Jane Jarvis

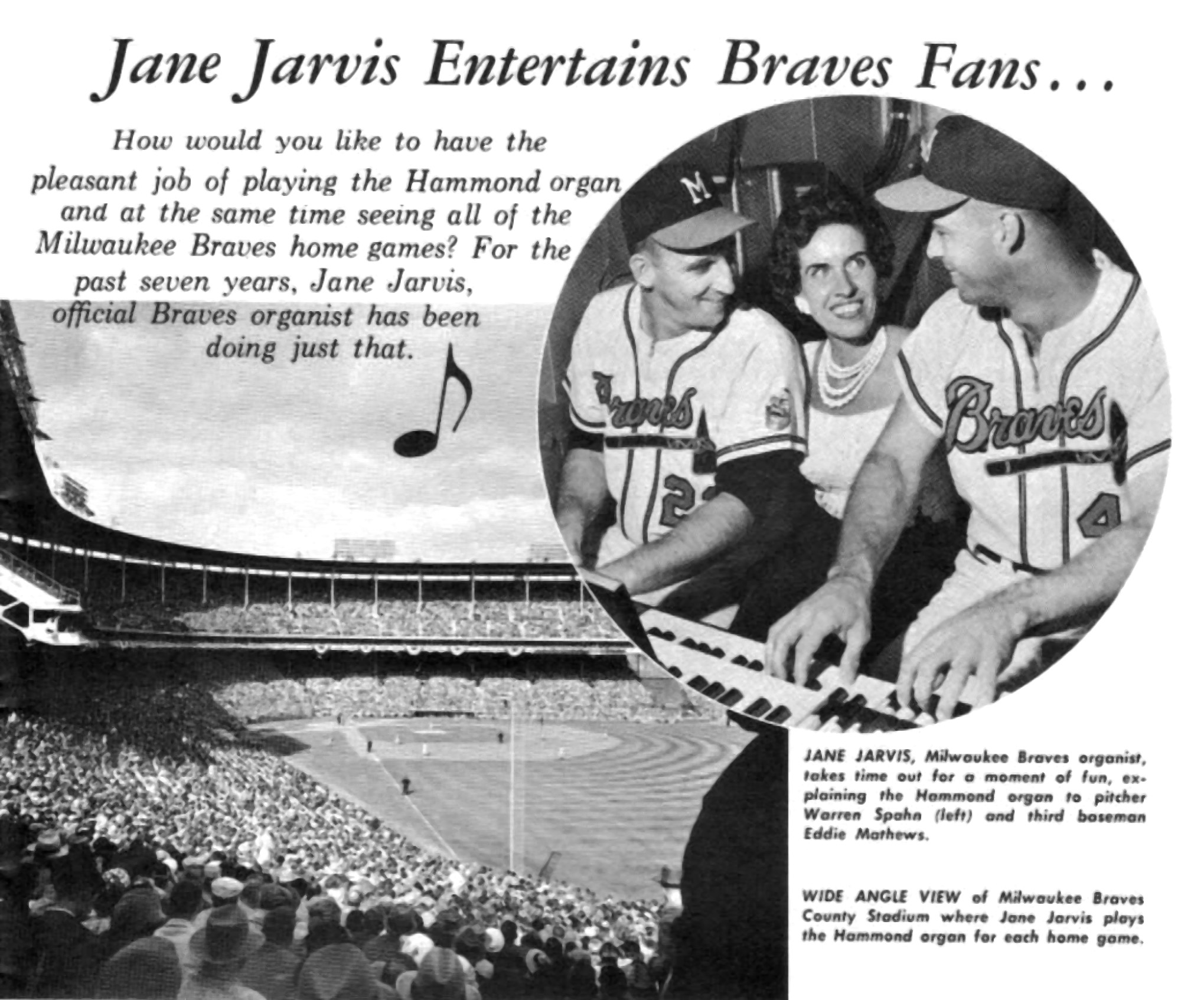

For generations of fans, the sound of an organ evoked a trip to the ballpark. One of the best-known, best-loved, and simply best baseball organists was Jane Jarvis (1915-2010). Jarvis attracted most attention during her long tenure with the New York Mets (1964 through 1979). However, the one-time child prodigy had a career in jazz both before and after her baseball days. While in New York, she also worked for the Muzak Corp., giving “elevator music” some swing.

