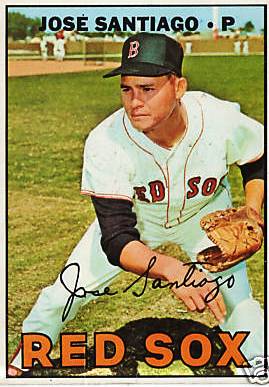

José “Palillo” Santiago

In José Santiago’s first appearance on a major-league mound, he entered a 6-6 tie game against the New York Yankees to pitch the eighth inning. It was September 9, 1963 and he got Elston Howard to ground out back to him on the mound, Joe Pepitone to line out, and Clete Clete Boyer to strike out. When Kansas City scored in the bottom of the eighth, Santiago picked up the win. It was a nice way to start an eight-year career in major-league ball, three years with the Athletics and five with the Red Sox.

In José Santiago’s first appearance on a major-league mound, he entered a 6-6 tie game against the New York Yankees to pitch the eighth inning. It was September 9, 1963 and he got Elston Howard to ground out back to him on the mound, Joe Pepitone to line out, and Clete Clete Boyer to strike out. When Kansas City scored in the bottom of the eighth, Santiago picked up the win. It was a nice way to start an eight-year career in major-league ball, three years with the Athletics and five with the Red Sox.

José R. Santiago Alfonso was born in Juana Diaz, Puerto Rico on August 15, 1940. Known as “la ciudad de los poetas” (the City of Poets), Juana Diaz is a community roughly 10 miles northeast of Ponce in south-central Puerto Rico. The city is also known as “la Ciudad del Jacaguas” after the river of the same name which flows through its fields on the way to the sea. Juana Díaz produces sugar cane and beige marble, considered one of the finest marbles in the world.

His father Alejandro Santiago, ran a kind of general store that served workers on the sugar cane plantation. “He’d sell all kinds of products in it. He would sell the beans and the rice and everything you can think of,” José recalls.1 Alejandro Santiago ran the store with his wife, Merida Alfonso. The two raised three children: Betty, José, and a younger boy, Alejandro, Jr.

Juana Diaz was a good-sized community back then, around 30,000 to 40,000 people. It’s grown to about 50,000 today. The Santiagos were well-enough off economically relative to others, but José still learned humility as a young boy. His first memories of baseball date back to being 5 or 6 years old. As he grew older, the kids in the Lomas neighborhood where he was born benefited from José’s father’s passion for baseball. Alejandro had played amateur baseball, a third baseman. “At the time, it was tough to play baseball,” José remembers. “We didn’t have any equipment. We had to get the sacks that they bring the wheat in, and wash it for about three or four days and then try to make a uniform out of that. My dad bought some bats and baseballs and some gloves for us, and that’s how we started. We didn’t even have a ballpark to play. We have to go either to another city to play or to go across the river and play…it was a cow field. Cut the grass and go ahead and then just play.”

As a child, José was a very skinny boy. That caused some friends to called him “Palillo,” the Spanish word for toothpick. He played his first game on the shores of the Jacaguas River near Lomas. “We played some other barrios, some other sectors of Juana Diaz.” In high school, when classes were over on a Fridays, the team would travel by bus and play in Ponce, Mayaguez, or elsewhere.

José wasn’t always a pitcher, though. That really came in college. Right through high school, Santiago primarily played center field. “I just had a great fastball, great arm, but I didn’t know anything about pitching. I couldn’t curve nothing.” It was his father who saw him pitching one day, and said, “I think you’ve got a better chance to be a pitcher than an outfielder.” It was in college that he was able to benefit from some real coaching from Carlos Negron and Gonzalez Pato at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Puerto Rico (Catholic University of Ponce.) Another man he is quick to credit with help in pitching is Cefo Conde, who was a pitcher in the old Negro Leagues. Conde’s nephew is Santos (Sandy) Alomar, Sr.

José Santiago’s final accomplishment as an amateur player was for a Class-A team in a neighborhood called Romero. He threw a 16-inning game that he lost 3-2 against Santa Isabel. But the young Juanadino was on his way.

