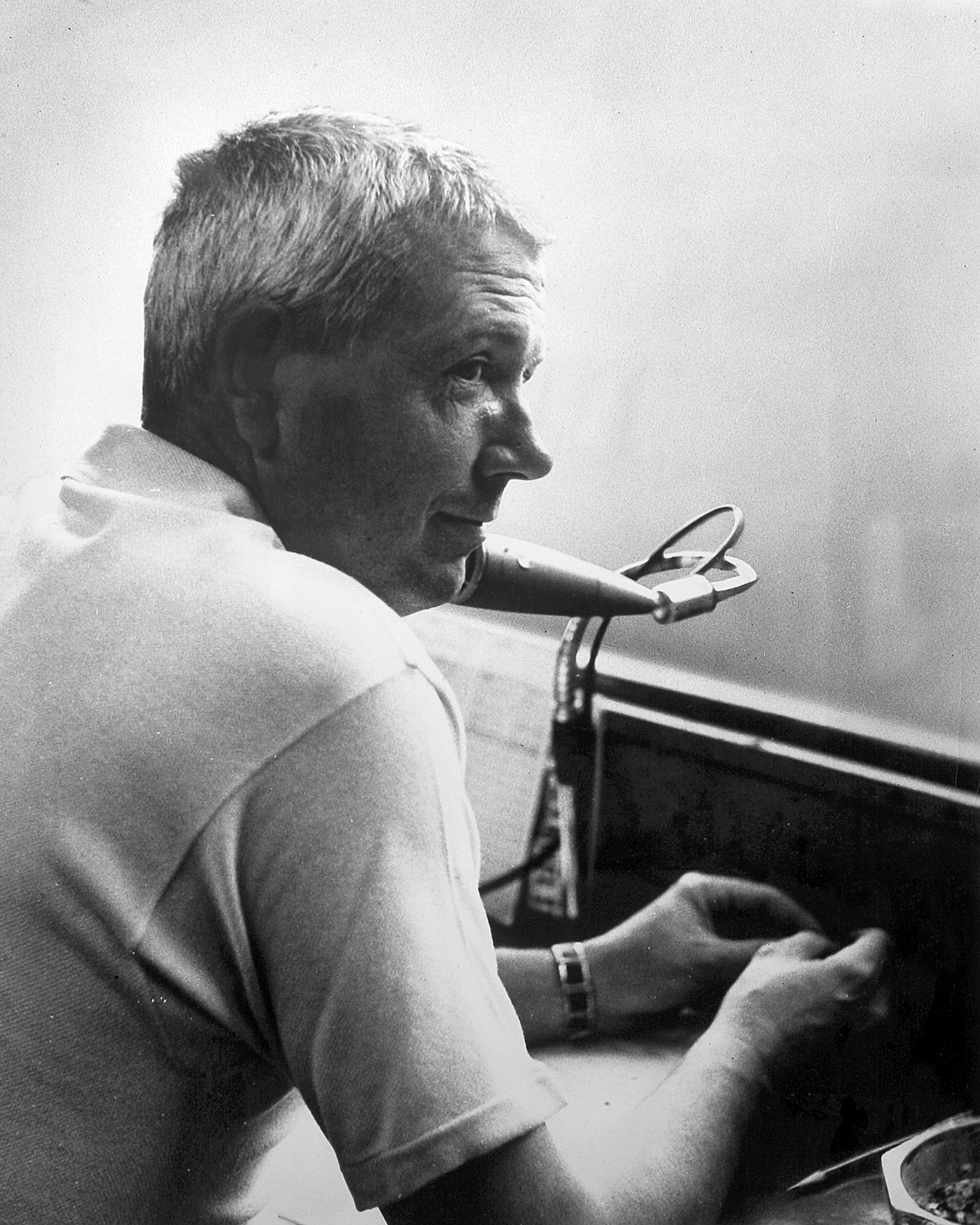

Jim Woods

From 1953 through 1956, Jim Woods was Mel Allen’s and Red Barber’s partner on New York Yankees radio/TV. One day, eying Woods’ slight overbite and gray buzz cut, Enos Slaughter jibed, “I’ve seen better heads on a possum.” In 1958 Jim moved to Pittsburgh, where announcer Bob Prince’s wife called Woods’ spouse “Mrs. Possum.” In 1974-78 the Red Sox’ Poss and Ned Martin bagged New England: Ned, wry and spry; Jim, booming like a barge. Who was better — Woods with Prince, or Martin? Did any trio top Jim, Mel, and Red? “It’s no coincidence,” said Allen. The common tie was Poss.

From 1953 through 1956, Jim Woods was Mel Allen’s and Red Barber’s partner on New York Yankees radio/TV. One day, eying Woods’ slight overbite and gray buzz cut, Enos Slaughter jibed, “I’ve seen better heads on a possum.” In 1958 Jim moved to Pittsburgh, where announcer Bob Prince’s wife called Woods’ spouse “Mrs. Possum.” In 1974-78 the Red Sox’ Poss and Ned Martin bagged New England: Ned, wry and spry; Jim, booming like a barge. Who was better — Woods with Prince, or Martin? Did any trio top Jim, Mel, and Red? “It’s no coincidence,” said Allen. The common tie was Poss.

A 1960s Avis ad blared, “We’re number two. We try harder.” In a 31-year career, Woods was number two to Allen, Barber, Russ Hodges, Jack Buck, Monte Moore, Prince, and Martin: “baseball’s peripatetic ‘second’ announcer’ who has worked for a quarter of the clubs in the majors,” wrote William Leggett. Being top gun seldom crossed Possum’s mind. Drinking and betting at the flats and harness track did. “Having fun, Jim wanted not to try harder,” Ned mused. He didn’t have to, as 1960 attests.

From 1958 to 1969 you could walk down a street in Oil City and Wheeling and Titusville and hear perhaps baseball’s all-time greatest booth. A fine play sparked Bob’s “How sweet it is!” Woods used a line he later took to Boston. “There are a reported fifteen thousand people at the game. If that’s true, then at least twelve thousand of them are disguised as empty seats.”

