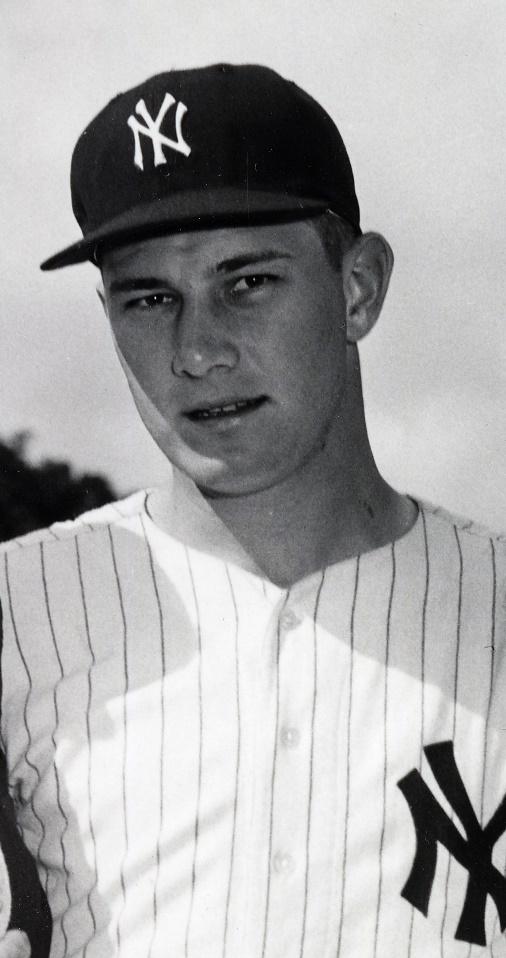

Frank Leja

The day the Yankees won Game Two of the 1953 World Series, 17-year-old Frank Leja was in New York signing a contract that made the sports pages across the country. The second-youngest Yankee ever reportedly received a $100,000 bonus.1

But like many mid-1950s “bonus babies,” Leja was a victim of the revised “bonus rule” of 1952, which required free agents signed for more than $4,000 to remain on a major league roster for two years.2 Successes like Al Kaline and Sandy Koufax were rare — and Koufax took several years to break through. These stars overshadowed the teenagers and college players who could not meet unrealistic expectations, were improperly developed, or worse.

Yankees manager Casey Stengel would look down the dugout bench and call, “Leej!” Leja would stand up and ask what Stengel wanted and the skipper would say, “Nothing. Just sit right there.”3

And that’s what Leja did for two seasons until he met his roster requirement. The first baseman got into just 19 games as a Yankee and made merely seven plate appearances, while playing in the field for 12 innings. He was sent to the minors in 1956 and it took six years and over 1,000 games to return to the top level with the Los Angeles Angels. Seven games later, his major-league career was over.

Leja was one of the three best players who never made it big in the major leagues, seven-decade Red Sox player/manager/coach Johnny Pesky told Leja’s son, Frank Carl.4

Frank John Leja (the family name is Polish) was born on February 7, 1936, and grew up in Holyoke, then a thriving mill city on the Connecticut River in west-central Massachusetts. Leja and his younger sister Louise lived with their father and mother, Frank Sr. and Julia (Wojtasczyk). His father was an auto parts salesman, and his mother was at home. The Lejas were renters in neighborhoods of single- and multi-family homes in Holyoke.

Leja started playing organized baseball at age seven.5 Louise said that while they were growing up, her brother asked her to throw him grounders in their packed dirt backyard.6 In junior high school in the late 1940s, Leja was coached by Holyoke native Ed Moriarty, a former Boston Brave. Moriarty encouraged Leja to give up switch-hitting and hit left-handed.7

Holyoke High School was in the middle of a ten-year period (1944 to 1953) when it advanced to the state baseball finals five times.8 In 1953, Leja’s senior year, Moriarty coached the high school team. That squad included pitcher Roger Marquis, who played one game as an outfielder with the Baltimore Orioles in 1955. Holyoke won the state championship for the second time in four years.9 Leja, who had grown to 6-feet-4 and 205 pounds, led the team at the plate in his senior year.

