playing dates was to be decided upon; and 2) 1933 Chairman Greenlee requested that Rollo Wilson operate as chair when the new league members were voted on.57

On March 10 and 11, the newly reconstituted league did in fact meet and chose Courier writer Wilson to be the commissioner of the NNL, although Greenlee was still voted chairman of the board, with Tom Wilson, owner of the Elite Giants, as vice chairman, John Clark as secretary, and Robert Cole as treasurer. According to sportswriter Randy Dixon, the choice of Wilson to head the league deserved high praise, as Dixon believed that Rollo had stellar credentials: “His long experience as a critic and follower of colored baseball, his keen insight of the game, and his wide acquaintanceship and contacts makes him ideally suited to the position.”58 Author Neil Lanctot indicated that it was commonly viewed that Wilson, who was an experienced operative from prior Negro Leagues and who was seen as impartial, could successfully arbitrate league disputes and counteract perceived bias in Gus Greenlee’s 1933 league operation.59

— New York Amsterdam News, March 17, 1934

And disputes there were — immediately, Wilson became the judge of conflicts between the Homestead Grays (who were made associate members at the March meeting) and the Pittsburgh Crawfords over outfielder Vic Harris and catcher-infielder Leroy Morney, while pitcher Ted Trent was claimed by Chicago and the New York Black Yankees (who were still being debated as potential associate members). Meanwhile, at the meeting a schedule was adopted, with the season to be split into halves — the first half to be played from May 12 through July 4, and the second half ending September 9, to be followed by a playoff between the winners of each half-season. And the Negro Southern League, represented by Nashville owner Tom Wilson at this meeting, agreed to be a farm system for the NNL as NNL clubs could buy NSL players “on a trial basis” with the player chosen returning to the NSL club if he did not succeed in the higher league.

The final preseason meeting of 1934 was held in Pittsburgh on April 14. Along with routine business (booking issues, forfeit fees, authority for disbursements granted to league Secretary Clark), the few members present witnessed “representative” Nat Strong withdraw the application of the New York Black Yankees for membership and rejected Baltimore’s application as they again did not appear at the meeting.60

But Cumberland Posey was not satisfied with his team’s associate status. He still chafed about not being officially invited to the initial 1934 meeting, and he also was greatly dissatisfied with the league’s decision not to offer Harry Passon’s Bacharach Giants league membership.61 League secretary Clark used his Courier column to answer Posey’s “points” pointedly and at times, sarcastically. Clark simply said that Posey was left off the initial invitation list because of his actions giving rise to his team’s expulsion in mid-1933 and that his other claims to players and criticisms of league choices on membership and on other matters did not merit equal consideration with opinions of full league members. Perhaps the league’s biggest mistake, Clark sarcastically opined, was not picking Posey to be league commissioner, as “everybody has been ‘picking’ on the Homesteader ever since.”62

Was it true, as Clark claimed, that Posey wanted that “his every claim should be honored, his views accepted without modification”?63 Not according to Posey. In his view, the well-intentioned commissioner Wilson was being undermined by the power-hungry league secretary Clark, who, he believed, had no right to decide matters like disputed playing dates between clubs or even whether an associate member like the Grays had as much right to consideration as did a full member. Meanwhile, his rival Greenlee was being “strong-armed” by Nat Strong, white booking agent and part-owner behind the scenes; African-American James Semler was the public franchise representative of the New York Black Yankees.64 The result, according to Posey, was a league without monthly financial reports and an independent commissioner who could not stop the Crawfords from operating the league in their own best interests. 65

Despite all the vitriol, the league finished its first half without losing any members. And, in a midseason meeting held in Philadelphia on June 28 and 29, right before the first half ended, the league expanded, adding the Bacharach Giants and Baltimore Sox as full members for the league’s second half. Commissioner Wilson, in his June 30, 1934 Pittsburgh Courier column, indicated that the main order of business at this meeting was to settle on a second-half schedule but that “certain warring owners” would need to peacefully settle their disputes.66 Settlement of the main battle, between Posey and Greenlee, was not going to come easily. During the meeting, Posey’s “money man [and numbers man]” Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson, turned down an opportunity for full membership for the Grays that was ostensibly offered by the other teams. Secretary Clark, in his July 14 Courier column stated that Commissioner Wilson put membership discussions ahead of the “regular order of business” to bring about harmony and to “perpetuate organized policies in Negro baseball.”

