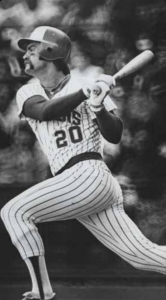

Gorman Thomas

He was the first amateur player selected by his expansion franchise and became its first home-run champion, alas, when the parent team was in a different city. In his major-league debut, he dropped the first ball hit to him for an error and got his first hit, a triple, in his second at-bat. Nine days later, he hit his first home run, off a future Hall of Famer. Gorman Thomas became one of the franchise’s all-time fan favorites.

He was the first amateur player selected by his expansion franchise and became its first home-run champion, alas, when the parent team was in a different city. In his major-league debut, he dropped the first ball hit to him for an error and got his first hit, a triple, in his second at-bat. Nine days later, he hit his first home run, off a future Hall of Famer. Gorman Thomas became one of the franchise’s all-time fan favorites.

James Gorman Thomas III was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on December 12, 1950, to James Gorman Thomas Jr. and Gladys (Altman) Thomas. He had a brother, Gary, and a sister, Deborah. His father was a World War II veteran, and a postal worker who retired as a postmaster. He also preceded Thomas in professional baseball, having signed with the New York Yankees.1 Gladys was a homemaker and active in her church.

Gorman’ interest in baseball started early, in Little League baseball. He went on to the Pony League, the Colt League, and American Legion ball, making the all-star teams in each of the 11 years he played at those levels. His Pony and Colt League teams won state championships.2

At Cardinal Newman High School in Columbia, South Carolina, Thomas earned 14 letters in baseball, football, basketball, and track3 and led the basketball team to three titles.4 After his family moved to Charleston, Thomas enrolled in James Island High School for his senior year and led the football team to a 15-0 championship season.5 Turning to baseball, he pitched and played shortstop with scouts in attendance noting his power potential.6 Hitting .430, he was first-team All-Conference at shortstop and was named a High School All-American.7

On June 5, 1969, Thomas became the first player drafted by the expansion Seattle Pilots8 in the amateur draft.9 Forgoing a football scholarship with Florida State University,10 he joined the Billings Mustangs in the rookie Pioneer League, batting .296 in 41 games with 26 errors at shortstop. As he told Mario Zino in 2013, “I played the position like a hockey goalie. It was like I was fending off slap shots.”11

After the season, the Pilots went bankrupt and re-emerged in 1970 as the Milwaukee Brewers. Thomas spent the 1970 and 1971 in the Class-A Midwest League. Playing for Clinton (Iowa) in 1970, he struggled, batting .212 and making 28 errors in 85 games. At Danville (Illinois) in 1971 he moved to the outfield, and both his hitting and fielding improved and he hit a league-record 31 home runs12. (He also led the league with 170 strikeouts in 121 games.) Promoted to Double-A San Antonio in 1972, he won another home run title, swatting 26, while his 171 strikeouts also topped the league.

A few weeks into 1973 spring training, Brewers manager Del Crandall named the young slugger his starting right fielder.13 His major-league debut, on Opening Day at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, started poorly: He dropped the first ball hit to him for an error. He tripled14 in his second at-bat. In the first game of an April 15 doubleheader at County Stadium, Thomas smashed his first home run, in the bottom of the ninth inning off Jim Palmer, forcing extra innings in a Brewers 11-inning 3-2 victory. But on July 2 with only 27 hits, and a slash line15 of .213/.281/.307 including 52 strikeouts, the struggling outfielder was demoted to Triple-A Evansville, missing a $6,500 progress bonus by two days.16 Thomas was recalled when rosters expanded in September and was 2-for-28, including his second home run, but batted only .187 overall.

Thomas returned to the minors in 1974 with Sacramento of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. Playing in Hughes Stadium, which had with a very short left-field wall,17 he hit 51 homers, batted .297, and set a PCL strikeout record, fanning 175 times.

