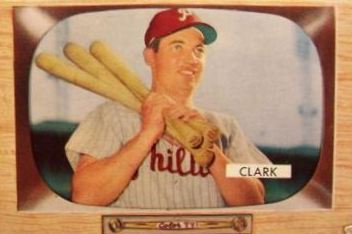

Mel Clark

On the back of his 1955 Bowman baseball card, Mel Clark urges youngsters to have a glove, bat and ball at hand so they can be ready to play when the opportunity presents itself. When that opportunity arose for the war veteran from the sandlots of West Virginia, he seized it with a vengeance.

On the back of his 1955 Bowman baseball card, Mel Clark urges youngsters to have a glove, bat and ball at hand so they can be ready to play when the opportunity presents itself. When that opportunity arose for the war veteran from the sandlots of West Virginia, he seized it with a vengeance.

Melvin Earl Clark was born July 7, 1926, in Letart in Mason County, West Virginia, the first of eight children born to Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Clark. Growing up in the Broad Run area of the county along the Ohio River, the boy known as Earl jumped at every opportunity to play baseball in the sandlots or alone on the family farm. If he couldn’t find a pick-up game, he would spend his idle time honing his skills by doing such things as simple as throwing a ball against a wall.

Clark predicted to one of his school teachers that he would grow up to become a Major League ballplayer, but that prediction looked more pie-in-the-sky as he stood only 5 feet, 6 inches tall and weighed but 130 pounds upon his graduation from Wahama High School. Baseball didn’t arrive at the little school until his senior year in 1942, and then it was only an eight-game season. Most of those games were against Point Pleasant, the bigger school in the county. Wahama fared well against its competition, and its inaugural teams featured two other players who would eventually sign professional contracts — infielder Junie Gibbs and catcher Luther Tucker.

Clark enlisted in the United States Navy in 1943 and was assigned to LSD No. 2, the Bell Grove. His craft carried tanks to aid in South Pacific beach landings at the Gilbert Islands, the Marianas, Saipan, Tinian, Iwo Jima, New Guinea and the Philippines. Fighting to gain control of the Pacific Theater took up most of his time in the Navy, but Clark did find time to play one baseball game during his 33 months in the service. His ship took on the crew of another while both were briefly docked in Pearl Harbor. During his time in the Navy, he grew to 6 feet tall and filled out to 180 pounds.

Discharged from the Navy on February 6, 1946, Clark put his GI benefits to immediate use, enrolling at Ohio University just two days later. He decided to try out for the college baseball team, surviving until the team was trimmed from 30 players down to 25. A couple of weeks later, the coach of the team asked Clark to stop by his office.

“He told me most of the players believed it was a mistake to cut me, and he invited me to come back out for the team,” Clark said. “I told him that I appreciated that, but I would concentrate on my studies and see what happened next year.”

Clark, still known as Earl, played third base for the Hartford (West Virginia) Tigers in the highly competitive Ohio Valley Association during the summer of 1946. His time away from the diamond had not rusted his skills as Clark led the Tigers to the title, breaking the league home run record along the way. A two-homer game on August 25, 1946, in a 16-2 victory over Portland, Ohio, pushed him past the mark held the past eight years by Mason County native and former International League standout Herman Layne. Clark’s .445 batting average and nine homers in just 14 games led the loop. Clark turned down offers from the Phillies, Cardinals and Pirates so that he could return to Athens to continue his studies at Ohio University. “There were two or three good teams in the league,” Clark recalled, adding that Gibbs and Tucker both played on the Tigers, as did Vernon Grimstead, who also played professionally later on. “We had a team I thought was at least Class A caliber.

“One game I recall went into the 15th inning, and I was the leadoff hitter in the bottom of the inning. I looked back at their catcher, and I said, ‘I’m tired, and I’m going to end this game right now.’ I never will forget that. He just looked up at me. I hit a ball that went over the light towers in left field for a home run. When I came around third base, that catcher was right there. He put his arms around me and stopped me. He said, ‘You’re not going to score. I’m holding you right here.’ I told him I was going to end the game.

“The next morning about 7 o’clock, my phone rings,” he continued. “There was a gentleman named Swackhammer who had a dairy farm in Hartford. He said, ‘Mel, well they called me Earl back then, do you want that baseball you hit last night? I found it up here in my barn in Hartford (which was about 3 or 4 miles from the ball field).’ I told him to clean it up a bit if it landed in the barnyard.”’