Some thought Poss and Prince each a maniac. Both were maniacally riveting. Like Bogart and Bacall or Abbott and Costello, one still denotes the other.

The son of Army Colonel F.A. Prince, Bob was raised at six posts and 14 or 15 schools. Later the Army brat flunked out of four universities, got a B.A. at Oklahoma, and entered Harvard Law. In 1940 Prince, 24, read about a judge who frequented a burlesque house. One night papa saw Bob, with a stripper, in a newsreel on the jitterbug. “You’re wasting my money,” pere phoned from Alabama, yanking fils from school. “Here’s $2,000. Go make a living.” Prince had another aim.

Bob’s unwritten memoir read I Should Have Never Danced with the Stripper. He should have never been scarred by a polo mallet, kicked in a rodeo, or jailed for vagrancy – but was. A pattern emerged, worthy of diffident respect. “Anything short of murder,” he said, “I’ve been there” – like Woods, later naming Bob the Gunner after the husband of a woman Prince was talking to in a bar pulled a gun.

From Harvard, Prince moved to his grandmother’s home in Zelienople, near Pittsburgh – “the only town where I could find a place to live.” Upset, Dad phoned again: “Throw that bum out of the house.” At 25 the vagabond finally settled on a career. “In the Army I’d played golf, polo, fenced. All I’d been trained to do was loaf. Broadcasting was the next easiest thing.”

By day Prince sold insurance. At night he began “[Walter] Winchellizing” on radio. Once Woods charged that boxer Billy Conn ducked opponents. The next week Conn hit him in the gut. “I can’t fight you,” said Bob, the ex-college diver, “but I’ll swim you.” Conn later asked, “What would have happened if we’d fought in the pool?” Prince: “I’d have drowned you.” Instead, he profited from a man immersed in God.

