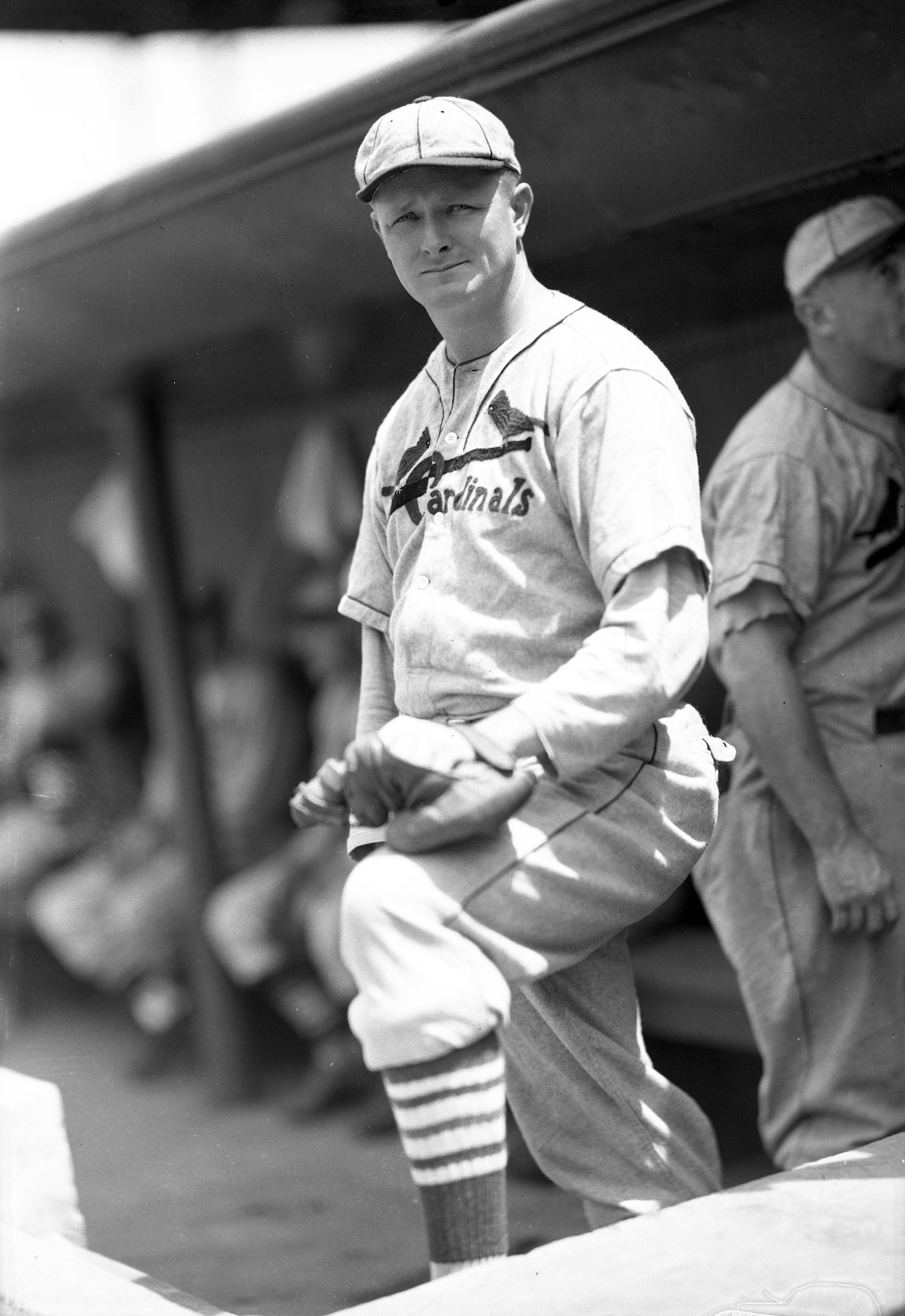

Jim Lindsey

Jim Lindsey made a name for himself pitching for semipro teams in his native Louisiana. Signed first by the Cleveland Indians, he eventually landed with the Cardinals, and pitched for six seasons as a starter and reliever before being released midway through the 1934 season.

