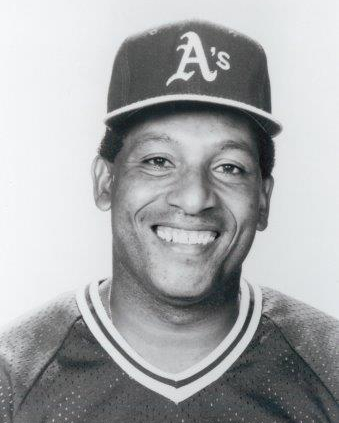

Joaquín Andújar

Joaquín Andújar was a fierce competitor and entertaining showman for 13 major-league seasons. The hard-throwing right-hander was the first starting pitcher from the Dominican Republic to earn a World Series victory, and no big leaguer won more games in the 1984 and 1985 seasons combined.

With his emotional, all-out style of play, Andújar also won a Gold Glove and homered from both sides of the plate, but his volcanic temper also led to an infamous World Series ejection that marred the four-time All-Star’s reputation. Andújar was an unpredictable athlete whose career can perhaps best be described by his own signature quote: “One word in America says it all – you never know.”1

Joaquín Andújar Sabino was born on December 21, 1952, in San Pedro de Macoris, a sugar mill town on the Dominican Republic’s southeastern coast. He was the only child of Jose Joaquín Andújar and Clara Sabino, a short-lived couple who split up before he could walk. His paternal grandparents, Saturno and Juana Garcia Andújar, raised him in their zinc-roofed home between San Pedro de Macoris’s famed Catedral San Pedro Apostol to the east, and the Iguamo River to the west.

During Andújar’s formative years, the Dominican Republic was enduring the final trimester of Rafael L. Trujillo’s three decades of dictatorship. Most of the country’s resources were firmly controlled by “El Jefe,” including the seasonal sugar industry, which was San Pedro de Macoris’s chief employer. Andújar’s grandfather worked at the Ingenio Porvenir, second oldest of the seven sugar mills dotting the city. Porvenir means “future” and, for Andújar and most of his peers, growing up to a life of labor there was indeed a probable outcome.

The 1960s were as turbulent in the Dominican Republic as they were in the United States. Andújar was 8 years old when Trujillo was assassinated in 1961. By the year he turned 13, tens of thousands of US troops occupied the country briefly to quell a Dominican civil war following a series of regime changes. “Trying to Prevent Another Cuba” was the snag line on a Time magazine cover story describing the events of 1965. Meanwhile, the first wave of Dominican ballplayers was establishing a pipeline that would soon see their country surpass Cuba as the majors’ primary source of Latin American talent.

Andújar actually preferred basketball initially but, like much of his country, he was fascinated when the 1962 San Francisco Giants surged to the National League pennant with four Dominicans on the roster. The first two big leaguers from San Pedro de Macoris – Amado Samuel of the Milwaukee Braves and Manny Jimenez of the Kansas City Athletics – debuted the same year. Baseball had been popular in the Dominican back to the late nineteenth century, but suddenly it was everywhere, and Andújar began playing as much as he could. “Without a good glove, a decent bat or a pair of cleats, because everybody is very poor,” he recalled. “We used to make a rag ball, or we bought a rubber ball and played in the streets.”2

Andújar’s first amateur club was called Jabon Hispano and, when he got older, he played for a team managed by Pedro Gonzalez, the first Dominican to play for the New York Yankees. Andújar was a switch-hitting center fielder who usually hit cleanup, an all-or-nothing free swinger with a combustible temper. Once, he destroyed his own jersey when Gonzalez took him out of a game. It was a big deal, because the incident occurred around the same time Andújar quit attending Jose Joaquín Perez High School because his family couldn’t afford to buy him pants or shoes. With his grandfather nearing retirement age, the boiler room at Ingenio Porvenir looked increasingly like the setting for Andújar’s future.

