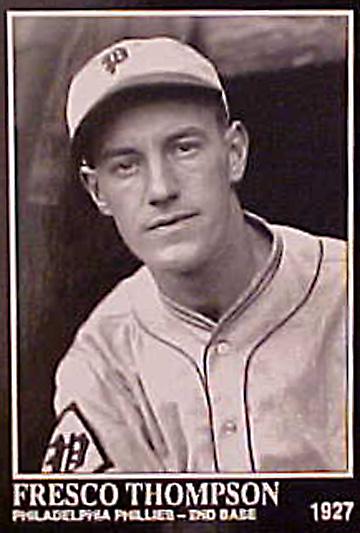

Fresco Thompson

Fresco Thompson, the jester in Walter O’Malley’s court, ran baseball’s most productive scouting and player development factory during the 1950s and 1960s. With O’Malley providing the money, Thompson and his scouts providing the players, and vice president Buzzie Bavasi molding the roster, the Dodgers won eight pennants and four World Series between 1952 and 1966, more than any team except the Yankees.

Fresco Thompson, the jester in Walter O’Malley’s court, ran baseball’s most productive scouting and player development factory during the 1950s and 1960s. With O’Malley providing the money, Thompson and his scouts providing the players, and vice president Buzzie Bavasi molding the roster, the Dodgers won eight pennants and four World Series between 1952 and 1966, more than any team except the Yankees.

They did it almost entirely with homegrown talent. When Brooklyn won its only championship in 1955, all but four of the 22 players who appeared in the World Series had originally signed with the Dodgers. On the last pennant winner in that period, in 1966, eight of the top 10 position players and three of the four regular starting pitchers were products of the organization.

On Thompson’s watch, the Dodgers developed five Rookies of the Year, more than any other team: Joe Black (1952), Jim Gilliam (1953), Frank Howard (1960), Jim Lefebvre (1965), and Ted Sizemore (1969). The scouts found Hall of Famers Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Don Sutton. Homegrown Dodgers captured six MVP awards: three for Roy Campanella and one each for Don Newcombe, Maury Wills, and Koufax. Pitchers won five Cy Youngs: Newcombe, Drysdale, and three for Koufax.

Overshadowing his skills as an administrator and judge of talent, Thompson was best known for his ready wit and the stories he told. He said Willie Davis was “so fast he can beat out a pop fly.” When a young player complained that he was swinging a fraction of an inch under the ball, Thompson advised him to put insoles in his shoes to lift himself up.1 A marginal ballplayer, Thompson became a star on the banquet circuit. His wife, Peg (the former Margaret Kemmy), saw a newspaper article advertising her husband’s appearance before a civic club with a photo captioned, “Agrees to speak.” She commented, “That’s the greatest understatement I ever heard.”2

Thompson’s paternal grandmother found the name “Fresco” in a Scottish novel and bestowed it upon her son, Lafayette Fresco Thompson. He passed it on to his son, who was born to the former Jessica Irene Fancher on June 6, 1902, in Centreville, Alabama. L.F. Thompson Sr. started as a shoe salesman and rose to be an executive with the J.C. Penney department-store chain, moving the family to Chicago and then New York.

Young Fresco was the captain of the New York City championship baseball team at George Washington High and went to Columbia to play baseball and football. As a 5-foot-8, 136-pound quarterback on the freshman team, he was dwarfed by fullback Lou Gehrig. Thompson had little interest in school, and flunked out after a year.

He wanted to play professional baseball, but scouts ignored him. He wrote letters to teams and got a nibble from the Class-D club in Grand Island, Nebraska, offering him a job if he would pay for his own bus ticket. He joined the team as a second baseman in 1923.

Two years later he got his first trial in the majors in a September call-up by Pittsburgh. When the Pirates sent him back to the minors the next spring, a local paper reported, “Lafayette Fresco Thompson, with all of his names, was shipped to Buffalo today.”3 The Giants tried him out in September 1926. Thompson liked to say that he hit .625 (5-for-8) but manager John McGraw traded him away. “They brought in a pretty good man to replace me. Rogers Hornsby was no slouch.”4

The trade sent Thompson to the Philadelphia Phillies and the bottom of the National League. He described his time with the Phils as “four years of living death.”5 They were his only seasons as a regular player, but the club lost more than 100 games three times out of four. The home field, Baker Bowl, was a comical excuse for a ballpark with its 279-foot right field wall. The park made right fielder Chuck Klein a Hall of Famer and Thompson a .300 hitter.