Jim Lindsey made a name for himself pitching for semipro teams in his native Louisiana. Signed first by the Cleveland Indians, he eventually landed with the Cardinals, and pitched for six seasons as a starter and reliever before being released midway through the 1934 season.

James Kendrick Lindsey was born in Greensburg, Louisiana, on January 24, 1899.1 One of eight children, he had four sisters and three brothers. His father, Hollis Womack Lindsey, Sr., was a farmer and cattleman and a sheriff, who later became a state game conservation agent for St. Helena Parish. His mother was the former Margaret Minerva Thompson. His sister, Doris Lindsey Holland, was the first woman to serve in the Louisiana legislature.2

Lindsey’s first mound success came at the Chamberlain-Hunt Academy in Port Gibson, Mississippi, where he pitched for two years. He was later with Cleveland, Mississippi, in the semipro Delta League. By 1919 Plantation Jim, as he was then called, was working as a crude-oil stillman and pitching for the the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana refinery, called Stanocola.3

In May 1920 Lindsey and Carlotta Matthews were married. They remained married for 43 years, until Lindsey’s death, and had one daughter and three grandchildren.4

Lindsey signed his first professional contract with the Cleveland Indians in 1920, but although he trained with the team and pitched briefly for the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association, he spent 1920 and 1921 with Stanocola.5 He also pitched in the New Orleans semipro Dixie League for a team known as the Peppermints. In fact, after returning home from most of his minor-league seasons, he would pitch for a semipro team. One such outing took place on September 19, 1926, when his Stanocola team defeated Placquemine 8-0 as Lindsey limited the opposition to two hits and went 3-for-4 at the plate.6

In 1922 Lindsey was among 18 pitchers who reported to Dallas for spring training with Tris Speaker’s Indians.7 On March 27, in an intrasquad game, he virtually assured himself of a roster spot by limiting a squad of Indians regulars to two hits over five innings in a 3-2 win. His control in that game set him apart. In his first two springs with the Indians, he had been the “wildest thing in pitching,” but his efforts that day were universally praised. Smoky Joe Wood, who had won 34 games as a pitcher with the 1912 Boston Red Sox, was finishing his career as an outfielder with the Indians and was also working with Cleveland’s pitchers during spring training. He said, “I never saw Jim look as good as he did today. He could throw the ball where he wanted to. In other years, he has lacked control.”8

The Indians brought Lindsey north. It was his first time out of the South. Upon arriving in Chicago for the first time, Plantation Jim observed, “She’s some village.”9 He was one of 46 players on the Cleveland revolving-door team of 1922. He appeared in 29 games, all but five as a reliever.

Lindsey was pressed into service as a starter for the first time on May 11, pitching the first six innings in a game against the Philadelphia Athletics that Cleveland won, 5-4. His first win came a month later, on June 11 against Philadelphia. He came on in relief and pitched four shutout innings as the Indians, down 8-4 at one point, came back to win, 9-8.

Lindsey’s prowess at the plate was not particularly exceptional. His first major-league hit, a single, came on June 17, 1922, in a 14-inning marathon against Boston. Lindsey put out the fire in the fourth inning and pitched 2? scoreless innings in relief. After singling in the sixth, he injured himself sliding, and came out of the game. His only RBI of the 1922 season came in an 11-3 loss to the Yankees on July 6.

Facing the Yankees on July 9, Lindsey had his best outing of 1922. He came into the game in the bottom of the eighth inning with New York leading. Lindsey allowed an unearned run in the eighth, the Indians tied the score in the ninth, and the game went into extra innings. The Indians scored a pair in the 13th to go out in front and Lindsey held off the likes of Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel, going six innings to earn his third win of the season. Four days later, against the Red Sox, he was almost as good. He came in with runners on first and third and none out in the sixth and allowed but one hit in the last four innings as the Indians came back to win, 4-2. It was Lindsey’s fourth and last win of the season.10