José Santiago became a professional baseball player in 1957. It happened when finishing his freshman year at Catholic University. According to his sister Betty, one morning José was working with her in the family store, when he suddenly disappeared. At 3:00 PM, he returned from the town’s ballpark, sweating and apprehensive, announcing there were three baseball scouts from the New York Giants organization asking to see his father because they want to sign him to play pro ball. His father said, “I am the one to sign you.” An hour later, Alejandro Pompez came to the home to talk.

This was the same Alex Pompez named to the Hall of Fame in 2006. José was on shaky ground here with his father, because he knew that his father wanted him to finish university before thinking of playing professionally. One of José’s friends had prevailed upon him, though, knowing there was a tryout being held, and argued, “Hey, this is a good chance to show them what you can do. I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll go to your place. I’ll pack your bag, and then I’ll meet you someplace else.” José made up an excuse and left the store for the rendezvous. “My dad almost killed me when I came back! (laughs) I told him, ‘Hey, they liked me. They want to sign me….’”

So began the saga of Santiago’s signing. Both Pompez and Pancho Coimbre of the Pirates were interested, but Coimbre deferred to Pompez, just letting it be known that if things didn’t work out, he’d be interested. Pompez offered $25,000 but José’s dad wanted him to finish college first. That would mean waiting three years, not what the youngster wanted to hear. He pleaded with his father. Both scouts agreed on José’s potential, Pompez saying, “He’s got a lot of tools. He can play professional and I’m pretty sure he can get to the big leagues.”

Alejandro asked Pompez, “Well, all right, do we get the money now or he’s going to get the money later? What’s the deal on that?” “Oh no, as soon as he gets to spring training, we’re going to send you the money.” It was worked out and José signed. Then he reports, “I went to spring training. I went through the whole spring training. Never got the money.” His father called. They talked. The Giants said not to worry, and sent him to D ball. He was slated to pitch the opening night game, but stood fast. “I told them, ‘I’m not going to pitch until I get my money.’ They said, ‘You’re going to get it. You’re going to get it.’ My dad called me up and said, ‘I’m going to send you a ticket. You come home.’ So I came home. They tried to get me back, and I said, ‘No.’ They lied to me.” His father was a man of his word, and José and his father were united.

He had a written contract and could have consulted a lawyer, but his father didn’t want to go that route, and José determinedly headed back to school. At that point, Kansas City scout Félix Delgado saw José pitch a 12-strikeout game against a team from the University of Puerto Rico. Delgado called Sr. Santiago, and they talked, with José and his father explaining about the experience they’d had with the Giants. Delgado offered $15,000 –but paid in advance.

Playing later for owner Charley Finley, and well aware of the reputation Finley had, José interjected a memory of the time he tried to help out some fellow players: “To me, he was outstanding. He treated me great.” A humorous story followed. “The only thing bad that I did…at the time, Orlando Pena, Diego Segui, Aurelio Monteagudo, Bert Campaneris, and all those guys…they didn’t know how to speak English at all. I made a big mistake. They talked to me about it. I went to the office to see Mr. Finley about it. First thing he said: ‘Are you a baseball player or are you an agent?’ I said, ‘Wait a minute. I’m just trying to help these guys.’ ‘All right. What do you need?’ ‘They want a raise and….’”

Finley agreed on the spot, and said, “All right, I’m going to give them a raise.” He arranged for a new contract, and as they all got up to leave, Finley said, “José. You stay here.” “What is it, Mr. Finley?” “You know how much I like you and all that, but never…never do that again. Let their own people…they can take care of their own business, even in Spanish, but don’t get involved with this, because this is not your job. You’re here because you want to do a job. So you go out on the field and do the job. I’m glad you did this for those kids. I appreciate that, but this is a business All right. You got what you wanted. Now get the hell out of here.” José laughs, telling the story, adding, “He was tough, but he was a great guy. To me, he was great.”

José started his pro career in 1959 with Olean in the New York-Penn League, with a 6-3 or 5-3 record (accounts differ) and a 3.24 (or 3.34) ERA in 62 innings. The same year, he moved on to Grand Island in the Nebraska State League, winning three and losing six, with a 3.91 ERA. He pitched for Albuquerque in 1960 and on June 13, José threw a 2-0 no-hitter against Hobbs. It was the first no-hitter in the 28 years of the Albuquerque franchise. Just a walk and two errors – all in the sixth inning – prevented the perfect game. With the bases loaded, José struck out the final batter. At the time, The Sporting News made it clear that José “Palillo” Santiago was no relation to the older Puerto Rican pitcher Jose “Patalones” Santiago, pitcher for Cleveland and Kansas City 1954-56.2 With Albuquerque, the young “Palillo” had an excellent 15-6 record with a 3.30 ERA.