Thomas was considered a flake.18 He was out of minor-league options but the club was reluctant to part with him because of his power potential. Crandall considered him “excess baggage”19 but the club decided to keep him on the 1975 roster. Thomas rode the pines as an occasional defensive replacement until Crandall decided to platoon him in center because “[h]e had a good attitude and worked hard.”20 Thomas started strong but was removed from the starting lineup when he went into a severe slump.21 Thomas hit only .179 in 240 at-bats with 84 strikeouts.

Again in 1976 Thomas began the season on the bench, until the starting center fielder Sixto Lezcano faltered and new manager Alex Grammas, saying, “I just think he has too much talent to sit around,”22 put him in the lineup. When the Brewers acquired another center fielder, Von Joshua23 on June 2 he returned to his bench role until early August, when Grammas shuffled his outfield, inserting Thomas in center for every game until he injured his left shoulder making a diving catch on August 30 and his season was over. It was Thomas’s second consecutive season with a sub-.200 batting average (.198).

After spring training in 1977 the Brewers gave up on Thomas, demoting him to Triple-A Spokane. General manager Jim Baumer explained: “Lack of contact. He’s had that problem all his life.” Thomas considered it a “blessing in disguise,” saying, “A good season with Spokane could give me another chance.”24 Thus motivated, he had his best year so far. He topped .300 for the first (and only) time with 36 home runs and 114 RBIs. His second chance came true on October 25 when he was dealt to the Texas Rangers to complete an August trade. Also in October, Thomas and Debbie Hansen of Milwaukee were married, “putting his life in some order.”25

The Brewers purchased Thomas’s contract from the Rangers on February 8, 1978, stirring speculation that the transaction had been prearranged to free a roster spot for the Rangers in a pennant race and find a way for the Brewers to keep their slugger. All parties denied the speculation.26 But 30 years later, MLB.com reported that Milwaukee’s Baumer had asked his Texas colleague for a favor. Texas GM Dan O’Brien recalled, “It was purely a friendship deal.” The Rangers hid the slugger on their roster so the Brewers could bring him back, circumventing the option rules.27

Harry Dalton, hired from the Angels to be the Brewers GM after a front-office cleanout,28 named George Bamberger, Baltimore’s pitching coach, as the Brewers’ manager. Bamberger wanted Thomas to be his center fielder. All the manager asked him was hit .250, to which Thomas replied, “I can hit better.”29 The prodigal slugger credited Spokane manager, John Felske for working with him daily and batting him fifth every day, building his confidence.30 Thomas said he had learned a valuable lesson from Felske: “Don’t try to hit taters on every swing.”31 Fortunately for Thomas, Bamberger preferred a strikeout over a double play. The more relaxed slugger had a big season, challenging for the home-run lead into August. He batted .246 with 32 homers and 86 RBIs. The free swinger still struck out 133 times but drew 73 walks for a respectable .351 on-base average. And the Brewers had their first winning season, 93-69, finishing third.

Thomas’s nickname, Stormin’ Gorman, was given to him by Brewers coach Frank Howard. Asked why, Thomas said, “When a guy who is 6-feet-8 and 300 pounds gives you a nickname, you don’t ask why.”32