It’s important to realize, though, that Jarvis came to baseball with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954. She played at County Stadium through 1963 and so provided the soundtrack for both the world champions of 1957 and the National League pennant winners of 1958. Jarvis didn’t know anything about the national pastime when she started her job in Milwaukee, but she quickly learned. She became a devoted fan who heightened the crowd’s enjoyment with her apt musical selections and flair at the keyboard.

Luella Jane Nossette was born on October 31, 1915, in Vincennes, Indiana. This town is in the southern part of the Hoosier State, and her speech retained the region’s drawl.1 Her first name — which she loathed2 — came from her mother, a schoolteacher. Jane was the only child of Luella (née Johnson) and her husband Charles Nossette, a lawyer. “I believe I had prenatal influences,” Jarvis said in 1993. “My parents purposefully read poetry and listened to music. As a little bitty thing, I remember my father’s reading Shakespeare out loud to me, playing word games and speaking in rhyme.”3

As one of her obituaries noted, little Jane began picking out melodies on the piano at the age of 4. “A year later her parents, impressed, arranged for her to study classical piano at Vincennes University.” 4 Another obit added that the child could play any tune that anyone requested at a department store.5

At the age of 5, Jane discovered jazz, courtesy of her uncle’s record collection. When she was 11 or 12 (accounts vary), she won a job as house pianist for a radio station in Gary, Indiana. There she accompanied nationally known performers, such as blues/jazz/gospel singer Ethel Waters and singer/comedienne Sophie Tucker.6 In her teens she also performed in theatricals starring Karl Malden and Red Skelton.7

Jane’s parents were both killed in a road accident — a train collided with their car — when the young girl was 14. It was November 5, 1929, just a week after “Black Tuesday” in the Crash of 1929. Apparently, when Jarvis read about her father’s death in the newspaper, it was the first she knew that Charles had Native American heritage.8

After the loss of her parents, Jarvis “was basically alone in the world,” according to her friend, author Lee Lowenfish (Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman).9 “I had lots of relatives,” Jane recalled in 2008, “but they were in no position to assist me, and even if they could, they were the wrong kind of people.”10 Her musical studies sustained the teenager. She attended the Chicago Conservatory of Music, the Bush Conservatory (also in Chicago), Loyola University Chicago, and DePauw University in Greenville, Indiana.11 The depth of her musical knowledge was astounding — she could play 10,000 songs from memory.12

In June 1971 Robert Cantwell of Sports Illustrated devoted a feature article to Jarvis. He noted, “She always intended to be a concert pianist. As a girl she played with the Indianapolis and Milwaukee symphony orchestras, and she once had a concert tour through several Southern cities. The critics were approving, but they also volunteered kindly advice to the effect that she was too slight and frail to meet the rigorous life demanded of a concert pianist.”13 The blue-eyed brunette was indeed petite — 5 feet even. But as New York musician and teacher Ann Ruckert said, “As she played, she somehow became much taller.”14

Cantwell continued, “Next Jane began playing in Chicago dance bands and at cocktail lounges, but she found this more tiring than the concert stage. ‘People drank too much,’ she says, ‘and talked too much. You heard too much and saw too much and you knew too much and finally you wanted some other kind of life.’ ”15

Jane married Kenneth Jarvis, a chiropractor. They moved to the Milwaukee area in 1946, settling in Oconomowoc, a suburb about 35 miles west. They had two children, Jeanne and Brian. She took a job as staff pianist at radio (and later TV) station WTMJ.16 She had a show there called Jivin’ With Jarvis.

In 1960 Robert Cantwell wrote a broader article devoted to “The Music of Baseball.” He started by telling how Jarvis came to baseball partway through the 1954 season. “When the Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee they took with them a fine new Hammond electric organ, which they perched in a makeshift organ loft in the mezzanine box seats behind first base in County Stadium. The organ sounded fine there, but the organist became a fanatical Braves supporter and soon was directing musical Bronx cheers, raspberries, moans, groans, and advice to enemy players and managers. When he began playing ‘Three Blind Mice’ every time he disagreed with the umpires he had to go.”

