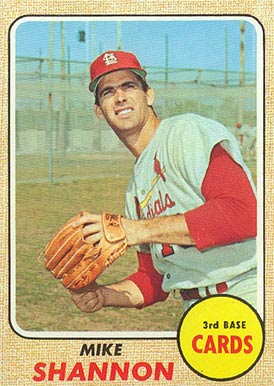

Mike Shannon

For more than 50 years, Mike Shannon has been a fixture in the Cardinals’ organization. He played for his hometown team and was a member of three pennant-winning teams and two World Series champions. He became a hometown hero with a game-tying home run at Busch Stadium that helped win the first game of the 1964 World Series. A selfless player, he gave up his personal comfort for the betterment of the team when he learned to catch and later switched from the outfield to third base. His playing career was prematurely ended by a life-threatening kidney ailment, but it led to a successful 40-year broadcasting career with the Cardinals.

For more than 50 years, Mike Shannon has been a fixture in the Cardinals’ organization. He played for his hometown team and was a member of three pennant-winning teams and two World Series champions. He became a hometown hero with a game-tying home run at Busch Stadium that helped win the first game of the 1964 World Series. A selfless player, he gave up his personal comfort for the betterment of the team when he learned to catch and later switched from the outfield to third base. His playing career was prematurely ended by a life-threatening kidney ailment, but it led to a successful 40-year broadcasting career with the Cardinals.

Thomas Michael Shannon was born in St. Louis on July 15, 1939, the first child of Thomas W. and Elizabeth (Richason) Shannon, and attended Epiphany of Our Lord parish school. Growing up, he played various sports depending on the time of year. His father was a police officer working his way through law school, but still he took time to help Mike improve his skills. Shannon developed into an exceptional three-sport athlete at Christian Brothers College (high school) in nearby Clayton, Missouri. As a senior, he was the starting quarterback for the undefeated football team and was voted a high-school All-American. He won Missouri prep Player of the Year honors in football and basketball, the only player to receive both awards in different sports in the same year.1

Shannon felt he was a better football player than baseball player, but at the time it was baseball, not football, that offered the best opportunity for a professional career. “Back then, there wasn’t any money in football,” he recalled. “If there would have been, I would have stayed with football.” His baseball talent was “really raw” by his own admission and no team offered him more than an $8,000 signing bonus. Stan Musial , whose son Dick was Shannon’s high-school teammate, told Shannon that the rule requiring players with large bonuses to be on the major-league roster for two years would soon change. Shannon decided to attend college and wait for a better offer. He was offered football scholarships by colleges across the country and accepted the one from the University of Missouri.2 But in June 1958 Shannon signed with the Cardinals for a bonus of close to $50,000. “I liked football, but baseball was always my first love,” he later said.3 The Cardinals sent the 17-year-old to play for Albany (Georgia) of the Class D Georgia-Florida League. Playing center field in his debut, he drove in the winning run in the first game of a doubleheader and helped win the second with a 400-foot double. Shannon batted .322, hit six home runs, and was named to the postseason All-Star team, even though injuries limited him to 62 games—“I dislocated a shoulder diving back into second base, I was hit on the head by a ball when I stole third base and I got a broken nose diving for a line drive,” he recalled. After hitting a home run in the 1964 World Series, he recalled hitting a longer one for Albany, in Dublin—“Dublin, Georgia, of course. I really shillaleghed that one.”4

Shannon married his high-school sweetheart, Judith Ann Bufe, in St. Louis on February 7, 1959. She traveled with him to spring training and through the minor leagues even after their children (three sons and three daughters) were born. “It was Judy who took care of the family and made it possible for me to enjoy my career,” he said.5 By 1960 he was playing in Double-A and in 1961 he was in Triple-A, with Portland in the Pacific Coast League. There he earned the nickname Moonman for the way he dodged out of the way of a pitch behind his back. “It looked like I was floating in mid-air,” Shannon recalled; a teammate thought he “looks like a moon man.” Future teammates, however, believed there was a quirkier reason behind it. “He’ll talk 15 minutes and when he’s through you’ll go away scratching your head and wondering what he said,” Bob Gibson remarked. “He may start a conversation about baseball and end up with insurance after going through 45 other topics. You still don’t know what he said.”6

