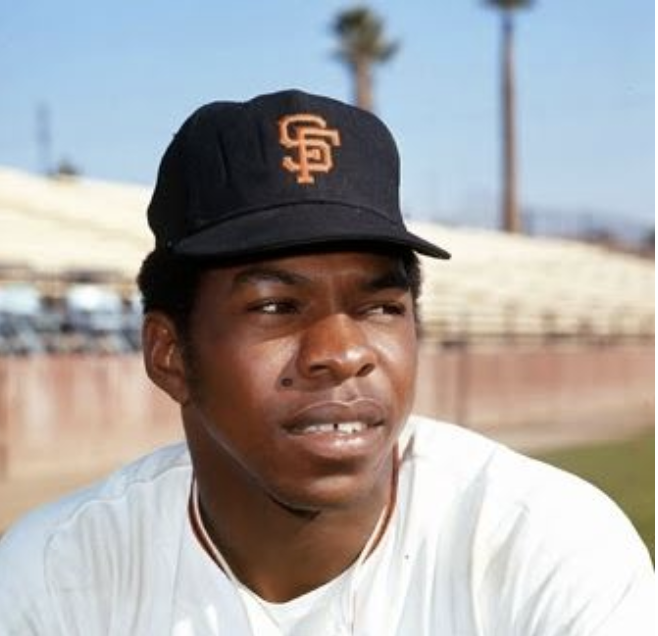

Jake Brown

Jake Brown deserves to be remembered as a profile in courage. A gruesome industrial accident in February 1974 could well have ended his baseball career. Yet even though his left forearm was nearly severed, Brown came back after surgery repaired the limb. A catcher by trade, he could no longer play behind the plate, but his batting was still strong despite the loss of muscle tissue. As an outfielder, Brown made it to the majors in May 1975 and spent the rest of the season with the San Francisco Giants. He got into 41 games, mainly as a pinch-hitter.

Jake Brown deserves to be remembered as a profile in courage. A gruesome industrial accident in February 1974 could well have ended his baseball career. Yet even though his left forearm was nearly severed, Brown came back after surgery repaired the limb. A catcher by trade, he could no longer play behind the plate, but his batting was still strong despite the loss of muscle tissue. As an outfielder, Brown made it to the majors in May 1975 and spent the rest of the season with the San Francisco Giants. He got into 41 games, mainly as a pinch-hitter.

Brown’s playing days ended after he returned to the minors in 1976. Five years later, he died from leukemia at the age of 33.

Jerald Ray Brown was born on March 22, 1948 in Sumrall, Mississippi. A few months later, his family moved to Houston. Brown’s father, Moses, worked in this major port as a longshoreman.1 His mother was Geneva Evans Brown (it’s not known how many siblings he had).2

A natural athlete, young Jake Brown played basketball and football as well as baseball at E.O. Smith Junior High and Wheatley High in Houston. “I probably would have been a football coach if I hadn’t gone into professional baseball,” he said in 1971. “I still like football. It’s a great game.” He had good size for the gridiron at 6-feet-2 and 200 pounds when fully grown. Yet baseball was his favorite.3

Brown played outfield while growing up, but he became a catcher largely because his older brother Eugene was a pitcher. Jake had to catch Eugene around home all the time whether he wanted to or not, and pretty soon they formed a battery in games.4

The Minnesota Twins selected Jake in the 33rd round of the amateur draft in June 1967. Instead, he chose to go to Southern University, a historically black college in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. There he met the woman who’d become his wife, Janice Johnson from New Orleans.5 It’s not certain when Jake and Janice got married, but it happened no later than 1972, probably in Louisiana.6 After she graduated, Janice Brown became a schoolteacher.7

The Southern Jaguars were champions of the Southwestern Athletic Conference in baseball in 1969. They were 17-2 in conference play and 28-4 overall that season. Brown led the team in homers (7) while batting .312. His 26 RBIs were second-best on the squad after shortstop Lee Richard.8 The catcher’s defense also earned him a nickname: “Chopper” — because he cut down runners trying to steal.9

Southern then faced Northeast Louisiana State in a three-game playoff. At stake was the championship of NAIA District 30 and a berth in one of eight area tournaments. The matchup was notable because it was the first head-to-head meeting between athletic teams from predominantly white Northeast State and predominantly black Southern. Their track squads had met before but always in multi-team meets.10 Unfortunately, the Jaguars lost two straight and failed to advance.11

The Giants made Brown their first-round pick in the June 1969 secondary draft. Hugh Poland, the scout who signed Brown to his first contract, had been a catcher himself. Though Brown was still a year short of his degree, a couple of years later he noted that he still wanted to go back and get it.12 Following the 1971 season, he returned to Southern for his senior year.