With only 200 boys at 1,000-student Holyoke High, Leja played and excelled in football, basketball, and baseball. A football injury in his junior year encouraged him to concentrate on baseball, especially with the prospect of an immediate pro baseball signing bonus.10

He struggled at the plate as a sophomore and junior, hitting below .225 both years, with a total of nine extra base hits and ten RBIs. His breakout year as a senior, 1953, brought the major league scouting spotlight to Holyoke. With hits in all 21 games, he batted .432, with five home runs, five triples and a double. He had 22 RBIs and 19 stolen bases. His solo home run in a 1-0 sectional playoff win propelled Holyoke to the state championship.

Holyoke High principal Harry Fitzpatrick said Leja “was a good student, always a gentleman, quiet, unassuming. He was liked by students and teachers. He was intelligent and mature for his age…He’s a star athlete but beyond that, a true sportsman.” 11

“The first one at practice, the last to leave the field,” said Moriarty. “He’d stay there until he perfected his fielding.”12 That made the left-handed throwing Leja more than a one-dimensional slugger. He was inspired by Stan Musial, also of Polish descent, who played the position frequently.13

Leja graduated on June 15 and deferred matriculation to Dartmouth College, where the baseball team was coached by former Yankee All-Star and Detroit Tigers manager Red Rolfe. Rolfe advised Leja to showcase his talent, because a bonus might disappear if his baseball career foundered in college.14

The next day, on June 16, Leja was in the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants. During the next two weeks he visited Milwaukee, Chicago, and Boston, working out for the Braves, White Sox, and Indians (who played the Red Sox in Boston from June 23-25).15

The Boston tryout was reported in the Boston Traveler and included a picture with Indians Manager Al Lopez, who was quoted in the caption that Leja would be Luke Easter’s successor at first base. When the Indians traveled from Boston to New York in late June, Leja was directed to report to Commissioner Ford Frick’s office.16

“I got grilled,” Leja said. “But there I was, 17 years old and what did I know about baseball laws. I just wanted to play ball. I was scared in that real big office, with Frick asking and somebody writing all that stuff down. It was like I was a criminal.” 17 When Frick inquired whether Leja had been given gratuities, Leja asked what those were. Frick snapped, “Gifts, money, spikes, gloves, things like that?”18

Leja explained the Indians gave him meal money and a glove “because I only had a high school glove. I wasn’t from a wealthy family.” And Leja reported they said, “That’s it!” 19

The Commissioner fined the Indians, Braves, and Giants for tampering. It was a national story; Leja was declared ineligible and could not be signed until September 10. He was suspended from playing American Legion baseball but was reinstated after submitting an affidavit stating he had not been negotiating with the teams.20

In September, tryouts resumed. On the 29th, the day before the World Series began, Frank and his father began final negotiations with the White Sox, Indians, and Yankees in New York.

The White Sox didn’t want Leja to sit on the bench; he refused a minor-league deal. The Indians rejected Leja’s proposal for an $85,000 bonus. Then the Lejas met with Yankees general manager George Weiss and the club’s legendary scout, Paul Krichell, who found Leja and described him as “another Lou Gehrig.”21

Leja’s $25,000 bonus was far less than speculated ($100,000) and he agreed to keep the amount confidential. “This is an opportunity that’s here now,” Leja reflected. “I can get my education later.”22

“I was always waiting for the Yankees,” said Leja. “There’s something different about them. You put their uniform on and you want to work your fingers to the bone.”23

Manager Stengel said, “He’s the most experienced 17-year-old I ever saw. After all, he’s been around both leagues [trying out]. I like the boy.” 24

In October the Yankees sent Leja to Puerto Rico to play winter ball for Harry Craft (manager of New York’s Triple-A team in Kansas City) and the San Juan Senadores. Leja later recalled, “After two months I started getting sick of the same routine: five cuts, shag, then sit on the bench and cheer while other guys played. I played three games in about three and a half months and learned nothing.”25

At spring training in 1954, the pattern repeated. “I’m going to play you,” he remembered Stengel saying. “[Johnny] Mize [the backup at first base] is gone and we need a first baseman.”26

But Leja had already slipped on the depth chart. Originally touted as backup to Joe Collins at first, Leja was displaced by veteran Eddie Robinson, acquired in December. Then another first baseman, Moose Skowron, made the team out of spring training.