That organist was an interim performer named Clarence Bosch. The Hammond, which had been in storage, was installed on May 20, 1954, and used for the first time on that date during a charity game between the Braves and the Chicago White Sox. During the 1953 season the Braves used piped-in music under the last year of a contract signed by the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, for whom County Stadium was built.

As Cantwell recounted, “The task of replacing [Bosch] fell to Joe Cairnes and John Quinn of the Braves’ staff, who listened to everybody around Milwaukee and finally selected Jane Jarvis, who — though an accomplished musician — had seen only one baseball game in her life. ‘Just don’t step on anybody’s toes,’ said Joe. ‘And always remember to play “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh-inning stretch,’ added John.”17

“I wasn’t a sports fan, and I was uncertain about doing it,” Jarvis told the New York Times in 1984. “But money overcame my worries.”18 As she told Cantwell in 1971, “They put the fear of God into me — never interfere with the game. Never never never never never never never never never.”19

A Milwaukee Journal feature in June 1957 described some obstacles in the organist’s job. For one thing, her cubicle at County Stadium had a very restricted view of the field — a slot that measured one foot by four feet. Jane’s son Brian (who also became a musician) saw her quarters when he was a young boy. In 2013, he said with a chuckle, “It was dank in there — like the inside of a battleship! There were all these wires and girders. Today there would be a law against working in a spot like that.”20 Indeed, on cold days Jarvis would play while wearing a heavy coat, gloves, and galoshes.21

In addition, Jarvis and Marvin Moran, the Irish tenor who sang the National Anthem, had a very tricky task in coordinating their timing. Moran’s microphone near home plate was about 300 feet away from the organ, which was down at the far end of the first-base mezzanine, and so the sound was delayed.22

Columnist Donald H. Dooley also wrote at length about what prompted Jane’s musical selections. One example was the infamous bench-clearing brawl that broke out in July 1956 after Rubén Gómez of the Giants plunked Braves first baseman Joe Adcock. Jarvis played “The Star-Spangled Banner” in an effort to bring players up short. In 1957 she also showed her sense of humor by breaking into “Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?” after a groundskeeper got stuck under the tarp during a rain delay and was crawling around trying to get out. The crowd loved it. 23

Various players got signature tunes for home runs. Hank Aaron had “Dance With Me, Henry.” Eddie Mathews had “California, Here I Come” because he grew up in the Golden State. Johnny Logan had “Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny.”24 When the Braves won, that prompted “Happy Days Are Here Again” or “On, Wisconsin.”25

In 1960 Robert Cantwell also dwelled on this theme. He noted that the barrage of rainouts at the beginning of the 1956 season in Milwaukee prompted Jarvis to dig deep into the catalog of watery songs. Cantwell also wrote about the campaign Jarvis waged to move the loudspeakers in from a grove of pine trees in center field (because her sound was delayed or lost to wind). But when the speakers were relocated to the stands, the fans in nearby seats suffered, and the speakers went back to the trees.26

Jarvis told the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1969, “I made up my mind that as long as I was going to be there, I’d really learn the game.” She added, “The Braves were a marvelous, precision team, a remarkable assemblage of talent. It was wonderful to watch them.” That feature also noted how she developed many lasting friendships with the players and their wives during her years with the Braves. She singled out Henry Aaron — “as exceptionally fine a person in private life as he is an athlete on the field.” 27 George Crowe, Bill Bruton, and their wives were also good friends of hers. Eddie Mathews was her favorite player and a lifelong friend.28

By means of the dugout phone, Jane also became friends with the likes of Ernie Banks, then the star shortstop (and later first baseman) of the Chicago Cubs. Starting in 1962, she also held lengthy chats with Casey Stengel, manager of the Mets, whom she would come to know even better. She joked that what worried her was, “I think I understood him.” 29

Jarvis was at the keyboard when Warren Spahn won his 300th game in 1961.30 That year, she also wrote a textbook on the organ.31