In the end, according to Clark, Jackson turned down membership while his co-owner Posey’s agenda — which, of course, included removing columnist Clark from his league secretary position — was turned down flat by the league.67 Nevertheless, both the Atlanta Daily World and the Chicago Defender gave mostly positive reports of this meeting and the status of the league. The World characterized the meetings as “for the most part, amicable with the owners disposed to give and take.”68 Meanwhile, the Defender opined that “although the league machinery has not operated smoothly, it is a distinct improvement over performances of 1933.”69 Arguably, Posey’s repeat performance was no worse and perhaps less disruptive to league operations than that of 1933; and adding rather than subtracting teams constituted distinct progress.

Pittsburgh racketeer Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson (at right) provided Grays’ owner Cum Posey with the money he needed to lure many of the Negro Leagues’ best players to Homestead in the 1930s and 1940s. (Noir-Tech Research, Inc.)

The second half of the 1934 season had its fair share of successes, failures, and ultimately, disputes. The second East-West Game followed up successfully from the first one in 1933 with over 25,000 fans, up considerably from the attendance at the inaugural event, seeing East defeat West by a 1-0 score.70 The league also staged a four-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium on September 9 before over 20,000 fans, with the Chicago American Giants defeating the New York Black Yankees 4-3 in the first contest and Satchel Paige dueling Stuart “Slim” Jones to a 1-1 tie in the second game.71 The American Giants, first-half pennant winner, played the second-half pennant-winning Philadelphia Stars for the league championship. The seven-game series, which ended with the Stars winning 2-0 in Game Seven to take the Series four games to three, was marred by a series of protests, with Chicago saying that Hall of Famer Jud “Boojum” Wilson should have been ejected from Game Six for striking umpire Bert Gholston, and both teams protesting Game Seven.72

Nevertheless, columnist Ed Harris of the Philadelphia Tribune generally praised the league for its two “spectacles of sufficient proportion” (the Yankee Stadium doubleheader and the East-West Game) while noting that the league’s biggest challenge was that it needed to book nonleague games to maintain its profitability, thereby undermining the integrity of the league schedule.73 And columnist Romeo Dougherty of the New York Amsterdam News praised Greenlee for his successes in staging games in New York while suggesting that the best future path for the league would be to add two New York teams and form an Eastern association with Greenlee as president and have a Western association based in Chicago, with the league champions playing each other at the season’s end for a national championship. The ambivalent fortunes of the league are captured well by Dougherty’s statement near the end of his column that he was “looking forward with anxiety (emphasis added) to the meeting of the National Negro Baseball League in January.74

Before that January 1935 meeting, however, the league had one final abortive session in 1934. In it, only league treasurer and Chicago owner Robert Cole, Chairman Greenlee, and Posey and Jackson of ineligible-to-vote associate member Homestead appeared. The meeting was supposed to resolve the Game Seven protest as well as have members pay off their league obligations. When 5 o’clock came and went without any other members appearing, Greenlee expressed the opinion that league business could be conducted, including bill payments. Treasurer Cole refused to “sign a single check until all members were present — adding that there were several matters that he wanted to be clear on.” Clearly, Cole was dissatisfied about the failure of his league to rule on his team’s protest — and eventually, the protests by both teams were thrown out and the Stars were awarded the 1934 league championship.75

1935

Although 1934 was a successful year compared with 1933, NNL Commissioner (but not for long) Rollo Wilson admitted that “few, if any clubs made any money” while Chairman Greenlee cautioned that “in spite of the success of 1934, we have not arrived.”76

One potentially lucrative opportunity beckoned. Although the NNL played two successful doubleheaders at Yankee Stadium in September of 1934, the second one interrupting the league championship series, they did not have any New York area teams represented in the 1934 NNL.77 According to Neil Lanctot, NNL Chairman Greenlee realized that the Eastern market provided better moneymaking opportunities than did the Midwestern ones, in large part because of the sizable black population in the Washington-New York corridor.78 In addition, the Atlanta Daily World, in reporting on the upcoming initial 1935 meeting of the NNL on January 12, stated simply that Eastern clubs were reluctant to play in the West because “they almost lost their shirts when they made Western trips last year.”79