When Leja got his first paycheck in April, it was based on 1953’s major-league minimum salary of $5,000, not the $6,000 minimum in effect for 1954. Leja raised this discrepancy with AL player representative Allie Reynolds, who bumped it to the front office. The issue then landed before Commissioner Frick.

“What the hell is this about your contract?” Frick asked Leja at major-league headquarters.

Leja replied, “I should’ve signed a new contract with an update on the ’54 minimum salary.”

Frick responded, “What the hell are you talking about? They have paid you enough money. Now get the hell out of here and back to the stadium.”

Leja relented, but the Yankees did not forget. The front office stopped communicating with him. “I had the feeling, from that point on, I’m in deep trouble here.”27

In 1954 Leja never started a game. At Fenway Park, Red Sox left fielder Ted Williams said, “Hey Leej! They’re really screwing you, ain’t they?”28

On September 19 Leja was inserted as a pinch runner against the Philadelphia Athletics with none out in the eighth. The Yankees scored four runs and turned over their lineup. With two out in the ninth he singled for his solitary major-league hit.

At spring training in 1955, Stengel observed, “Leja’s a different player this year. He’s more mature, more relaxed around the bag and at the plate. He felt he was excess baggage last season — which he was, of course — but he’s learned a lot.” 29

Leja was joined by another bonus baby, infielder Tom Carroll, as the Yankees allocated a second roster spot to a teenager. Stengel said, “You know, I’ve told both kids they have the same opportunities [Mickey] Mantle had when he made the jump from Joplin [Missouri]. They’ve both got what it takes.” 30

But 1955 was no different. Leja never started a game. In the World Series, the Yankees would not even let him take batting practice.31

Two years. Nineteen games. Ten as a pinch runner. Five as a defensive replacement. Four as pinch-hitter. Seven at-bats. One hit.

Leja said his teammates treated him well, despite practical jokes and ribbing. Upon his arrival at spring training in 1954, he found all of his equipment labeled with dollar signs where his name should have been. Yogi Berra said he wanted to room with “Money” (and he did on the road for two years). Some players called him “The Dude” because he bought $15 sport shirts. “During my two years of bench-warming, my teammates treated me fine,” said Leja. In 1955 they voted him a full World Series share.32

The Yankees’ experiment with Leja ended in 1955. One analysis of the signing and development of bonus babies in the mid-1950s gave the Yankees an “F” for not allowing either Carroll or Leja to play.33

Leja’s demotion to Triple-A Richmond in 1956 at age 20 was expected — but being dropped to Single-A Binghamton and then to Class B Winston-Salem was not. Pitcher Eli Grba, who played with Leja, remembered how clubs handled players who did not conform to team norms. He said, “If you screwed up real bad, even if you hit .310 and had 25 home runs in AAA or AA, they’d send you down.” 34

Leja had 36 homerless at-bats in Richmond, hitting .222. At Binghamton, he hit six home runs with a .242 average in 43 games; with no warning, Leja said, he was demoted again. He went home for a week, then reported to Winston-Salem, where he hit .216 in 65 games. Leja said he was demoralized, and just “went through the motions” for the rest of the season. 35

Back in Binghamton in 1957, still three years younger than his more experienced league peers, Leja emerged as a power hitter. He hit cleanup after right-handed slugger Deron Johnson, hitting 22 home runs and leading the league in RBIs. His nickname was “Iron Liege,” after the thoroughbred that won the Kentucky Derby that year. 36

Leja displayed his fielding prowess, leading Eastern League first basemen in putouts, assists, and double plays.37 Aspiring ballplayers could buy a Rawlings three-fingered Frank Leja mitt called “The Claw.”38 He started a lifelong friendship with a teammate, shortstop Clete Boyer.

The season had its sour moments, said Leja, when the Yankees cut his 1956 salary of $1,500 per month to $500. The front office said the prior poor season plus his annual bonus payment justified the reduction.39 (The bonus was paid in annual installments of $5,000.) After the season Leja married Anne Macarelli, of Nahant, a small oceanfront town in Massachusetts.