Despite these flashes of brilliance, Lindsey’s overall performance in his rookie season was not superlative. For the season, he went 4-5 and posted an ERA of 5.92. He was sent back to the minors in 1923, and spent most of the next seven seasons in the minor leagues. In 1923 he was with Milwaukee in the American Association and went 8-12. The Indians brought him back for the start of the 1924 season, but he got into only three games, allowing seven runs in three innings, before being sold to Kansas City of the American Association at the end of June. During the balance of the season, he went 3-4 with the Blues before developing neuritis in his pitching arm that lingered into the following season.11

The next five seasons were spent in the Texas League. Lindsey began the 1925 season with Dallas and was released on May 3. He signed on with San Antonio, where an examination determined that he had three bad teeth that were causing his problems. The teeth were removed and his arm came around.12 With the two teams he was 9-10.

Over the next two seasons, Lindsey went a combined 28-24 for San Antonio. The National League champion Pittsburgh Pirates drafted him, but he wound up back in the Texas League, this time with the Houston Buffaloes.13 His two years with Houston, under the tutelage of former minor-league catcher Frank Snyder were exceptional, and he went 46-20. In 1928 he led the circuit with 25 wins as Houston won the league championship, then won the Dixie Series against Birmingham of the Southern Association, taking four straight games after losing the first two. Lindsey pitched Houston to its first win in Game Three.

Lindsey resumed his march back to the major leagues in 1929 by winning six of his first seven starts, including four shutouts. (One of the shutouts was observed by Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey.)14 In all, Lindsey had a league-leading eight shutouts in his 20 wins with Houston that season. At one point, he pitched a league-record 30 straight shutout innings, and he allowed five hits or less in nine games, including a one-hitter. Lindsey was sold to the Cardinals at the end of August.15 In his first start for St. Louis, on September 15, he pitched a complete game as the Cardinals beat the New York Giants 6-4 at Sportsman’s Park. A week later he pitched six innings of one-hit ball against the Brooklyn Robins (the only hit was by pitcher Dazzy Vance), but ran into problems in the seventh and eighth, surrendering six runs as Brooklyn won, 7-2.16

Lindsey had a poor spring training in 1930, and was on the verge of being sent back to the minor leagues.17 But he stayed with St. Louis and had a 7-5 record. On May 13 against the Giants, he entered the game with the bases loaded and none out in the sixth inning and was in command the rest of the way as the Cardinals came from behind to win, 6-4.18 Lindsey was used as both a starter and reliever, and his versatility was apparent in the month of August. On August 6 he preserved a victory over the Cubs, pitching the final two innings in a 4-3 win and striking out Charley Grimm and Gabby Hartnett in the ninth inning.19 In addition to five relief appearances, Lindsey started five games in August. In his starts, he went 3-2. He pitched three complete games in those starts.

On a very deep pitching staff, led by Wild Bill Hallahan and Burleigh Grimes, Lindsey didn’t get noticed much, but he showed his mettle as the Cardinals won the pennant and went on to face the Philadelphia A’s in the World Series. Lindsey got into two games that the Cardinals lost, pitching 4? innings and allowing one run. In Game Two he relieved Flint Rhem, and pitched 2? scoreless innings. In his one at-bat, he singled off George Earnshaw, and in characteristic Lindsey style, he said that he “stretched a triple into a single.”20 Lindsey was effective in the decisive sixth game, pitching two innings, but once again he entered the game too late to make a difference as the Cardinals fell to the Athletics.

Lindsey had one of his best seasons in 1931, primarily as a reliever when relieving was not a role many pitchers aspired to. In his first eight appearances, he pitched 14 innings and allowed but one run. Observed a sportswriter, “No matter how gloomy the outlook, when manager Gabby Street gives him the nod, Big Jim strolls to the hill with the nonchalance of a bride making her fifth trip to the altar. They say, in St. Louis, that his attitude upsets the mental poise of the enemy batters. Regardless of whether there is anything to the theory, he usually gets them out with undue delay.”21

As the Cardinals headed toward a pennant, Lindsey came out of the bullpen for a spot start on September 15, and came through with a 5-0 shutout to bring the Cards to within a game of clinching the pennant.22 It was his sixth win of the season, against four losses. Out of the bullpen, he had seven saves, good for second in the league (the saves are retrospective; the statistic didn’t exist when Lindsey was pitching), and his ERA for the season was 2.77.