In 1961, he pitched for both Visalia and very briefly for Shreveport, leading the California League with 218 strikeouts but also leading in bases and balls, with 130. Back in Albuquerque in 1962, he won a league-leading 16 games against just nine losses. For most of 1963, he played for the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League (12-15, 3.66 ERA), and near the end of the year got his first chance in big-league baseball.

As noted at the start, José broke in for Kansas City with a perfect eighth inning in relief in the September 9, 1963 game at Municipal Stadium against the Yankees. He was pulled for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the eighth but the Athletics pushed a run across and José got the win. He next appeared in a game just two days later, also against the Yankees, pitching the final two innings of a game he entered with the Yankees ahead, 5-1. He let in three runs on three hits, one of them a two-run Joe Pepitone homer. Santiago appeared in two more games in 1963: Boston’s Dick Stuart hit a solo homer off him in a game Orlando Pena started (and lost), and he threw the final two innings of a game lost to the Indians, 7-0. All four appearances were in Kansas City. Santiago ended the year with a record of 1-0, but an ERA of 9.00 in seven innings. He’d yielded four home runs in those seven frames.

In 1964, José started the season with Dallas in the Pacific Coast League but only pitched two innings in one game. After a stretch on the disabled list for half of April and most of May, he returned to the Athletics in early June and appeared in 34 games throwing a total of 83 2/3 innings, including eight starts. Kansas City finished in last place, with a record of 57-105, some 42 games out of first place. Santiago posted a 4.73 ERA, but an unfortunate 0-6 won-loss record. Five of the six losses came in games he’d started, the last one being a 3-2 loss to the White Sox on October 2. In 1965, he started the season with the big league club, but only appeared in four games. The May 2 game against California was his last one of the year, and the last one for the Athletics. He spent most of the year with Vancouver in the Pacific Coast League, and got some innings in, 119 of them, with an excellent 2.19 ERA. The Red Sox took note and purchased him from Kansas City on October 15 for a reported $50,000 in cash. “I enjoyed my time with the A’s,” José told Herb Crehan. “I got along well with Charlie Finley, and I met my wife Edna there. I also got to know Sully [Haywood Sullivan] very well.”3

After a full year with the Red Sox in 1966, he found himself looking up at Kansas City in the standings. The Red Sox finished in ninth place, a half-game ahead of the last-place Yankees, while KC was three games higher up in seventh place. But José got in a full 28 starts and, despite pitching for a ninth-place team, won 12 games with a 3.66 ERA. His record was 12-13, with seven complete games to his credit and 119 strikeouts. “We played very well in the second half of the season, but hardly anybody noticed,” José recalled to author Crehan. José was selected as Red Sox Pitcher of the Year. The Red Sox investment had already paid off nicely.

In 1967, Santiago’s first three appearances came out of the bullpen, allowing just one earned run in four innings, winning one and losing one – both against the Yankees. He then made five starts in a row, again winning one and losing one. After the May 30 start (he was hit for four earned runs in three innings, though the Sox won the game in the end), it was back to the bullpen until August 19 when he started against California. His record was 6-4 at the time. He wasn’t involved in the decision, but pitched again in relief the very next day and earned a win, throwing the final two innings in the game the Red Sox won 9-8, overcoming a 6-0 deficit. For the rest of the regular season, he was used both as a starter and reliever and he won five more games while losing none. He threw a complete-game win against the Orioles on September 22 and Dick Williams gave him the ball to start against the Twins on the next-to-last game of the year on September 30. A loss would take the Red Sox out of the race, but José won a hard-fought game, going seven innings while allowing just two runs, and leaving to a standing ovation from the Fenway faithful. The Red Sox won the game, and won the pennant the next day. As Herb Crehan once wrote in the Red Sox Magazine, “Every Red Sox fan recalls the scene of Jim Lonborg being carried off the field…when his victory clinched at least a tie for the American League pennant. But it was Santiago’s gutsy seven-inning stint on Saturday that set the stage for Lonborg’s triumph.”