But there was a potential roadblock in Nat Strong, the white powerhouse in the world of black and semipro baseball in New York City. Strong ran a booking agency which had a virtual monopoly on the New York baseball booking business, charging 5 to 10 percent of the gate receipts to book games in venues like Yankee Stadium and Ebbets Field while offering minimal ($500-$600) flat guarantees to black teams that played Sunday night games at Brooklyn’s Dexter Park.80 Though it was clear that Strong would oppose it, the NNL nonetheless voted in November 1934 to add the Brooklyn Eagles to the 1935 NNL mix. The Eagles, owned by Abe and Effa Manley, were to play at Ebbets Field, thereby competing directly with games that Strong would book at Dexter Park.81

Suddenly and unexpectedly, that potential problem disappeared, and an even greater opportunity to expand into the New York market became viable because Nat Strong died of a heart attack on January 10. When the NNL met in New York shortly after Strong’s death, the league voted to admit not only the Eagles but also the New York Cubans, owned by Cuban-American Harlem racketeer Alejandro “Alex” Pompez. The league was now a robust eight-team assemblage; in addition to the Eagles and the Cubans, the Homestead Grays were bumped up from associate to full membership, and Nashville, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Newark fielded teams as well.82

Suddenly and unexpectedly, that potential problem disappeared, and an even greater opportunity to expand into the New York market became viable because Nat Strong died of a heart attack on January 10. When the NNL met in New York shortly after Strong’s death, the league voted to admit not only the Eagles but also the New York Cubans, owned by Cuban-American Harlem racketeer Alejandro “Alex” Pompez. The league was now a robust eight-team assemblage; in addition to the Eagles and the Cubans, the Homestead Grays were bumped up from associate to full membership, and Nashville, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Newark fielded teams as well.82

The January 12 meeting could be characterized as celebratory, even though the proceedings were “chilled a bit through the death of Nat Strong.83 While the league members voted unanimously to include the Cubans, they also dropped the Baltimore and Cleveland teams from the roster. Pompez then spoke, “declaring himself ready to spend $35,000 to make New York baseball-conscious as far as Negro baseball is concerned,” with plans for enlarging and improving Dyckman Oval in Upper Manhattan as the Cubans’ home venue. In addition to perfunctory league business such as Secretary Clark’s 1934 report and scheduling and player salary discussions, there was a radio broadcast Saturday afternoon and a dinner for over 100 people at Harlem’s Small’s Paradise on Saturday night, with a concluding session for player transactions Sunday afternoon.84

— Atlanta Daily World, January 23, 1935

The league got down to business in a three-day confab held in Philadelphia from March 8 to 10. The league’s managers chose eight umpires out of 24 applicants for the 1935 season, including the umpires who worked the protested games of the 1934 league championship. They also submitted their player lists, with only a couple of players being claimed by more than one club, meaning that player disputes were at a minimum. As usual, a great deal of time and energy was devoted to scheduling, characterized by Cum Posey in his March 16, 1935, Courier column as “a matter of give and take all the way with a desire shown by all the members to aid the new clubs in their home cities.”85

The bombshell revelation of this meeting, however, occurred on Sunday night when it was revealed that 1934 Commissioner Rollo Wilson was voted down for the 1935 post; instead Ferdinand Q. Morton — the first black person chosen to be a New York City Civil Service commissioner — was chosen to succeed Wilson.86 The choice was not unanimous, as Greenlee and Philadelphia Stars owner Ed Bolden still supported Wilson — but Robert Cole, still bitter about the controversial resolution of the 1934 league championship protests in favor of the Stars, and frequent Wilson (and Greenlee) critic Cum Posey joined the two New York teams in supporting Morton.87 All the other 1934 league officials, including Chairman Greenlee, were re-elected.