Tetelo Vargas Stadium opened in San Pedro de Macoris just before Andújar’s7th birthday. The Estrellas Orientales of the Dominican winter league played there, and Andújar spent a good chunk of his teen years shagging balls for them and studying major leaguers like Braves slugger Rico Carty up close. The facility was available to youth leagues, too, and it was there that Wilfredo Calvino noticed a particularly strong Andújar throw from center field. Calvino was a former minor-league catcher from Cuba who scouted for the Cincinnati Reds. “He asked me if I wanted to become a pitcher,” Andújar said. “I told him that I didn’t care, that the only thing I wanted was to go to the United States to make money and help my family and myself.”3

Andújar signed with the Reds in November 1969, and reported to rookie league the following summer along with two other 17-year-old Calvino signees from San Pedro. Incredibly all three of them would play in the major leagues. Santo Alcala was a tall, happy pitcher who’d room with Andújar in the minors for most of the next five years, while Arturo DeFreites was a serious, muscular third baseman who’d wallop 32 homers one year in Triple A when he filled out. On a diet of hot dogs and French fries because he didn’t know how to order anything else in English, Andújar struck out more batters than any right-handed pitcher in the Gulf Coast League in 1970, including a handful in the circuit’s all-star game. Upon returning home, he joined the legendary Leones del Escogido – winner of half of the last dozen Dominican League championships – for seven appearances before his 18th birthday.

A promotion to the Northern League Sioux Falls Packers in 1971 proved extremely challenging, however. Tougher competition, real road trips, and a manager who didn’t speak Spanish added up to a difficult season. Andújar led the team in wild pitches and was demoted to the bullpen. At the end of the season, manager Dave Pavlesic told the high-kicking Andújar , “You’re not Juan Marichal. You’d better learn how to pitch.”4

Andújar got 93⅓ innings of much-needed experience that winter for Escogido. He led the Dominican League in walks, but fashioned an impressive 2.93 ERA and the Reds noticed. While Alcala and DeFreites went to a co-op Single-A team to play for a Spanish-speaking manager, Cincinnati promoted Andújar to Double A. The Eastern League hitters were one challenge, but pitching for Les Aigles des Trois-Rivieres meant “home” games were played in the French-speaking Canadian province of Quebec. Against all odds Andújar thrived, winning seven of his first eight decisions before rolling his ankle and literally limping to a 7-6 final record.

Still hobbling in winter ball, Andújar was traded in midseason to the Estrellas Orientales. The four-player deal allowed Escogido to recover the contractual rights to Juan Marichal. Andújar was thrilled to pitch for his hometown team, which featured lots of Houston Astros through a working agreement with the National League franchise. Cesar Cedeno and J.R. Richard were two of the club’s stars that winter, but it was Estrellas manager (and Astros coach) Hub Kittle who’d have the biggest impact on Andújar’sfuture. “Everything I have, I owe to Hub Kittle,” Andújar remarked years later.5

The Reds invited Andújar to his first big-league spring training in 1973, but sent him to Triple A, where he didn’t care for Indianapolis Indians skipper Vern Rapp. “I tell (Reds farm director Chief) Bender in spring training I no like to go to Indianapolis. I told them I no like manager. He gives you hell when you lose,” Andújar explained.6

Andújar walked too many batters and in June was sent back to Trois-Rivieres, where he proceeded to show he had nothing left to prove in Double A by going 5-2 with a 1.98 ERA. He followed that up with a 2.53 mark in winter ball, where he cut down his leg kick and walk rate while learning from “El Coyote,” Hub Kittle’s nickname in the Dominican.

Back at Indianapolis in 1974, Andújar made 17 starts and 16 relief appearances as Rapp jerked him in and out of the rotation. The low point came in July when Andújar responded to an early hook by destroying a dugout water cooler, which prompted Rapp to suspend him. Andújar finished 8-8 with a 3.57 ERA and two saves as Indianapolis made it to the league finals before falling to the Tulsa Oilers. The championship series went the distance with several extra-inning contests, but Rapp used Andújar only as a pinch-runner.

Back in the Dominican, however, Kittle was more than happy to give him the ball. Andújar responded by winning six of seven decisions and the Dominican League’s native-pitcher-of-the-year honors. “They said he had a million-dollar arm and a ten-cent head. But that’s not true. He’s a very intelligent person,” Kittle observed.7

The Estrellas came up just short in their championship series as well, but Andújar was selected to accompany the triumphant Aguilas Cibaenas to Puerto Rico for the Caribbean Series. He beat Venezuela in his lone start.

