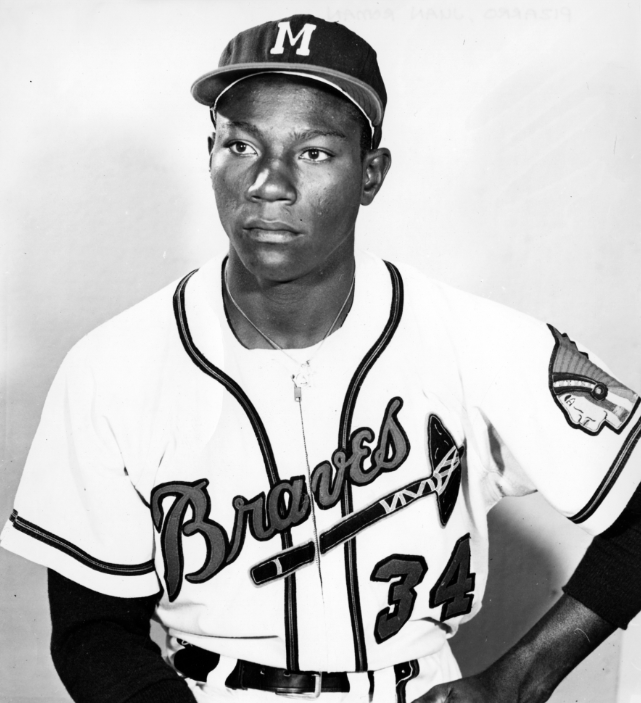

Juan Pizarro

Juan Pizarro was a talented, durable Puerto Rican pitcher. The lefty pitched in all or part of 18 major-league seasons, starting as a rookie with the 1957 Milwaukee Braves. The Braves rushed him to the big club after one eye-opening season in Class A, yet their very deep pitching staff limited Pizarro’s opportunities. He did not come into his own as a big leaguer until 1961, after he was traded to the Chicago White Sox. His best record was 19-9 in 1964 – but he never had another season with double-digit wins in the majors. After 1965, Pizarro was primarily a reliever at the top level.

Juan Pizarro was a talented, durable Puerto Rican pitcher. The lefty pitched in all or part of 18 major-league seasons, starting as a rookie with the 1957 Milwaukee Braves. The Braves rushed him to the big club after one eye-opening season in Class A, yet their very deep pitching staff limited Pizarro’s opportunities. He did not come into his own as a big leaguer until 1961, after he was traded to the Chicago White Sox. His best record was 19-9 in 1964 – but he never had another season with double-digit wins in the majors. After 1965, Pizarro was primarily a reliever at the top level.

Still, looking at his entire professional career, “Terín” won more than 400 ballgames. His regular-season count is 392: 197 in the US (131 in the majors and 66 in the minors), plus 38 more in Mexico in his late 30s and 157 while playing winter ball in his homeland.1 Pizarro was one of the most successful pitchers in the history of the Puerto Rican Winter League (PRWL). His career there spanned 22 seasons, from 1955-56 to 1976-77. As of 2012, El Látigo de Ébano – The Ebony Whip – ranked second in wins in the league’s history. It came as no surprise that when the Puerto Rican Baseball Hall of Fame inducted its first 10 members in 1991, Terín Pizarro was one of them.

Pizarro accomplished as much as he did despite his great love of eating, drinking, gambling, and carousing. In a vivid 1982 interview with author Edward Kiersh for the book Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, he came across as a boricua Bo Belinsky. “Yeah, I love to cel-e-brate,” he said. “I only remember the parties, the women, the hot times.”2

Juan Ramón Pizarro Córdova was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, on February 7, 1937. His father, Zenón Pizarro, was listed in the 1940 census as a construction worker – but Zenón mainly occupied himself as a trainer/gambler in cockfighting (a pastime that remains popular – and legal – in Puerto Rico).3 Juan’s mother, Ramona Córdova, had three daughters before him. They were named Celestina, Ramona, and Alejandrina. In his childhood, he got the nickname that stuck with him for life: Terín. The neighborhood kids likened him to the main character of the comic strip “Terry and the Pirates.”4

From the age of 13, Pizarro served as a batboy for his hometown team in the PRWL, the Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers). Strange to relate, he had not grown up playing baseball. As he explained to Ed Kiersh, though, “I was so busy being bad, I didn’t start playing ball until I was fourteen.”5

