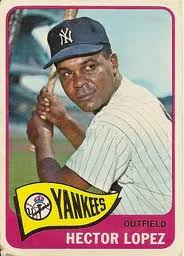

Hector Lopez

Hector Headley Lopez, the Panamanian-born third baseman for the Kansas City Athletics, saw his solid career shift to a better team when the A’s traded him to the New York Yankees on May 26, 1959. After more than four seasons in Kansas City as a regular infielder, mostly at third base, Lopez continued to play well, hitting .283 in 112 games for the third-place Yankees the rest of the ’59 season. A right-handed batter who hit to all fields and displayed good power, notably in the clutch, Lopez slugged a career-best 22 home runs in 1959, including 16 while playing for New York. But he also committed 31 errors, mostly at the hot corner. Despite his continued improvement, Hector picked up a misleading label with sportswriters: “good stick – weak glove.”

Hector Headley Lopez, the Panamanian-born third baseman for the Kansas City Athletics, saw his solid career shift to a better team when the A’s traded him to the New York Yankees on May 26, 1959. After more than four seasons in Kansas City as a regular infielder, mostly at third base, Lopez continued to play well, hitting .283 in 112 games for the third-place Yankees the rest of the ’59 season. A right-handed batter who hit to all fields and displayed good power, notably in the clutch, Lopez slugged a career-best 22 home runs in 1959, including 16 while playing for New York. But he also committed 31 errors, mostly at the hot corner. Despite his continued improvement, Hector picked up a misleading label with sportswriters: “good stick – weak glove.”

In 1960 manager Casey Stengel moved light-hitting Clete Boyer to third base and took advantage of Lopez’s versatility by using him as a utility player. At one time or another for Kansas City and New York, Lopez handled all four infield and all three outfield positions. For the Yankees he usually played left or right field. In 1960, for example, he played in 131 games, 106 in the outfield, five at second base, one at third base, and 25 games soley as a pinch-hitter (in some games he appeared in multiple capacities). Averaging .284 in 408 at-bats in 1960 (down from 541 at-bats in 1959), “Hector the Hit Collector,” as writer George Vecsey dubbed him, contributed 14 doubles, six triples, and nine home runs.

In his 12 big-league seasons for Kansas City and New York, Lopez averaged .269, collecting 1,251 hits, including 193 doubles, 37 triples, and 136 homers. When the Yankees won American League pennants from 1960 to 1964, Lopez played in five straight fall classics. Batting .286 in the post-season, Lopez twice played for World Series champions, in 1961 and 1962.

When the Bronx Bombers defeated the Cincinnati Reds in five games in the 1961 World Series, Lopez, who had batted only .222 during the regular season, hit .333 in four games. He produced all seven of his World Series RBIs in 1961, driving home five runs with a home run and a triple in the decisive fifth game, a 13-5 Yankee romp.

Considering that he grew up in Latin America at a time when black players could not make it to the major leagues, Lopez enjoyed a very successful professional career. Born on July 8, 1929, in Col?n, Panama, he grew up loving beisbol. He liked watching his father, Manuel, pitch for local teams, and he inherited his father’s passion for the game.

In a 1963 interview with New York sportswriter Hugh Bradley, Lopez recalled how kids in Col?n would play pickup games using a broom handle for a bat and a ball made of a taped piece of rubber. “My eyes and reactions must have been good,” he said, “because bigger guys tabbed me as a home-run hitter and invited me to play on their teams.”

Lopez continued, “Ever since I can remember I wanted to be a ballplayer. Things didn’t seem bright, though. Panama is crazy about baseball but most of those few who had a chance in the majors were pitchers. I was a skinny little infielder.”

Lopez graduated in 1950 from Col?n’s English-speaking school, Rainbow City High. During those years he specialized in auto mechanics, played baseball, and worked in a bowling alley on the local American military base. After high school he played two years in Panama’s amateur provincial league. Leo Kellman, who managed a team in the Panama Professional League, saw Lopez, a good-hitting shortstop, and signed him for the winter season of 1950-1951.

Lenny Pecou, a part-time scout and career minor leaguer who played outfield in 1950 for St. Hyacinthe, Quebec, in the Class C Provincial League, saw Lopez playing winter ball and recommended him to St. Hyacinthe. The independent club signed the 21-year-old Panamanian, and he played the 1951 season for the fifth-place Saints, hitting .297.

In 1952 Lopez returned to the Provincial League, down from eight to six teams, and hit .329. Contributing six home runs, 75 RBIs, and a league-leading 115 runs scored, he helped St. Hyacinthe—now affiliated with the Philadelphia Athletics—finish in first place and also capture the playoff championship in seven games over third-place St. Jean.