The Cardinals once again faced the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. They lost both of the games in which Lindsey appeared in relief, but won the Series in seven games. In two World Series, Lindsey pitched eight innings in relief with no decisions, giving up five runs (three earned) for a 3.38 ERA.

It was common for Lindsey to eat up innings coming out of the bullpen, and this was very much the case on July 20, 1932. He came in when starter Tex Carleton faltered in the second inning, stopped the bleeding, and pitched the remainder of the game, securing his third win of the season, as the Cardinals won, 16-5. For the season Lindsey went 3-3 with a 4.94 ERA as the Cardinals dropped to a sixth-place finish.

Lindsey started 1933 with St. Louis but appeared in only one game before being sent to Columbus at the end of April. Later, when his record was 7-2, he was moved to Rochester, another Cardinals affiliate, in an eight-player transaction. One of the reasons for the deal was that Columbus was over the American Association salary limit. League officials had suspended Lindsey and three other players and fined Lindsey $200. The fine was later rescinded.23 With Rochester Lindsey was only 3-9, but pitched well in the playoffs.

Before the 1934 season the Cincinnati Reds purchased Lindsey’s contract, and he began the season with the Reds.24 On May 23 of that year, after appearing in four games, he was sold to St. Paul of the American Association, and he was back with the Cardinals on June 5. Between June 6 and July 8, he appeared in 11 games, all in relief.

One game in particular was memorable. On July 1 Dizzy Dean was matched up against Tony Freitas of Cincinnati. Although neither pitcher was particularly effective, they were still pitching and the score was 5-5 after nine innings. There was no further scoring, with Dean and Freitas pitching, until the 17th inning. Ducky Medwick put St. Louis in the lead with a homer, but the Reds tied the score in the bottom of the inning. The Cardinals then took the lead in the 18th with a pair of runs off Paul Derringer, who had come in to relieve Freitas in the 17th inning. Lindsey pitched the bottom of the 17th, holding the Reds scoreless. It was Lindsey’s last hurrah with St. Louis. There were two more appearances, neither notable, and he was released on July 10 after going 0-1 with a 6.43 ERA. He may not have been around to see the Cardinals win the pennant over the New York Giants, but that last save, on July 1, made him part of the story.

Lindsey’s next stop was in Atlanta. For four seasons, beginning at age 35, he hurled with success for the Crackers, going 36-25. Used mostly as a reliever, he continued to excel, as he had in his major-league days when given an occasional spot start. His curveball was still effective as he pitched the Crackers to a 9-2 win over Oklahoma City in the second game of the 1935 Dixie Series.25

Released by Atlanta late in the 1937 season, Lindsey signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were short of pitchers.26 In 20 games with the Dodgers, the 38-year-old Lindsey went 0-1 with two saves, with a 3.52 ERA. His last major-league appearance came on September 27, 1937.

In nine major-league seasons, Lindsey won 21 games and lost 20 with a 4.68 ERA. Although the save statistic wasn’t used at the time, he had 19 saves using current the save definition.

In 1938 Lindsey worked out with the New York Giants, who were training in Baton Rouge, so as to be in shape for the Southern Association season, or maybe even another crack at the big leagues. He spent the year in the Southern Association, playing with Chattanooga and Arkansas. There was still something left in the 39-year-old arm. In his last outing of consequence, he pitched a seven-inning shutout as Chattanooga defeated Atlanta 5-0 in the second game of a doubleheader on May 29.27 But the writing was on the wall. For the season Lindsey went 3-8, and his professional baseball career was over.

After he retired from baseball at the end of the 1938 season, Lindsey operated a dairy farm in Baton Rouge. Governor Earl Long appointed him farm manager at the East Louisiana State Hospital in Jackson, and he sold the farm. His daughter Colleen kept Lindsey’s herd, bought another farm, and eventually bred prize-winning Holstein cattle

Lindsey, a member of the Jackson Methodist Church, continued in his position as farm manager until he died on October 25, 1963, at the age of 64.