Also at this meeting, it was finally resolved that the 1935 lineup of teams would not include the Bacharach Giants (who had attended the January 12 meeting) and would therefore have eight teams, as the “surprise of the meeting was the inability of the Bacharach Giants of Philadelphia to post the necessary forfeit.”88 All the other teams posted the necessary $500 forfeit, or franchise fee, a perhaps small but yet significant indicator of a newly established financial stability for the league.89

And then it all unraveled. This author has found no mention in the black press or in several secondary sources of any formal league meetings during the 1935 season, although presumably some contact between owners happened as traditionally the schedule for the league’s second half would have been arranged during the season. But, according to Ed Bolden, the league was in conflict. Bolden was quoted in the Amsterdam News of August 31 as follows: “There is too much politics in the league and we are dissatisfied with the way its business has been conducted. … We intend to have a show-down at the fall meeting and rip things wide open.”90 Unfortunately for Bolden, the league did not hold any fall meeting, even though Cum Posey pleaded for a meeting “so things could be ironed out.”91 Posey and the other owners clamored for the return of their $500 forfeits while various league owners, including Gus Greenlee and new owners Pompez of the Cubans and the Manleys of the Eagles experienced financial problems, in whole or in part due to poor league attendance.”92 The Cubans were successful on the field, winning the league’s second-half pennant but losing to first-half winner Pittsburgh in an exciting seven-game championship series.93 Yet despite the successful postseason series, the future of the second NNL seemed to hang in the balance.

The 1936 Pittsburgh Crawfords traveled in style thanks to owner Gus Greenlee. (Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

1936

In the early days of 1936, Commissioner Morton called for a league meeting on January 10. Chairman Greenlee, however, was not planning to attend this meeting, and in the end it was not held. Since the nonmeeting followed the disarray and dissension of most of 1935, a fair characterization of the status of the league would be “in limbo” at best. Greenlee did finally call for a meeting that was held in Philadelphia on January 26 and 27. According to Courtney Smith’s article covering the Philadelphia Tribune’s reportage on the Philadelphia Stars from 1933-1938, Tribune writer Ed Harris was one of seven writers who attended but were barred from this meeting. In a January 16, 1936, Tribune article, Harris expressed surprise that the NNL moguls did not realize that canceling league meetings as they did on January 10 undermined the league’s legitimacy. Now Harris expressed a belief that ownership’s blocking of press coverage of league operations left the fans lacking information about the league and was a foolish way to alienate the fan base.94

Since media could not therefore provide an unfiltered report of the meeting, the fans got a measure of the current league plans that was part conjecture, part observation of the comings and goings of prominent individuals, and part leaked information along with some apparently announced league determinations. Conjecture – there is rampant displeasure with the current slate of league officers, including the commissioner: “[A] clean sweep in the personnel officers is forecast.” Observation – Greenlee left the meeting early, at the end of the first day, and then switched places with Secretary Clark, who missed day one. Commissioner Morton stayed away on Saturday “but gave them a very limited amount of his time on Sunday.” Leaked information – unofficial word that Greenlee offered his resignation as chairman to Commissioner Morton while “varied opinions on the financial health of the body leaked out to the pressmen.” Apparent announcements – Newark Dodgers owner Charles Tyler sold his team to heretofore Brooklyn Eagles owner Abe Manley, while Manley’s Brooklyn Eagles were “thrown back into the lap of the parent body” and New York Black Yankees owner James Semler applied formally for membership but the league deferred a vote until a planned March 7 meeting. Conclusion? “Members of the Negro National League deferred until March 7 many important matters which intrigue the diamond fans of the country.”95

Echoing Harris, this was no way to engage the willing but often impoverished black fan base. So Candy Jim Taylor, manager of the Nashville (soon to be Washington) Elite Giants, spoke out. In a February 15, 1936, Defender column Candy Jim criticized the magnates: “[A]fter waiting all winter to call the meeting there was little done to get the clubs together and to get the fans interested.”96 Taylor felt that many leaders of black baseball from its earlier days were missed — some like former manager C.I. Taylor, his older brother, and Rube Foster, had since passed away, but others like J.L. Wilkinson, owner of the independent Kansas City Monarchs, and St. Louis Stars owners Dick Kent, L.A. Brown, and G.B. Key, he thought should be invited to a general baseball conference. Finally, Candy Jim raised a sore point that would continue to be harped on throughout the history of Negro League operations: he suggested that the NNL pick a non-owner of a club, perhaps a sportswriter, as league president, pay him a salary and expect him to use his connections to publicize the game.97 But why should the wise ownership of NNL franchises follow such eminently good advice?