Lopez ended up with the Athletics organization in 1953 because scout Joe McDonald saw him play. Philadelphia signed Hector and sent him to Williamsport of the Class A Eastern League. The A’s finished sixth, but he hit a solid .270 with eight homers and 51 RBIs.

“That was a pretty tough league,” Lopez remembered in 2003. “They had guys like Rocky Colavito and Herb Score and others who made the majors. I was playing shortstop at that time, and I came up to the A’s as a shortstop. When I got to Kansas City, they moved me to third base, and to second base, and to center field, and all over.”

Assigned to Ottawa of the Triple-A International League in 1954, Lopez continued to play well, batting .316 with eight home runs and 53 RBIs. In 1955 he went to spring training with the Athletics, after the franchise had been shifted to Kansas City, but was sent to Triple-A Columbus, also in the International League, to learn how to play second base. After he batted .321 in the first month of the season, the Athletics called him up on May 12.

Lopez recalled, “I played a lot of second base for Kansas City in 1955, but they moved me around. Kansas City was trying to get good ballplayers at that time. Every time they were short somewhere, they tried to use me there. They just kept moving me around. It’s hard to learn a position if you have to keep moving.”

Lopez was a candidate for Rookie of the Year honors, but Cleveland’s southpaw Herb Score won the award with his 16-10 season. Still, Hector enjoyed a good year, averaging .290 with 15 doubles, two triples, 15 homers, and 68 RBIs.

Lopez’s play at third helped stabilize KC’s infield. Vic Power, a flashy Puerto Rican who loved making one-handed sweeping catches of thrown balls, played first base. Good-hitting Jim Finigan played second base and sometimes at third. Not a strong fielder, Finigan altered his swing. The change didn’t work, and he batted .255, after hitting .302 as a rookie in 1954. Veteran shortstop Joe DeMaestri, who hit .249 in 1955, rounded out the infield.

In 1955 Lopez played 128 games, 93 at third and 36 at second (with one game at both), but he committed 23 errors at third (he made 29 total errors), a figure that topped AL third basemen.

“I surprised myself in 1955,” Lopez later observed. “I had a lot of home runs too, and I wasn’t a home-run hitter. I was more of a fielder in those days than a hitter. We had good players, guys like Vic Power at first, Suitcase Simpson and Gus Zernial and Enos Slaughter in the outfield, Joe DeMaestri at short, Jim Finigan at second and third, Joe Astroth at catcher, and Alex Kellner, a pitcher, Bob Shantz, another good pitcher, and Arnie Portocarrero, a pitcher.”

Lopez lived with Harry “Suitcase” Simpson, a 6-foot-1 outfielder from Atlanta who picked up the nickname during his Negro League days in the late 1940s. Simpson wore size 13 shoes. One writer said his feet were big as a suitcase, like a character in the “Toonerville Folks” comics, and the tag stuck. Even though there were places where minorities couldn’t go, restaurants where they couldn’t eat, or things they couldn’t do, Lopez recalled, “It wasn’t too bad at Kansas City. I got along with everyone, and they treated me well. Suitcase Simpson and me rented an apartment in a family home. We had the whole upstairs. They treated me all right in Kansas City. I can’t complain.”

Playing under manager Lou Boudreau, a former shortstop later elected to the Hall of Fame, Kansas City finished sixth in 1955 with a 63-91 record. During Lopez’s tenure, the Athletics remained a second-division club, finishing last in 1956, seventh in 1957, and seventh in 1958.

In 1956 Lopez enjoyed a good season at the plate, hitting .273 with 27 doubles, three triples, 18 homers, and 69 RBIs. He played 121 of his 151 games at the hot corner, where he led AL third basemen with 26 errors. Still, Boudreau continued to move the former shortstop around, using him in the outfield 20 times as well as at second base (8 games) and shortstop (4 games).

Lopez handled the moves with grace. A good fielder, he had to keep adjusting to another position. When his numbers were compared to those of others who played the same position, Hector looked good. He had a knack, however, of booting a play at a place like Yankee Stadium, where the error drew more publicity. On the other hand, Gene Woodling, the fine Yankee outfielder, mishandled a ninth-inning fly ball against the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1950 World Series, but nobody wrote that he had “bad hands.”

Never outspoken, Lopez was a good player and a good teammate everywhere he played. Fans like to see clutch hitters, especially those who can hit home runs, and hard-hitting Hector, with his brown eyes, black hair, and pleasant personality, became a fan favorite in Kansas City.