After the 1963 season, Jarvis moved to New York — “where the center of the music action is,” she said.32 She later called it “the biggest risk I ever took.”33 Previously, she had said, “I moved everything, so that it was impossible to go back.”34 She’d actually tried the Big Apple first as a 17-year-old, but got scared and went home. “No roots, no money,” she said in 1984.35

Jarvis was divorced by this time; she had previously been married and divorced twice more.36 The first marriage came when she was a teenager, and ended not long after her first child died at the age of 7; she was married again very briefly to a jazz bassist.37

Jarvis worked as a music arranger at a New York TV station until her contract expired. “Out of work, friends of mine from Milwaukee put me in touch with the only person they knew in New York,” she said in 1993. “It turned out to be a nun, who knew only one person in the music world, the president of Muzak.”38 Ann Ruckert remembered, “She started as a receptionist and wound up as senior vice president in charge of all production.”39

By that time, talk was widespread that the Milwaukee franchise would move to Atlanta. John McHale, by then the Braves’ general manager and president, apparently wanted to lure Jarvis down from New York. She declined, but McHale gave her a glowing recommendation for the job that had opened up with the Mets, who christened Shea Stadium in 1964.40 Meanwhile, the Mets’ director of promotion, Tom Meany, had also checked into Jane’s background.41 He had seen her playing while bundled up at County Stadium.

During her first year with the Mets, Jarvis wrote a tune called “Let’s Go Mets”; it became a perennial that she played just as the team was ready to take the field. She also stood up to her biggest test of endurance that season. On May 31, 1964, there was a home doubleheader against the San Francisco Giants. She started her workday around noon. The opener took a normal time, just under 2½ hours — but the nightcap went 23 innings, lasting 7 hours and 23 minutes. When the game was over, she played “Gee, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.”42

A little over a month later, the 1964 All-Star Game was held at Shea Stadium. Although Ron Hunt of the Mets went 1-for-3 as the NL’s starting second baseman, Robert Lipsyte of the New York Times wrote, “The Mets’ most significant contribution … was Jane Jarvis, who was obtained last year (straight cash, no players) from the Milwaukee Braves.”43

According to Lee Lowenfish, when George Weiss (then the general manager of the Mets) hired Jarvis, he said, “We want to give the fans good music if we can’t give them good baseball.” Lowenfish also quoted Ralph Kiner, the team’s longtime broadcaster: “In those years she was the Mets.” Mets broadcaster Gary Cohen added, “She made you feel that anything was possible.”44 Robert Cantwell’s 1971 feature talked about the interplay between the crowd and the performers on the field, and Jarvis had the ability to influence the crowd’s mood.

In 1969 the Amazin’ Mets were no longer downtrodden. As their pennant drive gathered momentum, it was in early September that the Milwaukee Sentinel caught up with Jarvis. She said enthusiastically, “I definitely think the Mets will make it next year. … We might get lucky and win it this year.”45 She was right — she took part in her second World Series championship that October.

Some of the signature tunes that Jarvis bestowed on New York players included “Mr. Wonderful” for Tom Seaver, “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” for Tug McGraw (who liked to visit Jane at her organ and ask musical questions), and “Felix the Cat” for Félix Millán. A favorite for audience participation — as it had been in Milwaukee — was “The Mexican Hat Dance.” She also slipped in more adventurous jazz offerings, such as Charlie Parker’s “Scrapple From the Apple” (for arguments between managers and umpires) and numbers by Miles Davis. Jarvis always insisted that jazz was almost all she played anyway.

After the Mets games, Jane continued to provide musical entertainment at Shea Stadium’s Diamond Club. Tommie Agee, another of her favorite players, and his wife enjoyed the scene there, as did Ralph Kiner.