Brown made an immediate splash in pro ball. On July 16, in his first game for Decatur of the Midwest League (Class A), he homered. From July 23 onward, he really impressed manager Frank Funk as a major-league prospect, hitting six more round-trippers in a span of nine days.13 He had eight in just 27 games for the Commodores and added three more after being promoted to Fresno (high Class A) for the last few weeks of the season.

Returning to Fresno in 1970, he was the All-California League catcher, cracking 17 homers while hitting .259. After playing in the Arizona Instructional League that winter, he climbed to Amarillo (Class AA Dixie Association) in 1971. In spring training that year, he got his biggest satisfaction as a pro to that point by hitting three homers in a game. He liked his manager, Andy Gilbert, saying, “He always likes for you to hustle and I feel relaxed playing under him. He gets along good with the players.”14

Brown also assessed himself. “I know I have a lot to learn and need experience, but I have confidence in my ability. I think I can do it all. I can run, throw and hit. Few catchers can run. Some of them can handle the defensive work and throw but can’t hit. Some can hit but can’t throw. I feel I just need to keep working hard and be consistent.”15 He lifted his average to .284, though his power decreased some (11 homers).

The Giants invited Brown to work with the big club in spring training in 1972. He was then assigned to Phoenix of the Pacific Coast League, the organization’s top farm team. There he hit .289, but with just four homers. There was a big reason for that drop, though — Phoenix Municipal Stadium then had some of the longest field dimensions in Organized Baseball. It measured 360 feet down the lines, 412 to the power alleys, and 430 to center. To hit a home run to straightaway center, the ball had to clear a 55-foot wall. When Phoenix Muni was built in 1964, Giants owner Horace Stoneham had a large say in its design. He thought that a roomy field showed whether somebody could play or not.16

In the winter of 1972-73, Brown played with Escogido in the Dominican Republic, but he was there for just part of the season.17 One may conjecture that he was needed at home. His wife had given birth to their first child, a daughter named Rachelle, in September 1972.

Brown returned to Phoenix for a second year in 1973 after competing for a backup job behind Dave Rader in camp. He’d hit well in spring training, as John D’Acquisto, then a Giants pitching prospect, remembered in 2022. “I once had the pleasure to see Jake Brown take BP with an aluminum bat when they first came out to test in spring training. Jake hit a ball so hard he dented the bat. I was by the cage and looked at it with [manager] Charlie Fox. He asked me what I thought. I told him a guy like Jake Brown could kill someone if he hit that ball up the middle. He also cracked the bat where the dent was. Unbelievably strong human being. Loved Jake…great guy.”

Brown followed up with a solid .290 average during the regular season. He lifted his RBI total from 47 to 80, even though his home run output remained low (four). The distances to Phoenix Muni’s fences were shortened in 1980, but during the 10 years from 1970-79, an average of just 46 homers a year were hit there. By contrast, the average was 113 home runs a year in the other PCL parks.18

In an article that December about the Giants’ winter roster, Brown was described as valuable because of his potent bat.19 Again he was in the running for a reserve catching job with San Francisco. It was noteworthy, however, that he’d played mainly outfield in the second half of the 1973 season. Brown later said that Willie Mays convinced him one day to learn to play there (at some point before the veteran star was traded in May 1972).20 He’d seen some outfield action in 1970-72, but that increased after Phoenix acquired veteran catcher Danny Breeden in June 1973. Rosy Ryan, the team’s general manager, said that the Giants wanted to start giving Brown some work at first base and in the outfield because they considered his speed one of his best attributes and feared he would lose it if he spent too much time behind the plate. Brown did not play first for Phoenix, though he did appear there on occasion in later years. But Ryan was oddly prophetic in saying that Brown’s future lay in the outfield.21

A few weeks before pitchers and catchers reported in 1974, Brown’s accident happened while he was working at a sheet-metal plant in Houston. A couple of weeks after the Giants called him up, he told beat writer Pat Frizzell of the Oakland Tribune how it came about.