Dick Williams named José Santiago as his starting pitcher in the first game of the 1967 World Series. Santiago pitched a solid game, allowing the Cardinals just two runs in seven full innings. It was his misfortune to be paired against Bob Gibson, who allowed but one Red Sox run – a third-inning solo home run by José himself in his first-ever World Series at-bat. His only other major league homer had come off Mickey Lolich in the second inning of the May 14 game against the Tigers, a 13-9 Red Sox win. Lifetime at the plate, he was .173 with six doubles and seven RBIs. In World Series play, he batted .500.

He got another start, in Game Four, but this one was a disaster. Again facing Gibson, who shut out the Sox, José was bombed for four runs on six hits and never made it out of the first inning. José appeared one more time, throwing two innings of perfect relief in Game Seven. But Jim Lonborg had imploded, and the Red Sox were losing 7-1 by the time José had entered the game. The Red Sox lost Game Seven and lost the World Series. José’s record shows 0-2, but Game One against Gibson was a strong effort. José finished the regular season with a 12-4 record and a 3.59 ERA. He forever holds the distinction of being the first Latin pitcher to start the opening game of a World Series. Santiago praised both his teammates and Dick Williams to Herb Crehan: “Williams kept us focused from start to finish. He deserves a lot of credit.”

In 1968, Santiago appeared in just 18 games, every one as a starter. His record was 9-4 with a sterling 2.25 ERA. He was on a roll from the 1967 season, and won his first four decisions, a string of 12 straight wins without a defeat. In his first four games, he gave up a total of just 14 hits. The first game he lost was a hard-luck 1-0 defeat by Mel Stottlemyre and the Yankees on May 11. He lost another 1-0 game on an unearned eight-inning run on May 25 to the Twins, and a 2-1 game on another unearned run on June 18. Dick Williams named Santiago one of his seven pitchers for the 1968 All-Star Game, but he developed tendonitis in his right elbow in early July and did not pitch in the game. He returned for one last game, on July 18 game, but it was his last of the season. He’d only given up one hit and no runs in two innings, but the injury was re-aggravated and he had to turn things over the Gary Bell. He missed the rest of the year.

On June 13, in a nightmare incident, one of José’s pitches hit Paul Schaal and fractured his skull. Schaal was out for weeks, came back for just two more appearances in early August, but did not return to major-league play until 1969. Schaal performed well after his return, but the incident may have shaken Santiago, too. Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote of Santiago weeping at Schaal’s hospital bed and wondered in print in a late 1971 column that Santiago was never the same pitcher afterward, writing “because his elbow – or something – was bothering him.”4

It was one of the rare winters that José did not keep busy playing winter ball as well. Unfortunately, even time off over the winter wasn’t sufficient and late in 1969 spring training, Santiago reinjured his elbow, tearing a ligament in his right elbow after throwing just two warmup pitches. A few weeks later, on April 22, he had elbow surgery in Boston. Doctors said it was 50/50 whether he could ever pitch again, but if he could, it would probably not be until 1970.

In fact, the surgery and rehab went quite well, and he rejoined the Red Sox in August, less than four months later. In his first appearance since July 18, 1968, Santiago threw a scoreless eighth and final inning in relief on August 24. Five days later, he did the same: a scoreless ninth. Appearing from time to time, he got in 10 games, pitching just 7 2/3 innings, but with a very good 3.52 ERA.

Before spring training opened in 1970, he said that he could no longer effectively throw his money pitch – the slider. He worked at it during the exhibition season, but he wasn’t ready for big league action and so started the season with Louisville in the International League. He pitched in 19 games for Louisville (7-4, 3.62 ERA).

He got the call to Boston at the end of May. His first appearance, though, was as a pinch-hitter in the May 29 game at Fenway Park against the White Sox. Chicago was winning 3-1, and the Red Sox had a man on first with one out. Santiago was put in to pinch-hit for Jim Lonborg and singled sharply to left field. Mike Andrews drew a walk to load the bases and Billy Conigliaro singled to drive in two, José scoring the tying run. Carl Yastrzemski walked, and Jerry Moses won it with a walkoff single. His first stint on the mound came on May 31, giving up three runs in two innings as one of six Red Sox pitchers mauled by Chicago batters, in a 22-13 slugfest. Apart from the pinch-hit cameo, José appeared in eight games for the 1970 Red Sox (11 1/3 innings, 0-2, with a 10.32 ERA; they were his last games in the major leagues.)