Jarvis was on hand for her fourth pennant in 1973, as the Mets mounted another improbable late surge. She demonstrated her importance to the club in another way during the 1973 National League Championship Series. In Game Three at Shea, a notorious bench-clearing brawl broke out after hardnosed Cincinnati Reds star Pete Rose took out Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson on a double-play ball. When Rose returned to his position in left field, the fans heaved bottles, cans, and garbage toward him, nearly causing a forfeit. National League President Chub Feeney, in the stands, asked Willie Mays to go out on the field and calm the fans, joined by Mets manager Yogi Berra and team stars Cleon Jones, Tom Seaver, and Rusty Staub. The fans simmered down, with an extra hand from the soothing sounds of Jarvis. At one point, she played excerpts from another of her compositions, “A Prayer for Peace,” written during the height of Vietnam War protests.46

Perhaps her finest hour, however, came on the night of July 13, 1977, when she kept the fans at Shea calm after a blackout struck New York City in the midst of a heat wave.47 She was playing in the dark, but her Thomas organ still somehow had power. As the New York Times wrote, “In the depths of the blackout Wednesday night at Shea Stadium, the crowd of 22,000 was singing ‘White Christmas’ along with Jane Jarvis at the organ.”48

As Jarvis attained greater influence at Muzak Corp., she hired various jazz greats, such as Lionel Hampton, to play on sessions. In fact, said musician Ann Ruckert, “she kept everyone working, recorded the entire catalogs of tunes written by jazz musicians and also helped them set up publishing companies in their own names. We were grateful for the work, and thankful for the business information and help.”49

However, Jarvis left that firm in 1978. In 1984 she remarked, “I enjoyed producing records for Muzak. But they had a change of policy that didn’t fit in with my standards. That was why I left. I thought I’d keep the Mets job for the income, while I started building a career as a jazz pianist. But then I realized that nobody would take me seriously in jazz if I stayed with the Mets. So I left in July 1979. They had no substitute for me, and they never got one. They’ve been using records ever since.”50

“I thought I was leaving on my own volition,” Jarvis observed in 2008. “It turns out they would have let me go, because there was no organ anymore. The new owners [Doubleday & Co. bought controlling interest in the Mets in January 1980] didn’t want it. They made it clear they didn’t want the music.” She was also saddened that her beloved Thomas organ vanished. 51 Many fans wanted her back — for years at Shea Stadium’s annual Banner Day, calls for her return were visible.

According to a 1986 feature about stadium organists, Mets spokesman Dennis D’Agostino said that after Jarvis left, the team’s new ownership simply wanted to make a change, and the decision had nothing to do with market research (in contrast to the Seattle Mariners, whose marketing department made a demographic study).52 In particular, it was new general manager Frank Cashen who brought in programmed music, admitting, “I’ve never been a disciple of the organ.”53 One may debate whether preference for an organ over canned tunes is generational. Yet even though nearly 40 years have passed since Jarvis left the ballpark, fans who heard her play still reminisce fondly.

Meanwhile, as the 1980s progressed, Jarvis was doing nicely as a jazz pianist. She played regularly at a Greenwich Village supper club called Zinno, usually as part of a duo with an old friend, bassist Milt Hinton. In 1985 she also got to play at President Ronald Reagan’s second inaugural ball, as part of Lionel Hampton’s orchestra. Two years later she played on the silver screen (as “Dance Palace Musician”) in Woody Allen’s Radio Days.

In 1995 a group called the Statesmen of Jazz — featuring musicians past the age of 65 — was organized in Florida. Jarvis (who had been living in Cocoa Beach, Florida, since around 1994) became their original pianist. The group traveled around the world. At that time, Jarvis was working on an autobiography.54 Alas, that work was never finished. However, she released the last two of her five record albums, Jane Jarvis Jams (1995) and Atlantic-Pacific (2000).

In 2003 Jarvis moved back to New York City. She lived on East 50th Street in Manhattan. In March 2008 a crane collapsed, crushing the building next door. The accident killed seven people, and displaced many others, including the 92-year-old. It was a harrowing experience, but she endured with the help of friends. New York Times writer Glenn Collins called her “frail but strong of temperament. … She projected the grandeur of a Gloria Swanson with an impish soupçon of Carol Burnett.”55

Jarvis was able to return home after a little while. Early in Shea Stadium’s last season, journalists Filip Bondy of the New York Daily News and Mark Herrmann of Newsday reached Jane at her apartment and heard her reminisce about her time with the Mets. As always, she was sunny and optimistic, even though she was very sad that Shea would be gone.

Not long afterward, thanks to Ann Ruckert, Jarvis moved to the Lillian Booth Actors’ Home in Englewood, New Jersey, where she spent her final months. She still played her beloved piano — Ruckert said that she and other friends went out to the home for jam sessions.