In 1958 Leja was promoted to Double-A New Orleans. It was small consolation, because five of his Binghamton teammates were promoted two levels to Richmond. Fellow demoted bonus baby Carroll played half the season in New Orleans as well. He observed, “Frank was a quiet guy and became fairly withdrawn. They didn’t like him and were punishing him.”40

Leja played in every Pelicans game, led the team with 29 HRs and 103 RBIs, and was the Southern Association’s top fielder at first base. His OPS of .866 helped him earn an invitation to spring training with the Yankees in 1959.

Leja was still getting the cold shoulder, though. In St. Petersburg, coach Johnny Neun — a former first baseman himself — was working with players at that position and invited them to ask for help. When Leja stepped forward, Neun said, “Well, if you don’t know how to play the bag by now, you’ll never know.”41

Near cutdown day, Stengel told Leja his hitting and fielding were solid, but he was being sent to Richmond to teach him how to slide.42

Leja hit for power (23 homers) for Richmond, despite Parker Field’s deep fence in right field. 43 He teamed with Johnson to produce one-third of the team’s RBIs. At first base, Grba said Leja was “agile.” 44

On July 25, Moose Skowron broke his arm. Leja remembered the New York press anticipating his callup. Instead, Clete Boyer was promoted and said to Leja, “Jesus Christ, I feel bad for you.”45

While Skowron was out, catcher Elston Howard and Marv Throneberry played first in New York. At the time of Boyer’s callup, Throneberry was hitting .185 with three home runs. After his career, Leja learned that the Yankees refused to trade him to the White Sox in 1959 despite owner Bill Veeck’s offer of cash to repay Leja’s bonus and salary, as well as three AAA players.46 Instead, the pennant-winning “Go-Go Sox” acquired Ted Kluszewski that August.

In 1960, Leja nevertheless said, “I would take the bonus money again.” He noted that it had paid for four years of mental health treatment for his mother.47 He also bought his parents a house and a car, said his son.

A serious hamstring injury in spring training dropped Leja to Double-A Amarillo. He told the Yankees he’d recover faster in Richmond, with its better staff and medical equipment.48 Leja reported to Amarillo reluctantly after staying at home for two weeks, but his injury resulted in a .203 average and one home run in 19 games.

He threatened to go home again, so he was loaned to Nashville, a Double-A affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. After another lackluster 54 games, and continued exasperation, he was loaned and demoted again to the Single-A Charleston White Sox. He hit .211 in 36 games. In Richmond, first baseman John Jaciuk played a full season and hit just three homers with 42 RBIs.

Though Leja’s 1961 contract directed him to report again to Amarillo, he persuaded the Yankees to let him go to spring training with Richmond. He made the team, but sat on the bench. Frustrated again, and ready to quit, he was sold to the Syracuse Chiefs, a Triple-A farm team for the Minnesota Twins.

Rejuvenated, Leja hit 30 homers (second in the International League) with 98 RBIs, posting an OPS of .873. Again, he led the league’s first basemen in putouts, double plays, and assists. But when the Twins wanted to add Leja to their major-league roster, they were blocked. The Yankees said they still owned Leja’s rights.49 He called the commissioner’s office, but Frick refused to help.50 The day before the Yankees opened the 1961 World Series, they traded Leja to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Ahead of the 1962 season, “it seemed as if I had a thousand pounds lifted off my shoulders,” Leja remembered. “I had never enjoyed spring training as much as I did that year. I was hitting the ball real well and picking up Bill White at first base.” He was told he would platoon with White.51 Although St. Louis had traded away Joe Cunningham not long after acquiring Leja, Stan Musial and Gene Oliver could play the position too. The job competition also included Fred Whitfield and another former bonus boy, Jeoff Long.

Thus, 12 days before the start of the season Leja was sold to a second-year expansion club, the Los Angeles Angels. Manager Bill Rigney assured him he would play.52 After 19 games Leja had started four times and was hitless in 16 at-bats. On May 5 he was traded to the Milwaukee Braves. He was sent to Triple-A Louisville and was advised that the Braves would be looking for a replacement for veteran first baseman Joe Adcock after the season.53 Leja hit 20 homers, tied for fourth in the American Association, and was ninth in RBIs despite missing 20 games. His defense at first base earned him the Silver Glove award, given to the top defender at all minor-league levels.