It was only after he joined some boys in the neighborhood for a game of piedritas – throwing rocks at bottles – that Pizarro found out about his own talent. “I had never done much throwing,” he said in May 1956, “even though I had been batboy for Santurce for three years. Some of the boys could throw pretty fast, but I discovered I could throw harder than any of them. And I hit more bottles too.” He then began to play amateur league baseball as a high-school junior and proceeded to win 14 games, followed by 19 more as a senior.6 The team was run by a man named Harry Rexach, a big Santurce fan and friend of the Crabbers’ longtime owner, Pedrín Zorrilla.7

Pizarro was not big for a pitcher, especially by today’s standards. He grew to just 5-feet-11 and weighed only 170 pounds as a young man. Eventually he weighed as much as 190 to 200 – or at least that was the figure in print. “I came to the end of the road a lot quicker because I loved to eat,” he freely admitted to Ed Kiersh, patting his stomach and smiling.8 He had a very live arm, though he did not rely on his fastball alone. His repertoire also included a curveball and – for a time – a screwball, learned from fellow Puerto Rican Rubén Gómez. Mastering his control was a challenge for him in the majors.

Pizarro pitched his first five games as a pro with Santurce in the winter of 1955-56. Pedrín Zorrilla signed him to his first contract. Terín played just 2½ of his 22 winters at home in a non-Crabbers uniform. He was so loyal to winter ball and his team that he turned down an offer for $5,000 from the White Sox not to play following the 1964 season. After the pitcher retired in 1977, the man who then owned the club, Hiram Cuevas, “made sure Pizarro was rewarded with a 20-year coaching contract.”9

On February 13, 1956, Pizarro signed with Milwaukee. The scout responsible was a fellow Puerto Rican, Luis Olmo. Olmo had finished his big-league career with the Boston Braves in June 1951 and became a full-time scout for them at the end of 1953. Pizarro’s first manager in the US, Ben Geraghty, endorsed the young hurler too. Geraghty was also the skipper of another Puerto Rican team, the Caguas Criollos. He said, “When Milwaukee called me up to ask what I thought of Pizarro, I told them he definitely had a major-league arm and could throw harder than anyone in the Milwaukee organization.”10

According to Pedrín Zorrilla, Santurce received $34,000 from the sale – $2,000 of which went to Terín. His salary for his first year in the US was also to be $2,000 – but that was a raise from the $35 per week that he’d been earning in a San Juan factory.11 The 19-year-old reported to Jacksonville in the South Atlantic League (Class A). The young man could not speak English then; when Geraghty needed to confer with him on the mound, he needed help from veteran Cuban pitcher Adrián Zabala.

Right from the start, Pizarro was dazzling. In his debut he struck out 14 in six innings before tiring and taking the loss. In his next start, he whiffed 21 in 12 innings.12 He got 20 Ks against Macon on June 27.13 For the season, he was 23-6 with a 1.77 ERA. In 274 innings pitched, the Sally League’s MVP struck out 318, including at least ten men in 15 of his 31 starts. Pizarro walked 149, which was forgivable in a young flamethrower pitching at that level. That August, Ben Geraghty said, “I’d say there are faster pitchers, even in this league. But his ball really moves. Too many good hitters in this league are swinging and missing. His ball is alive and that is what’s going to make him a great big leaguer.”14

John Quinn, general manager of the big club, “did not rule out the possibility” that Pizarro might get a call-up to Milwaukee.15 That didn’t happen, but another indication of the prospect’s promise came from the Sally League’s president, Hall of Famer Bill Terry, who raved, “He could be as great as [Warren] Spahn.”16

During the winter of 1956-57, Pedrín Zorrilla sold the Crabbers. The new owner, Ramón Cuevas, in turn sold the contracts of Pizarro, Roberto Clemente, and second baseman Ronnie Samford to Caguas.17 Shortly after the deal, Pizarro suffered two broken ribs in an auto accident, and the Braves ordered him to quit for the remainder of the PRWL season.18 He had shown further promise, however, throwing two shutouts while still with Santurce. The level of competition was generally regarded as just a small step down from the majors.