Andújar arrived at spring training in 1975 with Reds manager Sparky Anderson hoping some special treatment would unlock his potential, as it had for another volatile Dominican, Pedro Borbon, a few years before. Instead, Andújar began a third straight season in Indianapolis. Before he even got into a game, Rapp told him he was going back to Double A. “Vern Rapp grabs me and says if I don’t like it I can fight him,” Andújar said. “I think to myself, Joaquín , you be making wrong move fighting with Vern Rapp.”8

Injuries limited Andújar to just 62 innings at Trois-Rivieres and, two days after the Reds won the World Series, they traded Andújar to the last-place Houston Astros for pitchers Luis Sanchez and Carlos Alfonso, neither of whom pitched a single inning for Cincinnati. Andújar went 7-2 for the Estrellas to repeat as native-pitcher-of-the-year in what proved to be his last winter with Kittle, who left the Astros organization as part of their organizational shakeup

On Opening Day 1976, Andújar made his major-league debut in – of all places – Cincinnati, walking the first two batters he faced to force in a run. He didn’t pitch much for the first two months, but beat the Reds, 2-1, with a complete-game two-hitter on June 1 for his first major-league win. He became the first Dominican ever named Player of the Week after shutting out the Cubs in his next start. By mid-July, he’d beaten the Reds twice more with complete games, and pitched back-to-back 1-0 shutouts. Pitching for a sub-.500 club, Andújar finished his rookie season 9-10 with a 3.60 ERA.

Andújar got off to a slow start in 1977, but reeled off six straight victories. With a 10-5 midseason record, he was named to Sparky Anderson’s National League All-Star squad. A pulled hamstring in his last start before the break kept him out of action, and Andújar won only once more after missing six weeks. He proved he was healthy in 14 starts that winter, rejoining the Leones del Escogido in the Dominican capital of Santo Domingo for the first time in five years. Andújar also married the former Walkiria Damaris Saez in the offseason, and expected big things from himself in 1978.

After predicting a 25-win season in spring training, Andújar pitched well early in 1978, though poor run support prevented his record from reflecting it. He hurt himself swinging for the fences during batting practice in May, however, then ticked off manager Bill Virdon by swinging too hard in his first game back and aggravating the injury. Andújar exited one game with a debilitating case of jock itch, then suffered another hamstring pull that knocked him out of action for nearly two months. After finishing a lost Astros season in the bullpen, he recovered to lead the Dominican League in complete games for Escogido and pitch in another Caribbean Series before spring training.

Andújar’santics didn’t endear him to his manager, never mind opponents, but many fans got a kick out of his gunslinger routine in which he pointed his index finger at vanquished hitters like a pistol. In his early years, he’d even pretend to blow the gunsmoke away and return the gun to his holster.

The 1979 Astros got off to a great start with Andújar excelling in a swingman role. When he finally rejoined the rotation, he won Pitcher of the Month honors in June and returned to the All-Star Game with an 11-5 first-half record. Andújar pitched in the game at the Seattle Kingdome. Over the course of the next month, he became a father when son Jesse was born, and hit his first big-league home run, an inside-the-park blast with a man aboard at the Astrodome to beat Montreal’s Bill “Spaceman” Lee, 2-1.

The Astros coughed up a 10-game division lead, however, as Andújar lost seven of eight decisions after the break and was sent back to the bullpen. Houston agreed to swap him to the World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates for aging slugger Bill Robinson at the winter meetings, but Robinson nixed the deal by exercising his 10-5 rights. Andújar didn’t know who he’d be pitching for on Opening Day, but he enjoyed another strong winter campaign for Escogido. In February he beat Venezuela in his only start to help the Dominican Republic win the Caribbean Series on their home turf.

Andújar had his first six-figure salary heading into 1980 after winning his arbitration case, but few opportunities to start after Houston signed Nolan Ryan to a free-agent contract. One year after pitching in the All-Star Game, Andújar failed to win a single game in a first half in which he rarely got to pitch at all. The Astros kept him as insurance in case somebody got hurt, which proved to be all too prescient when ace J.R. Richard suffered a tragic stroke in July. Andújar posted a 1.19 ERA in August when the Astros turned to him in desperation, but was returned to the bullpen for a third straight year by season’s end. Houston survived a one-game tiebreaker to win the National League West. When the Astros finally won a tense NLCS Game Two in Philadelphia for the franchise’s first-ever postseason victory, Andújar got credit for a save. They lost the NLCS in five games.

Andújar’swinter season ended abruptly when he got into a dispute about complimentary tickets with Escogido’s front office. The Leones won their first title in a dozen years without him, and the Astros kept making it abundantly clear that they weren’t relying on Andújar either by acquiring two more proven starting pitchers. Andújar offered to pitch for free as he languished as the last man on the pitching staff for two months. His agents implored him to wait quietly for his impending free agency. Finally, in the first week of June, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. Before he could even get into a game with his new team, major-league players walked out on strike for more than seven weeks.