Manager Burt Shotton named Thompson the team captain, and the little second baseman was the “holler guy” of the infield. When a teammate saw him gargling with mouthwash in the clubhouse, he explained, “Just getting in shape for the game.”6

In 1930, the year of the rocket-powered baseball, the Phillies batted .315 but lost 102 games with perhaps the worst pitching and defense ever to disgrace a major league diamond. As captain, Thompson delivered the lineup card to the umpires. When he handed in a lineup showing “P: Willoughby and others,” umpire Bill Klem accused him of making a travesty of the game. “I’m not,” he replied, “but our pitchers are.”7 Thompson wasn’t much help to the feckless flingers; he was an erratic fielder, finishing first or second in the league in errors every year he was in Philadelphia.

Traded to Brooklyn after the 1930 season, Thompson shared a spring-training locker with slugger Babe Herman, who complained, “What’s the idea of me dressing with a .250 hitter?” Thompson told him, “How do you think I feel, dressing with a .250 fielder?”8

Brooklyn Eagle writer Tommy Holmes described the new second baseman as “a wideawake little bird with a disarming smile and a constant stream of chatter” who would liven up the Dodger infield.9 Manager Wilbert Robinson disagreed; he hated the trade. The front office had given up one of Uncle Robbie’s favorite pitchers, Jumbo Elliott, and brought in an awful left fielder, Lefty O’Doul, to go with the awful right fielder, Herman. Both were elite hitters, but with that pair planted in the outfield corners, center fielder Johnny Frederick needed a motorcycle.

Robinson consigned Thompson to the bench and stuck with the holdover second baseman, Neal Finn. After a year as a part-time player, Thompson began a tour of the high minors, with stops in Jersey City, Buffalo, Montreal, and Minneapolis.

In 1938 he switched to managing and continued his travels in Birmingham, Hartford, Williamsport, Reading, Johnstown, Montreal, and New Orleans. He finally got off the treadmill during World War II, becoming an assistant to Dodgers farm director Branch Rickey Jr. and a troubleshooter and scout for President Branch Rickey Sr.

Thompson called his apprenticeship with Rickey Sr. “a concentrated baseball education under the tutelage of a master.”10 The association led to a front-office career with the Dodgers that lasted the rest of his life.

With automakers building tanks and planes, no new cars were available in wartime. Rickey complained that he needed a new Ford. “I’d like to get a Cadillac,” Thompson said. Rickey asked, “How can you afford a Cadillac on your salary?” Thompson told him, “If I have to get along without a car, I’d rather get along without a Cadillac than a Ford.”11

The Rickey era in Brooklyn ended in 1950 when O’Malley, the Dodgers legal counsel and a minority owner, bought Rickey’s stock and took control of the franchise. Writers covering the team assumed Thompson would become general manager; the Brooklyn Eagle’s Tommy Holmes called him “the logical choice.”12 Instead, O’Malley divided the job. He put Buzzie Bavasi, the general manager of the top farm club at Montreal, in charge of the major-league roster and the two Triple-A teams, while Thompson ran the rest of the two dozen farm clubs and the scouting staff. They had equal rank as vice presidents, but neither held the title of general manager.

L to R: Buzzie Bavasi, Walter O’Malley, Fresco Thompson, 1950.

Announcing the appointments, O’Malley said, “All of us will make decisions together.” There was no question who would have the last word; O’Malley had sunk most of his money into the team and intended to be an active president. “Fresco and Buzzy are good friends,” he said. “Each knows what the other can do and they respect each other’s judgment.”13

Bavasi was not quite 36 years old, a dozen years younger than Thompson, and like Thompson he was a New Yorker from a well-to-do family (he once offered to lend O’Malley money). He had had only two employers since college: the Dodgers and the U.S. Army. Hired by the Dodgers on the recommendation of his college roommate’s father, National League president Ford Frick, Bavasi learned baseball from the bottom up, starting as a Class-D general manager. Like Thompson, he was a Rickey man to the core.

Rickey took several of his disciples along to his new job with the Pittsburgh Pirates, but Thompson and Bavasi, seeing their opportunity in Brooklyn, transferred their loyalty to the new owner. It was said that the Protestants went with Rickey, and the Catholics stayed with O’Malley.

