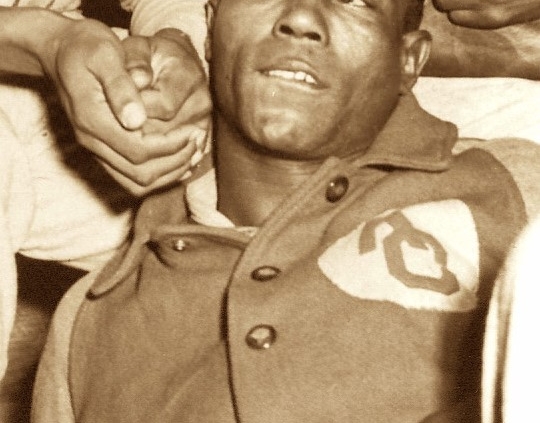

Frank Bradley

Frank E. Bradley, a fireballing right-handed pitcher who played in six seasons for the Kansas City Monarchs before suffering a career-ending wound in World War II, was born on February 3, 1918, in Benton, Bossier Parish, Louisiana. He was the son of June and Adline (Gates) Bradley. If Frank had any siblings, no mention of them has survived in census records.1 Frank appears to have been the first generation of his family to be able to write; his father’s World War II draft record, dated 1942, is signed by June Bradley with his mark, and Frank’s record contains his signature.2 According to their draft records, both father and son worked at the Rough and Ready plantation in Bossier Parish, which was owned then (and still was in 2021) by the Stinson family.3

Frank E. Bradley, a fireballing right-handed pitcher who played in six seasons for the Kansas City Monarchs before suffering a career-ending wound in World War II, was born on February 3, 1918, in Benton, Bossier Parish, Louisiana. He was the son of June and Adline (Gates) Bradley. If Frank had any siblings, no mention of them has survived in census records.1 Frank appears to have been the first generation of his family to be able to write; his father’s World War II draft record, dated 1942, is signed by June Bradley with his mark, and Frank’s record contains his signature.2 According to their draft records, both father and son worked at the Rough and Ready plantation in Bossier Parish, which was owned then (and still was in 2021) by the Stinson family.3

Although a profile of Bradley published late in his life says Bradley’s baseball career began in 1935,4 the first newspaper mention of him is in 1936 with the Benton Eagles. “Most of us went to school together when we were kids,” he told a reporter years later. “We just got together after work. We played in the park. Sometimes we played in oil fields.”5

By the next year, Bradley had joined the Shreveport Giants. He was an immediate standout with the team, striking out 14 in a 9-1 win over the Clintonville Merchants in the summer of 1937.6 Only two days later, he was described as the “speed ball king par excellence” and the “no. 1 man in the invaders’ hurling corps” before a game with the Studebaker Athletics.7

But Bradley was not long for Louisiana baseball. He told the story of his discovery by scout Winfield Welch: “I was chopping cotton. The man said he was looking for Dick Bradley to play baseball. I dropped that hoe 50 feet and started running.”8 Welch was a scout for the Kansas City Monarchs. Bradley was going to the big time.

Bradley made his Monarchs debut that summer against South Bend. He was nervous early in the game and was having trouble getting his fastball over the plate.9 Satchel Paige walked out to the mound and explained to Bradley that if he would just settle down and throw his fastball over the plate, nobody was going to get near it. “I struck out the next nine batters,” Bradley recalled.10 Bradley ultimately finished up with 17 strikeouts in the game.11 A few days later, Bradley and Floyd Kranson threw a combined five-hitter against Indianapolis.12 Bradley’s next start did not go as well, as the Beatrice Blues beat Kansas City 13-10. Bradley started the game but was yanked during Beatrice’s six-run second and took the loss.13

A few days later, Bradley started the second game of a doubleheader at Kansas City’s Muehlebach Field against the Cincinnati Tigers. The Monarchs won the game, 7-1, “behind the brilliant mound work of Rookie Bradley, 20 years old [sic]. It was the youngster’s first appearance at Muehlebach Field, and he celebrated by holding the Tigers to five hits. More than 3,200 fans attended the games.”14