In May 1957, during a season in which he hit a career-best .294 with 19 doubles, four triples, and 11 home runs, Lopez fell into a slump. Boudreau, who was later replaced by Harry Craft, benched the Panamanian for a few games. On June 15, back in the lineup at home against the Yankees, Lopez began a 22-game hitting streak that lasted until the Red Sox shut him down on July 16. Averaging .256 before the streak, Hector went 36-for-83, an impressive .434 mark.

“I had four good years with Kansas City,” Lopez recalled in 2003. “You get better when you can play every day. Either you get better, or you get worse. I kept getting better, and I got help from some good guys. Veterans like Suitcase Simpson, they knew the game. They helped me. When I was at St. Hyacinthe in 1951, I roomed with Connie Johnson, who later pitched in the majors. Connie taught me a lot about hitting good pitching. In 1952 I roomed with Joe Taylor, who also made it to the majors, and Al Pinkston, who was a good minor leaguer. These guys would talk, and I would just listen and learn. Wherever I went, the veterans would talk, and I would listen.”

Reflecting on Kansas City being a second-division team in the 1950s, Lopez commented, “The Athletics didn’t get too high in the standings. They traded most of their good ballplayers, and most went to the Yankees. Kansas City was trying to build a ballclub, and they could get three or four players from the Yankees for one or two players. There wasn’t any draft at that time. Everybody wanted to play with the Yankees, so the Yankees signed a lot of ballplayers.”

Standing 5-feet-11 and weighing 180 pounds by 1958, Lopez enjoyed his fourth solid season with the Athletics, hitting .261 with 28 doubles, four triples, and 17 home runs –his fourth straight season of double-digit homers. Of his 151 games, Hector played 96 at second base.

The right-handed batter enjoyed one of his best days as a big leaguer on June 26, 1958. Playing at KC’s Municipal Stadium against the Washington Senators, Lopez pounded three of his 17 home runs off three different Washington right-handers, leading the A’s to an 8-6 victory. Batting against Hal Griggs in the fourth inning, Lopez hit a solo blast. Against Tex Clevenger in the eighth, Hector unloaded a two-run shot. Finally, hitting against Vito Valentinetti in the 12th, he won the game with another two-run homer.

Lopez began the 1959 season playing second base. At the time of his trade, he was hitting .281. The Athletics swapped Lopez and right-handed pitcher Ralph Terry to New York for right-handers Johnny Kucks and Tom Sturdivant and infielder Jerry Lumpe. Considering the later heroics of Lopez and Terry, the Yankees got the best of that deal.

Lopez got off to a good start. On June 9 he lifted the Yankees to a 13-inning, 9-8 victory over the Athletics with a line single to right, driving in Yogi Berra with the game-winning run. In the 4 hour and 10-minute contest, Lopez went 3-for-5 with one walk, and he saved the game. In the ninth he tripled and a few minutes later scored to tie the contest when outfielder Whitey Herzog muffed Gil McDougald’s short fly to right for a two-base error.

When the game ended, Lopez was hitting .307 for the year. In his first 12 games for the Yankees, he had gone 17-for-44, collecting 13 of his 69 RBIs for New York. Actually, against the A’s in the 13th inning, he failed to bunt twice before lining what could have been a double to right field. The ball bounced into the stands, and when Lopez rounded first and saw the game was over, he trotted to the dugout. The game-winner, which came off a Tom Sturdivant knuckleball, contributed to his growing reputation as a good two-strike hitter.

Lopez finished the season averaging .283, and hit 26 doubles and five triples as well as career highs with 22 homers and 93 RBIs. In 147 games, he played 76 at third base, 35 in the outfield, and 33 at second base. He committed 31 errors, but as Stengel said about the extra-inning win over Kansas City, Lopez’s clutch hitting and versatility outweighed any fielding mistakes.

Lopez maintained that he was a better fielder than sportswriters claimed. “Most of the managers I ever had kept shifting me around from one position to another,” he told Til Ferdenzi in 1963. “I was young then and I think it affected me.”

In 1960 the Panamanian contributed to the Yankees’ pennant-winning team, especially with his good bat. In a story dated May 11, 1960, “The Lonely World of Hector Lopez,” Stan Isaacs of Newsday detailed how Hector left the two-family home, where his mother also lived, in Brooklyn by 10 o’clock in the morning and made an hour-long subway ride to Yankee Stadium in order to be ready for batting practice at 11:30.