Shannon was among four minor-league prospects invited to the major-league camp for spring training in 1962, but he was sent back to Triple-A when camp broke. He spent the first half of the season with the Atlanta Crackers in the International League, then was traded in August to the Seattle Rainiers, the Boston Red Sox’ Triple-A club in the Pacific Coast League, where he batted .311 in 76 games. The Cardinals reclaimed him and brought him up to St. Louis, where he made his major-league debut in right field against the Cincinnati Reds at Busch Stadium on September 11, 1962. In his second at-bat he hit a single to left field. “You always remember that first at-bat and first hit,” Shannon said. “Mine came against a pitcher Bob Purkey , who was one of the best in the majors at the time”—Purkey went 23-5 that season—“and it was a confidence builder to be successful.”7 The Cardinals thought enough of his potential that they placed him on the 40-man roster and invited him to play in the Florida Winter Instructional League.8

The 1963 season was a difficult one for Shannon. He made a poor showing in spring training and was sent down to Triple-A Atlanta. His wife, Judy, pregnant with their fourth child and seriously ill, was bedridden and couldn’t care for their three young children. Shannon missed the first half of the season and though he returned to Atlanta in early July, he considered quitting until his wife was better. To allow him to stay close to home, the Cardinals promoted him to the major-league roster on July 21 and he stayed with the team the rest of the season, getting 21 at-bats as an outfield defensive replacement for Stan Musial and others.9 Before his last major-league game, on September 29, Musial pointed to former Cardinal Joe Medwick and said, “This is the guy I replaced as regular left fielder 22 years ago.” Then he motioned to Shannon and fellow outfielder Gary Kolb , sitting on either side of him: “And these are my protégés who’ll replace me next year.”10

In the offseason St. Louis offered Shannon to the Milwaukee Braves in a deal for reserve catcher Bob Uecker , but the deal was not made, and Shannon went north with the Cardinals after spring training.11 After three weeks riding the bench with little playing time, he was sent down to Triple-A Jacksonville. Now out of options and subject to the minor-league draft if the Cardinals did not bring him back by the end of the season, Shannon decided to make the most of his demotion. “I made up my mind to work as hard as I could to improve my hitting. … I had to,” he said. “I’ve got a wife and four kids at home.” He also gave himself a deadline for returning to the majors. “I figured, if I don’t come up by this date, I’m kidding myself. I’d better find a job and go to work someplace.” Batting leadoff for Jacksonville, Shannon hit .278 with 11 home runs in 70 games; on July 9, he returned to St. Louis. “I just beat the mark, that’s all,” he said of his deadline. “By about a week or 10 days, I beat it.” He became the starting right fielder for a team poised to make a remarkable comeback.12

When Shannon joined the Cardinals they were in sixth place in the ten-team National League with a record of 39-41 and 11 games behind the Philadelphia Phillies. He batted .351 in July with 17 RBIs, but cooled to a .203 average and nine RBIs in August as the team climbed into fourth place, 7½ games behind Philadelphia. Shannon proved adept at gunning out baserunners and notched seven outfield assists. The Cardinals surged in September, winning 22 games to place themselves back in contention. A ten-game Phillies losing streak down the stretch coincided with the Cardinals’ longest winning streak of the season—eight games—to lift St. Louis past the Cincinnati Reds into first place on September 30. Two losses to the last-place New York Mets left the Cardinals in a first-place tie with the Reds. In the second inning of the crucial final game of the season, Shannon singled Tim McCarver home with the first run against the Mets. Later the Cardinals bounced back from a 3-2 deficit for an 11-5 win which—coupled with Cincinnati’s 10-0 loss to Philadelphia—clinched the pennant for St. Louis.13

In the World Series, the Cardinals faced the New York Yankees. It was a dream come true for Shannon, though he had only six hits for a .214 average and struck out five consecutive times in the seven-game series. But one of those hits was pivotal in the team’s 9-5 victory in Game One at Busch Stadium. With one out in the sixth inning, Ken Boyer on second base, and the Cardinals behind 4-2, he faced Whitey Ford, who was pitching in his 22nd and final World Series game. Ford hung a slider and Shannon belted it over the left-field wall and against the top of the 75-foot-high scoreboard, striking the U in the BUDWEISER sign and tying the contest. St. Louis scored twice more in the inning and won, 9-5. “That homer gave me the biggest thrill of my life,” he said at the time. Twenty-five years later, he recalled: “I was a hometown boy in front of the hometown crowd, and I hit a home run off Whitey Ford in the World Series. You can’t hardly top that.”14 Before Game Two Shannon found out that it would cost more than $4,000 to repair the sign. He walked to owner August Busch ’s box seat and apologized for the damage. Busch laughed and said he didn’t care if Shannon hit a couple more off the sign during the Series. Shannon hit no more home runs but had two outfield assists, and in Game Seven he and McCarver pulled off a double steal for the second run, then Shannon scored on a single by Dal Maxvill as the Cardinals went on to defeat the Yankees and win the Series.