Thomas batted cleanup for much of the 1979 season, again hitting for power while fanning often but not concerned. “Strikeouts are overrated,” he said. “Even batting average is overrated. The only thing that means anything is RBIs. That means you’ve done something to help your club win the game.”33 Bamberger wouldn’t pinch-hit for him saying, “You never know when he’s going to hit one out and he bears down more with men on base.”34 He had dry spells (2-for-38 and 0-for-24) and hot streaks like June’s 14-game hitting streak, slugging five homers with 20 RBIs and August’s six homers in seven games. Thomas was proud of his one consistent trait: strong, hard-nosed defense. He had 435 outfield putouts in 1979. He was knocked out of games four times during the season after running into walls.35 He led the AL with 45 home runs; his 37th round-tripper, on September 2, set a franchise record. Bamberger considered benching Thomas on the season’s last day when he was one strikeout shy of the league record. The free swinger replied, “No way, I sat on the bench too long.”36 In the eighth inning, a called third strike tied Dave Nicholson’s 1963 American League record of 175.37 For the season, Thomas slashed .244/.356/.539 and finished seventh in the AL MVP balloting. His 123 RBIs and 98 walks were also franchise records. What changed? Said Dalton: “It’s hard for management to be tolerant of a player and give him total commitment when the player doesn’t bring 100 percent of himself to the park.” And Thomas agreed: “I used to be terrible, I’d stay out all night, then turn around and hunt or play golf all day.”38 The Brewers finished second in the AL East with a 95-66 record.39

Going into the 1980 season, Thomas and the Brewers anticipated a pennant after finishing third and then second. Bamberger was out until midseason after having a heart attack during spring training, and was replaced by third-base coach, Buck Rodgers. Through most of May, Thomas was hitting below .200 with only eight home runs and 49 strikeouts, and bouncing around the batting order. When Bamberger returned on June 6, he returned Thomas to the cleanup spot and the slugger responded with a hitting streak. On July 2 he belted his 17th homer and became the Brewers’ all-time leader with 116.40 He was a fan favorite, blue-collar like the hard-working Milwaukeans, whom he appreciated because “They know when to cheer and they know when to boo. And they know when to drink beer. They do it all of the time.”41 In a Sporting News poll of players and media for an all-hustle-team, Thomas was one of the three AL outfielders selected. “He knows every wall in the league” and plays hurt, said the paper.42 True to form, the gamer played in all 162 games in 1980, swatted 38 homers, had 105 RBIs, and led both leagues with 170 strikeouts. For the Brewers, though it was a disappointing year: They slipped to third place with 86 victories.

The offseason involved thorny contract negotiations with Thomas, who was potentially a free agent after 1981. In January, the Thomases welcomed their first child, daughter Kelly. In March, he signed a five-year contract for $3 million. But baseball and Thomas faced challenges in 1981. Bamberger retired and Rodgers, who succeeded him, was uncertain who would be his cleanup hitter. He also asked Thomas to move to right field to make room for Paul Molitor in center. By the end of spring, training, the proud defender questioned the moves: “I think I proved myself playing center field, offensively and defensively. So why make the change? Why not move Molitor to right field and leave me in center.”43 He told Peter Gammons, who considered Thomas the most underrated center fielder in the league, “I’m two steps quicker in center field than I was in right. In center, I don’t have to think, I just react.”44 Thomas started strong and with oft-injured Molitor on the disabled list, he played more in center and was leading the AL with 15 homers on June 12, when the players walked out for the first midseason strike in major-league history.

A settlement was reached on July 31 with the season’s second half resuming on August 10 with another level of playoffs added with each half’s division winners meeting in the first round. After a disappointing third-place finish when the strike began, it was a new opportunity for the Brewers. Thomas was chosen for his only All-Star Game,45 played on August 9, popping out as a pinch-hitter. He was thrilled with being selected. “I really enjoyed this,” he said. “I waited a long time. I would have liked to have gotten another chance to hit, but that’s not the way the game is set up. I was happy to get one at-bat.”46

Thomas played center more in the second half with Molitor’s continuing injury problems, becoming permanent in September. Although his second-half production fell off, his sacrifice fly on October 3 against Detroit proved to be the game-winner and clinched the Brewers’ first trip to the postseason. Asked after the game if the title meant less due to the split season, he replied, “They can say what they want. I’m going to the playoffs. That’s all I care.”47 Thomas’s power numbers slipped that season but the .259 batting average was his best in the majors. His 85 strikeouts were only fourth in the AL and he never led that futile category again.