By the beginning of the 1938 season, the newspapers were touting Bradley as one of the major stars of the Monarchs pitching staff. Before an April 1938 game against the Hutchinson Larks, the Hutchinson News wrote that “Frank Bradley, a big right-hander who is expected to be another Satchel Paige, has already uncovered one of the fastest balls of any pitcher to ever wear a Monarch uniform.”15 The Springfield papers joined in the hype the following day: “The Kansas City Monarchs, who play our Cardinals here Saturday, have a pitcher they claim is faster than Bob Feller. He’s 18-year-old Frank Bradley. The Monarchs have battled Feller four times in exhibition games, so they should know how fast he is.”16

Bradley pitched a gem five weeks later against the Chicago American Giants, holding the Giants to only two hits. Only two months into his first full season, “Kid Bradley” was already drawing comparisons to two future Hall of Famers: “[T]he youngster is rated as the best rookie hurler the Monarchs have ever had. He has a great fast ball and is rated as speedy as ‘Satchel’ Paige or ‘Bullet’ Rogan, speed ball pitchers deluxe.”17

Bradley continued to pile up the strikeouts as the Monarchs’ year continued. The Monarchs had a laugher at the end of June, whipping the Studebaker Athletics, 15-1. Bradley threw three innings, struck out six, and surrendered two hits and one run.18 A week later, Bradley showed off his stamina, pitching the final three innings of the first game of a doubleheader against the Memphis Red Sox and then starting the second.19

Bradley was clearly a gate draw in the Negro League fan community by midsummer of that year. The press raved: “Bradley, a fireball pitcher who has become the newest sensation of Negro baseball with his amazing victory record, is only 19 years old. … [H]e is expected to start tomorrow night’s game for the Monarchs.”20 Perhaps the highlight of Bradley’s summer was when he pitched a six-inning no-hitter against the Birmingham Black Barons on July 14 in Oklahoma City; the game was called after 5½ innings because of rain, but Bradley had pitched the Monarchs to a 3-0 victory.21

Shortly thereafter, the Monarchs were in Saskatchewan and, in a promotional article headlined “The Monarchs Are Coming!” a local paper called Bradley “the ‘Bob Feller of the Negro league.’”22 Bradley relieved Floyd Kranson in the sixth inning of the next day’s game, ultimately losing on a two-run rally in the bottom of the ninth that was capped off by a double by the opposing pitcher.23

Two weeks later, the Monarchs were in Davenport, Iowa, playing the Illinois-Iowa League All-Stars. Thanks to a four-run first, the Monarchs defeated the All-Stars, 6-1. According to the local paper, Kansas City pitchers Big Train Jackson, Johnny Marcum, and Bradley “displayed plenty of class, keeping the All-Stars under control the entire contest.”24

The Monarchs staged a festive doubleheader against the Memphis Red Sox to open their 1939 season. Pregame ceremonies included a flag-raising and a stadium parade with the Elks band and drill team, the Negro American Legion drum and bugle corps, the Junior Negro Scouts drum and bugle corps and the Kansas City Negro jazz and swing orchestra. The Monarchs came into the season hot, having won 10 of 15 preseason games.25 According to the Kansas City Star, “Manager Andy] Cooper will pitch ‘Kid’ Bradley, 20-year-old speedball star, and Hilton Smith, who led the Monarch staff, with twenty-six victories and six losses, against the Memphis invaders.”26 Cooper expected Bradley to “have a big year,” wrote a reporter.27

Bradley seemed to heat up as summer began. He beat Decatur, 7-2, on the last day of June, striking out six in six innings and adding a double from the plate. While other reporters emphasized Bradley’s fastball, the Decatur paper praised his “fast breaking curve ball” as well.28

A few days later Bradley came in from the bullpen, relieving Monel “Lefty” Moses after he gave up four hits to the Chicago American Giants in the first inning. Bradley shut Chicago down, scattering five hits in the last eight innings.29 One week later, Bradley was back on the mound for an important league game against the Chicago American Giants in which he tossed a five-hitter to beat the Giants, 14-1.30