In January 1957 Milwaukee manager Fred Haney talked about the “southpaw phenom.” He said, “The only thing I question is [Pizarro’s] bases-on-balls record. Maybe the kid needs another year in the minors to work on his control. Those walks will send a manager to an early grave.”19 During spring training in Florida, Pizarro said of his control, “It’s okay.” Speaking from the Bradenton rooming house where the Braves of African descent had to reside, the 20-year-old was quite confident. When asked what he had to improve upon to make good in the major leagues, he said simply, “Nothing.”20

Indeed, Pizarro started the 1957 season with the big club.21 He did not get a chance in a regular-season game, however, until May 4. At Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, the rookie lost a 1-0 duel to Vernon Law. “Even then it took a couple of ‘seeing eye’ singles in the seventh inning to beat him.”22 In his next outing, at St. Louis on May 10, the Braves gave Pizarro a big early lead and he went all the way to win, 10-5. Terín helped himself by going 2-for-4 and scoring three runs, including a solo homer off Sam “Toothpick” Jones. He was a respectable batter for a pitcher, hitting .202 lifetime in the majors with eight homers (including three in 1964).

Pizarro was in the starting rotation for six turns from late May through mid-June, but after that, the Braves used him sporadically. They sent him down to Triple-A Wichita “for more experience” on July 3; there he was 4-0 in five starts, though with a fairly high ERA of 4.25. After Pizarro returned in late July, The Sporting News wrote, “the young Puerto Rican was counted upon for important assistance as a reliever and spot starter down the stretch.”23

Yet as it developed, Fred Haney called on him just ten more times with only one start. His most impressive performance came at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field on August 31. The Braves gave Lew Burdette a 5-0 lead in the first inning, but Burdette retired just one batter before Haney gave him the hook. Pizarro went the rest of the way for the win, striking out nine and giving up just two runs. He finished his rookie year at 5-6 with a 4.62 ERA in 24 games (10 starts). Control was an issue; he walked 51 men in 99⅓ innings.

Pizarro got into one game during the 1957 World Series. In Game Three at County Stadium, after the Yankees knocked Bob Buhl out of the box in the first inning, Terín pitched 1⅔ innings. He gave way to Gene Conley in the third inning after giving up two more runs to New York in the 12-3 loss.

That December Milwaukee beat columnist Bob Wolf wrote, “Juan Pizarro … was a disappointment, although in his case the problem seemed to be solely one of inexperience. Had he been able to spend the entire campaign at Wichita, pitching every fourth or fifth day instead of rusting away in the Braves’ bull pen, he might have been ready for stardom in 1958. But because [Taylor] Phillips failed and nobody else was available to take up the slack, Pizarro had to be kept for all but a month of the season.”24 As Ed Kiersh also noted, though, “Haney … wondered so much about J.P.’s whereabouts he had to send out groups of players, or even the police, to scour the bars for the missing rookie.”25

Meanwhile, in the winter of 1957-58, Pizarro’s performance with Caguas was simply spectacular. He became the second of four pitchers in PRWL history to win the Triple Crown of pitching.26 In 19 games, he was 14-5 with a 1.32 ERA. He struck out 183 and allowed just 94 hits in 170⅓ innings. He broke the league’s single-season record with nine shutouts. In addition, on November 21, he broke the league record for strikeouts in a single game – held by Satchel Paige and Bob Turley – with 19 against Ponce.27 Nine days later he threw a no-hit, no-run game against Mayagüez. He also had a one-hitter and a two-hitter that season. He richly deserved – and won – league MVP honors.

Pizarro had many other excellent seasons at home, and only a few that could be described as so-so or bad. This, however, may have been the best stretch of his entire pro career. It continued in the Caribbean Series. Caguas represented Puerto Rico as PRWL champion, and on February 8, 1958, Pizarro fired 17 strikeouts in an 8-0, two-hit win over Carta Vieja of Panama, shattering the Caribbean Series record.28 Cuba became tournament champion, though – and a big turning point came two days later, with Pizarro on as a fireman in the ninth inning. The bases were loaded with nobody out, and the tying run would have scored anyway on a long fly to right field, but when an umpire ruled that the ball had been dropped, the irate crowd at San Juan’s old Sixto Escobar Stadium started “a small-scale riot.” The game was suspended and completed the following night.29

Yet despite his brilliance, Pizarro had a disappointing spring camp in 1958.30 Perhaps he was tired – he’d pitched around 200 innings that winter and had weakened late in another Caribbean Series start. At any rate, there was no room for him on Milwaukee’s staff. He went back to Wichita to start the season. Though his record was only 9-10 in 23 games, his ERA was 2.84 and he fanned 158 in 165 innings. The Braves recalled Pizarro in late July, and he responded with three straight complete games, winning two and losing one. Overall with Milwaukee that season, Pizarro was 6-4 with a 2.70 ERA in 16 games (10 starts).