In 1948, Bucs mikeman Jack Craddock resigned to preach at revival meetings. The Gunner replaced him as lead Voice Rosey Rowswell’s aide. “We were bad, and Rosey’d trip the light fantastic,” said Bob, asking why. Rowswell: “Sponsors deserve fans, and fans deserve a show. Balls and strikes alone give ’em neither.” In an inning, he might segu? from U.S. Steel stock to poetry to a favorite song – what Prince called a “Rosey Ramble,” learning well.

“Oh, by the way,” Bob would footnote, “Clemente grounded out, Stuart flied out, and that’s the inning.” He was partisan: “Come on, we need a run.” Unpredictable: Bob won a bet by waltzing from center field to home plate in stockings, pumps, neon jacket, bow tie, and Bermuda shorts. Controversial: “On purpose,” Prince admitted. “I’d do anything to build my reputation.”

Aging, Rosey often fell asleep as Bob re-created by ticker, Prince waking him in studio if the Bucs took the lead. At Forbes Field, he pointed to a base or position “to give Rosey some idea of the ball.” From 1950 to 1957 the Pirates finished last or next to last. “Here’s to the Rosey Ramble,” Prince said after his mentor’s death in 1955. Bob’s riposte was “Gunner’s Gallop” – anything but the game.

Woods’s early life was as picaresque as Prince’s: born 1916; Kansas City Blues mascot at 4; team batboy at 8; high school, local radio score reader; freshman dropout, University of Missouri.

Dad: “Son, I hate you leaving school.”

Jim: “You won’t when I get to Yankee Stadium.”

In 1935 the ex-journalism major joined KGLO in Mason City, Iowa — The Music Man’s “River City.” By 1939 he had replaced Ronald Reagan, dealing Big Ten football for Hollywood: Poss later crowing, “Nothing like topping a prez!” Reagan’s voice soothed, like a compress. Woods’s slapped you in the face. From 1942 to 1945, he rode the Navy War Bond circuit with actors Farley Granger, Dennis Day, and Victor Mature. By 1948, Poss succeeded Ernie Harwell at Double-A Atlanta when the Georgian left for Brooklyn.

In 1949 Woods’s Crackers became the first team to air an entire home year of television. Four years later a voice phoned topping even Jim’s whiskied baritone. “Mel asks me to New York. I walk into his suite, and he’s on the phone talking to Joe DiMaggio about Marilyn Monroe.” Poss knew then he was in the bigs. In 1953 actor Joe E. Brown was to have succeeded DiMag on Yanks pre/post-game TV and air several innings. “Guess Brown should have stuck to film,” Allen said. Replacing him, Woods stuck to ball.

One day Possum was at Toots Shor’s restaurant bar, near Yanks and Dodgers owners Dan Topping and Walter O’Malley, respectively, when Brooklyn’s boss began ripping his announcer. “I hate the son of a bitch,” he said of Barber. Also gassed, Topping reciprocated: “I can’t stand Mel.” Amazed, Woods heard “the heads of baseball’s biggest teams trashing sportscasting’s then-biggest names.” O’Malley raised his glass. “I’ll trade you the SOB.” Dan replied, “I’ll give you Allen.” Next day, “sans booze,” they reneged.

The 1953 Yankees drew 1,537,811, down half a million since 1950. One cause was TV’s growth, another Allen’s sheen. Woods respected, but feared, Mel, especially his snapping fingers when something popped a cork. After Poss said Mickey Mantle “foul(ed) a ball on top,” fingers snapped. “What’d I do?” Jim said. Allen: “On top of what?” Woods: “The roof.” Mel: “Then say the roof and complete your sentence.” Jim never forgot the tutorial. “I learned to take nothing for granted and not to fear dead air, surprising for a guy famed for talking.”