— Chicago Defender, February 15, 1936

Instead, the Defender reported in its February 29, 1936, edition that Chairman Greenlee would reconsider his resignation and remain NNL president.98 But they were wrong. At the March 7-8 meeting, Greenlee did indeed resign as president and “Chief” Ed Bolden was chosen to replace him. Commissioner Morton was retained for another year. But Abe Manley was chosen as vice president, with former VP Tom Wilson shifting to treasurer, replacing Robert Cole, who had remained league treasurer in 1935 even though he sold his interest in Chicago in mid-1935. Since new American Giants owner Horace Hall kept them independent in 1936, it clearly made no sense for Cole, no longer even affiliated with a team no longer in the league, to remain as treasurer — after all, officials outside of team employees were rarely involved in league operations! John Clark continued as league secretary.

Other decisions made at the March 7-8 parley included rejecting the Black Yankees’ membership application, a determination to play another split-season schedule with a seven-game championship playoff between the winners of each half, and allowing Nashville to shift its operations to Washington and play at Griffith Stadium, the home park of the Washington Senators, while the now renamed and shifted Brooklyn Eagles would play in Newark’s Ruppert Stadium as the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays would play at Forbes Field, home of the National League Pirates.99

On June 18, 1936, the NNL held a midseason meeting in New York. The meeting followed private ones held between the now (Nat) Strong-less but still strong and independent Black Yankees, represented by African-American owner James Semler and white owner/booking agent William Leuschner (former partner of Nat Strong), and Commissioner Morton, in which the Yankees were persuaded to drop damage suits against Eagles owner Abe Manley and New York Cubans owner Alex Pompez for using players under contract to the Yankees. In the subsequent league meeting, the Yankees, “stormy petrels of Negro baseball,” were finally made a full member of the league.100 This meant that, for the second half of the 1936 schedule, the league would have seven teams, with the Yankees joining the Nashville/Washington Elite Giants, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Homestead Grays, Philadelphia Stars, Newark Eagles, and New York Cubans in league competition.101

While mundane league business was also conducted at the June 18 meeting, including continuing the Worth baseball as the official NNL baseball, coming to terms with league umpires, and acknowledging a Homestead Grays protest of a May 24 game in Newark, the real league action was elsewhere. Though Greenlee was out as league chairman, Cum Posey was still at odds with him and league Secretary Clark. Posey refused to play his home games at Greenlee Field, resulting in no Grays-Crawfords contests during the league’s first half. Meanwhile, a ruling that each league team had to play the others five times per half led to a dispute over the winner of the first-half pennant. In the end, the Elite Giants were declared first-half winner over the Philadelphia Stars but a “convoluted controversy” over rescheduling two Stars-Elites games was unsatisfactorily handled by Commissioner Morton.102

While the first-half controversy raged on, the Crawfords claimed the league’s second-half crown. But the planned league championship series was canceled after the playing of only one game. A suggestion that the series be finished in the spring of 1937 was dismissed; meanwhile, Chairman Bolden expressed the opinion that “it is not mandatory that the two champions complete a World Series if it does not pay financially.”103 Not only does this statement of Bolden’s indicate that the league’s disordered and disputed affairs affected fan interest, he preceded it in his Defender column by an even more disturbing statement: “[I]t is news to me that the Negro World Series has been abandoned.”104 Did Bolden really not know what was going on in the league over which he presided?

1937

At the start of 1937, the NNL was in trouble. Philadelphia Tribune writer Ed Harris, a particularly strident league critic, had assessed the league thusly: “The league as a league is a flop. It seems that some of the teams in the group are in it the way some people are married — simply because it sounds nice.”105 And the marriage was fractious — according to Posey, the seven members of the league as 1936 ended were arrayed as follows: three pulling one way and four pulling opposite.”106

In addition, they would soon have Western competition. In early October of 1936, a “Negro Western League” had an organizing meeting in Indianapolis, with attendees choosing Major Robert R. Jackson as league head, Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson as treasurer, and Chicago Defender sports editor Al Monroe as secretary. Eight cities were awarded league membership at this meeting: Kansas City, Chicago, Indianapolis, Memphis, Birmingham, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Detroit.107

A second meeting was held in Chicago in early December where the league officials were formally installed, a scheduling committee was formed, and statements were made indicating that players who had gone East to play for 1936 NNL teams would be returned to their rightful Western owners in time to prepare for the coming 1937 inaugural “Negro National League.”108 Was the Defender simply mistaken in labeling this new venture as a new “NNL,” or were they expecting the 1936 NNL to cease operations — or were they harkening back to the original Western-based NNL of the 1920s by calling this new league the NNL and perhaps planning to refer to whatever Eastern association that continued in 1937 as the Negro National Association?