Pizarro’s good work in the second half won notice. In early September United Press International wrote, “Juan Pizarro, little more than a spectator in the 1957 World Series, is ready to play a major role for the Milwaukee Braves when they try to make it two in a row over the New York Yankees this year.”31 Again, though, he got to make just one relief appearance in the Series; in Game Five at Yankee Stadium, he was dropped into hot water. New York was ahead 1-0 going into the bottom of the sixth, but Braves starter Lew Burdette weakened, allowing two runs and leaving the bases loaded for Pizarro. By the time the inning was over, the Yankees were up 7-0, and that was where it ended.

Despite some gems, Pizarro never blossomed in Milwaukee. In 1959 he was 6-2, 3.77 in 29 games, interrupted by another stretch at Triple A in June. During his time at Louisville, he pitched a no-hitter against Charleston at home on June 16. Four days later, this time at Charleston, he was four outs away from back-to-back no-hitters but had to settle for a two-hit shutout.32

Before the 1959-60 season in Puerto Rico, Pizarro (plus $10,000) came back to Santurce in return for Julio Navarro and José Pagán.33 In 1960 he spent the full year with Milwaukee for the first time. The Braves’ new manager, Charlie Dressen – who encouraged Pizarro to discard his screwball – compared him to Sandy Koufax (as well as Mike McCormick and Dick Ellsworth).34 Even so, he was just 6-7, 4.55.

On December 15, 1960, the Braves traded Pizarro and pitcher Joey Jay to the Cincinnati Reds for veteran shortstop Roy McMillan, a top-notch glove man, plus a player to be named later. As part of a three-way deal, Cincinnati moved Pizarro along with pitcher Cal McLish to the Chicago White Sox for third baseman Gene Freese. White Sox president Bill Veeck said, “In the case of Pizarro, who supposedly lacks the drive and aggressiveness to win, if anyone can put a fire under him it is [manager Al] Lopez.”35 This appears to be another example of a stereotype attached to Latino players in those days.

Braves catcher Del Crandall, speaking to author Larry Moffi, gave another indication of why Milwaukee gave up on the talented young Puerto Rican. “With Juan Pizarro, I think in his case his potential was that he could throw the ball at ninety-five miles per hour. Well, that’s not necessarily potential, that’s somebody with a good fastball. … It was just, throw the ball hard and then turn that little screwball over at times. But I don’t think that he was consistent in getting the pitches where he needed to get them in times of trouble.”36

Looking back, Pizarro’s great teammate Henry Aaron wrote, “I’ve always felt that we would have won some more championships if we had hung onto Pizarro and Jay. We needed young pitchers to take over for Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl, and we never came up with them. … I’m not sure I ever saw a pitcher with more ability than Pizarro had when he came to us out of Puerto Rico at the age of nineteen.”37

Aaron’s book went on to quote another Puerto Rican Brave, Felix Mantilla, who was also of African descent. “I don’t think our managers and front office ever understood Pizarro. He was always in shape and ready to pitch, but he was moody. Managers would say things to him about being moody and it would just make him angry.” Mantilla then went on to talk at length about the “unwritten rule” in those days against having five black players on the field at the same time, which cost both him and Pizarro playing time.38 Pizarro himself told Ed Kiersh, “Because I was Latin they thought I was a troublemaker.”39

Pizarro’s breakout year in the majors came at last in 1961 – though he did not start or win a game for Chicago until June 10. During that season, he was 14-7 with a 3.05 ERA. His walks were down to 4.1 per 9 innings pitched, and his K/9 ratio was a career-high 8.7, which also led the AL that year. Al Lopez said, “When Pizarro first joined the club in 1961 he was fooling around with a screwball. Here was a young pitcher with control trouble, so I told him to concentrate on finding the plate with his fastball and curve and forget about the screwball. He had enough stuff without it.”40