Woods’s first-year team won a fifth straight World Series. Stranger than fiction: The sole Yankee to play every pre-1956 Series against Brooklyn was born there. That August general manager George Weiss told shortstop Phil Rizzuto, “We’ve got a chance to get Slaughter. What do you think?” Scooter took cyanide, saying, “Boy, getting him would be a help.” Enos replaced Rizzuto on the roster. Unemployed, Phil charmed sponsor Ballantine Beer, which told Weiss to put him in the booth. Odd man out, Woods was summoned to the GM’s office. “Jim,” George groped, “I have to do something I’ve never done – fire someone without cause.”

Stunned – “It’s a funny business. Things happen” – Woods joined the Giants and NBC’s Major League Baseball. In 1957 he did NBC’s first weekly baseball: a Brooklyn-Milwaukee exhibition. When the Giants moved to San Francisco, “I hoped to go, but they wanted someone local” to help Hodges. Instead, Poss joined Pittsburgh – his third team in as many years – “I needed a home, and here it was.” Straightway he and Gunner seared sameness the way a laser cuts dead cells. “Everybody told me, ‘Prince is out of control, you’ll never get along,’ but I decided to try him on for size.”

From the start baseball’s Ringling Brothers gilded 50,000-watt flagship KDKA with a pencil and scorecard. “That was it,” said Bob. “We’d do play-by-play – or tap dance if the game stunk.” On the last out Jim turned off his mike. “Enough of that! Booze!” The Bucs number two’s joie de vivre also applied to number one.

By 1958 the Pirates led the major leagues in percentage of area radio/TV sets in use. It was easy to grasp why. Once what Woods called “the ugliest woman I ever saw” crashed the press box, barking “I want to see f___ing [Cubs Voice Jack] Brickhouse!”

A writer fingered Bob: “There, that’s Brickhouse.”

“Are you f___ing Brickhouse?” she bellowed. The network carried every word.

Convulsed, Woods watched her leave. “Gunner, if you think that one was ugly, look at the broad she’s sitting with!” Bucs’ G.M. Joe L. Brown phoned: “You can’t call women broads on the air.” Jim countered: “Broad is the only thing you could.”

Another game Prince spied “a broad” roaming an aisle. “Poss, check that one out in black!” he howled. You’re on the air, Woods cautioned. “Geez,” Bob replied, “when I think what I coulda’ said!”

One rainy Friday NBC’s Ken Coleman, in Pittsburgh for a Saturday game, heard Prince confess, “ ‘Poss, I wish they’d call the game so I could get home and watch that John Wayne Western.’ So different than what I knew.” Once Bob ribbed some Bucs about baseball being sedentary, making Gene Freese say, “Here’s $20 you can’t dive into this [hotel] pool.” Later Woods recalled Prince clearing 12 feet of concrete from his third-floor room, asking “How’d your act check out now?” Gunner: “One way to find out,” diving from the ledge.

Poss’s play-by-play boasted similar sangfroid. “Clemente is on the move and runs it down, one-handed! A typical Roberto catch!” he bayed. “Mr. Mays is out on a tremendous play! Usually he makes a tremendous play.” Eddie Mathews, Woods noted, had said, “I hate your forkball pitcher” – Elroy Face. Don Hoak’s “battle cry was, ‘Boys, you’ve gotta keep driving’ “ – the 1960 Bucs driving to their first world title since 1925. “The Pirates clinch [the pennant]!” Poss growled on September 25 as Chicago beat second-place St. Louis. Prince and Allen telecast the World Series on NBC, though baseball banned local radio and TV – thus, Woods. Undeterred, he and Gunner later re-created Game Seven.