Facing the New York Yankees48 in the Division Series, The Brewers lost Games One and Two at home as Thomas went hitless with five strikeouts. They tied the series in New York, winning Games Three and Four. Thomas hit a solo home run in Game Five but the Yankees won the game and the series. Thomas was 2-for-18 with nine K’s in the series.

Thomas was anxious for the 1982 season49 and a return to the playoffs, knowing he was the starting center fielder with the Molitor experiment over. He didn’t hit his first homer until May 1 and was part of the team’s May slump when the Brewers lost 14 of 20 and fell to fifth place. He injured his shoulder in late May and missed five games. While he was out, Dalton replaced Rodgers with hitting coach Harvey Kuenn, saying “[T]he chemistry had gone sour and the performance level of the team was not up to the expectations we have with the talent here.”50 Kuenn’s philosophy was different: “I like the club to be loose, have a laugh. Go out and play the game and have fun.”51 The free-spirited Thomas welcomed the new philosophy, saying, “Everyone is loose. Just go out and have a good time.”52 Thomas got hot, topping the league with 22 home runs by the All-Star break. He was named AL Player of the Week for the week of August 9 after hitting five home runs to retake the AL lead with 32.53 Injuring his elbow throwing to the infield for a double play on September 5, Thomas doubled over in pain but continued playing, holding the arm stiff and close to his body. After the game, he visited the team physician in a great deal of pain; he had reaggravated an earlier injury suffered making a diving catch.54 He received a cortisone shot and after taking just one day off, he did not miss a game the rest of the season. But Thomas struggled after the injury, going, seven consecutive September games without a home run and finished the final week’s stretch run without a homer or RBI. (He still shared the AL homer title with Reggie Jackson and had 100-plus RBIs for the third season in a row.) The season went down to the wire with the Brewers winning their first division title in the season finale. Thomas was excited about playing, saying, “Damn, this is why I love this game. Down to the last moment. I love it.”55

Entering the AL Championship Series, Thomas was in a 0-for-16 slump that ended immediately when he homered in his first at-bat against the California Angels. That was his only long ball in 46 postseason plate appearances and his only hit in the ALCS. He injured his right knee with an awkward slide in Game Four and was limping badly before Sunday’s decisive contest, but the gamer started, then watched the dramatic seventh-inning rally from the bench after grimacing in pain grounding out to end the sixth inning. The Brewers victory propelled them into their first World Series in 25 years.56

The World Series opened in St. Louis and Thomas was a doubtful starter after the ALCS injury. The resilient trouper wanted to play, saying, “It’s no better than 50 percent. But I’ve got to play. You don’t play 168 games and take a day off.”57 Playing center field in all seven games, he had minimal impact. In Game Three, with the Series tied, a record County Stadium crowd of 56,55658 saw his seventh-inning single end a 1-for-23 slump; in the ninth inning he was robbed of a home run by St. Louis center fielder Willie McGee’s leaping catch as the Cardinals won. With the Brewers trailing 5-1 after six innings in Game Four, Thomas’s single drove in the final two runs in a six-run seventh-inning rally for a 7-5 victory, tying the Series. That game-winning hit and RBI were his last in the Series; he was hitless in the final three games. The Brewers took a 3-2 Series lead and needed only one victory to win the Series in St. Louis but they ran out of steam and lost the Series in seven games. Thomas ended Game Seven and the Series by striking out with two men on base. In 26 at-bats, he had just three singles and three RBIs.

During the offseason, Thomas finished eighth in the MVP vote and was selected to The Sporting News 1982 American League All-Star Team.59 The Brewers shopped Thomas at the winter meetings; Dalton was a proponent of the Branch Rickey theory “It’s better to unload an aging player one year too early than one year too late.”60 But there were no takers. The slugger had arthroscopic knee surgery to clean up the injury that affected his World Series performance. Also, son Justin was born on January 9.