The Ohio University coach in 1947 kept Clark as a sophomore, and Clark led the team with eight doubles and seven triples. His .313 batting average was the second highest among the regular starters. His play at the collegiate level landed him a summer spot on the Parkersburg (West Virginia) Scotties, a top-flight amateur team that sought out the best competition in West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

His time on the Scotties was brief, but eventful. Clark hit .571 before departing on July 21, 1947, to begin his professional career. He was honored with an “Earl Clark Day,” and fans showered him with gifts such as a new glove, new spikes, a lounging robe and a travel kit. Clark had been recommended to Phillies scout Eddie Krajnik by Harry and Herman Layne, twin brothers from Mason County who had storied minor league careers, and that recommendation carried enough weight to overcome a bad workout.

“He had never seen me before,” Clark said. “He said the Layne boys said he should take a look at me because one of things they liked was that every time I swung the bat, I seemed to make some sort of contact, whether it was foul or fair. He met me in Parkersburg, and I had a terrible workout. I couldn’t have impressed him at all. It seemed like I couldn’t do anything right. But he said, based on what the Layne boys had said and the report he had on me, he wanted to sign me. That’s when I decided to sign.”

Krajnik called Clark “one of the finest prospects I have seen in 15 years. If he carries with him the same amount of determination he has now, I don’t see how he can miss the big show,” Krajnik told the Parkersburg newspapers. Prior to signing with the Phillies, Clark had also talked with representatives from the Yankees, Red Sox, Reds, Browns and Pirates.

The Phillies initially did not need Clark in their minor league system and allowed him to remain with Parkersburg for the summer. After signing with Philadelphia, which had not been made public yet, he was invited to Marion, Ohio, to try out for the St. Louis Cardinals. He at first did not want to go, wanting to remain loyal to the Phillies. But Clarence Fisher, another former big leaguer and Mason County native, talked him into it.

“I went up there under a different name,” Clark said. “Roush is a pretty common name around here, so I went up there as Roush. I never had such a workout in my life. It seemed like everything I hit was going out of the park in batting practice. They wanted to sign me immediately, but I had already signed with the Phillies. About two weeks later, we’re playing a

game at Wahama, and I hear somebody keep yelling ‘Roush.’ It was that same guy from the Cardinals still trying to sign me.”

On July 27, 1947, Clark received a message from the Philadelphia brass asking him to report to Schenectady, New York, to play for the Class C team in the Canadian-American League. But a phone call from Krajnik redirected Clark to Americus, Georgia, to play for the Phillies in the Class D Georgia-Florida League. Before he could leave his hotel, Clark again received a call from Krajnik, telling him instead to report to Bradford, Pennsylvania, in the Class D Pennsylvania-Ohio-New York League because it needed a third baseman to finish the season. Clark packed up and headed to Bradford on a bus, but barely had time to unpack. After one day, he was instead told he was needed by the Appleton (Wisconsin) Papermakers in the Class D Wisconsin State League. This time, however, he traveled by train to his Midwestern destination. He arrived at the station around 4 p.m. and was met by club officials, who drove him to Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, where the Papermakers were playing a 6 p.m. doubleheader against the home-standing White Sox. He hustled into his uniform, foregoing infield and batting practice, and took his position at third base. His first two professional at-bats produced a run-scoring triple followed by an RBI-single. He turned a double play on the first ball hit to him in the field. After a couple of weeks, Appleton found itself needing an outfielder because of injuries. Clark offered his services as the manager was seeking volunteers.

“We had an extra infielder, so they moved me to the outfield,” he said. “That’s where I stayed. I occasionally filled in at third base for a game or two when they needed one. I would always take infield after I got my outfield practice in.”

Clark made the most of his opportunity, hitting .347 in 41 games with a homer and 18 runs batted in. Appleton finished the year 61-61, good enough for a fourth-place tie, some 21 games back of league champion Sheboygan.