Shannon’s line-drive bat and strong throwing arm earned him the right-field berth in 1965. He hit well in spring training, but struggled at the plate during the season and ended with a .221 average. “I just put myself in a slump by pressing,” he said. “I’d keep saying to myself, ‘I got to get a hit this time. I got to get a hit this time.’ I worried that if I didn’t get the hit, I probably wouldn’t get to play the next game.” On September 25, at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, he fell victim to Sandy Koufax ’s 350th strikeout, which set a major-league single-season record. (Koufax finished with 382 strikeouts.)15

While disappointed with Shannon’s bat, new Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst was impressed with his versatility. Former manager Johnny Keane had tinkered in 1964 with the idea of the rifle-armed Shannon being an emergency catcher, but it didn’t come to fruition until August 8, 1965. McCarver was injured, and Bob Uecker, starting in his place, split his right thumb on a foul ball in the first inning against the San Francisco Giants. Shannon was called upon to replace him. “When they handed me Uecker’s mitt, an ounce or two of blood spilled out of it,” he recalled. “That’s when I wasn’t so sure I wanted to go out there and catch.”16 Despite a few mishaps—like putting shin guards on the wrong legs and “sticking my hand straight down, instead of holding it against the inside of my leg” when giving signals to the pitcher—Shannon did a good job handling five pitchers (including knuckleball reliever Barney Schultz ) and turned a double play by tagging out Willie Mays trying to score on Jim Ray Hart ’s double and then throwing out Hart advancing to third.17

At the end of the season Shannon went to the Florida Instructional League to learn catching fundamentals and work on his hitting. “We’re figuring him as an outfielder yet, but this gives him a chance to do many things,” said general manager Bob Howsam . It was a tumultuous offseason as the Cardinals traded stalwarts Ken Boyer, Bill White , and Dick Groat and acquired outfielder Alex Johnson from Philadelphia. Johnson was considered the favorite to win a starting job and Shanon hoped that if he was blocked from an everyday role in the outfield, he might be a reserve catcher. “I feel that I sharpened up enough at catching that I could step in right now and do a good job in a regular season game,” he said after the Instructional League season ended.

Once again, Shannon made a good showing with the bat in spring training but he found himself on the bench to start the 1966 season. When the highly-touted Johnson slumped early in the season, Shannon got the opportunity to play more often. In the last game played at Busch Stadium (formerly Sportsman’s Park), on May 8, his fifth-inning solo home run against San Francisco was the last one hit there by a Cardinal; Willie McCovey and Willie Mays homered later for the Giants at the historic ballpark. When Busch Stadium II opened, on May 12, he had the first Cardinal hit, a single; the next night he hit the first Cardinal homer, a solo shot in the fourth inning. Still, he was unhappy being part of an outfield platoon with Johnson and rookie Bobby Tolan , and considered playing football again (he had been invited to try out with the Atlanta Falcons). But a torrid hitting streak in July that led teammates to nickname him the Cannon quelled his gridiron aspirations and made it hard for him to sit on the bench. He batted .395 with 45 hits and 23 RBIs for the month, including a 4-for-5 performance with three runs scored at Cincinnati on his 27th birthday; a week later in Chicago he went 5-for-5 with a home run, double, and three runs scored. “Shannon has been a big reason for our team’s recent improvement,” Schoendienst said. Though the Cardinals finished in sixth place, he enjoyed his best major-league season to date, batting .288 with 16 home runs and 64 RBIs in 124 games.18