When play resumed, however, Andújar won six of seven decisions for Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog and a St. Louis pitching coach he knew very well, Hub Kittle. “Before the Cardinals got me, I was like a plant that needed water,” he said. “Whitey and Hub, they poured water on me, and I grew to be a tree.”9

Andújar signed a three-year free-agent contract to return to St. Louis, and it paid immediate dividends in 1982. His control was better than ever and he was an important part of an exciting team that got off to a hot start. By the All-Star break, Andújar had the second-lowest ERA in the National League, but not enough victories to earn a spot on the team. Though he continued to pitch effectively, his record slipped to 8-10 by early August before he reeled off seven straight wins to close the regular season. His 5-0 record in September earned him NL Pitcher of the Month honors and helped the Cardinals win their division. Andújar won the pennant-clincher in Atlanta in the NLCS, then took on the high-scoring Milwaukee Brewers in the World Series.

Andújar was the only player on the field wearing short sleeves on a cold night as he carried a shutout into the seventh inning against the highest-scoring team in two decades. His evening ended abruptly when Ted Simmons hit a wicked one-hopper that caromed off Andújar’sright knee into foul territory. Writhing and screaming in obvious agony, he nevertheless became the first pitcher from the Dominican Republic to win a World Series game when reliever Bruce Sutter nailed down the final outs.

Andújar spent several days on crutches, and it appeared unlikely that he’d be able to pitch if the Series went the distance. When Game Seven of the 1982 fall classic got underway at Busch Stadium, however, Andújar was back on the mound to demonstrate why he’d been calling himself “One Tough Dominican” all season. Andújar got through seven innings with a lead, then had to be hauled off the field by several teammates after Milwaukee’s Jim Gantner profanely called him a hot dog. Six outs later, the Cardinals were World Series champions. Andújar figured his 2-0 series record and 1.35 ERA were Series MVP numbers, but the honors went to his catcher, Darrell Porter. Even one of the losing Brewers got more votes than Andújar .

In 1983 he won his first two decisions to extend his winning streak to 12 before his season unraveled due to too many overthrown, straight, high fastballs. In June the Cardinals lost leadoff hitter Lonnie Smith to drug rehab and star first baseman Keith Hernandez to a trade. Andújar was healthy enough to start 34 games, but finished the season with a miserable 6-16 record. “God is still my amigo,” he insisted. “He must be someplace else. Maybe He’s watching the American League.”10

Andújar was one of the most aggressive, and unusual, hitters in baseball history. He struck out in more than half of his at-bats, usually swinging as hard as he could. He was a switch-hitter, but not in the usual sense. “If the pitcher has good control, I will bat left-handed against a right-handed pitcher. I bat right-handed against pitchers who don’t have good control, or if I don’t know them, because I don’t want to get hit in the right arm. I bat right-handed with nobody on base because I’m a power hitter from that side. I bat left-handed with men on base so I can make better contact and drive in runs.”11

In 1984, he homered both right-handed and left-handed – including a grand slam – and won a Gold Glove. Andújar also earned National League Comeback Player of the Year honors after winning his 20th game with just two games to play in the regular season. Andújar skipped the All-Star Game to be with his ailing grandfather, and finished a distant fourth in Cy Young voting despite being the league’s only 20-game winner. After the season, he received a hero’s welcome, however, when more than 10,000 Dominicans welcomed his flight back to Santo Domingo. “I grew up here. I never moved from here. People appreciate that,” he explained. “I hope I die here, but you never know.”12

St. Louis rewarded Andújar with a three-year contract that made him just the third Dominican to average more than $1 million annually. He was the Cardinals’ Opening Day starter in 1985 and raced off to a 12-1 start that kept the Redbirds afloat in what would prove to be a season-long dogfight with the young New York Mets in the NL East. Andújar appeared on the cover of The Sporting News with his friend and fellow Dominican, Reds ace Mario Soto. Both pitchers had been involved in multiple bench-clearing incidents in recent seasons, and Andújar led the league in hit batters for the second consecutive year. In the article, titled “So Good … So Misunderstood,” Andújar said: “Nolan Ryan pitches inside, and I don’t see anybody fighting Nolan Ryan. Steve Carlton pitches inside to everybody, nobody says anything. But when Joaquín Andújar and Mario Soto pitch inside, everybody goes to the mound and fights. If they love to fight, they should go to war and fight. They should go to the Middle East.”13