Teammate Phil Roof said, “Leja was a veteran, funny, had a big bat, big swing and was good at first base. I looked up to him as a 21-year-old. He calmed things down.”54

In 1963 the Braves sent Leja to their new top affiliate, Toronto. There he played 97 games and hit .240 with 17 homers. In February 1964, just before spring training, Leja was released at age 28. He started making phone calls and sending letters to major-league teams and one in Japan.55 There was no interest.

“Baseball is strictly a cold, cold business with a bad side I never dreamed of when I was a kid,” he said.56 “If either my ability or my attitude kept me out of the majors, why wouldn’t a single person tell me? I’d rather have someone tell me I’m no damn good than fight the maze of compliments I’ve received.”57

In 1965 the Yankees started the season poorly, and one analysis attributed their decline to the team’s awkward pursuit of bonus babies — using the rule too sparingly, and in the case of Leja (and Carroll), hindering their development.58

In Nahant, where he and his family had made their home, Leja sold insurance year-round. Some days his baseball story was an asset and he was philosophical. At other times he wrestled with his memories. He wore his Yankees 1955 American League championship ring regularly with both pride and disdain, sometimes spitting at it.59

In 1978, Leja said, “I’m convinced I was a marked man with the Yankees because I rebelled a little.”60

Leja and Anne raised their three sons — Frank Carl, Gary, and Eric — in Nahant. The boys shared their father’s passion for competitive sports. Eric played college hockey at the University of Denver.

Frank Carl, the oldest and also left-handed, connected with Eddie Stanky, baseball coach at the University of South Alabama. Stanky, who had been in the Cardinals’ front office when Leja was acquired from the Yankees, offered a scholarship to Frank Carl.

After two years at South Alabama, Frank Carl signed with the Red Sox as a free agent. Although he was released at the end of spring training in 1979, left-handed batting practice pitchers were hard to find, so he was hired to throw batting practice to the Red Sox and visiting teams at Fenway Park.

Gary played college baseball and football at the University of Mississippi and baseball at the University of South Alabama (although Stanky had retired). He was signed as a free agent by the Cardinals in 1988, was invited to spring training, but was later released.

At the 25th reunion of the 1955 Yankees in 1980, as Frank Carl remembered hearing, owner George Steinbrenner assured Leja, “Your career means as much to me as Mickey Mantle’s.” Frank Carl emphasized how much that recognition meant to his father.

In 1982, Leja left insurance sales and founded the L&L Lobster Company. He and his sons hauled traps by hand from the Atlantic Ocean in an open motorboat, which they moored at their bayfront home. “‘I should have gotten into this years ago,’” Frank Carl recalled his father saying. “He was happier selling lobsters.”

Still, 35 years after Leja insisted he was underpaid in 1954, he pursued it again. In 1989 he asked the Major League Baseball Players Association to review his original contract.61 He said that his original inquiry had branded him a “troublemaker,” and it “had a direct bearing on my career.” Upon review, the MLBPA said it appeared he was properly paid.62

Carroll, who started just two games in 1955 and 1956 as a Yankee bonus baby, understood Leja’s frustration about his below-the-minimum contract. “Baseball made up the rules as they went along and would change them when enough owners complained,” he said.63

In 1991, at 55, Leja suffered a fatal heart attack. At the funeral, Clete Boyer sat with Frank’s widow. Leja’s obituaries could not capture his final reflections and how his family tried to come to terms with his bittersweet story.

Just prior to his death, Leja said, “This may sound bitter…It is bitter, but the pleasant memories were playing with the guys. It’s what happened to you as an individual. It’s the business side of it [that was difficult].”64

“The Yankees lied. You never knew who wanted you because they always said, ‘Nobody wants you.’ How the hell do you know who wants you? If they put you on waivers and somebody claims you that they don’t like, then they can take you back off waivers.”65

“So they [the Yankees] ran the whole show. I mean baseball, not just the Yankees, but baseball. It was the same with any organization. That’s what you lived with. You became their pawn and you lived your life the way they told you to live it. So if somebody had a hard-nose for you, they could bury you, and wouldn’t know which end was up,” he concluded. He also revealed that his bonus was not six figures but only $25,000.66

Two decades later, in 2014 the Yankees themselves told Leja’s story, titled “Out at First.” His 1955 teammate, fellow bonus baby Tommy Carroll, confirmed, “Stengel didn’t like him at all. Frank and I were both prisoners…I don’t know what Frank was supposed to do, but whatever it was, he didn’t do it in Casey’s mind.”67