Bradley made several relief appearances in the second half of July 1939. He got what would today be called a save in a game against Winnipeg, entering the game during a ninth-inning rally and ending the threat.31 At the end of the month, he starred from both the mound and the plate in a league game against the American Giants. Bradley relieved Willie Jackson in the second and pitched into the sixth, when an 11-run outburst from the Monarchs decided the game. Bradley allowed only one run in his stint and hit a double while notching the win.32

Bradley had a hard-luck start in late August against the Muncie Citizens. Despite giving up only six hits in 8⅓ innings (with eight strikeouts), he did not get his accustomed run support and wound up losing 3-2.33

A week later, Bradley got a chance to take on the legendary barnstorming team, the House of David. Satchel Paige started, working the first three innings, and Bradley went the rest of the way as the Monarchs triumphed, 10-5.34

In late September after the Monarchs had wrapped up another championship, Bradley got a chance to wear a different uniform, joining the barnstorming Satchel Paige’s All-Stars – an indication of just how high Paige’s respect for the young pitcher was. The All-Stars played a doubleheader against the Monarchs, but Paige’s start in game one was a disaster. The Monarchs beat the All-Stars 11-0, with most of the runs coming off their moonlighting teammate’s pitching. The second game was a different story, but ultimately the same result, as the Monarchs completed the doubleheader sweep, 1-0. Johnny Marcum started for the All-Stars, giving up the only run in the fifth on Ted Strong’s home run, and Bradley shut out his Monarchs teammates the rest of the way.35

As the 1940 season opened, Bradley was still a frequent starter for the Monarchs who also came out of the bullpen. He lost an early April game as the starter against the Tyler Black Trojans,36 but only a week later, he was the Monarchs’ third pitcher of a game with the Toledo Crawfords that had gotten away early on the Crawfords’ five-run first. Bradley managed to tame the Crawfords’ bats, coming in for the late innings, but it was far too late to salvage a win.37

On a chilly night in early June, “Frank (Fireball) Bradley” was the starter for the Monarchs in an important Negro American League game against the Chicago American Giants. According to the press account of the game, Bradley had everything working that day: “Fogging the third strike past the waving bats of 10 rivals, the Kansas City star blanked his foes in six innings, while his mates mauled Wadel Miller, losing pitcher, for 12 hits, two of them for homers and a pair of doubles.”38 In fact, one of those home runs was by Bradley himself; for the game, he was 2-for-4 from the plate.39

Later that month, Bradley was coming out of the bullpen again, replacing Allen Bryant on the mound in a game against the Belmar Braves. Bradley managed to hold the line, striking out six and scattering five hits over the last five innings of the game. The Monarchs game became exciting at the end as “Kansas City staged a two-run rally in the ninth, and Bradley himself started it with one out. After fouling off five straight pitches and flopping all over the plate on every swing, he caught hold of one of Sahlin’s good pitches and belted it over the right field fence for a double.”40 Although the Monarchs lost the game, 5-4, “Bradley … stole the show. He went thru more antics than were necessary, both at the plate and on the mound, but the crowd loved it.”41

A couple of weeks later, against the Stillwater Boomers, Bradley took a no-hitter into the bottom of the eighth, ultimately striking out 13 in eight innings of work. The Boomers closed the margin in the bottom of the ninth, scoring four off the Monarchs’ bullpen, but the Monarchs won the game, 12-6.42

Bradley was nearly as good later that month against an all-star team from the Worthington Cardinal and Sioux Falls Canaries of the Western League. On this occasion, “So effective was Bradley’s ‘swift’ that through the first eight stanzas the All-Stars could boast of but two hits – both of which were over second base but did not reach the outfield. … During this time Bradley had whiffed ten of the leaguers. … In one stretch during the fourth, fifth and sixth cantos seven of the honor team were strikeout victims in succession. Bradley ended the game with 12 strikeouts.”43 A few days later, Bradley and Hilton Smith combined on a three-hitter as the Monarchs whipped Richland Center, 10-0.44