Despite its sagging fortunes, the NNL (Eastern variety) did hold a meeting on January 4, 1937, in Philadelphia. It was reported in one source that the NNL clubs were considering adding yet another New York club to the league, and were also interested in connecting with the nascent Western league, but neither of those initiatives would occur in 1937.109 Instead, the meeting “produced little action for the Negro National League,” reported embattled Secretary Clark.110 Clark was himself taking action by declaring his resignation as league secretary effective at the end of January. Clearly, Posey’s criticism of Clark’s “double-dealing” (working for the league and the Crawfords simultaneously) had taken its toll, though why a secretary should be more unbiased than the other league officials, many of whom owned or worked for teams, remains puzzling.

Announcements involving the Grays, Crawfords, Cubans, and Black Yankees provided some hope that the most bitter disputes were abating, as the Grays said they would play 1937 games at Greenlee Field and the Black Yanks at Dyckman Oval, the home field of the Cubans. Additional news from the January 4 meeting included the announcement of a minimum ticket price of 35 cents for all league games, and that Commissioner Morton was running unopposed for another term and was simultaneously running for league chairman against Courier business manager Ira Lewis.111

A quick follow-up meeting in New York in late January decided the league officers for 1937. Commissioner Morton stayed on for a third term; instead of Ira Lewis, Leonard Williams, a reputed Pittsburgh underworld figure, was chosen chairman, with Elites owner and 1936 Treasurer Tom Wilson returning to the vice-chair position he held in 1934 and 1935 and Abe Manley, who had been vice chair in 1936, switching with Wilson and becoming treasurer. An important change from prior years (albeit one that was later rescinded) was the decision to play an undivided season from May 15 through September 15 — could this be an attempt to avoid another controversy like the previous year’s dispute over the first-half winner? Various player trades were discussed, with some rejected and others still pending. Finally, what the Pittsburgh Courier described as a highlight of the meeting was a unanimous vote by the members to be covered by the Major-Minor agreement of Organized (white) Baseball. Baseball integration was not even a rumor at this point, but acquiring legitimacy by operating under the same structure as white baseball was a desperate hope of the struggling league.112

The NNL held its annual schedule-making meeting in New York in late March, a three-day affair punctuated by a blockbuster trade: The Crawfords sent legendary slugging catcher Josh Gibson and star third baseman Judy Johnson to their rival Homestead Grays for catcher Pepper Bassett, third baseman Henry Spearman, and $2,500, then sold pitcher Harry Kincannon to the Black Yankees for an undisclosed amount.113 Superficially, the first deal was an equal exchange of players at two positions, but the cash element augmenting the meager return of talent for two future Hall of Fame players along with the sale of Kincannon demonstrated that Greenlee was in dire need of funds. Meanwhile, with Leonard Williams having declined the chairman/president position, the league returned the Crawfords owner to his former position.114

During the 1937 season, two major developments threatened the league’s viability. First, New York Cubans owner Alex Pompez had to leave the country to avoid arrest for his prior involvements in New York’s numbers rackets. While Pompez cooled his heels in Mexico City, he left Roy Sparrow and Frank Forbes in charge of his franchise.115 At the same time, Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo commenced his raids on prominent Negro League players including luminaries Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, and player-manager Martin Dihigo of the New York Cubans. Eventually, 18 Negro League players, many of them from the Crawfords and the Cubans, departed for the Dominican Republic in 1937, and by April, it was announced in the New York Age that the New York Cubans would not play ball in 1937, leaving the 1937 NNL as a six-team operation.116

The NNL did try to take action to either recover the Dominican jumpers or at least punish them and suspend them from the NNL for their actions, while gaining US government support in sanctioning the Dominican Republic. In its June 19, 1937, issue, the New York Amsterdam News reported that the NNL held a meeting in Philadelphia on May 27 for the purpose of condemning the raid of their players and to strategize about enlisting US government support in their efforts to get these players to return.117 Several NNL officials and Negro American League President R.R. Jackson did indeed meet with a State Department official, leading to a fruitless discussion with an emissary of the Dominican government, and the players did not return to the NNL in 1937.118