Jane Jarvis died around 11 A.M. on January 25, 2010.56 It’s noteworthy that the New York Times selected Peter Keepnews, a noted writer on the subject of jazz and the son of prominent jazz producer Orrin Keepnews, to write her obituary. However, her passing received notice in the baseball world as well. For example, Lee Lowenfish joined various figures from the jazz scene for a memorial at Manhattan’s St. Peter’s Church in May 2010 and was one of the speakers.57 Lowenfish also delivered a talk about Jarvis at the Hofstra University conference in 2012 that celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Mets.

As interesting as this woman was in many ways, her sound is what shapes the popular memory of her. “She had some pretty good jazz chops,” said Ron Swoboda of the 1969 Mets, “but she never overplayed the organ. … What made it special was that you knew it was Jane Jarvis playing that music.” Howie Rose, who grew up listening to Jarvis before becoming a Mets broadcaster, added, “She had a different lilt to everything she played.”58

What also came through in that sound was her joy. In 1961 she called her job with the Braves “just a lark.”59 Whenever she was asked how she was doing or what her life had been like, her typical reply was, “Too wonderful for words.”

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

Thanks to Brian Jarvis, Ann Ruckert, and Lee Lowenfish for their input.

Books

Feather, Leonard, and Ira Gitler, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 edition).

Harvith, John, and Susan Edwards Harvith, Edison, Musicians, and the Phonograph (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1987).

Vaché, Warren W., Jazz Gentry (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1974).

Internet

ancestry.com

fgs-project.com

findagrave.com

allmusic.com

Finding aid, Jane Jarvis papers, Music Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (nypl.org/ead/137503)

Notes

1 Angela Taylor, “She Spends Her Day Piping In Music, Then Listens to More of Same at Home,” New York Times, March 12, 1973.

2 Lee Lowenfish, “RIP Jane Jarvis (1915-2010),” Lee Lowenfish blog, February 3, 2010 (http://www.leelowenfish.com/blog.htm?post=663182).

3 Marjorie Kaufman, “She Played the Organ, the Mets Just Played,” New York Times, January 10, 1993.

4 Peter Keepnews, “Jane Jarvis, Player of Jazz and Mets Music, Dies at 94,” New York Times, January 30, 2010.

5 Mark Herrrmann, “Mets organist Jane Jarvis remembered as creative soul,” Newsday, January 30, 2010.

6 John S. Wilson, “Pop/Jazz: From Organ Caterpillar to Jazz Piano Butterfly,” New York Times, January 20, 1984. Keepnews, “Jane Jarvis, Player of Jazz and Mets Music, Dies at 94.”

7 Barbara Laboe, “Stars head to schools,” Moscow-Pullman (Idaho) Daily News, February 20, 1996, 10.

8 Herrrmann, “Mets organist Jane Jarvis remembered as creative soul.”

9 Lowenfish, “RIP Jane Jarvis (1915-2010).”

10 Mark Herrrmann, “A good time to cherish Shea’s queen of melody,” Newsday, March 29, 2008.

11 Quite a few stories state that Jarvis went to DePaul University in Chicago. The confusion is understandable, based on both name and location. She is listed in the book DePauw University People.

12 Anthony Hiss, “Most Valuable Player,” The New Yorker, September 28, 1968.

13 Robert Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball,” Sports Illustrated, June 7, 1971.

14 Ann Ruckert, “Jazz Pianist Jane Jarvis Dies,” Annruckert.com, January 26, 2010 (https://annruckert.com/ann_ruckert/2010/01/jazz-pianist-jane-jarvis-dies.html).

15 Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball.”

16 Lee Lowenfish, “Organist Jarvis provided Shea’s soundtrack,” MLB.com, April 20, 2012 (https://newyork.mets.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20120420&content_id=29206458&vkey=news_nym&c_id=nym). “Jane and the Mets Are in There Pitching,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 8, 1969. Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball.” Keepnews, “Jane Jarvis, Player of Jazz and Mets Music, Dies at 94.”