In late August, Bradley pitched twice against the Ethiopian Clowns within a few days. In the first game, a 4-3 Kansas City victory, Bradley and Hilton Smith handled the pitching duties and “showed speed and jug-handle curveballs in abundance.”45 Bradley struck out the side in the first and second and ended with 10 strikeouts in five innings of work.46 “Speed Bradley” threw a gem against the Clowns in the second game but wound up being let down by his bullpen. Bradley gave up only a single scratch hit across the first seven innings and struck out 18 in his nine-inning stint. The Monarchs eventually lost the game in the 11th.47

Bradley’s final recorded start for 1940 was in mid-September against the Local 210 Oilers. He entered the game in the second and pitched the final seven innings, limiting the Oilers to five hits and striking out 12.48

By the beginning of the 1941 season, Frank Bradley was routinely being called one of the veterans of the Monarchs’ pitching staff.49 He dominated in a 9-1 triumph over the La Crosse Blackhawks in June, striking out nine while going 3-for-5 from the plate.50 A week later, he lost a heartbreaker against the New York Black Yankees, a league opponent, for which he had only himself to blame. Bradley had pitched well, holding New York to only two hits and striking out six while going 2-for-4 from the plate, but he ended up losing, 3-2, when he balked in the winning run for New York in the top of the eighth.51

In mid-July Bradley was the Monarchs’ third pitcher in a three-way 3-0 shutout of the Belmar Braves, giving up three hits in the final three innings and striking out two.52 The shutout lengthened Belmar’s scoreless drought against the Monarchs to 29 consecutive innings.53 Bradley threw a complete game in his next start but lost to the Brooklyn Bushwicks, 3-1, though he struck out seven, walked only two, and managed a 1-for-3 day from the plate.54 Bradley pitched well again in an early August start against the Studebaker Athletics, but it must be conceded that the Athletics gave him a lot of help. The Monarchs won the game, 11-0, but the 11 errors the Athletics rang up probably had something to do with that. Five of those 11 errors were recorded by a single player, Athletics shortstop Stanley Wrobel, who also got the only extra-base hit among the Athletics’ five hits for the day.55

As the 1941 season wound down, the Monarchs lost to the Birmingham Black Barons, 5-0. Bradley wasn’t sharp, giving up nine hits and four runs in his seven innings of work, with only four strikeouts.56 His final two appearances for the season were both in exhibition games. In early October the Monarchs took on Bob Feller’s All-Stars, one of the series of games Negro League teams played against barnstorming White major leaguers over the years. Bradley did not pitch, but he did pinch-hit for fellow pitcher Hilton Smith in a 4-1 loss.57 The next day the Monarchs defeated Frigidaire, 5-2. Satchel Paige started and hurled the first three frames. Bradley took the mound in the fourth and pitched five strong innings, striking out nine, walking only one, and scattering four hits. He was 2-for-2 at the plate.58

Bradley was eager to get started as the 1942 season approached, arriving early at the Monarchs’ spring-training camp in Monroe, Louisiana.59 The Monarchs started Bradley in the opening game of an early-season doubleheader against the Birmingham Black Barons, which the team lost by a 2-1 score. The Monarchs took the second game, 8-6, thanks to Barney “Bonnie” Serrell’s circus catch of what would have been a three-run homer for the future Harlem Globetrotter Reece “Goose” Tatum.60

Although reports of Bradley starts are scarce for 1942, he was routinely referred to as part of the Monarchs’ sterling pitching staff.61 The Harrisburg Evening News was effusive in August: “Two other hurlers on the Monarchs who have exceptionally fine records and who have the throwing arms to back up arguments in their favor are Hilton Smith and Frank Bradley.”62 Although he was not used during the World Series, the newspapers took notice of Bradley as an important part of the Monarchs’ pitching staff before Game One against the Homestead Grays.63

In 1943 several newspapers continued to list Bradley as a member of the Monarchs’ pitching staff.64 However, by this time he was in the Army and played for the 915th Squadron at Dover Air Force Base. One game account noted, “PFC Frank Bradley, formerly with the Kansas City Monarchs, drove in four runs. His homer in the third with a mate aboard accounted for two and his fifth-inning single drove in two more.”65 Bradley remained in the Army for the remainder of World War II, with the duration of his service spanning October 5, 1942 to December 8, 1945.