Shannon’s breakout performance convinced the team that he should be an everyday player, but with the added challenge of learning yet another position. Schoendienst was confident that Shannon could make the transition to third base and make room in right field for Roger Maris , acquired over the winter from the New York Yankees. (He and Maris became close friends and Shannon was a pallbearer at his funeral in 1985.) Though his strong, accurate throwing arm made him one of the top outfielders in the league, he agreed to the switch and fielded countless bunts and groundballs during the winter and spring training to prepare for it. “Listen, nobody has to tell me about how I play third,” Shannon candidly admitted about his defense. “Nobody playing the game looks worse than I do when I’m going badly. But over the long haul I think I can do the job.” Though his batting average fell to .245 and he committed 29 errors at the hot corner, he contributed 12 home runs and 77 RBIs (second on the club behind National League MVP Orlando Cepeda ) despite injuries and illness in spring training and during the first half of the 1967 season. General Manager Stan Musial said Shannon’s willingness to move to third enabled him to add more offense to the team: “There’s no question but that Shannon agreeing to take a shot at third base set up our club,” Musial said. The Cardinals captured the pennant and faced the Boston Red Sox in the World Series. In Game Three, his second-inning two-run homer (the first ever hit in the postseason at Busch Stadium II) put St. Louis ahead 3-0 in the Cardinals’ 5-2 victory over Boston. Shannon batted just .208 in the Series, but St. Louis won it in seven games. “Every time we win a pennant, I have to play a new position,” he joked. “I hope that I’m pitching next year if we win.”19

Fortunately for Shannon, there was no new position for him to learn in 1968. His fielding at third base improved, with fewer errors, but more importantly he had his best season at the plate, leading the Cardinals in RBIs (79) and finishing seventh in the MVP voting while batting .266 with 15 home runs (second best on the club). The team won the pennant again and played the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. Shannon enjoyed his best postseason performance with eight hits in 29 at-bats and four RBIs, but St. Louis dropped the Series in seven games. Shannon’s ninth-inning home run at Busch Stadium (giving him a homer in each World Series he played in) was the only blemish on Detroit left-hander Mickey Lolich ’s 4-1 victory in Game Seven. Afterward, the Cardinals embarked on an 18-game goodwill tour of Japan and won 13 games against the host teams. Shannon, Lou Brock , and Orlando Cepeda led the team with five home runs each.20

Coming off their second straight pennant, the Cardinals were the favorites to win it again in 1969. Shannon and his teammates did well in spring training, but they struggled when the season began and were 15½ games behind the Chicago Cubs in the East division standings on July 4. A midsummer resurgence wasn’t enough to overcome the Cubs or the division-winning Mets, however, and the team finished in fourth place. Shannon’s numbers dropped from the previous season to a .254 batting average and 12 home runs, while his RBI total fell to 55.21

There were rumors over the winter that he might be dealt to the California Angels, but Shannon was still a Cardinal when spring training began in 1970. During the players’ physical exams it was discovered that he had glomerulonephritis, a potentially life-threatening condition that prevents the kidneys from filtering waste properly. The team physician, Dr. Stan London, told the 30-year-old Shannon that he might miss the entire season. “The severity of exercise could be injurious to his health,” London said. “His condition could have been aggravated by his playing baseball.” Before his diagnosis, the Philadelphia Phillies were interested in Shannon to replace Curt Flood (who had refused to be traded) in the deal that sent Dick Allen to the Cardinals. “He was that close to not making it,” remembered Cardinals broadcaster Jack Buck , spreading two fingers slightly apart on his hand. “A lot of people thought he was going to die.” After a month of medication and rest at Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Shannon was allowed to begin workouts for a possible comeback. “I’ve got a clean bill of health,” he announced upon his return to the club. “There’s nothing wrong with me that a few base hits won’t cure.” He made his season debut as a pinch-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates in a home game on May 14 and got a standing ovation. The comeback was understandably difficult and Shannon batted just .213 in 193 plate appearances with no home runs and 22 RBIs. On August 14 Dr. London determined that his condition had worsened and he would have to resume treatments and not play the rest of the season.22

A possible return in 1971 was ruled out before spring training and Shannon accepted an offer from the Cardinals to serve as assistant director of promotions and sales in the front office. “There’s not much difference” between his new position and being on the field, he said. “Now, I’m just promoting the game from behind a desk instead of from behind third base.” After the season, General Manager Bing Devine offered him the chance to manage the Cardinals’ Triple-A Tulsa club or be a major-league coach, but he turned both down for financial reasons and to stay close to his family.23

Rather than attempt a second comeback at 32 years old, Shannon accepted a new challenge. He became the color commentator on the Cardinals’ radio and TV broadcasts alongside announcer Jack Buck for the 1972 season. “It was an easy decision because I had six small children, and I had to educate them,” he recalled. “I thought the opportunity was better in broadcasting. So I worked as hard as I could to become the best broadcaster I could. It turned out to be the right decision.” Eventually he began sharing the play-by-play duties with Buck. There were times when the transition was not a smooth one as he learned the intricacies of calling a game, but Buck was a patient teacher and Shannon an eager student. “Good Lord of mercy, I don’t know what I would have done without him,” Shannon said. “That man helped me so much. I didn’t have to go to broadcasting school—working with Jack was like having a private tutor [and] on-the-job training.” In 1985 Shannon received a regional Emmy award for sports broadcasting and in 1999 he was inducted as a broadcaster into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame.24