17 Robert Cantwell, “The Music of Baseball,” Sports Illustrated, October 3, 1960.

18 Wilson, “Pop/Jazz: From Organ Caterpillar to Jazz Piano Butterfly.”

19 Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball.”

20 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Brian Jarvis, August 28, 2013.

21 Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball.”

22 Donald H. Dooley, “Musical Double Play Every Day,” Milwaukee Journal, July 21, 1957, 20.

23 Dooley, “Musical Double Play Every Day.”

24 Dooley, “Musical Double Play Every Day.”

25 Buck Herzog, “Moon Is Popular Now,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 19, 1969. “Jane Jarvis Entertains Braves Fans,” Hammond Times (magazine of the Hammond organ company), Volume 23, No. 3, 1961, 5.

26 Cantwell, “In The Mood — for Baseball.”

27 “Jane and the Mets Are in There Pitching.”

28 Hiss, “Most Valuable Player.”

29 “Jane and the Mets Are in There Pitching.”

30 Lowenfish, “Organist Jarvis provided Shea’s soundtrack.”

31 Donald H. Dooley, “Milwaukee Studio Notes,” Milwaukee Journal, December 10, 1961, 25.

32 “Jane and the Mets Are in There Pitching.”

33 Erin Walter, “Pianist Took Chances That Happened to Come Her Way,” Lewiston (Idaho) Morning Tribune, February 25, 2000, 2C.

34 “State Performers Do Well in New York,” Milwaukee Journal, February 12, 1968.

35 Ben Steelman, “Jazz has been love of her life,” Wilmington (North Carolina) Morning Star, November 29, 1984, 1C.

36 Keepnews, “Jane Jarvis, Player of Jazz and Mets Music, Dies at 94.”

37 E-mail from Lee Lowenfish to Rory Costello, August 27, 2013.

38 Kaufman, “She Played the Organ, the Mets Just Played.”

39 Herrrmann, “Mets organist Jane Jarvis remembered as creative soul.”

40 Wilson, “Pop/Jazz: From Organ Caterpillar to Jazz Piano Butterfly.”

41 Barney Kremenko, “If Mets Lose, Popular Organist Plays ‘Pack Up Your Troubles,’ ” The Sporting News, July 4, 1964.

42 Herzog, “Moon Is Popular Now.”

43 Robert Lipsyte, “Mets’ Best Off-the-Field Player Knows the Score,” New York Times, July 8, 1964.

44 Lowenfish, “Organist Jarvis provided Shea’s soundtrack.”

45 “Jane and the Mets Are in There Pitching.”

46 Lowenfish, “Organist Jarvis provided Shea’s soundtrack.”

47 Filip Bondy, “Jane Jarvis recalls the happy times and tunes at Shea,” New York Daily News, May 9, 2008. Lowenfish, “Organist Jarvis provided Shea’s soundtrack.”

48 Paul L. Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out; Mets’ Game Blacked Out In Day, Too,” New York Times, July 15, 1977.

49 Ruckert, “Jazz Pianist Jane Jarvis Dies.”

50 Wilson, “Pop/Jazz: From Organ Caterpillar to Jazz Piano Butterfly.”

51 Bondy, “Jane Jarvis recalls the happy times and tunes at Shea.”

52 Jonathan Karp, “Stadium organists pipe up,” Washington Post, September 11, 1986.

53 George Vecsey, “The New Sounds of Music at Shea Stadium,” New York Times, June 30, 1980.

54 Matt Schudel, “Statesmen Show Jazz Never Ages,” Palm Beach Sun-Sentinel, January 20, 1999.

55 Glenn Collins, “Between Organist and Keyboard, a Crane,” New York Times, March 22, 2008.

56 Ruckert, “Jazz Pianist Jane Jarvis Dies.”

57 Richard Sandomir, “Memorial Tonight for Jarvis, Mets Organist,” New York Times, May 10, 2010.

58 Herrrmann, “Mets organist Jane Jarvis remembered as creative soul.”

59 “Jane Jarvis Entertains Braves Fans.”

Full Name

Luella Jane Nossette Jarvis

Born

October 31, 1915 at Vincennes, IN (US)

Died

January 25, 2010 at Englewood, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.