Tragically, due to a wound in the bend of his arm, Bradley’s career ended with his Army service. He returned to his hometown of Benton and bagged groceries for a living. On the positive side, with his baseball barnstorming days and military service both at an end, he married his longtime love, Maurine Moore, on June 22, 1946.66

Decades later, Bradley’s friends remembered his talent and what might have been. His childhood friend Riley Stewart, who knew both Bradley and Satchel Paige well, said, “Satchel said the hardest thrower, without a doubt, was Dick Bradley. Dick was a strong power pitcher with a curveball. Dick was in that class with (Nolan) Ryan.”67 “[Satchel] said [Bradley] could throw that ball and make it look like an aspirin tablet,” Stewart remarked, and then added, “Dick Bradley could throw the ball as hard as any human being could in those days.”68

Bradley attended a Monarchs reunion in 1995. “It’s a really good feeling,” he said. “I’m glad to go. Imagine I’ll see some old friends I haven’t seen in more than 50 years because I saw a lot of old teammates in Cooperstown. I’m really looking forward to seeing that old ballpark again.”69

Several of the best stories about Bradley’s career appeared after his playing time was over. Among these were the facts that “[h]e pitched a no-hitter against the Memphis Red Sox and came out on the short end of a 1-0 pitching duel with Bossier City’s Riley Stewart before a four-year stint in the army beginning in 1943.”70 Like Satchel Paige, “When he had his good stuff, Bradley would call in the outfielders and infielders and strike out the side.”71

Bradley recalled late in his life that he would frequently finish up for Paige – Satchel for the first six innings and Bradley finishing up the game. “I’d say the toughest hitter I ever faced was Josh Gibson,” he said. “I think I probably faced him about 20 times.”72 Bradley admitted to having added one homer to Gibson’s prodigious career total.73

Fifty years after he retired from the game, Bradley still remembered those days: “He [said] traveling and playing the game [were] his best memories. ‘I miss the game, I miss the friendships. … I dream about baseball all the time.’”74

In his later years, Bradley became known for his career with the Monarchs throughout his home parish in Louisiana. On August 11, 2001, the Shreveport Swamp Dragons honored the 83-year-old hurler, and he threw out the ceremonial first pitch before the team’s game against the Wichita Wranglers.75

After his death on December 2, 2002, in Benton, hometown newspaper columnist Bradley Hudson wrote an elegiac tribute to the deceased Negro League star. The writer remembered Bradley walking past his house every morning and evening going back and forth to work at the local creosote plant, “carrying his lunch in a greasy brown paper bag. He was friendly, polite and a very nice man who took time occasionally to tell us to do our best in school. He would even take our baseballs and show us how to throw a curveball or a fastball. … Little did we know that this same man once had a fastball that even Satchel Paige envied.” The columnist wrote, “Bradley never seemed bitter about his fate. I never once detected a trace of anger in him. He realized that it was just the times in which he grew up. … Major League baseball has attempted to make amends by honoring Negro League stars. They earned it. … I’ll always treasure having known him.”76

Frank Bradley is buried in the Benton Community Cemetery, on Highway 162 just east of the hometown where he lived most of his life.

Sources

Ancestry.com was consulted for public records, including census information, marriage and death records, and Frank and June Bradley’s World War II draft registration cards.

Notes

1 Census records for the family for the years 1920, 1930, and 1940 have been reviewed via Ancestry.com, with no additional children listed.

2 See World War II draft registration cards for June Bradley and Frank Bradley, Ancestry.com.

3 For a brief history of the Rough and Ready Plantation, see the Bossier Parish Libraries History Center, http://bossier.pastperfectonline.com/photo/67D885DF-1394-4E78-9C89-473991522949.

4 “Negro Leagues Saw Great Baseball,” The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), July 24, 1991: 83.

5 Victoria L. Coman, “‘I Miss the Game; I miss the friendships,’” The Times, November 20, 1996: 41.

6 “Colored Team Wins Against Merchants,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, August 20, 1937: 14.