Thomas’s 10th major-league season, 1983, had a new challenge: a June trade to Cleveland. He had been below .200 most of the season. (His third home run of the campaign, on May 6, was his 200th.) All changed on June 6 when Dalton swapped starting center fielders and pitchers with Cleveland, obtaining Rick Manning for Thomas. Thomas was devastated. “I hate to even think about leaving Milwaukee” he said. “Milwaukee’s my home. I love the people.”61 The feeling was mutual with fans bombarding the Brewers switchboard and talk shows with their shock and disappointment. As fate would have it, he returned as an Indian 18 days later with nearly 135,000 ecstatic fans welcoming their hero home for a weekend series. He received a standing ovation leaving the dugout for batting practice and when his picture appeared on the scoreboard. The center-field bleacher fans shouted repeatedly “Gor-man” when he went to his position.62 There were signs and posters everywhere. And the fans were relieved that their struggling Brewers swept the series with Thomas going 1-for-10, the one hit a solo homer. He played with aches and pains and struggled, batting mostly in the low .200s and ending with 17 homers in 106 games with Cleveland. As a player traded in the middle of a contract, Thomas exercised his right to demand a trade and was dealt to the Seattle Mariners on December 7.63

Drafted by a Seattle team, Thomas finally played for one in 1984. He was reunited with his new skipper, Del Crandall, who considered him excess baggage in 1975. Diagnosed with a torn right rotator cuff during spring training, Thomas was determined to play through the pain: “Let’s take two aspirins and go get ’em.”64 After his arm went numb following a diving catch on May 15,65 he finally succumbed to the pain going on the DL. A complete tear of the rotator cuff was discovered during surgery on June 8 with doctors unsure if he would play again. His season was over after 35 games with one homer and 13 RBIs.

Determined to come back, Thomas reported to spring training in 1986 without a glove per doctor’s instructions to make sure he didn’t even think about picking up a ball.66 The comeback was accomplished: He was the Mariners’ DH in 135 games, batting cleanup, and playing nearly every day. His first homers, three, including a grand slam, came in the third game of the season, driving in six runs. In Milwaukee in July, he smashed two home runs and was cheered by his fans twice, leaving the dugout to tip his cap. He got a standing ovation the next day after another home run.67 As he had done throughout his career, he was hot with homer binges and cold with hitless streaks. The 1985 American League Comeback Player of the Year batted only .215 but hit 32 home runs.

Thomas received a 1986 contract offer with a 20 percent cut in pay,68 which he rejected; eventually he reluctantly agreed to a $650,000 nonguaranteed contract because the club wasn’t sure the repaired shoulder would hold up.69 He started the season batting .289 and slugging .578, then slowly cooled off, striking out almost daily. Thomas lost playing time when Dick Williams became manager on May 9 and he was released on June 25. “We weren’t getting any production from Gorman so he became expendable,” Williams said. “We want to go with younger players.”70 The highest-paid Mariner in team history wasn’t producing with only 10 homers and 26 RBIs. On July 16, he was signed by the Brewers after they lost 14 of 19 games and fell to last place in the AL East; they needed a strong bat to DH and back up first base. He was home again, playing for George Bamberger, who gave him his big chance. On his second day back, batting cleanup, he was the DH in the first game of a doubleheader. He played first base in game two and hit a home run. It was his first time in the field since the shoulder surgery. As in Seattle, he started hitting well and then struggled. After batting fourth for a month, he dropped in the order and played less. Hoping to hit 20 or more homers when he rejoined the Brewers, he finished with only six and 10 RBIs and batted only .179.

At age 35, Thomas’s career ended when the Brewers released him on October 16. He retired as the Brewers’ career home run leader with 208. Striking out 1,339 times in his 13-year career, he looked more like a twenty-first-century all-or-nothing hitter. He made Milwaukee baseball fun during his five-year peak when he hit more home runs than anyone and missed four consecutive titles by four homers.71 He was a free spirit who gave everything between the lines, never finding a wall he couldn’t run into which probably prematurely ended his career. He was a flake, a free spirit, and a folk hero in Milwaukee.

