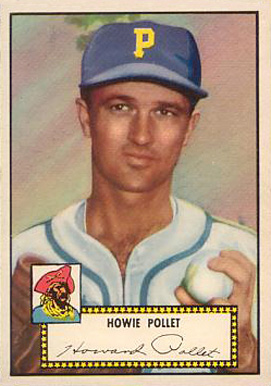

Howie Pollet

Left-hander Howie Pollet was a pitching prodigy, but arm injuries stunted his career. Howard Joseph Pollet was born in New Orleans on June 26, 1921 to Elodie (Wilson) and Joseph King Pollet, a policeman. The family name is French, but they pronounced it “pol-LET” rather than “Poh-LAY.” Growing up in New Orleans, Howard’s next-door neighbor was Mel Parnell, who became a left-handed pitching star for the Boston Red Sox.

Left-hander Howie Pollet was a pitching prodigy, but arm injuries stunted his career. Howard Joseph Pollet was born in New Orleans on June 26, 1921 to Elodie (Wilson) and Joseph King Pollet, a policeman. The family name is French, but they pronounced it “pol-LET” rather than “Poh-LAY.” Growing up in New Orleans, Howard’s next-door neighbor was Mel Parnell, who became a left-handed pitching star for the Boston Red Sox.

King Pollet died when Howard was 15, leaving his widow with two younger sons, Wilson and Lloyd, and a daughter, Shirley. Howard worked in a gas station to help support the family. He also pitched for Fortier High School and American Legion Post 197. His Legion junior team played in the national championship game in 1937, but lost to a team from East Lynn, Massachusetts.

Pollet’s boss at the gas station, Texaco executive Hugh McConaughey, recommended him to a friend in the oil business, Eddie Dyer, a former big-league pitcher also born in Louisiana and a longtime manager in the Cardinals’ farm system. Dyer was named Houston’s manager for the 1939 season and signed the teenager for a $3,500 bonus, beating out a half-dozen other clubs. Dyer became Pollet’s mentor and lifelong business partner. Pollet later said he had used part of his baseball bonus to buy the Harvard Classics book collection.

The 17-year-old joined the Houston Buffaloes, a Cardinals farm club in the Class A Texas League, in 1939, but was soon sent down to New Iberia, Louisiana, in the Class C Evangeline League. He pitched a no-hitter in August and followed that with a one-hitter in his next start. He struck out 212 batters in 163 innings, a phenomenal accomplishment in that era. (No major-league starter struck out one batter per inning until 26 years later.) He was deemed ready for the fast Texas League in 1940.

He was ready. Pollet won his first 12 decisions for Houston, celebrating his 19th birthday during the streak. He posted a 21-7 record with a 2.88 ERA. He lost one game to Dizzy Dean, who was trying to come back from arm trouble with Tulsa.

Despite that strong showing, Pollet returned to Houston in 1941. The Cardinals had the majors’ largest farm system and usually required their prospects to serve a long apprenticeship. He opened the season with three straight shutouts, the middle one a no-hitter against Shreveport. In August he won his 20th game, with a league-record 1.16 ERA. Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey watched that 20th win and broke his rule against calling up players in mid-season, because Houston was 24 games in front of its nearest rival on the way to a third straight pennant.

The Cardinals were locked in a tight pennant race with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Manager Billy Southworth immediately put Pollet into the rotation. In his first start he was nursing a 3-2 lead over the Boston Braves when he let the potential tying and winning runs reach base in the ninth. Southworth came out to relieve him, but the rookie protested, “Hell, I’m not in a spot, Mr. Southworth. I like spots like this.” He stayed in the game and won.

Pollet started eight times down the stretch, winning five, losing two and posting a 1.93 ERA. Sporting News publisher J.G. Taylor Spink dubbed him “the eleventh-hour sensation of this red-hot N.L. race.” Despite his late-season heroics and those of 20-year-old outfielder Stan Musial, who batted .426 in 12 games St. Louis finished 2 ½ games behind the Dodgers.