“The White Sox didn’t give up on me, they didn’t punish me, and I pitched my ass off for them,” Pizarro told Kiersh.41 The bon vivant backslid in 1962, though – “late-night carousing and skipping practices led to a 12-14 mark, numerous fines, and Lopez’s turning gray.”42 Still, he enjoyed another career highlight that winter. Mayagüez, the PRWL champion in 1962-63, signed Terín as a reinforcement for the Inter-American Series. On February 8, 1963, he threw a no-hitter against the Venezuelan champs, Valencia – the only no-no in the history of that tournament.43

Pizarro followed with his two best seasons in the majors. He was an American League All-Star in both 1963 (16-8, 2.39) and 1964 (19-9, 2.56). His career-high win total in ’64 broke the big-league single-season mark for pitchers born in Puerto Rico.44 He was also runner-up to teammate Gary Peters among the AL’s ERA leaders that year. Despite an anemic offense, the strong pitching of the White Sox led them to challenge the Yankees strongly – they finished just one game back in second place.

Pizarro was able to make only 18 starts for the White Sox in 1965, however; a salary holdout contributed to a sore arm, and he took the mound just seven times through June 23. He didn’t get past five innings in any game. Eventually, examination revealed a torn triceps tendon in his pitching shoulder.45 Pizarro made it back by late July and pitched much better in the season’s second half. On August 11 – relying heavily on breaking balls46 – he threw the first of his two one-hitters in the majors, shutting out Washington at Comiskey Park. He wound up at 6-3, 3.43 for the season.

From 1966 onward, Pizarro made just 58 starts in his remaining nine major-league seasons, against 182 relief appearances. He bounced around with six different teams: Pittsburgh, Boston, Cleveland, Oakland, the Chicago Cubs, and Houston. He also returned to the minors for parts of 1970 – which included a 9-0 run for the Hawaii Islanders, then a California Angels farm club – 1971, and 1973.

The 1971 season with the Cubs had noteworthy performances, though. Chicago called Pizarro up from Triple-A Tacoma in July and used him mainly as a starter (14 times in 16 outings). On August 1 at New York’s Shea Stadium, Pizarro went all the way and beat the Mets’ ace, Tom Seaver, 3-2. Four days later, he threw his other big-league one-hitter, blanking San Diego at Wrigley Field. On September 16, again at Shea, once more he bested Seaver, who was having his greatest season ever. The score was 1-0 – and Juan’s solo homer in the eighth inning accounted for the game’s only run. Only nine pitchers have achieved this feat since 1900, and just two since Pizarro: Bob Welch (1983) and Noah Syndergaard (2019).

Pizarro didn’t do much for the Cubs in 1972. The following year – “admittedly ‘fat, lazy, and not giving a s*** at this point’”47 – he appeared just twice with Chicago before his contract was sold to Houston. After the Astros released Pizarro in April 1974, he went to Mexico, joining the Córdoba Cafeteros. In his first season south of the border, Terín was 13-6 with a brilliant ERA of 1.57, best in the league. He had 15 complete games in his 20 starts, with nine shutouts, including five in a row at one point. Both figures tied Mexican League records. At first it was thought that he had set a new mark with six straight blankings, but the league statistician pointed out that he had given up a run in relief.48

As a result of Pizarro’s success, the Pirates signed him that August 19. Three days previously, general manager Joe Brown had said, “I might make a move in the next few days that might make you think I’m out of my mind.” But Pittsburgh was in third place in the National League East at the time, and it was a low-cost maneuver.49 Over the next several weeks, Pizarro pitched seven times. Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh made him the starter for the last two of those appearances, and he got his final big-league win on September 26. At Shea Stadium, with a big early lead, he went eight innings, coming out only after the Mets scored two unearned runs in the eighth. Fellow Puerto Rican lefty Ramón Hernández closed out the 11-5 victory. Pizarro also got two hits that day.

Pittsburgh went on to win the NL East in 1974, and Pizarro remained on the postseason roster. His last appearance in the majors came in Game Four of the NLCS on October 9; he got the last two outs as the Dodgers drubbed the Pirates 12-1 to advance to the World Series.

