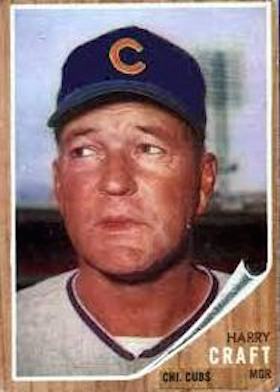

Harry Craft

He had a hard time hitting major-league pitching, but his stellar fielding helped the Cincinnati Reds win two consecutive National League pennants.

He had a hard time hitting major-league pitching, but his stellar fielding helped the Cincinnati Reds win two consecutive National League pennants.

There were several ups and downs in Harry Craft’s career. His catch of a fly ball for the final out of a 1938 game enabled a teammate to complete one of the most spectacular pitching achievements of all time. In a 1939 World Series game, he stood helplessly in center field and watched Yankee players score as his catcher lay prone at the plate. The lowest point of all came when one of his teammates became the first major-league player ever to commit suicide during the season. Craft was proud of being the first professional manager of a 17-year-old kid who became one of the greatest players of his generation.

Harry Francis Craft was born April 19, 1915, in Ellisville, Mississippi, a small town with an interesting history in the southeastern part of the Magnolia State. Ellisville was named for Powhatan Ellis, an early United States Senator, who claimed descent from Powhatan, the father of Pocahontas. The town is the county seat of Jones County, a center of pro-Union sentiment during the Civil War. The county attempted to secede from the Confederacy and establish the “Free and Sovereign State of Jones.” Volunteers fought several skirmishes against Confederate troops sent to crush the rebellion.

Harry did not linger long in Ellisville, growing up in various places in Mississippi and Texas. His parents, Mary Emily “Emmie” Morrison and Thomas Jefferson Craft, Jr., moved around a bit. According to his draft registration card, in 1918 Harry’s father was a timekeeper for a shipbuilding company in Moss Point, Mississippi. By 1920 his father was unable to work and Harry was living with his parents, his brother Tom, and two uncles in Jasper County, Mississippi, in a household headed by his unmarried aunt, Helen Morrison. Thomas Craft died in 1926, and Harry moved to West Texas to live with his uncle, Tom Morrison, who owned a grocery store in the town of Throckmorton, between Abilene and Wichita Falls. After graduating from Throckmorton High School, Harry returned to Mississippi, where he attended Mississippi College, a Baptist-affiliated institution in Clinton.

In 1935 the Cincinnati Reds organization signed Craft out of college and sent him to southwestern Pennsylvania to play for the Monessen Reds in the Class D Pennsylvania State Association. The next year they promoted him to Class C, where he played for the El Dorado Lions in the Cotton States League. Three more steps up the ladder came in 1937, starting with the Waterloo Reds in the Class A Western League, progressing through the Syracuse Chiefs of the Class AA International League, and reaching the pinnacle with a late-season call-up to the big club.

Harry Craft made his major-league debut at Crosley Field in the first game of a doubleheader on Sunday, September 19, 1937. It was an auspicious beginning to his big-league career. He went 3-for-6, with a triple, two singles, and two runs scored, as the Reds lost to the Boston Bees, 7-6. The 22-year-old center fielder was a 6-foot-1, 185-pounder, who batted and threw right-handed. Once in the starting lineup, he stayed there most of the time until World War II interrupted his career. He was given the nickname Wildfire, but it was seldom used.

Craft made his debut at a fortuitous time. The Reds were on their way up in the baseball world. Following their World Series win in 1919, the club had fallen upon bad times, becoming perennial dwellers in the second division. Tottering on the edge of bankruptcy in 1933, the historic franchise was rescued by entrepreneur Powel Crosley, Jr., who assumed majority ownership of the club. With the help of the innovative Larry MacPhail, the veteran Warren Giles, and other able front-office personnel, Crosley started the long process of restoring the club to its former glory. Progress was hard to see. From 1926 through 1937 the Reds dwelt in the second division every year, with five last-place finishes. The Reds were still a last-place team when Craft joined them in 1937, but they were ready to make their move.