“I was driving a Caterpillar. Another vehicle crowded me over. My left arm got caught between the Cat and a wall.” In this account, it was sliced through almost completely, just above the wrist. Only a few ragged shreds held the arm together.22

On the same day, however, Brown described it differently to Bucky Walter of the San Francisco Examiner. He said, “The arm was caught between a sheet of metal and a lathe. It was completely sheared off.” This story had the location just below the elbow.23

Whichever way it happened, “I didn’t pass out,” Brown told Frizzell. “I just told myself, ‘This is the end of my baseball career.’ It’s the first thing I thought about.” While Brown cradled his left arm with his right, his co-workers called an ambulance. It got there quickly and rushed Brown to the hospital. “I was groggy but fully conscious,” he recalled. “I was put under anesthetic at about 5:30 in the afternoon, I think, and didn’t come out of it until three A.M.”24

Brown credited Dr. Richard Eppright, an orthopedic surgeon from Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine, for a wonderful job. Eppright had to cut out a lot of tissue because gravel and dust got into Brown’s arm during the accident. Even so, when Brown woke up and saw his left hand attached once again, he said to himself, “I’ll still be able to hit!”25

It’s also notable that the first report after the injury downplayed its severity. Jack Schwarz, administrative secretary for the Giants’ farm system, said that the arm was merely “broken in two places.”26 Various other media outlets subsequently repeated that description.

Brown remained in the intensive care unit for some time and was in the hospital for about three months altogether. He told Bucky Walter, “What can I say about their care and solicitude that would be enough to express my gratitude?”27 He began daily therapy and gradually built up strength in his left arm. Meanwhile, he said that the Giants organization was very supportive. “They were great. They never gave up on me. They kept calling me occasionally. I’m very grateful for this.”28

Determined to get back into baseball, Brown persevered with his exercise program. He reached the point where he carefully began throwing and trying to swing a bat. He observed, “I always had a very strong right hand and arm. I got my power as a hitter from that.” He turned to using a fatter bat, giving him more grip.29

During the 1974 season, whenever the Giants played at the Houston Astrodome, Brown used to visit some of his friends from the minors. “The majors looked pretty far away then,” he said. Yet when spring training 1975 rolled around, Brown reported to the Giants’ minor-league camp in Casa Grande, Arizona. He found that his reflexes as a catcher were impaired. So he moved to the outfield full-time.

To start the 1975 season, San Francisco assigned Brown to Class AA Lafayette in the Texas League. He hit well there, while as of mid-May, Giants reserve outfielder Horace Speed was hitting just .133. Thus — even though his left arm was still diminished — Brown was called up to the majors at last at age 27.

Brown spent the rest of the season at the top level. Of his 48 plate appearances, more than half came as a pinch-hitter. He also pinch-ran six times. He played in 14 games as an outfielder, including six starts. In late May, he got a two-game look in right field while Bobby Murcer sat out with a muscle knot in his back.30 Then on June 1 he got a last-minute opportunity in left. The regular there, Brown’s old minor-league teammate Gary Matthews, broke his thumb in pregame horseplay. Shadow boxing with Derrel Thomas escalated into a scuffle.31

That same day at Jarry Park in Montreal, also taking Matthews’ cleanup spot, Brown got the biggest of his nine hits in the majors. The three-run double off Dave McNally in the first inning gave San Francisco its first lead in a 13-5 win. In the bottom of the third inning, however, Brown had to leave the game after crashing into the left-field fence while chasing a long drive by Larry Parrish. “I had the ball,” he said, “but I hit a steel support pole and was knocked out.” The ball bounced out of Brown’s glove and over Jarry’s low fence for a home run.32

Brown suffered a depressed right cheekbone — a photo showed him feeling the tender part of his face while lying supine — and underwent surgery.33 He returned to action on June 13 but started just three times over the remainder of the season, including both ends of a doubleheader at San Diego on June 24. In 16 at-bats after that, all as a pinch-hitter, he had just two hits, though he also drew three walks in that role. One wonders whether the vision in his right eye, which the cheekbone injury had blurred, got back to 100%.34

For the 1976 season, Brown was optioned back to Lafayette. In mid-June, the Giants traded Willie Montañez, Craig Robinson, Mike Eden, and a player to be named later to the Atlanta Braves for Darrell Evans and Marty Perez. At the end of that month, Brown completed the deal.35 He finished out the season with Savannah in the Southern League, also a Class AA circuit.

Right after that season ended, the Browns welcomed their second child, Jerald Jr. Family considerations may have been a factor in his decision to quit playing.