Thomas did have a life after baseball. His initial venture was a neighborhood bar on the south side of Milwaukee for several years in the mid-’80s with his best friend and fellow Brewer Pete Vuckovich named Stormin and Vukes. Going through a messy divorce in 1987, he made mistakes including two drunk-driving arrests with a 10-day jail sentence. Instead of serving the jail time, he left for his hometown, Charleston, South Carolina, where he owned a bar, Stormin Gorman’s, and golfed daily. He returned to Wisconsin in 1994 to serve the jail time and was hired by the Brewers, who wanted to help him get his life in order. He scouted and did personal appearances. In 1995, he moved back to Milwaukee with the Brewers opening Gorman’s Grill at County Stadium and then Gorman’s Corner when the team moved to Miller Park. He got involved in their community outreach and attended Brewers fantasy camps.72 He was inducted into both the South Carolina and Wisconsin Athletic Halls of Fame as well as the Brewers Wall of Fame. He married Susie Wiggins and as of 2019 the couple resided in the Milwaukee area.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to SABR member Bill Mortell of Maryland whose knowledge of Ancestry.com and research skills have proven invaluable in finding information on Gorman Thomas.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, the online archives via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 National Baseball Hall of Fame, Gorman Thomas File, 1974; Jerome Holtzman, “Thomas Is Still Indomitable.” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1985.

2 Hall of Fame file.

3 Mario Zino, “Test Pilot, Gorman Thomas Was the Franchise’s First Pick.” Brewers Game Day, Issue 22, 2013.

4 Hall of Fame file.

5 Hall of Fame file.

6 Zino.

7 Hall of Fame file.

8 Thomas signed his first professional contract with Bob Clements, Jack Sanford, and Bobby Mattick.

9 Other noted players selected before Thomas included first pick Jeff Burroughs, J.R. Richard, Alan Bannister, Terry McDermott, Don Stanhouse, and Don Gullett.

10 Zino.

11 Ibid.

12 “Class A Leagues,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1971: 45.

13 Larry Whiteside, “New Delivery in Parsons Message,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1973: 42.

14 Although a triple was his first hit, he had only 13 in the major leagues.

15 Slash line: batting average/on-base percentage/slugging average.

16 “A.A. Atoms,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1973: 38.

17 The left-field wall was only 233 feet from home plate, less than the 250-foot minimum. It was a one-year concession to return a franchise to Sacramento playing in a football stadium. The club was required to move the wall back after the season.

18 Thomas reported to camp with orange hair, a failed attempt at dyeing it blond. He was a free spirit and prankster always looking for ways to have fun while not appearing serious about the game.

19 Lou Chapman, “Thomas Removing Doubts as Brewer Bomber,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1975: 13.

20 Ibid.

21 On July 27 and 28 at Boston, Thomas became the third player to strike out in eight consecutive at-bats, following Rick Monday in 1970 and Wayne Twitchell in 1973. “Baseball,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1990: 14.

22 Lou Chapman, “‘Let’s Deal’ Moan Folding Brewers,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1976: 12.

23 “Brewers Obtain Giants’ Joshua.” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 3, 1976, Part 2, 1.

24 “Coast Toasties,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1977: 36.

25 Mike Gonring, “Thomas Set to Erase Brewers Doubts,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1978: 46.

26 Ibid.

27 Jamey Newberg, “Swapping Stories: The Gorman Thomas trades of 1977 and 1978.” Newberg Report, MLB.com/blogs, August 16, 2007.

28 Dalton was hired after what is known in Milwaukee as the Saturday night massacre, when team owner Bud Selig fired GM Baumann, anager Grammas and director of player development Al Widmar. Lou Chapman, “Brewers Purge Puts Dalton in Charge,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1977: 58.

29 Bob Nold, “Thomas Hitting Home Runs in Majors Now,” Akron Beacon Journal, June 21, 1978: 4.

30 Ibid.

31 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1978: 14.