In 1938 the Reds hired Deacon Bill McKechnie as their manager. An astute manager and, by all accounts, a wonderful human being, McKechnie had won a National League pennant and a World Series as skipper of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1925 and led the St. Louis Cardinals to the National League title in 1928. In his first season in the Queen City, McKechnie brought the Reds home in fourth place, their best finish since 1926. In 1939 and 1940 he guided them to back-to-back pennants and kept them in the first division for seven consecutive years.

Harry Craft made his biggest contribution to Cincinnati’s new-found success by his outfield play. Never an outstanding hitter, he earned his keep in the field. Fans, sportswriters, and teammates heaped praise upon his fielding, while expressing disappointment in his work at the plate. Baseball historian Lee Allen’s comments were typical: “When Craft took over the center-field job in 1938, he showed all sorts of promise. His fielding was the best that pasture had seen since Edd Roush departed, and it was felt that if only his stick work would improve he would surely reach stardom. Instead, Harry’s work at bat seemed to grow less and less impressive.”1

The stat sheets provide evidence of Craft’s fielding prowess. In both 1938 and 1939 he led National League outfielders in putouts. In 1939 he led in double plays by a center fielder; five times he was in the top five. Twice he was second in outfield assists and was third once in that category. Not only did he have sufficient speed to cover enough ground to run down fly balls or line drives, he also had the arm strength and accuracy to throw opponents out.

One of the highlights of Craft’s first season in the major leagues came on his catch of a routine fly ball at a most opportune time. Johnny Vander Meer had pitched a no-hitter on June 11. Four days later he was facing the Brooklyn Dodgers in the first night game in the history of Ebbets Field. Inning after inning the pitcher kept mowing down the Dodgers, keeping them hitless through the eighth. Excitement reigned supreme in Ebbets Field as fans sensed the possibility of a second consecutive no-hit game, something that had never been achieved in the long history of major-league baseball. Vander Meer retired the first batter in the ninth, then suffered a streak of wildness, walking three straight batters to fill the bases. He got the next batter to ground into a forceout and was one out away from accomplishing the unthinkable. Dodger shortstop Leo Durocher came to the plate and lifted a fly to short center field. Harry Craft came racing in, made the catch, and Johnny Vander Meer became Johnny “Double-No Hit” Vander Meer.

Craft’s second and third seasons in The Show saw the Reds win their first pennants in 20 years. In the 1939 World Series the Reds faced the New York Yankees. One of the strongest teams of all time, the Bronx Bombers had won their fourth straight American League pennant and were heavily favored to win their fourth consecutive World Series. They had swept the Chicago Cubs in the 1938 Fall Classic and expected to do the same to the Reds in 1939. The Yanks took the first three games by scores of 2-1, 4-0, and 7-3. The Reds put up a battle in Game Four, taking a 4-2 lead into the ninth inning, but the Yankees tied it up and sent the game into extra innings.

Frankie Crosetti led off the tenth frame for the Yankees by drawing a base on balls; Red Rolfe sacrificed him to second, Charlie Keller was safe on an error by shortstop Billy Myers. Joe DiMaggio then hit a ball to right field, scoring Crosetti to give the Yankees the lead. The ball got past the right fielder, Ival Goodman, and Keller tore around the bases, crashing into Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi at home plate. As Lombardi lay prostrate on the ground, DiMaggio rounded the bases and scored, bringing the final tally to 7-4. Cincinnati failed to score in the bottom of the frame, and the Yankees had their sweep.

Newspapers unfairly ridiculed Lombardi for his “snooze” or “swoon.” He was not napping. Keller had inadvertently kneed Lombardi’s groin. The catcher went down on his back, perhaps “writhing in pain,”2 or perhaps “unconscious.”3 At any rate, Lombardi was incapacitated and should be held blameless for the incident. Why were writers of the time so hard on Lombardi, who was a very likeable and highly respected man? Pitcher Bucky Walters offered an explanation: “It was a dull series and they had nothing else to write about so they picked on poor old Ernie.”4

It was no disgrace to lose to the powerful 1939 New York Yankees. However, competitive ballplayers never like to lose. In their frustration, players will sometimes lash out at teammates. The Reds lost the first game of the ’39 Series when Charlie Keller hit a long fly into right-center that fell between Craft and right fielder Ival Goodman for a triple. According to third baseman Bill Werber, Goodman should have caught the ball, but was bothered by the October shadows at Yankee Stadium and misplayed the fly.