Pizarro was in spring training with the Pirates in 1975 as a nonroster player but did not make the team. Returning to Mexico, he continued to excel for Córdoba in 1975 (14-7, 1.98) and 1976 (11-8, 2.64). He finished his Mexican career with a record of 38-21, 2.04, with 42 complete games and 17 shutouts in his 63 starts.

All along, Pizarro had been playing winter ball at home. He was a member of six PRWL champion teams and appeared in five Caribbean Series tournaments. Caguas won in his Triple Crown year, 1957-58, and added him as a reinforcement for the last edition of the tourney’s first phase in 1960. Pizarro won five more PRWL titles with Santurce (1961-62, 1964-65, 1966-67, 1970-71, and 1972-73). The Caribbean Series returned from hiatus in 1970, and Santurce represented Puerto Rico in 1971 and 1973. In between, Pizarro played in the Inter-American Series each year from 1961 through 1964.

Pizarro also reinforced the Bayamón Vaqueros for the 1976 Caribbean Series. He rewarded manager José Pagán’s surprise choice by throwing a three-hit shutout against Venezuela on his 39th birthday. “I used my experience in winning that game for Puerto Rico,” he said. “It was nice to finish my Caribbean Series career as a winner.”50

During the winter of 1976-77, Pizarro pitched his last 11 games as a pro for Santurce. His final record in Puerto Rico was 157-110, with a superb 2.51 ERA. Only Rubén Gómez had more wins (174, and he needed 29 seasons to do it). Pizarro pitched 2,403 innings, again second behind Gómez, and allowed just 1,980 hits. He is the PRWL’s all-time leader in strikeouts (1,804) and shutouts (46), marks that will almost certainly never be challenged.

In addition to coaching the Crabbers off and on, Pizarro stayed involved with baseball in other ways. As of the early 1980s, he was working for Santurce’s Parque Central as an instructor, with the additional goal of keeping kids out of trouble.51 As late as 1997, he was back in the US, coaching with the Rockford Cubbies of the Midwest League (Class A). The manager was one of his contemporaries in the majors, Rubén Amaro, Sr. “He was very professional for me as well as our young pitchers,” said Amaro, “and I know many of those young players were touched by his experience.”52

In January 2007, Terín told columnist María Judith Caraballo that he was totally retired and enjoying a peaceful life at home in the same section of Santurce, Villa Palmeras, where he grew up. He mentioned a wife, though not by name, in the Kiersh interview. Although information on children is also lacking, Pizarro was a father figure to one of his nephews, Charles West. After not having been to any ballpark for three years, he was at Game Six of the PRWL finals between the Arecibo Lobos and Gigantes de Carolina. Pizarro told Caraballo stories of his playing days and encouraged young Puerto Rican ballplayers to “work hard, run a lot, and practice enough.”53

After an 18-month battle with prostate cancer that metastasized, Pizarro died at the age of 84 on February 18, 2021. Among the memorials he received, one was especially fitting. Jorge Colón Delgado, historian of Puerto Rican baseball, observed simply this: “Juan Pizarro is the best Puerto Rican pitcher of all time.”

This biography was originally published in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. It is also included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

It was most recently updated on February 23, 2021.

Sources

In addition to the sources in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, ancestry.com (1940 census records), paperofrecord.com (various small items from The Sporting News), checkoutmycards.com (information from Pizarro’s baseball cards), and

Antero Núñez, José, Series del Caribe (Caracas, Venezuela: Impresos Urbina, C.A., 1987).

Crescioni Benítez, José A., El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, ed., Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 11th edition, 2011).

Notes

1 Postseason play – in the minors, Puerto Rico, and international tournaments – got him over 400.

2 Edward Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio? (New York: Bantam Books, 1983), 136.

3 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 133.

4 “Puerto Rican Pitcher Gets Sally Loop Praise,” United Press International, August 7, 1956.

5 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 132.

6 Joe Livingston, “Ex-Batboy Pizarro Finds Sally Hitters Soft Touch,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1956: 34.

7 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999), 76.

8 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 135.

9 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 100.

10 Joe Livingston, “18-Year-Old Lefty Fans 14 in Six Innings in Sally Debut,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1958: 32.