Rickey characteristically had plenty to say about the rookie: “He has inherent intellect. He was born with it and it shows in his pitching. What I mean is that he knows how to pitch and can put the ball just about where it should be pitched…No, Howard hasn’t the greatest fastball, but it’s a good one. It’s the variations of his speed and curves that count. He uses three speeds on his fast one and his curve comes up at different paces. The sameness of his delivery also is a fine asset. He has a technique all his own.”

Dick McCann of The Sporting News described the 20-year-old as “a soft-spoken, mild-mannered, honestly modest and quite model young man.” Shortstop Marty Marion, who roomed with Pollet for a time, remembered him as “a good Catholic boy…the calmest person I ever saw.”

After the season Pollet married 18-year-old Virginia Clark, a Houston girl he had met at a skating rink. Described as “a vivacious blonde” known as Ginger, she was studying piano at Loyola University in New Orleans. Howard (the name he preferred over “Howie”) spent the off-season working as a department-store detective in New Orleans.

Pollet developed a sore arm during 1942 spring training and was in and out of the starting rotation in the first half of the season. He didn’t start a game for seven weeks in July and August, but by mid-September was taking his regular turn. He pitched 27 times, only 13 of them starts, and registered an excellent 2.88 ERA and a 7-5 record.

The 1942 Cardinals won 106 games, but barely edged out Brooklyn in a classic pennant race. Another rookie, Johnny Beazley, joined veteran Mort Cooper as the aces of the pitching staff. In the World Series against the Yankees, Pollet relieved in the sixth inning of Game Four with the score tied and threw one pitch to retire the side. He was replaced by a pinch-hitter as the Cardinals staged a winning rally in the top of the seventh.

Pollet was the pitcher of record when his club took the lead, but the three official scorers awarded the win to Max Lanier, who held the Yankees scoreless over the final three innings. The Cardinals won the Series in five games, and each player took home a full share of $6,192.53, much more than Pollet’s annual salary.

World War II was under way and draft calls were claiming more and more ballplayers. Pollet went to work in a Houston defense plant in the off-season. When his draft board summoned him for a physical, he appealed for a deferment from military service because he was supporting his widowed mother and sister. (Being married didn’t matter under the draft rules at the time unless a man had a child born before Pearl Harbor.)

Pollet’s 1943 season showed every sign of living up to his promise. In July he had an 8-4 record with five shutouts. He had pitched three straight shutouts and 28 consecutive scoreless innings. He was chosen for the all-star team, but his draft board had classified him 1-A, available for immediate induction. On the day the All-Star Game was played, he enlisted in the Army Air Force. At the end of the season he was named the league’s ERA champion at 1.75. (Ten complete games were required to qualify for the championship; Pollet completed 12 in his half-season.)

Pollet’s 1943 season showed every sign of living up to his promise. In July he had an 8-4 record with five shutouts. He had pitched three straight shutouts and 28 consecutive scoreless innings. He was chosen for the all-star team, but his draft board had classified him 1-A, available for immediate induction. On the day the All-Star Game was played, he enlisted in the Army Air Force. At the end of the season he was named the league’s ERA champion at 1.75. (Ten complete games were required to qualify for the championship; Pollet completed 12 in his half-season.)

His military training took him to Miami Beach, Santa Ana, California, and Las Vegas, but he washed out of advanced gunnery school and never received a commission. In 1944 Private Pollet won 11 of 13 games for the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center team. His Cardinal teammate, Sergeant Enos Slaughter, was San Antonio’s star with a .414 average. Pollet went to the Pacific with military all-star teams in 1945 and continued to play exhibitions for the troops after the war ended. There is no mention in contemporary accounts of any combat service before he was discharged in November 1945.

Eddie Dyer had been named the Cardinals’ manager for 1946. Pollet had settled in Houston, his wife’s hometown as well as Dyer’s. The men were so close that Pollet had given Dyer his power of attorney while he was in military service. When he rejoined the Cardinals in spring training, teammates called him “Eddie’s boy.”

He was Eddie’s main man on the mound. In his first start he tacked seven more scoreless innings onto the 28-inning streak he had left behind when he went into the army three years earlier.