The team belonged to O’Malley, but Bavasi and Thompson ran the Dodgers according to Rickey’s principles. “Out of quantity comes quality,” Rickey preached, and the club signed boatloads of young players. Scouts looked first of all for running speed and strong arms. “If a boy cannot run and throw at 18, he won’t at 20,” Thompson said, “but if he can hit without apparent faults in high school, maybe he will later. No one can say for sure.”14

To illustrate the uncertainties of scouting, he often named players the Dodgers could have signed, but didn’t: Willie Mays, Ernie Banks, Phil Rizzuto, Hank Greenberg, and Whitey Ford, whom Thompson rejected because the young lefty didn’t throw hard enough.15

Thompson said the Brooklyn farm system, with as many as 500 players, produced around a dozen each year who were major-league ready. That was more than the parent club needed, so he and Bavasi sold the surplus to help defray the cost of the huge organization. While Pee Wee Reese and Maury Wills held down the shortstop job for more than a quarter-century, a Dodger diaspora of shortstops spread around the league: Chico Carrasquel, Billy Hunter, Bobby Morgan, Chico Fernandez, Don Zimmer, and Bob Lillis. For several years in the 1950s, the Dodgers had sent more products to the majors than any other team.

The club also ran a farm system for managers. Zimmer, Dick Williams, Sparky Anderson, Gil Hodges, and Gene Mauch all started their playing careers in the Brooklyn organization.

Thompson believed a young player needed at least four years in the minors, but the Dodgers didn’t hesitate to make exceptions for exceptional talents such as Don Drysdale, Don Sutton, Willie Davis, and Tommy Davis. A blackboard covering one wall of Thompson’s office listed every player in the system, along with his personal grade of each one’s potential.

When the players gathered every year at the Vero Beach spring training complex, he distributed questionnaires to all. To the question “State of health?” one boy answered, “Pennsylvania.” “Length of residence?” “About 40 feet.”16

Thompson and Bavasi’s loyalty to their boss was a two-way street. O’Malley set a budget and managed business affairs, and trusted his two vice presidents to run baseball operations without interference. When the club needed a new manager for 1954, O’Malley approved Bavasi’s choice of an unknown minor league pilot, Walter Alston. A few years later the owner wanted to fire Alston after a second-place finish, but he let Bavasi talk him out of it. Bavasi and Thompson worked on one-year contracts, like the manager. O’Malley had a reputation for paying low salaries, but offering generous perks including profit sharing and a pension plan, a rarity in baseball front offices.

The Dodgers won four pennants and the 1955 World Series in the first six years of the O’Malley regime. Most of the key players #— “the Boys of Summer” — were holdovers from Rickey’s time. The retooling of the roster began after baseball’s winter meeting in 1957, when the majors scrapped the infamous bonus rule that required any young player who got a bonus over $4,000 (such as Sandy Koufax) to spend two years on the big-league roster. Now that the raw youngsters could be farmed out, Bavasi and Thompson persuaded O’Malley to open his checkbook. Even as he faced the expense of moving to Los Angeles, the owner authorized $800,000 in bonuses in 1958 and $900,000 in 1959.

Over the next two years the Dodgers signed more than 100 players, including Ron Fairly, Willie Davis, and Frank Howard. Chief scout Al Campanis and his staff chose wisely, and Thompson’s player development organization turned many of the prospects into useful major leaguers. The spending splurge helped make the 1960s another successful decade.

With the move to Los Angeles, Bavasi was at last given the title of general manager, and Thompson reported to him. But the historic move was a rocky ride. O’Malley, in a rare intrusion into baseball decisions, told Bavasi and Alston to play the famous Dodger veterans in the first year in their new home. He feared Southern California fans wouldn’t turn out to watch a lineup of no-name rookies. The aging Boys of Summers Past fell to a shocking seventh-place finish in 1958.

O’Malley had bigger problems. Los Angeles politicians proved unable to deliver on their promises, and the Dodgers owner had failed to do due diligence. He learned, too late, that the city council’s pledge to provide land for a new stadium could be overturned in a referendum. O’Malley told Bavasi, Thompson, and other executives to hold off on buying homes in California until the issue was settled. Even after voters approved the Chavez Ravine land deal in June 1958, lawsuits put up more roadblocks. Once the legal issues were decided in the Dodgers’ favor, city agencies — planning, zoning, permitting, inspecting #— moved at a glacial pace. Each delay ran up the cost of construction.17

Thompson later said he and Bavasi expected the new stadium to be ready in 1959 or 1960. They knew it was designed to be a pitcher’s park, so they began building the roster around pitching and speed.18 But they were stuck in the humongous Los Angeles Coliseum for four years. It was a football stadium surrounded by a running track, with a ridiculously short left-field fence that rewarded home run power and was tough on pitchers. It also had no roof and no beer.