“The biggest ballgame ever played in the history of this city” packed 36,683 “into this old ball orchard,” Poss began. The Yankees’ lineup listed “glue-gloved” Clete Boyer; the Bucs’, “the great Roberto,” shortstop “Richard Morrow Groat,” and “in a mild surprise, at first, Rocky Nelson,” who stunned with a first-inning homer. Behind 4-0, Bill Skowron homered, Woods “never figuring out” why the pinstriped righty slugger was a left-footed kicker at Purdue. A sixth-inning four-spot gave the Bombers a 5-4 edge. “Yankee power has asserted itself, and you can feel the gloom.”

In the top of the eighth, New York swelled its lead to 7-4. Leading off the bottom, Gino Cimoli singled. Bill Virdon then lanced a “high chopping ball down to [shortstop] Tony – hits him! The ball is down, and so is Kubek!” – the ball striking him in the larynx, said Woods. “Bob, your description of the Forbes Field infield [“alabaster plaster”] again comes into play!” As Kubek traveled to the hospital, Groat “hit a line drive, left field, base hit,” Cimoli scoring: 7-5.

Each bullpen “had been the busiest place all day,” said Possum. On cue, Jim Coates, his team nickname Crazy, replaced Bobby Shantz. Bob Skinner’s bunt advanced the runners: “The tying run now in scoring position.” Nelson popped to right. With two out, “It all rides now with Roberto Clemente,” who topped “a high bounding ball to the right of Skowron! Over, and got it. Nobody to throw to! Coates did not come to cover! … Maybe that’s why they call him Crazy!” – Yanks, 7-6. Ex-pinstripe Hal Smith then worked a 2-2 count: “Long drive – deep left field!” Poss said. “Back goes ! It’s gone, baby, and the Pirates lead, 9 to 7! I don’t believe it!” The radio seemed to quiver.

Bobby Richardson and Long reached to start the ninth: the ballgame “riotous,” said Prince, again voicing. Mantle singled: 9-8. Next, Berra smacked “a hot smash down to first, backhanded by Rocky Nelson. Steps on first. And Mantle slides back into first base, and the Yankees score the tying run! Holy Toledo! What a mishmash of a play!” At 3:36, Bill Mazeroski swung at Ralph Terry’s last-of-the-inning slider. “There goes a long drive hit deep to left field!” said Gunner. “Going back is Yogi Berra! Going back! You can kiss it good-bye!“ No smooch was ever lovelier.

“How did we do it, Possum? How did we do it?” Prince said finally, din all around. Woods didn’t know – only that “I’m looking at the wildest thing since I was on Hollywood Boulevard the night World War II ended.” How to top the topper? The Bucs spent the next decade trying.

“Controversial on purpose,” Prince had defined his style. In 1966 Pirates Danny Whelan held a wiener painted green. “There,” jibed Bob, “is a [TV] picture of a grown man pointing a green weenie at Lee May.” May popped up. Trucks soon put the Weenie on their aerial. In Calcutta an Indian fakir played a pipe. The Weenie rose from his wicker basket. At Forbes, Prince once day said on-air, “Let’s put the Green Weenie on [Don] Drysdale!” A roar commenced. Big D stood, sneering, umpire Ed Vargo finally ordering him to throw. Big D: “How can I pitch with these nuts going crazy and that skinny bastard up in the booth?” Vargo: “I don’t know, but pitch.” The batter tripled. Leaving, Don shook his fist. The Pirates then flew to San Francisco via Dallas, where Bob inadvertently mentioned the word “bomb” to a flight attendant, who told the captain, who called the FBI. Apprehended, Gunner was released after the Bucs plane had left, “finally getting to ’Frisco” after 30 hours without sleep, he said. Impressed, the Black Maxers — a small group of Pirates fixated by World War I flying gear — named Bob “official bombardier.”

Would Prince ever settle down? “I am, or at least my wife thinks it’s time I did.”

Sports Illustrated described him as “shaped so distinctly in his mold that every listener feels he knows him” – like Woods. In 1968, a KDKA Westinghouse Company lawyer told them to sign “contracts so I can take them back to the office.”