The Cardinals had a turbulent season. St. Louis had 10 pitchers of prime age returning from military service, but two of them, Howard Krist and Johnny Grodzicki, never recovered from their war wounds. Lefthander Ernie White, a 17-game winner in 1941, had fought through a freezing winter in the Battle of the Bulge and come home with a dead arm. None of those three ever won another big-league game. Johnny Beazley, the rookie sensation of 1942, had ruined his arm pitching for an army team in an exhibition against the Cardinals; his career was effectively over. Another prewar prospect, Hank Nowak, had been killed in action.

Two other pitchers, Max Lanier and Fred Martin, and second baseman Lou Klein defected to the Mexican League, which was tempting big-league players with fat salary offers. The Cardinals survived a scare when their superstar, Stan Musial, turned down a reported $50,000 signing bonus from the Mexicans, nearly four times his big-league salary.

After Lanier and Martin jumped the team, rookie manager Dyer said, “I felt like our pennant chances had been shot out from under us.” As Dyer recalled it, Pollet came to his hotel room and said, “‘Skipper, we’re all going to have to carry a little extra load. I’ll do my part. Give me a day’s rest after I start a game and I can relieve if you need me. Then another day of rest and I can start again’…Howie wasn’t a robust fellow, but his heart was stout and I’ll never forget it.”

Pollet’s friend Dyer took him up on that offer, and may have ruined his career. Pollet started 32 games, relieved in eight more and pitched a league-high 266 innings. His 2.10 ERA led the league as he finished 21-10. In August he was rushed into a game in relief without a proper warmup and strained muscles behind his shoulder, but he didn’t miss a start.

Two teams built by Branch Rickey, the Cardinals and Dodgers, finished tied for the National League lead. Both clubs had a chance to win the pennant on the final day, but both lost.

Pollet started the first playoff game in major league history in a best-of-three series. With just two days’ rest, he beat Brooklyn 4-2. In game two, fifteen-game winner Murry Dickson and his roommate Harry Brecheen put the Dodgers away to send St. Louis to the World Series for the fourth time in five years.

Pollet opened the Series against the Boston Red Sox on four days’ rest. He took a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning, but gave up the tying run with two out. Dyer sent him back to the mound in the tenth. Red Sox first baseman Rudy York had been embarrassed in his first three at-bats, but he told his teammates, “He’s gonna throw me a changeup one time, and when he does, I’m gonna hit it.” Pollet did and York did. His homer gave Boston a 3-2 victory.

During the game, it was reported, Pollet was digging his fingernails into his palm to fight the pain in his shoulder. He said he lay awake all night afterward, hurting. The Series was tied at two games apiece when he started Game Five. Three of the first four Red Sox batters got base hits and Pollet was relieved after throwing only 10 pitches. The Cardinals won the Series in seven games on Enos Slaughter’s fabled “mad dash” from first to home with the winning run.

Pollet finished fourth behind Musial in the National League most valuable player voting, but his future was in doubt at age 25. At a dinner in Houston after the Series, Dyer said, “There was a lot of kidding among the Cardinals about Pollet being ‘Eddie Dyer’s boy.’ Well, that suits me and I think it suits Howard, for Pollet is the type of man I’d like to have as a son or as a brother.”

Doctors treated Pollet’s shoulder during the off-season and Dyer reported he was recovering. But he lost his first three starts in 1947 and uncharacteristically walked eight batters in his first victory. Later he said, “Every pitch hurt. I began to pitch with a half motion, using my elbow instead of my back…and I began to feel a lump in my elbow. It frightened me. I was afraid I was through.” He started 24 games, winning nine and losing 11, and his ERA more than doubled to 4.34. After the season surgeons removed a bone spur from his elbow.

By this time Pollet had gone to work for Dyer’s Houston insurance agency and was taking insurance courses at the University of Houston in the off-season. Another member of the 1946 championship team, utility infielder Joffre Cross, also began a long career with the firm. Cardinal pitcher George Munger later worked for Dyer in the winters.

A 1948 spring training headline in The Sporting News asked, “Will Pollet and Musial Regain ’46 Form?” Stan the Man had suffered from appendicitis and had batted “only” .312, 53 points below his MVP performance of 1946.