In the off-season, Clark returned to the Ohio University campus to continue his pursuit of a bachelor’s degree in business and finance. He did find time, February 28, 1948, to be exact, to marry his hometown sweetheart, Sally Lou Roush. The newly married outfielder was allowed to report to spring training in Tennessee a bit later than the rest so that he could finish his college semester. He was assigned to the Class D Baton Rouge (Louisiana) Red Sticks of the Evangeline League. His delayed debut did not hinder his progress, as he earned the starting job in center field. He was among the league’s top hitters all season, batting .371 at the mid-point to earn a spot on the all-star team for the eastern half of the league. He went 1-for-3 in the All-Star Game and made “a brilliant catch” against the center field wall, according to newspaper accounts. Baton Rouge, 72-65, finished fourth in 1948 and was tied at a game apiece with the Houma (Louisiana) Indians when a post-season storm cancelled the playoffs. His worth to the team also showed itself in other ways that season.

“They didn’t pay minor leaguers very much money back then,” he recalled. “Our bus driver got another job and quit. I told them that I would drive the bus since I have to go on the trips any way. I drove the bus, and they paid me the extra money, what they were paying the other bus driver.”Clark again hit .347, slamming out 191 hits in just 137 games. He showed flashes of power with eight home runs and 91 runs batted in. He set the league mark for triples with 22, a record that stood until the Evageline League ceased operations after the 1957 season.

“The league record down there was 18 triples, and I had 17,” Clark said. “I hit a ball to right-center, and I knew I was going for a triple. I went into third easy, and they threw the ball back to first base. They called me out for missing first base. That would have tied the record. I went on to end the season with 22 triples.”

That season also proved vital to Clark’s ascension to the big leagues. Clark credited his manager, Dick Carter, for being responsible for his reaching the Phillies a few years later. Carter also put Clark in the outfield full-time.

“He would run me to right-center, left-center, make me come in and make me go back,” Clark said. “He was a great guy. He talked to the home office all the time, and I’m sure he was the one who got me to the Phillies.” The Phillies weren’t calling just yet, as they were still a season away from their “Whiz Kids” fame. Skipping both Class C and Class B coming out of spring training, Clark was assigned to the Utica (New York) Blue Sox in the Class A Eastern League for the 1949 season. A new team brought on a new name, as he became known as Melvin instead of Earl. Whatever the name, he got off to his customary hot start, hitting around .340 as of May.

But a bout with strep throat weakened him as the summer heated up, and he was later diagnosed with viral pneumonia. His high fever forced him to return to his home in West Virginia to recover. When he came off the disabled list, he was sent to Class B Terre Haute, Indiana, to finish the season. For the season, Clark hit .252 with two homers and 24 RBI at Utica, before finishing at .292-0-20 in 33 games with Terre Haute.

Fully recovered over the winter and now armed with a bachelor’s degree from Ohio University, Clark — now known as Mel — returned to Utica for the 1950 season and was reunited with Lee Riley, his manager from Terre Haute. Riley, the father of legendary NBA coach Pat Riley, helped Clark to return to his usual offensive potency. The late start because of college

classes again proved to be of no hindrance, and Clark’s .332 batting average was the third highest in the Eastern League. He stroked 19 doubles and seven triples along the way, driving in 62 runs and scoring 59. Scouts rated Clark as “one of the smoothest fly chasers in the Eastern League and one of the most dangerous sluggers, too.”

The 1951 season looked full of promise for Clark. The Phillies were coming off a pennant, and Clark was just a step away from the big club after being assigned to Class AAA Baltimore. Clark was battling Danny Schell for a spot in an overcrowded outfield, and on April 18, 1951, Clark was sent back to the Eastern League, but this time to Schenectady, New York, as the affiliation had been transferred. The move did not sit well with Clark; after all, he had gone 5-for-5, hitting for the cycle with a single, two doubles, a triple and home run on the last day of spring training. He entertained thoughts of retiring, while demanding to know why he was returning to a place where he had already proven himself.

“They said they wanted me to play for the same manager another year,” Clark recalled. “That kind of upset me. I told them to tell (Phillies owner) Bob Carpenter that if he needed me, he could call me at home. I went in the next day to get all of my gear, and there was a message that Mr. Carpenter wanted to meet with me in Philadelphia if I would come there.” The Clarks drove to Philadelphia for the meeting, and Carpenter offered Clark a bit more money to return to Schenectady for the 1951 season. The agreement also included a chance to make the Phillies’ big roster for the 1952 season. Clark told the owner that it would be almost impossible for him to have a better season this time around, and Clark learned that having better statistics was not the most important thing in the world.