This biography is included in the book “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals: The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles Faber.

Sources

The following databases and files were used:

Ancsestry.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Paper of Record

GenealogyBank.com

NewspaperArchive.com

Jim Lindsey file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Library

The following newspapers were used:

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Dallas Morning News

New Orleans Item

Rochester Democrat and Chronicle

Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican

State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana)

Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana)

Newspaper articles

Bell, Stuart M., “Jim Lindsey is Big Noise as Cleveland Yannigans Hang it on to the Regulars,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1922, 13.

Dixon, Margaret, “Two Big League Baseball Players Consider Retirement,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), December 4, 1938, 7-B.

Holmes, Tommy, “Robins Lost Golden Opportunity by Failing to Sweep St. Louis Series,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 23, 1929, 22.

Keyerleber, Kyle, “Laughs in Sports,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 17, 1939, 16.

Powers, Francis J., “Red Sox Miscalculate on Joe Sewell’s Ability and Indians win again 4-2,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 14, 1922, 18.

Singleton, W.B., “Familiar Faces in the Big Show,” Dallas Morning News, December 21, 1930, sports section, 2.

Whitman, Burt, “Close Decision Is Given Against Sox, Who Lose,” Boston Herald, July 14, 1922, 15.

Notes

1 There is some question about his actual birth date and year, with sources listing years from 1896 through 1900. Baseball-Reference.com shows January 24, 1896. According to his draft card, the date is January 24, 1899. The Louisiana Marriage Records Index reflects that Lindsey was born “about 1899.” The 1900, 1910, and 1940 census records also reflect the 1899 birth year, but the 1920 and 1930 census records showed him being born in 1897, and his death certificate lists his date of birth as January 24, 1898. Papers in his file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library give dates in 1900. One date, from a release titled “Major League Newcomers,” shows February 23, 1900.

2 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, March 24, 1936.

3 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, March 5, 1920, 2

4 New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 5, 1920.

5 New Orleans Item, October 26, 1922, 18.

6 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, September 20, 1926.

7 Dallas Morning News, March 6, 1922, 10.

8 Stuart M. Bell, “Jim Lindsey is Big Noise as Cleveland Yannigans Hang it on to the Regulars,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1922, 13.

9 Bell, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 8 1922, 16.

10 Francis J. Powers, “Red Sox Miscalculate on Joe Sewell’s Ability and Indians win again 4-2,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 14, 1922, 18; Burt Whitman, “Close Decision Is Given Against Sox, Who Lose,” Boston Herald, July 14, 1922, 15.

11 W.B. Singleton, “Familiar Faces in the Big Show,” Dallas Morning News, December 21, 1930, sports section, 2.

12 Springfield Republican, December 21, 1930, 18.

13 Baton Rouge Advocate, October 13, 1927, 10.

14 Boston Herald, May 26, 1929, 21.

15 Dallas Morning News, September 1, 1929, sports section, 2

16 Tommy Holmes, “Robins Lost Golden Opportunity by Failing to Sweep St. Louis Series,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 23, 1929, 22.

17 Sarasota Herald Tribune, March 27, 1930, 10.

18 New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 14, 1930, 15.

19 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 7, 1930, 16.

20 Lindsey Obituary on file in the Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

21 Sarasota Herald Tribune, June 1, 1931, 6

22 Baltimore Sun, September 6, 1931, 15.

23 Milwaukee Journal, November 17, 1933, D-7.

24 Montreal Gazette, February 20, 1934, 12.

25 Kenneth Gregory (Associated Press), “Jim Lindsey Hurls great 9-2 victory, in the Baton Rouge Advocate, October 1, 1935, 8.

26 Miami News, August 4, 1937, 7.

27 Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, May 30, 1938, 6.

Full Name

James Kendrick Lindsey

Born

January 24, 1899 at Greensburg, LA (USA)

Died

October 25, 1963 at Jackson, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.