After an afternoon game, Lopez, a major leaguer who was virtually anonymous in private life, rode the subway home, usually arriving after 7:30. He spent most evenings with his mother and lived a quiet life away from the ballpark. In his spare time he was an excellent carpenter and mechanic. His lifestyle changed somewhat when he married Claudette Joyce Brown, his longtime sweetheart from Col?n, in Panama on November 30, 1960.

“One difference in playing in Kansas City and New York was that Kansas City wasn’t a big city, and everyone knows you,” Lopez said in 2003. “You walk around, and they all know you. In New York most people don’t know you. I lived in Brooklyn, and I’d catch a train every day. Finally, I got a car, and I’d drive to the Stadium.”

Before his wedding, Lopez played in the 1960 World Series, which the Yankees lost when Bill Mazeroski, the Pittsburgh Pirates second baseman, slugged a walkoff homer in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Seven. Playing in his first Series, Lopez got into three games. At Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field in Game One, he started in left field and singled in five trips. Lopez returned to the bench in Game Two, and didn’t emerge until Game Five, when he had a pinch-hit single. Lopez sat out Game Six, then got another pinch-hit single in Game Seven. Although he proved he could hit in October, averaging .429 with a 3-for-7 performance, he never got a real chance to contribute.

The Yankees came back in 1961 with another strong ballclub, and their pennant-winning season was highlighted by the home-run race between Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. The Bronx Bombers, living up to their nickname, capped the season by defeating the Cincinnati Reds in five games in the World Series. Lopez, however, played less during the regular season. In 93 games and 243 at-bats, he hit .222 with three home runs and 22 RBIs. Yogi Berra, who caught 15 games in 1961, played mostly left field, while the switch-hitting Mantle covered center and Roger Maris, a left-handed slugger, anchored right field. Lopez, who batted right-handed, platooned with left-handed batter Berra.

In the World Series, Lopez went 0-for-2 in Game One, then pinch-hit for Ralph Terry in the seventh inning of Game Two and drew a walk. He was on the bench for Game Three, but in Game Four he took over in the fourth inning for Mickey Mantle, who left the game with a hip injury. Lopez helped the cause with a two-run single in the seventh inning. New York won, 7-0, and went up three games to one. Game Five turned into no contest in a hurry. Joey Jay started and lasted two-thirds of an inning, and the Reds used seven more pitchers before the Yankees won, 13-5. Lopez tripled in a run in the first inning. In the fourth he hammered a three-run homer, and he brought home a fifth run with a bunt in the sixth.

“I had a pretty good World Series in 1961,” Lopez reflected in 2003, “I only got up to bat nine times but I got three hits and seven RBIs. I had to do something, because I had such a lousy season in 1961.” Asked why he didn’t play as much in 1961, Lopez replied, “With all those guys hitting home runs, they didn’t need me! Maris, and Mantle, and Johnny Blanchard, and Elston Howard, and Bill Skowron, and Yogi, those guys were hitting home runs all over the place. Six guys hit 20 or more home runs. … But not only did those Yankee teams hit well, but they were good defensive ballclubs. People never gave us enough credit for being a good defensive club.”

In 1962 Lopez bounced back with a solid season. Playing in 106 games, 84 of those in the outfield, he batted .275 with six home runs and 48 RBIs. Before long his solid performances won him a new nickname, according to sportswriter Hugh Bradley. In “The New Lopez: Good Hit – Good Field,” dated September 22, 1963, Bradley wrote that in 1962 the Yankees won 96 games and Lopez drove in the winning run seven times and scored the winning run ten times. So far in 1963, he had batted in the game-winner six times. Bradley observed that patience and practice made Lopez a better fielder at several positions. In 1962 he failed to catch only two balls in 182 chances in the outfield, and he had not missed a single play so far in 1963. He also threw out eight runners in 1963, a stat that compared favorably to great performers like Detroit’s Al Kaline.

In the 1962 World Series, when New York outlasted the San Francisco Giants in seven games, Lopez saw limited action, grounding out and flying out in two pinch-hitting appearances.

In 1963 the Yankees won their fourth straight pennant, and Lopez averaged .249 with 14 homers and 52 RBIs in 130 games. Hector, who loved to hit in Tiger Stadium, got off to a slow start, but had a big series there in June. On Friday the 7th he homered off lefty Hank Aguirre, but the Tigers prevailed, 8-4. On Saturday Lopez hit another solo home run, this time off southpaw Don Mossi, but the Tigers won again, 8-4. On Sunday he hit his third straight solo shot, a blast off Tom Sturdivant that helped the Yankees to a 6-2 win.