Andújar’srecord was 15-4 in the first half, but San Diego Padres manager Dick Williams decided to choose his All-Star Game starting pitcher based on a one-game showdown between Andújar and San Diego’s LaMarr Hoyt. Andújar was so put off by the idea that he vowed never to attend another All-Star Game in his life. As unlikely as it was at the time, he’d never be invited back anyway. Andújar won a career-high 21 games in 1985, despite struggling through a 6-8 record in the second half. To make matters worse, in September, former Cardinals teammates Lonnie Smith and Keith Hernandez both identified him as a cocaine user in the sensational drug trial taking place in Pittsburgh.

The Cardinals went 101-61 to win the NL East and ousted the Los Angeles Dodgers in a six-game NLCS, but Andújar’sstruggles continued. He was bombed by the Kansas City Royals in Game Three of the World Series, which proved to be his last appearance in St. Louis as a Cardinal. The Redbirds nearly won their second World Series championship in four years, but blew a ninth-inning lead in Game Six following a controversial call by first-base umpire Don Denkinger. St. Louis was already trailing Game Seven, 9-0 in the fourth inning, when Whitey Herzog called on Andújar – whom he’d chosen not to start – to pitch mop-up relief with Denkinger calling balls and strikes. He gave up a single and a base on balls. The walk caused Andújar to lose his cool, charging and bumping Denkinger, and getting ejected.

Though Andújar’s41 wins over two seasons were unsurpassed in the majors, the Cardinals took the best offer they could get for him, sending him the Oakland A’s for pitcher Tim Conroy and catcher Mike Heath in December of 1985. In addition to a 10-game suspension for his World Series outburst, Andújar faced up to a one-year ban from Commissioner Peter Ueberroth in the fallout from the drug trial. Unlike the six other players – including Smith and Hernandez – facing the most severe punishment, Andújar was never called to testify.

As it turned out, Andújar missed only the first five games of 1986 before a series of injuries caused him to spend time on the disabled list for the first time in eight seasons. He talked about retirement before coming on strong to go 12-7 for an Oakland club that finished 10 games under .500.

In 1987 he arrived late for spring training, which wasn’t unusual, but injured himself going all out in his first day of drills, which was. The birth of his second son, Christopher, was about the only highlight in a season that saw him post a 6.08 ERA and average less than five innings in the 13 starts he was able to make. When Oakland general manager Sandy Alderson reflected on the trade he put together to acquire Andújar , he said, “Both teams got nothing, but our nothing was louder than theirs.”14

Andújar took a substantial pay cut to return to the Houston Astros in 1988, but endured a pulled muscle in his side and knee surgery in April alone. In his first appearance back in St. Louis since being traded by the Cardinals, he surrendered a walk-off home run to fellow Dominican Tony Peña. When he drilled Peña with a fastball a few weeks later, he was fined and suspended by NL President Chub Feeney. “There is some guy, some big guy in United States baseball, he doesn’t want me in baseball. He wants me out of the game,” Andújar said.15

Andújar’s4.00 ERA wasn’t terrible, but he couldn’t go deep enough into games to stay in the starting rotation. He kept asking for his release, but faded quietly to the end of his major-league career with a lifetime 127-118 record.

In 1989 no team would guarantee Andújar a major-league roster spot, so he stayed home in the Dominican until the Gold Coast Suns of the newly formed Senior League of Professional Baseball offered him an opportunity. Just before his 37th birthday, Andújar went 5-0 with a minuscule 1.31 ERA to earn an incentive-laden deal and invitation to spring training from the Montreal Expos. A gimpy leg and an abscessed tooth limited him to two appearances, however, and the Expos released him before Opening Day when he made it clear he wouldn’t pitch in the minors.

When Whitey Herzog became the California Angels’ senior vice president after the 1991 season, he hired Andújar as a scout, but the arrangement proved to be short-lived. The Angels weren’t willing to invest much in Latin scouting, and Andújar still wanted to pitch. Several teams expressed interest in signing him when he made a comeback attempt with the Estrellas in late 1993, but knee problems and a freak car accident convinced Andújar that he should retire once and for all after only two starts.