Bob: “Ready?”

Jim: “Whenever you are.”

Each tore the paper. “There,” Gunner said. “Take those back to your boss.”

In the late 1960s, buying radio rights from Atlantic-Richfield Co., Westinghouse increasingly accused Poss and Prince of putting show-biz above seminar. In 1969 it spurned Woods’s pay raise – “a pissing contest with the station,” said Prince. “They and Poss were about $1,200 apart.” For a decade, Jim had felt shortchanged. “So when an offer for more came from St. Louis, I jumped.” In one sense, he regretted it. In another, he left in the nick of time.

Westinghouse began giving Gunner less promotion, less pre/post-game time, and more clients in the booth. “Some were bombed,” Prince said. “You could hear ’em in Cleveland.” He turned off a microphone, said, “Shut up,” was called a “m_____-f_____,” opened the mike, and said, “Westinghouse is making it impossible to do my job.” At the same time, Woods said that St. Louis was making it impossible to do his.

“Great baseball city, my ass,” Poss recalled. “The front office, [No. 1 Voice] Buck’s ego, how you were afraid to smile.” He left for Oakland, where the A’s won the 1972 and ’73 World Series. In November 1973 owner Charles O. Finley said that he liked homers more than Woods. “I was loyal,” said Poss, “but Finley loved the Midwest style where you scream at a foul. He said, ‘Jim, you’re a great announcer when something happens, but when nothing is going on you’re not.’”

Weiss, St. Louis, Finley: Woods pined for Pittsburgh. Instead, he signed with Boston in early 1974. That same morning, the phone rang. “I’ve thought this over,” said Finley, “and I’d like you to come back.”

“Charlie,” Jim said, “I’ve obligated myself to the Red Sox for the next two years.”

“S___,” Charlie snapped, “everybody knows those contracts aren’t worth the paper they’re written on.”

“I’m tied up! I’m not coming back,” Woods said, arriving in Boston knowing that “Sox fans like it toned down. If I did a Prince I’d have been run out of town.” Before long he won the town, noting “a couple of fans waving a Yankees banner – their parents must have raised some pretty foolish children.” Ned Martin “reminded us that baseball is a game of wit and intelligence. Woods kept alive our sense of wonder,” wrote novelist Robert B. Parker. “Between them they were perfect.” He once was describing Pittsburgh.

Power can corrupt. Popularity can confuse. “Bob thought he had the sponsors and team behind him,” said a Woods successor, Nellie King. In October 1975 Westinghouse sacked Prince, the Astros and ABC’s 1976 Monday Night Baseball soon hiring him. That spring Bob told Woods, “I wouldn’t say this to anyone else, but I’m worried,” having never called a network series. Said Poss: “You can’t do on ABC what you’ve done in Pittsburgh.” Gunner bombed, retrieving baseball only in the ’80s. “It’s just cable TV, not as many homes. But you hang in there.” Woods already had.

At Fenway Park, Poss found his next-to-Prince most pitch-perfect pal. A Philadelphian, Martin entered Duke University, joined the Marines, stormed Iwo Jima, then returned to Duke, a not-so-young man in a hurry, to major in English, read Wolfe and Hemingway, and – what? He tried advertising, publishing, and broadcasting, joining the Red Sox in 1961. Ned read poetry like Allen Ginsberg’s, had politics like John Wayne’s, and treated the Sox workforce like royalty. One moment he called Ted Williams “Big Guy.” The next evoked Shakespeare: “Good night, sweet prince.” His amalgam included a Woods-like disdain for radio jack, sham, and fools.

Ned and Poss completed each other’s sentences, communing on-air by “a hand gesture, shrug, raised eyebrow,” wrote the Boston Globe’s Bill Griffith. After a game “broadcasters, writers, and the coaching staff [gathered] during which Martin and Woods would be spellbinding with their baseball tales.” Woods called Ned “Nedley.” Martin ribbed Poss about his and Prince’s booth as bar – “Did Budweiser sponsor you, or did you sponsor Budweiser?” Like Prince’s, Martin’s synergy with Poss wowed.