After the game losing pitcher Paul Derringer screamed at Goodman, “That was the most gutless effort I’ve ever seen.”5 Goodman wasn’t going to take the insult and threw a right at Derringer’s jaw. Teammates quickly separated the two. Manager Bill McKechnie took charge, ordered the doors closed, and said not to let anyone in until this is straightened out. “If news of this gets out,” he said, “it is going to cost someone $1,000.”6 The combatants shook hands, and not a word about the incident appeared in the newspapers.

Although Werber was usually a gracious gentleman, he could be a sore loser. Immediately after the 1939 Series, he vented his displeasure. “We gave them two, and they won two,” he griped. “In the first game, they beat us, two to one on what they said was Charley Keller’s booming triple in the ninth. Booming triple, my ass. It was a high fly to right-center that neither of our outfielders [Harry Craft in center and Ival Goodman in right] called for. Why, our second baseman, Lonnie Frey, could’ve caught it. If any one of them had, it might have made a difference in the whole Series.”7

Later, of course, Werber was more understanding of the circumstances.

In 1940 the Reds defended their title, winning their second consecutive National League pennant. Craft didn’t contribute much at the plate, hitting only .244 for the season. However, he continued his excellent outfield play, leading the league in fielding percentage. Werber told a story about an unusually hot and humid day in Cincinnati that summer. Craft and Goodman showed up with large cabbage leaves and put them on top of the ice in the dugout water cooler. When it came time for the game to begin, they put the leaves under their caps and went into the outfield. Both had to leave the game because of nausea in the fourth or fifth inning. Werber didn’t know if the cabbage was responsible for the nausea, but he suspected it was.8

One tragic event occurred in the summer of 1940, shaking the club to its very foundation. In late July Lombardi suffered a badly sprained ankle. Backup catcher Willard Hershberger was pressed into service, catching every game, including doubleheaders in the heat of that very hot summer. Hershberger was worn out and blamed himself when the Reds lost three games in a row. On August 1, Cincinnati played a night game in New York against the Giants. Star pitcher Bucky Walters was on the mound for the Reds, taking a 4-1 lead into the bottom of the ninth. It appeared that the losing streak was about to end. However, Walters walked two men and gave up two home runs, with the Giants winning, 5-4.

Hershberger blamed himself for the loss. “I called for the wrong pitches,” he lamented. “If Lom had been in there, we wouldn’t have lost. I’ve let the team down.”9

The next day the Reds had a doubleheader in Boston. Hershberger did not show up at the ballpark. The club secretary had someone check the player’s room. It was found that Hershberger had taken off all his clothes except his shorts, spread newspapers on the floor, cut his aorta with a razor, leaned over the bathtub, and bled to death. The Reds were terribly shocked by the tragedy, but McKechnie rallied the troops and they went on to win the pennant. Craft was not hitting, so on August 23 the Reds purchased Jimmy Ripple from Brooklyn and installed him in centerfield, benching Craft, who would make only one appearance in the upcoming World Series.

In the American League the Yankees’ streak of four pennants in a row came to an end, and Cincinnati faced the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. It was a hard-fought Series between two evenly-matched teams. The Tigers won the first game, the Reds took the second, and so it went. Going into the final game of the Series, it was tied at three games each. As the Reds had won Game Six behind Walters, it was the Tigers’ turn to win Game Seven, but Derringer pitched a masterpiece, winning, 2-1, and giving Cincinnati its first World Championship since 1919.

The Reds were unable to repeat in 1941, and Craft had an unremarkable season. He got into only 37 games in 1942, as his big-league career was winding down. At the age of 27, the age at which most ballplayers are hitting their peak, he played his final major-league game on July 14, 1942 as the Reds lost to the Philadelphia Phillies, 2-1. Craft had two plate appearances in the game, and Rube Melton struck him out both times, dropping his season average to an abysmal .177. Two days later he was bundled with some cash considerations and traded to the New York Yankees for Eric Tipton.

Craft never played a game for the Bronx Bombers, who sent him to their farm club, the Kansas City Blues in the Class AA American Association. On May 26, 1943, Craft entered the United States Navy Pre-Flight School at Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He missed the entire 1944 and 1945 baseball seasons. Upon his discharge from the Navy on February 20, 1946, he rejoined the Kansas City Blues and played with them through 1948. Unable to hit major-league pitching, Craft attained a .308 batting average over his eight minor-league seasons.