Meanwhile, the newly organized Negro American League (as it was now referred to by the Chicago Defender) met in late February of 1937 with its primary purpose being to prepare the league’s schedule. The NAL planned a split season and a playoff between winners of its first and second halves. To show that the NAL was for real, league President Jackson “ordered all clubs to post forfeit money to guarantee good faith and to assure the fans that no combats will be canceled at any time.”119 At the meeting, the NAL announced that Ted “Double-Duty” Radcliffe had been traded to Cincinnati by Indianapolis and hurler Thomas had been sent by Chicago to Detroit for an “infielder yet to be selected.”120 The NAL completed its 1937 season with a five-game series between Chicago and Kansas City to settle a tie in the standings of the league’s first half. Kansas City won the playoff, which included a 17-inning tie, in the second game, and the league decided that there was no purpose to having another playoff series, as the Monarchs had won the season’s second half.121

Despite the suggestion mentioned at an early 1937 NNL meeting of maintaining contact with the NAL, the two leagues had player disputes and therefore did not develop much of a working relationship in 1937.122 The Monarchs, though, did play a nine-game series against a team of NNL pennant-winning Homestead Grays and second-place (in the season’s first half) Newark Eagles players, with the Grays/Eagles taking seven of the nine games.123 As Defender writer Frank “Fay” Young editorialized, “I cannot see where it can be called a World Series.”124 NNL President Greenlee chimed in by saying that the games were merely a promotion staged by the owners of the Newark Eagles and Homestead Grays and therefore not sanctioned by the NNL.125 Nevertheless, the series signified the beginnings of interleague competition at the end of the first year of a fledgling two-league black institution.

While the “World Series” was being played, the NNL held a final 1937 meeting in New York on September 27. Former NNL Secretary Clark characterized this meeting as of little moment. Clearly, ownership battles were evident. Clark reported charges being made by Posey and others that Greenlee refused to allow the Dominican contingent of NNL players to return to the NNL and also used some of these players himself in unofficial 1937 games.126 Would Greenlee be allowed to continue to lead the NNL in 1938?

Buck Leonard tries to beat the throw to first base in a 1937 Negro National League game between the Homestead Grays and Philadelphia Stars. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

1938

As the year started, the NNL was on very shaky footing. According to historian Lanctot, “[B]y 1938 numerous African-American sportswriters, owners, players and fans had begun to doubt whether professional black baseball could ever fulfill its potential as a profitable enterprise.”127 Not only were the conditions of a continuing depression depressing fan turnout, but the weak financial conditions and limited business acumen of most NNL franchises also contributed toward maintaining a state of constant trouble in the league’s attempt to remain viable. Figurehead Commissioner Morton called for the first 1938 NNL meeting to be held in New York in mid-January but, according to the Pittsburgh Courier, no one showed up. At least Greenlee could still get ownership to meet, which they did on January 28 and 29. In anticipation of the gathering, Greenlee maintained that the league, its teams and its players needed to operate in a more disciplined fashion, and salaries, which he claimed to be two-thirds of operating costs for the league’s first five years, needed to be reduced.128

— Pittsburgh Courier, January 29, 1938

In the business files of Effa Manley, a document summarizing this January meeting was found. Following up on Greenlee’s concerns, the six teams expected to form the 1938 NNL — Effa and Abe Manley’s Newark Eagles, the New York Black Yankees, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, the Homestead Grays, the Elite Giants (who were in flux as to their location — which would explain the missing city next to their name), and the Philadelphia Stars were listed underneath a statement that “for the past seven years, Negro League Baseball has operated at a loss.”129 The document went on to declare that salaries would have to be cut so that even greater losses would not occur in 1938.130

But this agreement aside, the league was still seen as fundamentally divided: “[T]he Nashville [Elite Giants] Philadelphia, Pittsburgh Crawfords were aligned against Newark, Black Yanks, and Homestead Grays.”131 Not only the Defender, but the other leading black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, perceived the ongoing conflict, describing it as “petty quarreling, underhanded moves, factional fights and differences, and failure to meet obligations.”132 The NNL responded by electing a three-member board of Greenlee, Abe Manley and Thomas Wilson to head the league, and picked Cum Posey as secretary-treasurer. It was an attempt to bridge the gap between sides by picking two owners from each faction as league officials. In addition, the league declared efforts to reduce expenses other than salaries such as cutting down from six to three traveling umpires and attempting to eliminate the expense of middlemen by clubs doing their own promotions.133