7 “Colored Nines Are Booked by Manager,” South Bend Tribune, August 22, 1937: 11.

8 “Negro Leagues Saw Great Baseball.”

9 Late in Bradley’s life, a newspaper retrospective of his baseball career reported that his fastball was “99 miles-per-hour.” Jerry Byrd, “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall [sic] in Benton Parade,” Bossier (Louisiana) Press Tribune, December 11, 1997: 16. It is unclear whether Bradley himself made this claim, or one of his former teammates did. Since Bradley’s career was before the era of even the most primitive speed guns, we will never know how seriously to take the claim.

10 “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall.”

11 Clint Land, “Baseball Pitching Legend Honored,” Bossier Press Tribune, August 13, 2001: 7.

12 “Monarchs Have Easy Victory,” Manhattan (Kansas) Mercury, August 28, 1937: 6.

13 “Pociask Lets Barnstormers Down Rudely,” Beatrice (Nebraska) Daily Sun, September 2, 1937: 6.

14 “The Monarchs Take Two,” Kansas City Times, September 7, 1937: 13.

15 “New Players with Monarchs,” Hutchinson (Kansas) News, April 28, 1938: 2.

16 John Snow, “Press Box Gossip,” Springfield (Missouri) Leader and Press, April 29, 1938: 2.

17 Hank Casserly, “Invaders Have Great Record in Past Week,” Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), June 1, 1938: 13.

18 Bob Overaker, “Monarchs Rout Studebakers,” South Bend Tribune, June 28, 1938: 10.

19 “Hold Monarchs Even,” Kansas City Times, July 4, 1938: 6.

20 “Negro Bob Feller,” Minneapolis Star, July 11, 1938: 11.

21 Christopher Hauser, The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 104.

22 “The Monarchs Are Coming!” Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan), July 21, 1938: 13.

23 “Pitcher Wins for Giants,” Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan), July 23, 1938, 12.

24 “Colored Nine Gets 4 Runs in First Frame,” Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), August 2, 1938: 12.

25 “Monarchs Play Today,” Kansas City Star, May 14, 1939: 9.

26 “Monarchs Play Today.”

27 “Al Krueger Will Oppose K.C. Ball Club,” Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), May 23, 1939: 21.

28 Howard V. Millard, “Bloomers Open Here Tonight; Ladies Guests,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, July 1, 1939: 5.

29 Hank Casserly, “Former Red Hurler Will Aid Locals,” Capital Times, July 5, 1939: 13.

30 “K.C. Monarchs Defeat Giants,” Minneapolis Star, July 12, 1939: 18.

31 “Monarchs Capture Twin Bill,” Winnipeg Tribune, July 18, 1939: 13.

32 “Kansas City’s Negro Team Beats Chicago,” Des Moines Register, July 29, 1939: 9.

33 Evan Owens, “Citizens Play at Lafayette,” Muncie (Indiana) Evening Press, August 25, 1939: 16.

34 “Colts Defeat Davids at Storm Lake, 10-5,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, September 6, 1939: 12.

35 “No Run for All-Stars,” Kansas City Times, October 2, 1939: 11; “Paige to Face Monarchs,” Kansas City Star, October 1, 1939: 20.

36 “Black Trojans Outhit K.C. Nine but Lose, 2 to 7,” Tyler (Texas) Morning Telegraph, April 8, 1940: 2.

37 “Toledo Negro Team Wins; Owens Sprints,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 17, 1940: 19.

38 Brad Wilson, “Monarchs Beat Giants, 7 to 3,” Des Moines Register, June 11, 1940: 14.

39 Wilson.

40 “Belmar Nine Conquers Kansas City Monarchs,” Asbury Park Press, June 22, 1940: 8.

41 “Belmar Nine Conquers Kansas City Monarchs.”

42 “Kansas City Monarchs Trounce Boomers, 12-6,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), July 9, 1940: 11.

43 “Monarchs Win Here 7-4; Cards Beat Canaries 5-4,” Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, South Dakota), July 22, 1940: 8.