Shannon was still broadcasting in 2011, with a unique broadcasting style that included clichés and distinctive phrases. Games “at the old ballpark” consisted of healthy doses of “stee-rike call!” during a pitch count; “Get up, baby, get up! Oh yeah!” when a Cardinal home run was hit; and “Ol’ Abner has done it again” for a dramatic moment late in the game. Sometimes “deuces are wild” on a 2-2 count and when a pitch was down the middle of the plate, it was “right down central.”An opponent’s drive into the gap with runners on was “a peck of trouble.” Then there were his sometimes off-the-wall remarks that fans affectionately called “Shannon-isms.” Here is a sampling:

“He knew he was out when he heard that right hand go up.”

“It’s raining so hard that I thought it was going to stop.”

“You can’t argue with the weather.”

“Well, he did everything right to get ready for the throw, but if ya ain’t got the hose, the water just won’t come out.”

“This big standing-room-only crowd is settling into their seats.”

“It’s Mother’s Day today, so to all the mothers out there, ‘Happy Birthday.’ ”

“How’d you like to be a bug in Whitey Herzog ’s head this week?”

During an unusual exchange with Jay Randolph on a televised game in 1987, Shannon remarked on the rarity of winning streaks by the Pittsburgh Pirates. “Winning streaks in Pittsburgh have been about as common as 600-acre lakes in the middle of the Sahara Desert,” he said. “You mean, like an oasis,” Randolph clarified. “Yeah, well, an oasis is what they’re having here in Pittsburgh,” Shannon replied.25

Shannon and Buck worked together for 30 seasons. Shannon also became a partner in a downtown St. Louis restaurant called Mike Shannon’s Steaks and Seafood. After Buck’s death in 2002, Shannon became the primary play-by-play announcer. As of 2011, he shared the broadcast booth with John Rooney, his on-air partner since 2006, and had signed a contract to continue as the voice of the Cardinals until at least 2013.26

Mike Shannon became an enduring—and endearing—part of Cardinals baseball. Two generations of fans grew up listening to his unpretentious, down-to-earth, and entertaining play-by-play style on the radio. He overcame many obstacles in his personal and professional life—including the death of his wife, Judy, in July 2007—yet kept an optimistic outlook on life and was thankful for every new day.

In September 2011 the Cardinals launched a campaign to encourage fans to nominate him for the 2012 Ford C. Frick Award , the highest honor for broadcasters presented by the Baseball Hall of Fame. It would be a fitting tribute to his 40-year broadcasting career. At 71 years old, he still delighted in the drama and excitement of baseball. “The greatest thing about my job,” he said, “is that when you come to the ballpark, you never know what’s going to happen.” He once said that Stan Musial “is Cardinals baseball, it’s as simple as that.” The same could truly be said for Mike Shannon as well.27

Postscript

Shannon died on April 29, 2023, at the age of 83.

Notes

1 Mike Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame; Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967; Russo, “’Finishing School’ Gives Shannon Start.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 25, 1966

2 David Craft and Tom Owens, Redbirds Revisited: Great Memories and Stories From St. Louis Cardinals (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1990), 206; Dan Caesar, “Tiger QB Saw Future in Cards.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 11, 1991

3 “Mike Shannon Is Signed by Cards for Big Bonus.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 12, 1958; Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library; The Sporting News, June 18, 1958, 19; Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967

4 The Sporting News; Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967

5 Dan Caesar and Pat Bolling, “Mike’s Going ‘Silver.’ ” Cardinals Magazine, October 1995, 23

6 Bob Gibson with Phil Pepe, From Ghetto to Glory: The Story of Bob Gibson (New York: Popular Library, 1968), 128

7 Bob Kuenster, “Players Recall Their Major League Debut.” Baseball Digest, July 2009, 74

8 The Sporting News, October 6, 1962, 32; November 17, 1962, 23

9 Neal Russo, “Shannon Shaping Up as Strong Candidate for Card Picket Post.” The Sporting News, October 19, 1963, 9

10 The Sporting News, May 11, 1963, 8; July 20, 1963, 39; August 3, 1963, 9, October 12, 1963, 19; Bing Devine with Tom Wheatley, The Memories of Bing Devine (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004), 8-9, 11; “Too Young to Remember Series.” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, October 8, 1964, in Mike Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library