Musial rebounded with the best season of his career, leading the league in practically every batting category and falling just one home run short of the triple crown. Pollet’s comeback attempt was not nearly as successful. He won his first four decisions, but was dropped from the rotation for nearly three weeks in July. Although he finished with a 13-8 record, his 4.54 ERA was 10 percent worse than the league average.

The 1949 season started no better. He was battered for 11 runs in his first six innings and was sent to bullpen. Dyer, who had been sticking up for him, now said, “You’ve started your last game until you throw the damn ball hard.” He waited two-and-a-half weeks for his next start, and soon began to look like the 1946-model Pollet. In one stretch he won four straight games and allowed just three runs in 35 innings.

“I think I was too cautious about my arm last year,” he told reporters. “I didn’t dare try to break off my sharp curve until July. Now I throw hard and give it the full snap of my wrist without thinking. Most important though is that I have my control.”

Back in top form, Pollet appeared in his only All-Star Game in July, but the American Leaguers torched him for three runs in his only inning. The Cardinals were in first place from August 17 until the last week of the season, when they lost four in a row and finished one game behind the Dodgers. Pollet apparently ran out of gas in September; he didn’t start for twelve days before won his twentieth in the season’s final game. He finished 20-9 with a league-leading five shutouts and a 2.77 ERA, third-best in the league. The Sporting News named him the NL Pitcher of the Year.

Pollet was a lefthanded stylist rather than a power pitcher, and was known for sharp control and a fine changeup. His catcher in his early years with the Cardinals, Walker Cooper, said, “Pollet’s change actually moved up and in on a righthanded hitter.” Jackie Robinson credited him with “the best changeup in the league.” Joe Garagiola, who caught Pollet on three teams, called him “an intelligent pitcher.” In pre-game meetings, Garagiola remembered, “He didn’t say how he’d pitch the hitter, or what he’d throw him, but where to play the batter.”

In a purple flight of fancy, longtime St. Louis writer Bob Broeg described Pollet as having “the sensitive features of a symphony violinist.” Broeg soared on: “The virtuoso of variable velocities, he can throw his fast ball and curve at several disconcerting degrees of speed, keeps batters off stride constantly and he’s got the courage to throw his change of pace and get it over the plate when he’s behind in the ball and strike count.”

He earned a raise to a reported $25,000 in 1950, but had to hold out until the first week of spring training to get it. His 3.29 ERA was 30 percent better than the league average, but his record slipped to 14-13 as the Cardinals dropped to fifth place. That cost Eddie Dyer his job. St. Louis’s attendance had fallen by 300,000 and Fred Saigh cut salaries across the board. When Pollet balked at a pay cut, Saigh called him “unreasonable” and pointed out, accurately, that 12 of the lefthander’s 14 victories had come against losing teams. Pollet held out until just before opening day, and Saigh put him on the trading block.

After an 0-3 start in 1951, he was swapped to the last-place Pirates a few days before his thirtieth birthday with reliever Ted Wilks, outfielder Bill Howerton and infielder Dick Cole for outfielder Wally Westlake and lefthander Cliff Chambers. He joined his former teammate, righthander Murry Dickson, who had been sold to Pittsburgh in 1949.

On June 22, 1951, Pollet was warming up to start against Brooklyn when several lights in the Forbes Field outfield blinked out. After repairs were made, he delivered the first pitch at 10:44 p.m. The game was interrupted by rain after midnight, but Pollet came back to the mound after a 36-minute delay. Brooklyn won 8-4, with the last out recorded at 1:56 a.m. It was the latest completed game in major league history to that point.

The highlight of his season came on August 28, when he stopped the Giants’ 16-game winning streak with a six-hit shutout. The Giants were surging from behind to catch the Dodgers and win the pennant on Bobby Thomson‘s “shot heard ’round the world.” At the other end of the standings, Pollet went 6-10 for Pittsburgh after the trade with an ugly 5.04 ERA. Dickson’s 20 wins helped boost the Pirates to next-to-last. Sportswriter Milt Richman wrote that Pollet was “now considered strictly a junk pitcher.”

Pittsburgh reclaimed last place in 1952 as Pollet lost 16 games against seven wins, with a 4.12 ERA. Dickson went from 20 wins to 21 defeats for a team that lost 112 games.