On March 6 and 7, a final preseason NNL meeting was held in Philadelphia. Resolved — the league would consist of seven teams, including a new team in Washington called the Black Senators.134 Postponed — the appointment of a commissioner to preside over both the NNL and the NAL. The NAL had picked a commissioner, their 1937 Chairman R.R. Jackson, at an earlier NAL meeting held in Chicago on Saturday, February 19 and had sent J.B. Martin of the Memphis club to Philadelphia to nominate Jackson to oversee the operations of both leagues.135 After a heated debate, however, there was a deadlock in the NNL vote for commissioner between Jackson and Judge Joseph Rainey of Philadelphia. It had already been made clear that NNL Commissioner Morton was not under consideration for the job. There were many player sales and trades at this meeting, most notably involving pitcher Chet Brewer being sent to Washington from Pittsburgh and Judy Johnson also being obtained by Washington from Homestead — many of the transactions that were announced involving Washington as they were populating their roster. The league set a 16-player limit, and postponed a vote on a Buffalo team entering the league along with the choice of an NNL/NAL commissioner.136 And, most importantly, players on the disbanded (in 1937) 1936 New York Cubans were distributed throughout the league while the rights to players who followed Trujillo’s siren song to Santo Domingo in 1937 reverted to their former teams as their suspensions were lifted.137 The players were supposed to pay fines, but they were never enforced, which led to criticism by fans and sportswriters of the league’s lack of backbone.138

The Senators did not survive the 1938 season, disbanding in August; as Neil Lanctot described it, “[T]he failure of the Black Senators and yet another incomplete playoff series climaxed a nightmarish season for black professional baseball.”139 As in 1937, no official NNL/NAL World Series was held; the Grays won both halves of the 1937 NNL season although the Cubans and Grays both claimed to have won the season’s second-half pennant.140 The rumor mill was busy with speculation that Gus Greenlee would be held accountable for NNL failures and in particular for his poor handling of the Dominican jumpers and would be asked to resign.

The NAL met prior to the 1938 season in Chicago in mid-December 1937. They elected Major R.R. Jackson to a second term as league president, and chose J.B. Martin vice president, Defender sportswriter Frank “Fay” Young secretary, and J.R. Wilkinson of Kansas City treasurer. The NAL admitted the Atlanta Black Crackers and Jacksonville Red Caps as associate members at this meeting.141 When they reconvened on February 19, Atlanta had been raised to a full member, joining the Memphis Red Sox, Chicago American Giants, Indianapolis ABCs, Birmingham Black Barons, and the Kansas City Monarchs in a six-team circuit 142 The NAL decided not to include franchises from Detroit, Cincinnati, or St. Louis as their representatives failed to attend this meeting and put up forfeit money. Rather than including “weak clubs” in an eight-team league, the members felt that “six fast clubs” would be better for the fans.143 As far as postseason play was concerned, a two-game playoff was swept by first-half winner Memphis over second-half champion Atlanta.144

A joint NAL/NNL meeting was held on June 22, 1938, but did not solve the commissioner issue as the Eastern clubs, who met separately prior to the joint meeting, were now against electing one. What the leagues did agree on was “a set of rules by which both leagues could operate and respect territorial rights as well as forcing players to respect contracts.”145 Would the two leagues respect this agreement in their actions or in the breach?

1939

First, though, the two leagues would have to decide upon whether they planned to continue as two leagues or instead merge into one league with two divisions, one in the East and one in the West, much like the original concept of the second NNL in 1933. On Sunday, December 11, 1938, at Chicago’s Appomattox Club, the NAL held its now “regular December meeting” (for the third straight year!) with the principal topic of discussion being the configuration of 1939 Negro League competition.146 Faithful reporter Cum Posey’s Courier column noted that the meeting, called to order by NAL President Jackson at “10:30 sharp (Negro National League owners, please take notice)” included re-electing 1938 NAL officers Jackson as well as Vice president J.B. Martin, Secretary Frank (Fay) Young and Treasurer J.L. Wilkinson, and Posey’s own conveyance of an NNL proposal to merge into one league composed of the best cities, with regular league games between teams from each 1938 league. Posey reported that Jackson would decide by January 10 about forming one combined league.147