But the farm system powered a turnaround on the field. In mid-1959 the Dodgers called up pitchers Roger Craig and Larry Sherry and shortstop Maury Wills. Those three #— none of them highly regarded prospects — were key contributors in a dramatic stretch drive that gave the Dodgers their first pennant in Los Angeles and a World Series championship.

The victory marked a changing of the guard from Rickey’s players to those acquired by Bavasi, Thompson, and Campanis. With younger players moving in, the team tied for first place in 1962, the first year in Dodger Stadium, only to lose to the Giants in a playoff. More pennants followed in 1963, 1965, and 1966.

Thompson’s farm system was shrinking steadily as many minor leagues folded, killed by television and demographic changes. From 24 teams when he took over in 1950, his domain dwindled to eight by 1963. That added to his challenges. With so few roster spots, it’s likely that he would have had no place for a Maury Wills, who had stalled in the minors for eight years, or a Roger Craig, a former big leaguer who was hanging on in Triple A while he recovered from a sore arm. The Rickey approach — quality out of quantity #— was obsolete.

Thompson believed the new generation of players was unwilling to serve a long minor-league apprenticeship; they were likely to move on to another job if they didn’t move up fast. Like many other old-timers, he also believed modern players weren’t as tough as their predecessors: “Nowadays a case of dandruff will put a player on the bench for several days.”19

The Dodgers organization under O’Malley was unique for its stability. Most famously, Alston managed the club for 23 seasons on one-year contracts. The tandem of Bavasi and Thompson ran the baseball operations for 18 years in apparent harmony. Both wrote memoirs, but neither provided any insight into how they worked together. Bavasi commented only that Thompson was “the man who kept things upbeat, kept people smiling.”20

Their partnership ended in 1968 when Bavasi, with O’Malley’s blessing, accepted an offer to be part owner and president of the expansion San Diego Padres. At 66, Thompson was named GM of the Dodgers.

Just three months later, he became ill with cancer. He underwent three operations, including one to remove a kidney, before he died on November 20, 1968. O’Malley continued to send pension checks to Thompson’s widow, Peg, for years.

The Rickey influence over the Dodgers continued with the promotion of Al Campanis to general manager, a job he held until 1987.

Acknowledgments

Photo Credit: Conlon Collection/The Sporting News

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel.

Notes

1 Joe Hendrickson, “Diamond Distinction,” Pasadena (California) Independent, November 22, 1968: 14.

2 “Fresco Thompson, Dodger G.M., Ex-Scout and Player,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1968: 44.

3 United Press International, “Fresco Thompson Is Dead at 66,” New York Times, November 21, 1968: 47.

4 Hendrickson, “Diamond Distinction.”

5 Thomas Holmes, “Thompson’s Tabasco Livens Brooklyn’s Seasoned Infield,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 31, 1930: 24.

6 Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1968: 32.

7 Jim Murray, “Baseball Al Fresco,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1962: III-1.

8 Bob Nitsche, “Baseball Won’t Be the Same with Fresco Thompson Gone,” Reno (Nevada) Gazette-Journal, November 22, 1968: 14.

9 Holmes, “Thompson’s Pepper Should Give Robins Livelier Appearance,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 16 1930: 28.

10 Fresco Thompson with Cy Rice, Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle (New York: David McKay, 1964), 74.

11 Ibid., 59.

12 Holmes, “Scatter Shot at the Sports Scene,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 23, 1950: 15.

13 Harold C. Burr, “O’Malley Holds Reins on Bavasi and Thompson,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 3, 1950: 21.

14 Dave Lewis, “Once Over Lightly,” Long Beach (California) Independent, March 22, 1961: C-1.

15 George Lederer, “Mays, Ford, Banks Nixed by Dodgers,” Long Beach (California) Independent Press-Telegram, March 5, 1961: C-3.

16 United Press International, “Fresco Thompson Is Dead at 66.”

17 Information about the move to Los Angeles comes primarily from Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers, & Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

18 Ibid., 266.

19 Nitsche, “Baseball Won’t Be the Same.”

20 Buzzie Bavasi with John Strege, Off the Record (Chicago: Contemporary, 1987), 83. Bavasi’s book and Thompson’s Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle are full of amusing stories but little substance.

Full Name

Lafayette Fresco Thompson

Born

June 6, 1902 at Centreville, AL (USA)

Died

November 20, 1968 at Fullerton, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.