Louisville beckoned, and Santiago gave another shot in 1971, throwing 128 innings and pitching well enough (7-6, 4.08 ERA) but those were his last years in American baseball. The Red Sox offered him a job as a coach in the organization, but José declined. He harbors good memories, though, telling Herb Crehan, “One thing I will always remember is that the Red Sox treated me with as much respect when I was a sore-armed pitcher as when I was an All-Star. Dick O’Connell, who was the general manager at the time, was wonderful to me. And the Yawkeys were very special people.”

He was out of American baseball for the years 1972 through 1975, playing most winters in Puerto Rican teams. He told author Herb Crehan, “I still knew how to pitch, but I knew I wasn’t at big league form. Some of my teammates would say, ‘You could probably make a comeback’ but I knew better.” In 1976, José pitched for Union Laguna in the Mexican League, appearing in 43 games, winning 13 against 6 losses, with a 3.35 ERA.

Since his final season in Mexico, José has resided fulltime in Puerto Rico. In 1980, he founded the Academia Beisbol Palillo Santiago, and the school served as many as 300 boys a year between ages 7 and 17. He had the school for 10 or 15 years, but as more kids chose to play video games than baseball, the number of students began to dry up. José remains devoted to trying to foster youth baseball, however. For around 25 years, he has helped Little League baseball, in which he strongly believes. For a good long time, he was president of Little League for the whole San Juan area. “Half of my time, I dedicated to the Little League program. All the programs are great, but Little League is the one that I really enjoy, because if you’re crippled or any kind of problems that you have, you can play Little League. They’ll let you play. Not the other leagues. So that’s why I’m there. I love Little League so much. And I still help them out. As soon as I have time, I’ll do anything for the Little League. And for the kids.”

Santiago also managed the Puerto Rican team for some time, and was pitching coach as well. During the 1980’s, he served as Press and Publications Officer for the Sports and Recreation Department of the Government of Puerto Rico. In fact, after leaving major league baseball, José has been very energetic with an almost bewildering array of activity. Among other things he has been:

- Voice of the San Juan Senators for five years

- General Manager and Voice of the Santurce Crabbers for almost 10 years, named Narrator of the Year three times

- President of Little League baseball for 20 years

- Manager of the Puerto Rican national team

- Manager of a number of AA Amateur Baseball League teams, including Coamo, Juana Díaz, Río Piedras, Juncos, San Sebastian, and Río Grande.

- Pitching Coach for the Chicago Cubs Daytona Beach Class-A team in 2000

- Voice of the Carolina Giants in the Puerto Rico Professional Baseball League team 2004-2006.

As Crehan wrote these authors, “José is to Winter Baseball in Puerto Rico what Johnny Pesky is to the Red Sox.”

Today, José Santiago lives in Carolina, Puerto Rico, with his wife Edna, whom he met while playing for Kansas City. They have been married for more than 45 years and raised four boys: Alex, Arnold, Albert, and Anthony. Three of the boys played baseball to one extent or another. Alex was offered a signing bonus by the Phillies, but he turned it down and runs a business working with computers. Arnold was drafted by the Cleveland Indians, but never had enough playing time to show what he might have been capable of achieving. A third son got into umpiring for a while, but left to raise horses and do other work.

José keeps busy with his work broadcasting for Carolina. He also enjoys writing and reciting poems about love and family, perhaps reflecting the “City of Poets” where he was raised.

Last revised: May 1, 2017

An updated version of this biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It first appeared in “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium on the Field” (Rounder Books, 2007), edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers.

Notes

1 Author interviews with José Santiago by Edwin Fernandez on January 21, 2006 and Bill Nowlin on March 15, 2006. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from Santiago are from these interviews.

2 “Dukes’ José Santiago Hurls No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1960: 38.

3 Herb Crehan. “The Impossible Dream Team Revisited / Where Are They Now: José Santiago,”

Red Sox Magazine, 1997. All quotations attributed to Crehan come from this source.

4

# Jim Murray. “A Royal Favorite,” Los Angeles Times, September 28, 1971: E1.

Full Name

José Rafael Santiago Alfonso

Born

August 15, 1940 at Juana Díaz, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.