Fueled by either frustration or fervor, Clark slammed three homers in his first 14 games upon his return to the Blue Jays. His batting average rose to near .330 by mid-season, and his new-found power stroke was being noticed by those higher up. A late-season slump pulled his average down around .280, prompting a visit from the farm system director. Clark said there was no problem, he wasn’t striking out. It was just that the baseballs he hit were finding their way into the fielders’ gloves. He surged to bring his average back to around .300, and that brought another chance meeting with the farm director in the lobby of a Scranton, Pennsylvania, hotel. “He was talking to me, and as I was getting ready to leave, he handed me a little envelope,” Clark said. “He said to read it when I had the time. I opened the envelope and there was $500 in it and a note that said, ‘This is for having confidence in yourself when I talked to you earlier in July.’ I later thanked him for that.”

Clark’s .294 average was the third highest on the team, and he led the Blue Jays with 87 RBI. His 29 doubles was the best in the Eastern League, and that was accompanied by 10 triples and his career-best season of 10 homers. After concluding the season in Binghamton, New York, Clark received the call he had long awaited. He was to join the Phillies, who were playing in Pittsburgh. He got back to Schenectady around 1 a.m., picking up his wife Sally, who had packed up the couple’s belongings after learning of her husband’s promotion. They left around 3 a.m. for the long-dreamed of trip to the big leagues. The couple arrived in Pittsburgh around 3 p.m. September 11, 1951, just prior to being needed for 6 p.m. batting practice. The Clarks grabbed a quick bite to eat and checked into the Schenley Hotel, almost next door to Forbes Field. Though Philadelphia was mired in fifth place and 23 ½ games behind first-place Brooklyn, Clark viewed his new teammates as supermen.

“I had always idolized those guys,” he said. “I introduced myself to [Phillies manager] Mr. [Eddie] Sawyer, and he introduced me to the players, told them I was joining them. He told me to go work out in right field because I was playing right field and batting fifth. I hadn’t had any rest, and I said, ‘Good, that’s what I’m here for.’”

In a moment forever etched into his memory, Clark lined his first batting practice pitch off the Forbes Field clock in left field. Future Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn was standing behind the batting cage and remarked, “Holy cow! There goes my job.” Veteran Bill Nicholson took Clark out to right field after batting practice to teach him how to play the angular right field wall and slopes at Forbes Field. Clark said Nicholson’s tutelage relaxed Clark as his debut approached. Robin Roberts was scheduled to start for the Phillies against the Pirates’ rookie right-hander Don Carlsen. Clark singled in each of his first two at-bats, and Willie Jones hit a two-run homer in the seventh to give Philadelphia a 3-2 win, snapping a six-game losing skid in the process. His performance earned him another starting shot the following night, and Clark again made the most of his opportunity. He slammed his first big league homer, a solo shot in the second inning off left-hander Howie Pollet. Clark hit only three career home runs, two of which were served up by Pollet. He finished the second game of his big league career with a 3-for-5 night at the plate. “Then we went to Cincinnati, and I had three hits in that game,” Clark recalled. “I was 8 for 14, and I thought that this was a snap. Then the next game, I was 0 for 4. But that’s the way it goes.”

In all, Clark saw action in 10 of the Phillies’ final 15 games, batting .323 with a homer and three RBI. He was invited to spring training in 1952 with the big club for the first time in his career, having a chance to catch on as a fourth outfielder or beat out Johnny Wyrostek for the right field job. Ashburn was entrenched in center field, and hard-hitting Del Ennis patrolled left. He turned in a solid spring, hitting .333 which he credited to his using a new bat confiscated by teammate Putsy Caballero from Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky, Clark made the team when it broke camp, but he broke a bone in his hand on April 19, which kept him sidelined for nearly three weeks. He returned to the lineup May 4 and knocked a single and a triple in a game against the Reds. Philadelphia, however, had started slowly, and Sawyer resigned as the team’s manager in June. Steve O’Neill replaced Sawyer, and the Phillies responded with a 59-32 mark to finish in fourth place. Clark saw action mostly as part of an outfield platoon system, and he even returned to his old spot at third base for one game. He finished the season with a .335 batting average, a homer (a grand slam on July 15 off of Pollet in Pittsburgh with his parents in the stands, unbeknownst to Clark until afterward) and 15 RBI in 155 at-bats.