32 Bill Schroeder, If These Walls Could Talk: Milwaukee Brewers (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2016), 76-77

33 Mike Gonring, “Brewers Reap RBI Harvest on Thomas’s Bat,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979: 39.

34 Anthony Cotton, “Gorman Is Always Stormin’,” Sports Illustrated, September 9, 1979: 90.

35 Ibid.

36 “Thomas Shares AL Whiff Mark,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1979: 28.

37 Ibid.

38 Cotton.

39 The Brewers drew 1.9 million fans, the largest Milwaukee attendance since the Braves had 1,971,101 in 1958, their second consecutive World Series season.

40 Don Kausler Jr., “Yount Leads Brewers’ HR Parade,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 2, 1980: Part 2, 1.

41 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1980: 6.

42 Joe Goddard, “They’re Doing the Hustle,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1980: 3.

43 “Bunts and Boots,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1981: 46.

44 Peter Gammons, “Goryl and Fregosi? Typical Fall Guys!,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1981: 16.

45 Joining Thomas Were Teammates Rollie Fingers and Ted Simmons.

46 “Wage Dispute Unresolved,” Milwaukee Journal, August 10, 1981: Part 2, 5.

47 “Quote, Unquote,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1981: 9.

48 The Milwaukee fans saw a familiar postseason foe, the New York Yankees, whom the previous County Stadium tenants, the Braves, had faced in the 1957 and 1958 World Series.

49 Although the Brewers were anxious to start the season, the April 6 home opener and the rest of the series were called off after an 8.7-inch snowstorm blanketed the ballpark. The team flew to Houston to work out for three days and then opened in Toronto on Friday.

50 Vic Feuerherd, “Rogers Fired, Kuehn at Helm,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 3, 1982: 1.

51 Tom Flaherty, “Crises Nothing New for Kuehn,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1982: 14.

52 Ibid.

53 Tom Flaherty, “Edwards Success Keyed to Patience,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1982: 26.

54 Vic Feuerherd, “Thomas Key Hit Pain to Angels,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 6, 1982: Part 2, 1.

55 Vic Feuerherd, “Kuehn Had No Doubt.” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 4, 1982: Part 2, 5.

56 ALS Game Five remains the best, most electric game this author ever attended along with his then 7-year-old son, Derek.

57 Vic Feuerherd, “Thomas, Oglivie Not 100%,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 12, 1982: Part 2, 1.

58 They would have record attendance on three consecutive days with 56,560 on Saturday and 56,562 on Sunday.

59 “In the A.L.: Right Makes Might,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1982: 28.

60 Dick Young, “Moffett — Players Deal Too Cozy,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1982: 7.

61 “Gorman Leaves ’Em Mourning,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1983: 16

62 Terry Pluto, “Brewer Fans Love Thomas,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 25, 1983: 1-D.

63 Manning remained with the Brewers, retiring after the 1987 season, one year after Thomas.

64 Bill Plaschke, “Thomas Accepts Shoulder Surgery,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1984: 20.

65 Ibid.

66 Thomas’s doctor eventually allowed light throwing during the season. He was happy to play again, but he would only DH for Seattle.

67 Bill Plaschke, “‘Gormbo’ Heats Up With Homer Binge,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1985: 22.

68 “A.L. West,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1986: 38.

69 “A.L. West,” The Sporting News, February 3, 1986: 40.

70 “Mariners’ Thomas Swept from Roster,” Boca Raton (Florida) News, June 26, 1986: 3D.

71 Thomas won the home-run titles in 1979 and 1982, missing the 1980 title by three homers and by one in 1981.

72 This author had the pleasure of talking smack daily with Stormin’ Gorman at the ’82 Brewer Players Fantasy camp in 2005.

Full Name

James Gorman Thomas

Born

December 12, 1950 at Charleston, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.