After baseball, Brown returned to Houston, where he worked as a plant operator for a chemical company. It is not presently known whether he kept involved with baseball at any level.

Brown was diagnosed with leukemia in 1980. After a 20-month battle with the disease, he died from its complications on December 18, 1981. He was interred in Houston’s Paradise North Cemetery.

Jerald Brown Jr. inherited athletic talent, and because he reached 6-feet-8 in height, it was best used in basketball. As a high-schooler in 1996, he won the “Mr. Basketball” award for Texas and was named a McDonald’s All-American. He then played college hoops at Texas A&M, followed by several years in overseas leagues. After his playing days ended, he got into coaching youth basketball.

Jake Brown labored in obscurity during much of his baseball career and died far too young. His passing also attracted just the barest mention in the Houston newspapers. Yet his love for and dedication to the sport still shine through. As he said in 1971, “I enjoy playing every baseball game. I enjoy just practicing.”36

Originally published in November 2019. Updated on January 20, 2022.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Chris Rainey, who also helped obtain one of the key source articles. Continued thanks to Eric Costello for additional help in research.

Additional thanks to John D’Acquisto for his memories (e-mail, January 19, 2022).

Sources

Death certificate and other materials are in Jake Brown’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

www.mylife.com

www.ancestry.com

www.findagrave.com

Notes

1 Putt Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown,” Amarillo Globe-Times, June 1, 1971: 10.

2 Geneva Brown’s obituary in the Houston Chronicle (May 9, 2008) was very brief and omitted family details.

3 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

4 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

5 Facebook page, Janice Johnson Brown.

6 An item in Brown’s Hall of Fame Library file that includes his 1971 statistics shows him as married. There is no record that the marriage took place in Texas, and online availability of Louisiana marriage records is very limited.

7 Pat Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story,” Oakland Tribune, May 29, 1975: EE-35.

8 “Northeast, Southern Open Baseball Series in Monroe,” Shreveport Times, May 22, 1969: 24.

9 “Every Day Action ‘Jake’ with Slugger,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald, August 6, 1969: 48.

10 “Northeast, Southern Open Baseball Series in Monroe.”

11 “Tribe Plays Two Games in Tourney,” Monroe (Louisiana) Star, May 29, 1969: 17.

12 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

13 “Every Day Action ‘Jake’ with Slugger.”

14 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

15 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

16 Bob Crawford, “The man out in left field,” Arizona Republic, August 7, 1977.

17 Roosevelt Comarazamy, “Dodger Holdover Rau Sparkling with Licey,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1972: 63.

18 “PCL Giants unveil shorter dimensions,” Arizona Republic, May 3, 1980: D2. Even the so-called “smaller” dimensions were still very spacious: 345 feet down the lines, 390 up the alleys, and 410 to center.

19 Pat Frizzell, “Giant Roster Has Homegrown Flavor,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1973: 53.

20 “Southern League,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1976: 36.

21 Bob Eger, “Giants Swap Frank Johnson to Islanders,” Arizona Republic, June 5, 1973.

22 Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story.”

23 Bucky Walter, “A Giant’s Medical Miracle,” San Francisco Examiner, May 29, 1975.

24 Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story.”

25 Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story.”

26 “Brown to Miss Giants’ Season,” Arizona Republic, February 2, 1974.

27 Walter, “A Giant’s Medical Miracle.”

28 Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story.”

29 Frizzell, “A Giant’s Untold Story.”

30 Walter, “A Giant’s Medical Miracle.”

31 Pat Frizzell, “Giant Garden Now Disaster Area,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1975: 8, 12. Art Spander, “Giants Copy A’s Formula — Crab a Lot, Win Often,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1975: 14.

32 Frizzell, “Giant Garden Now Disaster Area.”

33 “It Hurts Here,” San Mateo (California) Times, June 2, 1975. “Giants Lose Matthews, Brown,” San Mateo (California) Times, June 2, 1975. Frizzell, “Giant Garden Now Disaster Area.”

34 Bucky Walter, “Murcer new S.F. casualty,” San Francisco Examiner, June 13, 1975.

35 “Giants ship Brown to Braves’ farm,” San Francisco Examiner, June 28, 1976.

36 Powell, “Brother’s advice helped Brown.”

Full Name

Jerald Ray Brown

Born

March 22, 1948 at Sumrall, MS (USA)

Died

December 18, 1981 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.