44 “Monarchs Whitewash Richland Center, 10-0,” Wisconsin State Journal, July 26, 1940: 10; “K.C. Monarchs Wallop Richland Center, 10-0,” Capital Times, July 26, 1940: 16.

45 “Negro Nines Shine,” Winnipeg Tribune, August 23, 1940: 12.

46 “Negro Nines Shine.”

47“Winners Pair Single, Double in 11th Frame,” Daily Times, August 28, 1940: 11.

48 “Paige Works 2 Heats; Gets 6 on Strikes,” The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), September 18, 1940: 22.

49 “Negro Baseball Champs to Play,” Monroe (Louisiana) Morning World, May 4, 1941: 11; “Kansas City Outfit Meets Black Barons Sunday in Twin Bill,” Birmingham News, May 9, 1941: 17.

50 Earl H. Voss, “Third Place Club Only Single Game Behind La Crosse,” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, June 24, 1941: 8.

51 “Monarchs Lose on a Balk,” Kansas City Times, July 1, 1941: 12.

52 “Monarchs Trip Braves, 3 to 0,” Daily Record (Morris County, New Jersey), July 19, 1941: 4.

53 “Brave String of Scoreless Innings Is 29,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, July 19, 1941: 9.

54 “Bushwick Club Downs Monarchs,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 24, 1941: 15; “Bushwicks Win, 3-1,” New York Daily News, July 24, 1941: 540.

55 “Monarchs Win 11-0,” South Bend Tribune, August 7, 1941: 11-12.

56 “Black Barons Win by 5 to 0 Score from Monarchs,” Oshkosh Northwestern, September 12, 1941: 17.

57 “Feller and Paige Good, but Others Look Better,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 6, 1941: 13.

58 “Monarchs in 5-2 Win Over Frigidaire,” Journal Herald (Dayton, Ohio), October 7, 1941: 9.

59 “K.C. Monarchs Head South for Spring Training Siege,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 28, 1942: 16.

60 R.S. Simmons, “Speaking in General,” Weekly Review (Birmingham, Alabama), April 24, 1942: 7.

61 “Black Barons Play Jacksonville in Opener, Sunday,” Weekly Review, May 8, 1942: 7; “League Twin Bill Here,” Kansas City Times, May 30, 1942: 7; “E.C. Giants Tangle with Kansas City,” The Times, June 26, 1942: 47; “Monarchs Play Here Thursday,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, July 15, 1942: 5; “‘Satchel’ Paige and Kansas City Monarchs in Yankee Stadium’s Biggest Attraction Sunday, Aug. 2,” New York Age, August 1, 1942: 11.

62 “Stars of Negro Loop Play Here,” Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), August 11, 1942: 6.

63 “Satchel Paige Faces Grays Here Tonight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1942: 26.

64 “Monarchs Here Sunday,” Kansas City Star, May 9, 1943: 24; “Kansas City Monarchs Believe They’ll Win Fifth Championship,” New York Age, July 24, 1943: 11.

65 “915th Squadron Blanks Fort Miles Hilltoppers,” News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), July 15, 1943: 25.

66 Her name was sometimes spelled alternately as “Maurine” or “Maureen” in various sources.

67 “Negro Leagues Saw Great Baseball,” The Times, July 24, 1991: 83.

68 “’I Miss the Game; I Miss the Friendships,’” The Times, November 20, 1996: 41.

69 “Ex-Players Set for Historical Fete,” The Times, October 24, 1995: 17.

70 “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall in Benton Parade,” Bossier Press Tribune, December 11, 1997: 16.

71 “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall in Benton Parade.”

72 “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall in Benton Parade.”

73 “Former Pitcher Is Grand Marshall in Benton Parade.”

74 “’I Miss the Game; I Miss the Friendships,’” The Times, November 20, 1996: 41.

75 Charlie Cavell, “Swamp Dragons Blow Three-Run Lead in Loss,” The Times, August 11, 2001: 17.

76 Bradley Hudson, “Bradley a Silent Hero,” The Times, December 15, 2002: 100.

Full Name

Frank E. Bradley

Born

February 3, 1918 at Benton, LA (USA)

Died

December 2, 2002 at Benton, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.