The front office’s dismissive treatment of Leja, said Carroll, was consistent with the personality of General Manager Weiss. “He was a horrible person,” said Carroll, “The most miserable person you’ll ever meet.”68

Stengel said, “They can’t even play once in a while because they don’t know anything except the size of their bank accounts an’ how much the newest cars cost, an’ how fast they are, an’ what town has the biggest steaks. But we gotta keep them on our benches.”69

The story hurt — again — but 60 years later, not in the same way. “He never really spoke about the bitterness unless people asked him about it,” Frank Carl said. “I never felt like he was bitter one day in my life. I think he learned to compartmentalize that part of his life. He kept it very quiet.”70

“I think that my Dad was very proud to have been a major league baseball player, especially a Yankee,” the younger Leja added. “Although it didn’t turn out for him, he was a member of an elite group.”71

And that’s how he will always be remembered. On Leja’s grave marker in Nahant, where he is buried with his wife, engraved in bronze is the interlocked “NY” representing the New York Yankees.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin. It was originally published in January 2019 and was updated in January 2020 with quotes from Tom Carroll.

The author also wishes to thank SABR members Bill Nowlin, Warren Corbett, Dennis Snelling, and Marty Appel for their input and support.

Sources

Books

Snelling, Dennis, A Glimpse of Fame, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (1993): 229-245.

Hemphill, Paul, Lost in the Lights, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press (2009): 151-157.

Kelley, Brent Baseball’s Biggest Blunder, Lanham, Maryland and London, England: The Scarecrow Press (1997): 40-45.

Periodicals

Bromberg, Lester, “To His Hometown Fans, Kid Leja’s All Man,” New York World Telegram, October 13 and 14, 1953.

Bromberg, Lester, “Leja Rates 21-Gun Salute in Home Town,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1954.

Cerrone, Rick, “Out at First,” Yankees Magazine, May 2014: 120-126.

Cline, Brandon, “Past Western Mass. baseball champions dating back to 1936,” Masslive.com, June 11, 2015 (http://highschoolsports.masslive.com/news/article/-2356007778532229896/past-western-mass-baseball-champions-dating-back-to-1936/)

Finn, Gerry, “Frank Leja Reflects Bitterly on a Baseball Career That Never Was,” The Sunday Republican, Springfield, Massachusetts, August 13, 1978.

Grayson, Harry, “What Happened to N.Y. Farm System,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, Edwardsville Intelligencer, Edwardsville, Illinois, May 22, 1965.

Isaacs, Stan, “Leja Asks ‘One Good Shot’ But Nobody Pays Attention,” New York Newsday, March 15, 1960.

Leja, Frank, and Larry Klein, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” Sport, August 1964.

Schwarz, Alan, “The Story Behind the Ring,” The New York Times, April 20, 2009 (reader comment, November 9, 2009).

“Stengel Not Kicking About Leja and Carroll,” Unknown/Baseball Hall of Fame Player File, March 26, 1955.

“Another Gehrig Signed Up by World Champs,” The Era (Bradford, Pennsylvania), October 2, 1953.

Other sources

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Frank Leja.

Frank Leja Uniform Players Contract with New York Yankees, October 1, 1953.

Letter from Frank Leja to MLBPA, August 27, 1989

Letter to Frank Leja from MLBPA, September 27, 1989

Personal Interviews

Tom Carroll, telephone interview, June 1, 2019.

Frank Carl Leja, July 20 and September 29, 2018, along with other brief telephone conversations, email, and text messages.

Eli Grba, telephone interview, September 26, 2018.

Phil Roof, telephone interview, September 22, 2018.

Notes

1 Harry Hanson was 17 years and six months when he played one game in 1913. Leja was 18 years and two months. Rick Cerrone, “Out At First,” Yankees Magazine, May 2014, 120.

2 Wynn Montgomery, “Georgia Phenoms and The Bonus Rule,” Baseball Research Journal, Summer 2010, Society for American Baseball Research (https://sabr.org/research/georgia-s-1948-phenoms-and-bonus-rule).