In June 1953 Pollet’s ERA was above 10 when he was traded to another perennial loser, the Chicago Cubs, in the biggest deal of the year. Branch Rickey sent Pittsburgh’s best player, Ralph Kiner, along with Pollet, catcher Joe Garagiola, and outfielder George Metkovich to Chicago for outfielder Gene Hermanski, catcher Toby Atwell, first baseman Preston Ward, third baseman George Freese, outfielder Bob Addis, pitcher Bob Schultz and cash estimated at $100,000 to $150,000. Kiner had won or shared the NL’s home run championship in each of his first seven seasons, but Rickey wanted to dump his $65,000 salary. Rickey had told him, “We can finish last without you.” He was right.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer J. Roy Stockton said, “Pollet is well over the hill.” He was 32. He served as a spot starter and reliever for the Cubs over the next two-and-a-half seasons until the club released him in the fall of 1955.

His former Cardinal teammate Marty Marion, manager of the White Sox, gave him a tryout the next spring. Chicago released him in May, but re-signed him a week later after trading two pitchers. The White Sox dropped him for good in July, but he caught on with the Pirates. He wasn’t ready to quit, as he told a reporter: “I have six children to support and they cost money. Our milk and food bill alone is $225 a month. And with September coming up, they’ll all need new clothes.” The Pirates were still where he had left them, in last place. He pitched creditably in relief, but was released after the season and retired. He had won 131 games and lost 116; his 3.51 ERA was 13 percent better than the league average.

He returned to full-time work with the Eddie Dyer Insurance Agency. Dyer made Pollet and former Cardinal Joffre Cross partners in the business. Pollet’s teammates had recognized his business knowledge; they elected him player representative for the Cardinals, Pirates and Cubs. In those days the Players Association was a tame company union that did not even call itself a union. The player rep’s job involved pressing such complaints as poor showers and inconvenient scheduling, according to historian Charles P. Korr.

Pollet went back to baseball in 1959 when the Cardinals’ new manager, Houston resident Solly Hemus, named him pitching coach. In spring training The Sporting News credited him with “a new idea:” counting pitches instead of innings in his pitchers’ exhibition outings. Pitcher Jim Brosnan wrote, “Howie is a quiet, soft-spoken gentleman, a type not ordinarily given to accepting coaching jobs.” Longtime reliever Lindy McDaniel said Pollet switched him from a sidearm delivery to overhand, enabling him to put more movement on the ball.

Hemus, a firebrand in the Leo Durocher mold, alienated many of the players and was fired midway through the 1961 season. His successor, Johnny Keane, was also a Houston resident and Pollet’s friend. Keane led St. Louis to the world championship in 1964, but it was a year of tumult. Bing Devine, the general manager who built the championship team, was fired in mid-season and the owner, August A. Busch Jr., was planning to replace Keane with Durocher until the club got hot late in the season. After the Cardinals beat the Yankees in the World Series, Keane abruptly quit to become the pinstripes’ new manager.

Pollet left the Cardinals to join the Houston Astros as pitching coach in 1965, then went back to the insurance business. Eddie Dyer had died in 1964, and Pollet, Cross and Eddie Dyer Jr. ran the agency.

Howard Pollet died at age 53 on August 8, 1974, after a long illness. He was survived by Virginia, his wife of nearly 33 years, five sons and two daughters.

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here. It also appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

The Associated Press, stories in The New York Times, New York World-Telegram, The Washington Post and Chicago Tribune.

The Sporting News, various issues, 1939-1974.

Unidentified clippings in Pollet’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Jim Brosnan, The Long Season. Harper & Row, 1960.

James N. Giglio, Musial: From Stash to Stan the Man. University of Missouri Press, 2001.

Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis. Spike/Avon Books, 2000.

Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Fireside/Simon & Shuster, 2004.

Charles P. Korr, The End of Baseball as We Knew It. University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Larry Moffi, “Mel Parnell,” in This Side of Cooperstown. University of Iowa Press, 1996.

Frederick Turner, When The Boys Came Back. Henry Holt and Co., 1996.

U.S. Census, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, 1920.

Full Name

Howard Joseph Pollet

Born

June 26, 1921 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

August 8, 1974 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.