In Game One of the 1963 World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Lopez pinch-hit for Whitey Ford with the bases loaded in the fifth inning. But LA ace southpaw Sandy Koufax made Lopez his 11th strikeout victim, and the Dodgers went on to win, 5-0. In Game Two the Panamanian hit two doubles off lefty Johnny Podres. But Podres prevailed, 4-1.

Lopez didn’t play in Game Three, a 1-0 complete-game victory hurled by Dodgers’ star right-hander Don Drysdale. LA swept the Series by winning Game Four, 2-1, behind a route-going performance by Koufax. Lopez played in place of the injured Roger Maris (who ran into an outfield railing in Game Two, hurting his knee and elbow), and went 0-for-4.

By then Hector and his family had moved from Brooklyn to Long Island. After he married Claudette in 1960, the couple lived in the house on Hopkinson Avenue in Brooklyn that he had purchased for his mother and himself. “I was disappointed,” Claudette said in 1964.”All the houses were crowded next to each other. It wasn’t very clean or pretty. I didn’t like it in Brooklyn.” A couple of years later, they moved to a ranch house in West Hempstead, Long Island, on a quiet street where, Newsday’s Stan Isaacs wrote, “there are people with white skin and brown skin and where people in the supermarket come up to him and say, ‘Are you Hector Lopez?’ ”

Overall, Lopez played in five World Series. The Yankees won two of the five, and Hector averaged .286 in the post-season. But in 1964, when the Yankees – now managed by Yogi Berra – fell to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games, Lopez played in only three games, subbing once in right field and going 0-for-2 as a pinch-hitter.

The once-dominant Yankees won the 1964 pennant by one game over the Chicago White Sox. Lopez, who hit .260 in 127 games, enjoyed his last season of double-digit homers, hitting 10 round-trippers and producing 34 RBIs. The good hitter from Panama produced similar numbers in 1965, averaging .261 in 111 games with seven homers and 39 RBIs. But in 1966, his final major-league season, he played in only 54 games, batted 117 times, and hit .214. He was released by the Yankees after the season.

After being released Lopez played two seasons in the minors. He batted .295 with 13 homers for Hawaii of the Pacific Coast League in 1967, and he hit .258 with 13 round-trippers for Buffalo of the International League in 1968. Afterward, he received a new opportunity. Hector became the first black manager of a Triple-A club, piloting Buffalo to a seventh-place finish in 1969.

Lopez left baseball and spent 20 years working as a recreation director for the town of Hempstead. (West Hempstead, where he and Claudette lived, is part of Hempstead.) Later, he scouted for the Giants and also the Yankees, and he coached in New York’s minor-league system. Lopez passed away due to complications of lung cancer on September 29, 2022 at 93 years old.

Hector Lopez was proud to say that baseball and the Yankees had been good to him. “The game stays with you like your first romance,” he said, smiling. Once in a while the Panamanian hero used to look at his old Yankee uniform and think, I used to play for the greatest team in the world. No one can ever take that away from me.

Last revised: October 4, 2022 (zp)

Sources

Interview with Hector Lopez, June 18, 2003.

Hector Lopez on Baseball-Reference.com.

Clippings from the Hector Lopez File in the Library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York, including:

Hugh Bradley, “The New Lopez: Good Hit – Good Field,” New York Journal American, September 22, 1963.

Victor Debs, Jr., “That Was Part of Baseball Then” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Co., 2002).

Til Ferdenzi, “Spouse Too Good at Cooking – Lopez Had to Shed 14 Pounds,” New York Journal-American, March 15, 1961.

Dom Forker, Sweet Seasons: Recollections of the 1955-64 New York Yankees (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Co., 1990), 82-87.

Stan Isaacs, “Hector is Enjoying the Clean, Quiet Life,” Newsday, January 23, 1964.

Stan Isaacs, “The Lonely World of Hector Lopez,” Newsday, May 11, 1960.

Steve Jacobson, “Hector Lopez: From First to Jobless,” Newsday, June 9, 1970.

Irene Janowicz, “Woman in the Family: Claudette Lopez,” New York Mirror, September 29, 1963.

Fluffy Saccucci, “Hector Lopez: Integral Part of Big Pinstripe Machine,” Sports Collectors Digest, November 9, 1990, 250-251.

Randy Schultz, “Where Are They Now …? Bill Stafford and Hector Lopez,” Baseball Digest, June 1991, 67-68.

George Vecsey, “Hector Never Forgot How to Swing,” Newsday, July 9, 1962.

Full Name

Hector Headley Lopez Swainson

Born

July 8, 1929 at Colon, Colon (Panama)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.