Andújar continued to help young players around San Pedro de Macoris, assisting the San Francisco Giants Dominican Summer Leaguers and the Estrellas, particularly when his old friend Arturo DeFreites was their skipper. The Chicago White Sox noticed his ability to help young pitchers and brought him to spring training one season, but he refused their offer of a job when he found out it would be at the expense of one of his friends. Instead Andújar coached informally, but consistently, and played softball to keep his swing in shape. Investments in a construction business, and later a trucking company, did little except drain his bank account, however. In 2003 Andújar returned to St. Louis for the first time in 15 years to throw out a ceremonial first pitch at Busch Stadium to a loud ovation. “I live in the Dominican, but my heart still is in St. Louis,” he said.16

Two years later, Major League Baseball made Andújar one of 15 finalists for a Latino Legends team that would be chosen through fan voting. He finished 10th among pitchers. Andújar’slast appearance at Busch came in 2007, for the 25th anniversary of the 1982 World Series champions. St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Rick Hummel described him as looking “smaller than we remembered him.”17

The Hall of Fame of San Pedro de Macoris inducted Andújar as a member in 2011, and the Caribbean Series made him a member of its Hall of Fame a year later. Andújar missed both ceremonies for undisclosed health reasons. The truth was that diabetes was taking a toll on “One Tough Dominican.” Andújar also went through a divorce, lost his big home and moved to an apartment in Santo Domingo, where he survived on his major-league pension.

Joaquín Andújar died on September 8, 2015. Many sports fans in the United States learned the news from the Instagram feed of Robinson Cano, the most prominent player from San Pedro de Macoris at the time. Cano called it a “big pain for all baseball fans, especially all Dominicans, but even more so for all of us who had the chance to know you and learn from your example.”

Just over a month before Andújar’s death, the Dominican Republic enjoyed a proud moment when Juan Marichal joined Pedro Martinez on stage at the latter’s induction ceremony at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Two of the only three Dominicans with multiple 20-win seasons stood smiling and holding their country’s flag aloft. Precisely 15 years after Marichal’s last 20-win season, and 15 years before Martinez’s first, Andújar won 20 for the first of two consecutive years. “Andújar was in the middle of every dream I had because he was one of the best pitchers we ever had in the Dominican Republic,” remarked Martinez.18

Notes

1 Kenny Hand, “Andújar Gets Shot Against L.A. Tonight,” Houston Post, September 9, 1980: 2D.

2 Julio Gonzalez, “Joaquin: Facing the Future With a View from the Past,” Oakland A’s Magazine, Volume 6, Number 2: 14.

3 Gonzalez: 12.

4 Dave Pavlesic, interview with author, May 31, 2006.

5 The Sporting News, November 5, 1984: 49.

6 Duke De Luca, “Andújar Slows Down Phils,” Reading Eagle, June 30, 1973: 6.

7 Rick Hummel, “ Andújar’sSecret? Daddy Knows Best,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 3, 1982.

8 Kenny Hand, “Ayyyayyaya, Joaquin. Andújar Makes Astros Happy with Jokes, Pitching,” Houston Post, May 22, 1977.

9 Steve Wulf, “Here’s a Hot Dog You’ve Got to Relish,” Sports Illustrated, January 24, 1983: 32.

10 Rick Hummel, “Andújar : God Is Still My Amigo,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 22, 1983: B1.

11 Rick Hummel, “Sport Interview: Joaquin Andújar ,” Sport, September 1985: 27.

12 Rick Hummel, “Youneverknow What to Expect From Cards’ Ace,” The Sporting News 1985 Baseball Yearbook, 120.

13 Rick Hummel, “So Good … So Misunderstood,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1985: 3.

14 David H. Nathan, The McFarland Baseball Quotations Dictionary (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 2000.

15 Neil Hohlfeld, “Could ‘Someone Big’ Be Out to Get Andújar ?” The Sporting News, June 27, 1988: 21.

16 Rick Hummel, “ Andújar’sHeart Remains in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 26, 2003.

17 Derek Goold, “Colorful Cardinals Ace Andújar Dies,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 8, 2015.

18 Joey Nowak, “Former All-Star Pitcher Joaquin Andújar Dies,” mlb.com, September 8, 2015. mlb.com/news/joaquin-Andújar -dies-at-62/c-148062060.

Full Name

Joaquin Andujar

Born

December 21, 1952 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

Died

September 8, 2015 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.