11 The Sporting News, February 22, 1956: 28; “Puerto Rican Pitcher Gets Sally Loop Praise.”

12 Livingston, “Ex-Batboy Pizarro Finds Sally Hitters Soft Touch.”

13 “Pizarro Cools Off Slightly in Red Hot Strikeout Pace,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1956: 41.

14 “Puerto Rican Pitcher Gets Sally Loop Praise.”

15 “296 Strikeouts for Pizarro,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1956: 34.

16 Lou Chapman, “‘Pizarro Could Be as Great as Spahn,’ Says Bill Terry,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1956: 8.

17 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 84.

18 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “Pizarro, Injured in Auto Crash, Quits Winter Ball,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 21.

19 Frank Finch, “Pilot Explains His Promise to ‘Get Tough,’” The Sporting News, January 23, 1957: 4.

20 Bob Wolf, “Phenom Pizarro Sure He’ll Make Grad as Brave,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1957: 17.

21 Bob Wolf,” Kid Pizarro Pitches Way Onto Braves’ Bulging Staff,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1957: 9.

22 Bob Wolf, “Braves, Rich in Hill Talent, Put Two More on Display,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1957: 11.

23 Bob Wolf, “Conley’s Comeback Like Oxygen Whiff to Crippled Braves,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1957: 10.

24 Bob Wolf, “Pitcher-Wealthy Braves Still Seek Bull-Pen Bracer,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1957: 20.

25 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 133.

26 The others were Sam Jones (1954-55), Wayne Simpson (1969-70), and Edwin Núñez (1981-82).

27 Pat Dobson later broke this record on December 10, 1967, when he struck out 21.

28 Pito Alvarez de la Vega, “Latin Winter Crown Again Won by Cuba,” The Sporting News, February 19, 1958: 30.

29 “Latin Tempers Explode,” “Ump’s Ruling Provokes Fan Riot; Series Game Halted,” The Sporting News, February 19, 1958: 30.

30 Bob Wolf, “Braves Find More Pitching Riches in Depth of Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1958: 18.

31 “Pizarro Seen Yank-Beater,” United Press International, September 5, 1957.

32 “Hit in Eighth Halts Pizarro Bid for Second Gem in Row,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1959: 27.

33 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 84.

34 Bob Wolf, “Pizarro Takes Kinks Out of Braves’ Staff by Junking Scroogie,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1960: 15.

35 Edgar Munzel, “Senor to Try Magic on Pizarro, McLish,” The Sporting News, December 28, 1960: 15.

36 Larry Moffi, This Side of Cooperstown (Ames, Iowa: Firehouse Books, 1996), 125.

37 Hank Aaron with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007.)

38 Aaron, I Had a Hammer.

39 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 133.

40 Bill Wise, ed., 1965 Official Baseball Almanac (Greenwich, Connecticut: Fawcett, 1964).

41 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 135.

42 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 132.

43 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 93.

44 Hiram Bithorn – the first Puerto Rican in the majors – had won 18 for the Chicago Cubs in 1943. Ed Figueroa broke this record in 1978 when he won 20 for the New York Yankees. Javier Vázquez surpassed Pizarro for most career big-league wins by a Puerto Rican native in 2009. Note also that “Nuyorican” John Candelaria won 20 games in 1977 and 177 in his career.

45 Edgar Munzel, “Injury Jinx Hits Sox on Double – Juan and Ward,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1965: 3.

46 Jerome Holtzman, “Juan Uses His Curve Ball in Twirling a One-Hitter,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1965: 17.

47 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 135.

48 “Pizarro Streak Ends,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1974: 42. Gary Ryerson broke the record for total in a season with 10 in 1976. That mark has since been matched twice.

49 Charley Feeney, “Pizarro Back for Another Whirl on Bucco Hill,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1974: 7, 28.

50 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 129.

51 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio?, 136.

52 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, December 29, 2012.

53 María Judith Caraballo, “Juan Terin Pizarro La Gloria del Béisbol Puertorriqueño,” 1-800-Béisbol website (http://www.1800beisbol.com/baseball/deportes/latinos/juan_terin_pizarro_la_gloria_del_beisbol_puertorriqueno/), unknown date, 2007.

Full Name

Juan Ramón Pizarro Córdova

Born

February 7, 1937 at Santurce, (P.R.)

Died

February 18, 2021 at Carolina, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.