Clark returned home to Mason County a celebrity during the winter of 1952-53, spending a lot of time speaking to school children and civic organizations. Though he had played mainly against left-handed pitching in 1952, it was widely believed Clark had the inside track for the starting job in right field for the 1953 season. He would again battle Wyrostek for playing time, but John Mayo, Bill Nicholson and Joe Tesauro were thrown into the mix for the upcoming year. The Phillies were so deep in the outfield that they were trying to package Clark, Mayo, pitcher Paul Stuffel and first baseman Eddie Waitkus in a deal with Pittsburgh for outfielder Ralph Kiner. The deal fell through, and Clark reported to Florida with the Phillies. Spring training was a bit bumpier this time around, as Clark was injured in a game against Brooklyn. Setting up to throw to the plate with Don Zimmer tagging at third, Clark misplayed a ball coming out of the sun. He required a dozen stitches to close a gash on his head. It was the less serious of the two injuries he suffered during the 1953 campaign.

“We went into Cincinnati, and I hadn’t been playing much,” Clark said. “Mr. O’Neill made a drastic change because we had been losing. He put about five players in the lineup that hadn’t been playing, and he put me into left field for Del Ennis. I had two or three hits in that game, and we won three out of four in Cincinnati. Then we went to St. Louis, and I played in all four games. We won three out of four from them. I was playing well when we went to Milwaukee. Then the manager called me aside — Del Ennis was one of our top players, and he had trading value — and he told me, ‘I’ve got to put Ennis back in the lineup, but don’t ask me why.’ I knew it was because if they were going to trade him, they could get more out of him than they could if he wasn’t playing.”

In July, Clark injured his knee in a home plate collision with Dodger catcher Roy Campanella, but kept quiet about it. A few days later in Cincinnati, Clark came in to field a base hit into right field, but had his knee give way. The baseball rolled 10 feet past him, allowing the runner to reach second base and giving Clark his first big league error after two years. He still kept quiet abut his injury until he tried to chase down a fly ball in Milwaukee, only to have his knee fail him again. He told the manager about the problem and was later sent back to Philadelphia for an appointment with team doctors.

A season which saw him bat .298 with 19 RBI in 198 at-bats came to an early end on September 8 when he was ordered to undergo treatment at Temple University’s hospital. The knee would continue to plague him the remainder of his career. That same month, the Clarks welcomed their first child, son Brent, who was born at a hospital in Gallipolis, Ohio, just across the river from their off-season home.

The 1954 season was one of mixed blessings for Clark. Playing in a career-high 83 games, he also drove in a career-best 24 runs in 233 at-bats. But his .240 batting average was the worst of his entire professional career. He slammed the final home run of his major league career on July 17, a solo shot off Cincinnati’s Jackie Collum. Despite his struggles, he was still a star back in his hometown. Bennie and Tommy Franklin, the sons of a local Point Pleasant store owner, started the Mel Clark Fan Club. Dues were 10 cents to join and 10 cents a month to “keep out the riff raff,” they said. Clark was also named by the Schenectady newspaper as the best all-around player to ever play in that town. During that season, Terry Moore replaced O’Neill as the Phillies manager. Frustrated by being used mainly as a pinch-hitter, Clark asked his new skipper for a chance to prove himself.

“He put me in the lineup the next day, and I hit in something like 27 of the next 28 games,” Clark said. “I had a 19-game hitting streak. He said, ‘I’ll give you credit for helping us move up [through the standings. The Phillies finished fourth.] You did a great job and don’t worry about next year. If I’m still around, you’re going to be my regular right fielder.”‘

Moore, however, was relieved of his duties during the winter and replaced by Mayo Smith. Over the winter, Clark made plans for life outside of baseball, buying into a Point Pleasant, West Virginia, automobile dealership where he had previously worked as a car salesman. Smith had his own ideas of running the Phillies, and several of the previous players did not fit into his plans. Smith told catcher Smoky Burgess that his starting days were over, this coming after a season in which Burgess hit .345. Clark also did not figure into Smith’s plans. Clark played in only a handful of spring training games, but still went north with the team. Playing in only 10 games and hitting .156, Clark was optioned to Syracuse, New York, in the International League when it came time to trim the rosters down to 25 players. He learned of the move during a train ride to St. Louis. The move, he recalled, surprised his teammates. Clark entertained thoughts of retirement as his family had just welcomed a new child, daughter Barbara, in May. But a promise to be recalled if he played well led him to report.