In 1975. Woods passed a final-day baton: “Now Ned Martin will steer our ship with all colors flying safely into port.”

“What are our colors, Mr. [Fletcher] Christian?” Ned said, referencing Mutiny on the Bounty.

“Well, they ain’t [Finley’s] green and gold, I’ll tell you,” Poss said.

Martin: “Probably red, white, and blue.”

Sports Illustrated termed them “the best day-in, day-out announcers covering the American League” – not unlike 1958-69’s N.L. Poss/Prince. One moment Possum was gently manic: “[In] Baltimore … the Sox will play Brooksie-Baby and his merry mates.” Another hailed Carlton Fisk conquering a broken wrist. “It is gone – his first home run of the year! And look at him jump and dance! He’s the happiest guy in Massachusetts!” Jim froze anguish, too. In 1978 Bucky Dent’s homer pivoted the Boston-New York A.L. playoff game. “It is gone!” Poss said. “Suddenly, the whole thing is turned around!”

Before long, so was Woods.

In Pittsburgh, Westinghouse had been clueless about what it had. Equally inept Sox flagship WMEX (later WITS) began a pregame-show, during-inning ad blitz, and home run inning to pay a record radio rights pact. “It demeaned the product,” Ned said, “hurt the game.” More cash demanded VIP schmoozing, which he and Poss loathed. In 1978 Mariner Communications bought the station, new head Joe Scallan pining to transform Red Sox Nation.

“I’m going to change listening habits,” he informed Woods, incredulous. “What you don’t know is that I could replace you and Ned with King Kong and Donald Duck and not lose one listener.”

“Well, Joe,” said Possum, “I don’t know about King Kong, but I do believe that Donald is under contract [to Walt Disney-owned theme parks] in Anaheim and Orlando.”

Like Westinghouse a decade earlier, WITS wanted company men, not a listener’s good company. “Hit parties, ooze oil,” Woods said. “I couldn’t, nor would Ned,” refusing to prostitute. In late 1978 the flagship fired each, creating “such an uproar,” wrote the Globe, “that the fellow who fired them [Scallan] was soon gone as well.”

Moving to USA Network’s 1979-82 Thursday Game of the Week, Woods then retired, having keyed what Boston’s Shaun L. Kelly called “a radio duo, unmatched, before or since, by anybody” – save Pittsburgh. Wrote the Globe’s Bob Ryan: “You know what’s sad? … The people who ruled over them and signed their paychecks had no idea how … special Martin and Woods were” – think Poss and Prince.

Too late, KDKA rehired Gunner in 1985. “Other than my family, you’re giving me back the only thing I love.” Prince had cancer surgery, did a game, and got lung dehydration and pneumonia. “It is a sad morning,” Tom McMillan wrote June 11. “A piece of us is missing. Bob Prince is dead.” Martin did 1979-92 Red Sox TV, was axed again, retired to Virginia, and had a heart attack in 2002.

Woods’s last stop began on February 20, 1988, at 71, of cancer. He was survived by his wife, Audrey. “Leave it to Jim,” said a friend. “He had to go to heaven to find a better friend than Ned or Prince.” Not trying harder, baseball’s ultimate number two became, in a Latin phrase, primus inter pares – first among equals. Forget dancing with a stripper. From 1958 to 1969, Prince danced with an Astaire.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Material, including quotes, is derived from Curt Smith’s books Voices of The Game, Voices of Summer, The Voice, and A Talk in the Park (in order: Simon & Schuster 1992, Carroll & Graf 2005, The Lyons Press 2007, and Potomac Books 2011).

Full Name

James M. Woods

Born

October 22, 1916 at , (US)

Died

February 20, 1988 at Seminole, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.