11 Neal Russo, “ ‘Great Experiment’ Recalls Cards Almost Goofed.” The Sporting News, February 3, 1968, in Shannon file, Hall of Fame

12 “Mike Shannon … Survivor.” St. Louis Globe Democrat, July 4, 1979. In Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame

13 John Snyder, Cardinals Journal: Year by Year & Day by Day With the St. Louis Cardinals Since 1882 (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006), 475-477

14 David Halberstam, October 1964 (New York: Villard Books, 1994), 320; Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967; Dan O’Neill, “A Storybook Season—Rekindling Memories of 1964.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 29, 1989

15 Neal Russo, “Shannon Has New Name—The Cannon!” The Sporting News, July 23, 1966, 15

16 Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967

17 James K. McGee, “An Irish Comeback.” San Francisco Examiner, June 17, 1967; Neal Russo, “Shannon’s Backyard Ballpark.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1967

18 Neal Russo, “Cards on Wing with Shannon, Buchek Hitting.” The Sporting News, May 28, 1966; Russo, “Shannon.” The Sporting News, July 23, 1966, 15, 20; Sandy Ramras, “Player of the Week.” Sports Illustrated, August 1, 1966. cnnsi.com website (accessed May 10, 2008)

19 Neal Russo, “Switch or Fight? A New Post Spurs Sweating Shannon.” The Sporting News, August 5, 1967, 7; Russo, “Redbirds Saved by Swaps They Failed to Make.” The Sporting News, September 9, 1967, 10; Ralph Ray, “Briles Drives Second Nail into Fading Bosox’ Coffin.” The Sporting News, October 21, 1967, 9

20 Dick Kaegel, “World Champion Bengals Shower with Champagne.” The Sporting News, October 26, 1968, 8

21 Neal Russo, “Cards Flout Laws of Nature, Rise in West and Set in East.” The Sporting News, August 30, 1969, 4

22 The Sporting News, November 8, 1969, 40; December 13, 1969, 44; December 27, 1969, 38; “Ailing Shannon Takes Batting, Fielding Drills.” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970; Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame; Tim Moriarty, “Mike is Back with Will.” Newsday, May 27, 1970; Phil Pepe, “Mike Kicked K-Kidney Ailment.” Unidentified clipping dated May 29, 1970, in Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame; “Cards Ram Pirates 11-7—Shannon a Pinch-Hitter.” Unidentified clipping dated May 15, 1970, in Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame; Dan Caesar, “Shannon Scores: 20 Years Later, Broadcast ‘Project’ is a Pro.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 11, 1991, Neal Russo, “Cards Told Shannon is Out for Season.” The Sporting News, February 27, 1971; Shannon file, Baseball Hall of Fame; “Docs Sideline Mike Shannon.” Unidentified clipping, Shannon file at Baseball Hall of Fame

23 Bing Devine with Tom Wheatley, The Memories of Bing Devine (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004), 13; “Shannon Joins Redbirds’ Promotions-Sales Staff.” The Sporting News, May 1, 1971

24 Dan Caesar, “From Field to Booth—Eight from 1964 Cardinals Become Broadcasters.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 31, 1989; Neal Russo, “Shannon Selects Broadcast Booth.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 5, 1971; “Mike Shannon Joins Buck on Cards’ Radio-TV Team.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 20, 1971, 47. Caesar, “Shannon Scores.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 11, 1991

25 Mike Smith, “Eye Openers.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 16, 1989; Bernie Miklasz, “Mike Shannon’s Not Polished, But He’s Real.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 6, 1989; Mike Eisenbath, “Sunny Side Up: Mike Shannon Likes to Fully Embrace Life.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 11, 1996; “The Mike Shannon-isms Quiz.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch website stltoday.com

26 Dan Caesar, “Cards Re-Sign Radio Broadcasters.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 4, 2011; Spencer Engel, “Press Club Honors Mike Shannon as Media Person of the Year.” St. Louis Beacon, September 30, 2010 (stlbeacon.org website) Accessed September 13, 2011

27 Rick Hummel, “Cards Start ‘Like Mike’ Campaign for Shannon.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 1, 2011; Dan Caesar, “Cards Re-Sign Radio Broadcasters.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 4, 2011; Dan O’Neill, “What Made Stan ‘The Man’?” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 3, 2009

Full Name

Thomas Michael Shannon

Born

July 15, 1939 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

April 29, 2023 at Marion, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.