Clark hit .303-6-43 in 92 games with Syracuse, but the promised promotion never materialized. He held out during the 1956 spring training because he was assigned to Miami, a team with which Philadelphia had a working agreement in the International League. He was again working out as a third baseman. “He told me that if I had guts enough to try him at third base, he was willing to do it,” Miami manager Don Osborn said. “I like that kind of spirit.” This time, the delayed start to his season affected his performance. He was hitting just .225 with a home run and nine RBI in 63 games with the Marlins when word came down he had been traded to the Louisville Colonels as part of a seven-player deal on July 7. The deal was controversial because the Phillies had not obtained Miami’s permission prior to the deal, which essentially made Clark the property of the Washington Senators although he never signed a contract with that team. Clark had learned about being traded when he saw the article in the local newspaper. Going to the American Association proved to be a catalyst for Clark, who responded by batting .310 with seven home runs and 36 RBI in 57 games for Louisville, which finished last in the league with a 60-93 mark.

A free agent over the winter, Clark saw his contract picked up by the Detroit Tigers for the 1957 season. The Tigers wanted to send Clark to its American Association team in Charleston, West Virginia, which was just an hour’s drive from his West Columbia home. But Clark thought differently and called general manager John McHale to plead his case. McHale agreed to bring Clark to spring training as a non-roster player, but leave his contract with Charleston. With another opportunity, Clark tore up spring training pitching, and his .448 batting average won him a spot on the Tigers. But despite manager Jack Tighe‘s predictions of a glorious season, Clark found himself relegated to the bench when the season opened. About a month later, Clark was told he would be going to Charleston for more playing time. He initially returned home, not knowing if he would play another day in Organized Baseball. He finally relented and reported to Watt Powell Park to join the Senators. Clark turned in a respectable .285-7-48 in 114 games in 1957, hoping it would be enough to earn a trip back to Detroit.

“The flying and the traveling conditions were terrible in Charleston,” he remembered. “We had a little old DC-3 plane. You would leave Omaha, Nebraska, after a night game and fly back to Charleston to play a doubleheader the next afternoon. It just wasn’t good.”

Clark asked to play in Birmingham, Alabama, the Tigers’ Southern Association team in Class AA ball for the 1958 season if he did not have a spot on a major league team. Detroit management initially balked at paying Clark’s salary to play at a lower level, but finally relented. His 42 doubles led the league, and he turned in a professional-best 96 RBI to go along with a .295 batting average and nine round-trippers. Birmingham won the league with a 91-62 record, and then bested both Chattanooga and Mobile in the post-season rounds. The Tigers sold his contract for the 1959 season to Fort Worth, Texas, a team under the control of the Chicago Cubs. But Clark opted for retirement and returned to the place where it had all started for him, the Parkersburg Scotties.

The Phillies came calling a few years later, seeking Clark’s services as an assignment scout. He reported back on infielders Terry Harmon and Mike Schmidt while they were playing at Ohio University, and both signed with Philadelphia. Clark also signed pitcher Billy Wilson, who grew up across the river from Clark in Pomeroy, Ohio. Wilson served as a relief pitcher for five seasons with the Phillies, compiling a 9-13 record. Clark signed infielder Morehead State (Kentucky) University infielder Denny Doyle to a contract after a workout at a Little League clinic in Ashland, Kentucky

Clark spent his baseball retirement years coaching American Legion baseball, selling cars and later insurance, scouting, and watching his children grow up. His daughter Barbara and her husband are raising their family near Youngstown, Ohio. His son Brent was graduated from West Point and played baseball there, later coaching briefly at Rio Grande (Ohio) College following his retirement from the military.

Sources

The West Virginia Sports Writers Association

www.retrosheet.org

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

The Baseball Encyclopedia, 9th Edition.

www.baseballreference.com

www.minorleaguebaseball.com

Johnson, Lloyd and Wolff, Miles, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Edition.

Crehan, Herb, “Denny Doyle.” Society for American Baseball Research’s Biography Project

Interviews and conversations with Mel Clark

Mel Clark’s personal scrapbook

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Melvin Earl Clark

Born

July 7, 1924 at Letart, WV (USA)

Died

May 1, 2014 at West Columbia, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.