In 1949 the Yankees sent Craft to Independence, Kansas, to manage their affiliate in the Class D Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri League. The Independence Yankees were quite a bunch. Led by a fun-loving 17-year-old boy from rural Oklahoma named Mickey Mantle, the players vented their youthful high spirits in a number of pranks. The average age of the crew was 19, and they sometimes acted like teenagers away from home for the first time. Sometimes they filled paper bags with water and dropped them from upstairs windows on the heads of innocent passers-by below. Worse, they occasionally filled fire pails with water and emptied them on whoever tried to climb the staircase. The fun that got them into the most trouble was melon-fighting. The young men would collect melons, cut them into missile-sized pieces, and throw them at one another. Occasionally a section of overripe fruit might hit an unsuspecting guest, causing hotel managers to protest their behavior to Harry Craft, who would then scorch their young ears with his appraisal of their behavior. But he wasn’t too hard on them, for they were winning the pennant and making Craft successful in his first managerial position.

Their success in Independence earned both Craft and his star player promotions to Joplin in the Class C Western Association in 1950. The Miners won the pennant that year, giving Craft two championships in his first two seasons as a skipper. Mantle led the league in hits with 199, in runs with 141, and in batting average at .383. The minor leagues couldn’t hold him and he was off to the majors in 1951. Craft earned a promotion also, but not to the big leagues. The Yankees sent him to Beaumont, their affiliate in the Class AA Texas League. After two seasons in Texas, Craft moved up again; this time it was to Kansas City in the Class AAA American Association.

In 1957 Craft made it back to the big leagues as a manager. He managed Kansas City from 1957 to 1959. In 1961 he joined the Chicago Cubs and their so-called College of Coaches. The ill-fated experiment replaced the manager’s position with a rotating series of head coaches. In 1962 Craft became manager of the Houston Colt .45s, remaining with the club until he was fired on September 19, 1964. In all he managed six seasons in the major leagues, and had a losing record every year. After leaving Houston he became field coordinator for the Baltimore Orioles, where his responsibilities included assisting in spring training, scouting, and working with young players during the regular season.10 He retired from baseball in 1991.

Along with his baseball activities Craft found time for some matrimonial ventures. He married Betty Clair Barry in 1938. They had a son, Thomas Harry Craft III, born in 1942. Harry and Betty divorced in 1947. His second spouse was Mayo Gay Oglesby Lennan, whom he married in Kansas City on January 18, 1950. They were divorced in 1952. His third trip down the aisle came in Miami, Oklahoma, on May 8, 1959, when he married Annelle “Nell” Moon. This union lasted the rest of his life and produced a daughter, Carole Anne, born in 1962. After his marriage to Nell, Craft built a home in Inverness, Florida, on Lake Tsala Apopka. In 1970 they moved to Conroe, Texas, in Montgomery County, and filled their home with baseball memorabilia.

Harry Francis Craft died in Conroe, Texas, on August 3, 1995, at the age of 81. An avid fisherman, he requested that his remains be cremated, with the ashes strewn on his favorite fishing hole at Lake Conroe.

Craft never made it into Cooperstown, but he has been inducted into four Halls of Fame: Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame, 1963; Mississippi College Hall of Fame, 1973; Mississippi Sports Hall of Fane, 1975; and Texas Baseball Hall of Fame, 1985.

Notes

1 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948, 277.

2 Talmage Boston, 1939: Baseball’s Pivotal Year, Fort Worth, Texas: The Summit Group, 1994, 83

3 Allen, op. cit., 275.

4 Bucky Walters, cited by Boston, op. cit.

5 Quoted by Bill Werber and C. Paul Rogers III, Memories of a Ballplayer, Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001, 45.

6 Ibid.

7 Werber quoted by Rich Wescott, Masters of the Diamond, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1994, 166-67.

8 Ibid., 188-89.

9 Ibid., 176-77.

10 Associated Press, November 6, 1964.

Full Name

Harry Francis Craft

Born

April 19, 1915 at Ellisville, MS (USA)

Died

August 3, 1995 at Conroe, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.