3 Frank Carl Leja, personal interview, July 20, 2018.

4 Ibid., follow-up telephone interview.

5 Lester Bromberg, “Leja Rates 21-Gun Salute in Home Town,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1954, 5.

6 Frank Carl Leja, follow-up telephone interview, from a phone conversation with his aunt, Leja’s sister.

7 Bromberg, “Leja Rates 21-Gun Salute in Home Town.”

8 Brandon Cline, “Past Western Mass. baseball champions dating back to 1936,” Masslive.com, June 11, 2015

9 Ibid.

10 Bromberg, “Leja Rates 21-Gun Salute in Home Town.”

11 Lester Bromberg, “To His Hometown Fans, Kid Leja’s All Man,” New York World Telegram, October 13 and 14, 1953.

12 Bromberg, “Leja Rates 21-Gu’ Salute in Home Town.”

13 Ibid.

14 Dennis Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (1993): 231.

15 Bromberg, “To His Hometown Fans, Kid Leja’s All Man.”

16 Ibid.

17 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 231.

18 Frank Leja and Larry Klein, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” Sport, August 1964, 40.

19 Snelling, Dennis, A Glimpse of Fame, 232.

20 Bromberg, “Leja ‘Rates 21-Gun’ Salute in Home Town,” 6.

21 “Another Gehrig Signed Up by World Champs,” The Era (Bradford, Pennsylvania), October 2, 1953.

22 Bromberg, “To His Hometown Fans, Kid Leja’s All Man.”

23 Ibid.

24 “Another Gehrig Signed Up by World Champs.”

25 Leja, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” 75.

26 Ibid.

27 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 234.

28 Ibid., 236.

29 “Another Gehrig Signed Up by World Champs.”

30 “Stengel Not Kicking About Leja and Carroll,” Unknown/Baseball Hall of Fame Player File, March 26, 1955.

31 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 237.

32 Leja, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” 76.

33 Brent Kelley, Baseball’s Biggest Blunder, Lanham, Maryland and London, England, The Scarecrow Press (1997): 40-45. In 1955 and 1956 Carroll started one game, appearing in 49 others as a pinch hitter, pinch runner, or defensive replacement.

34 Eli Grba, telephone interview, September 26, 2018 (hereafter Grba interview).

35 Leja, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” 76.

36 Alan Schwarz, “The Story Behind the Ring,” The New York Times, April 20, 2009 (reader comment, November 9, 2009).

37 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 242-43.

38 Worthpoint.com, Frank Leja Rawlings Model T107.

39 Leja, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” 76.

40 Tom Carroll, telephone interview, June 1, 2019.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 It was 365 feet down the right field line at Parker Field through 1962, according to the field’s Facebook page. Leja said it was 395 feet to right center (Leja, “The Bad Side of Baseball,” 76). He hit 20 of his 23 home runs on the road (Isaacs, “Leja Asks ‘One Good Shot’ But Nobody Pays Attention”).

44 Grba interview.

45 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 238.

46 Ibid., 238-9

47 Isaacs, “Leja Asks ‘One Good Shot’ But Nobody Pays Attention.”

48 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 239.

49 Ibid., 240.

50 Gerry Finn, “Frank Leja Reflects Bitterly on a Baseball Career That Never Was,” The Sunday Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), August 13, 1978.

51 Leja, The Bad Side of Baseball, 76.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Phil Roof, telephone interview, September 22, 2018.

55 Leja, The Bad Side of Baseball, 38.

56 Ibid., 40.

57 Ibid., 77

58 Harry Grayson, “What Happened to N.Y. Farm System,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, Edwardsville (Illinois) Intelligencer, May 22, 1965.

59 Leja, The Bad Side of Baseball, 77.

60 Finn, “Frank Leja Reflects Bitterly on a Baseball Career That Never Was.”

61 Letter from Frank Leja to MLBPA, August 27, 1989.

62 Letter to Frank Leja from MLBPA, September 27, 1989.

63 Tom Carroll, telephone interview, June 1, 2019.

64 Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, 237.

65 Ibid., 229.

66 Ibid.

67 Cerrone, “Out At First,” 124.

68 Tom Carroll, telephone interview, June 1, 2019.

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid., 126.

71 Ibid.

Full Name

Frank John Leja

Born

February 7, 1936 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

Died

May 3, 1991 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.