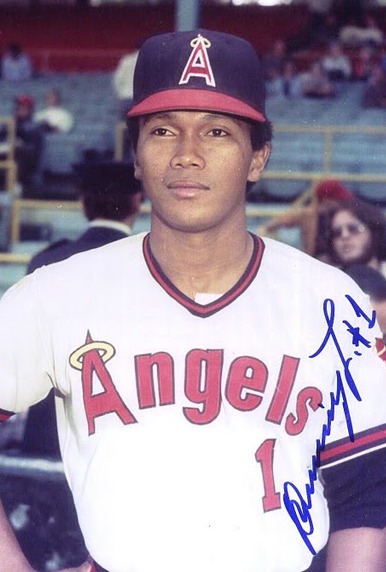

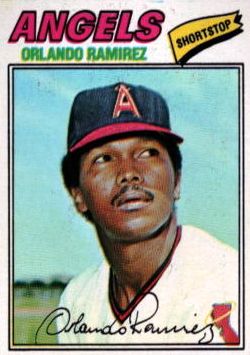

Orlando Ramirez

Acknowledgment to the work of Raúl Porto Cabrales and John Jairo Capella.

Acknowledgment to the work of Raúl Porto Cabrales and John Jairo Capella.

Cartagena, Colombia, is a city of many charms. A UNESCO World Heritage site, it is known for its historic walled district and Spanish colonial architecture. Cartagena also has a pleasant Caribbean climate and beautiful beaches nearby. Yet it has another less heralded distinction as the capital of Colombian baseball. Although this nation had sent just 20 men to the majors as of 2018, 12 of them came from Cartagena – including the first big-leaguer who learned the game in Colombia, shortstop Orlando Ramírez.

El Ñato (which translates as Snub Nose, a fairly common nickname in Latin America) played in 143 games for the California Angels from 1974 to 1979. His was the classic shortstop story: “good field, no hit.” In the spring of 1975, manager Dick Williams said the job was Orlando’s if he managed to hit .200.[1] Over his career, though, Ramírez hit just .189 in 321 plate appearances with the Angels. And while Nolan Ryan called him “Spider” for the way he moved, his .931 fielding percentage at short also fell well short of his reputation.

Although his record at the top level has left him obscure in the United States, his homeland recognizes this man as a pioneer. Since the winter of 2005-06, the Colombian Professional Baseball League has given its Most Valuable Player award in the name of Orlando Ramírez. In September 2009, he became one of the initial inductees in the Colombian Baseball Hall of Fame.

Orlando Ramírez Leal was born on December 18, 1951.[2] Miguel Ramírez and his wife, Raquel Leal, had 12 children in all. Little Orlando began to play baseball in his local neighborhood, Pie de la Popa, at the age of eight. He and his friends used balls of cloth and bats of cañabrava, a giant woody reed. As he grew up, he learned from his father, who was also a ballplayer. Orlando’s Angels teammate and translator, Winston Llenas, said in 1975, “His father played baseball with him every day. He said his father taught him the fundamentals…how to slide…throw…and catch. His father taught him a lot.”[3]

In Colombia’s first professional league, which lasted from 1948 to 1958, Miguel Ramírez (also known as El Ñato) played shortstop. During the winter of 1955-56, he was with a club called the Willard Blues. The third baseman was an Orioles farmhand who later became one of the all-time greats at the hot corner: Brooks Robinson.[4]

Baseball had come to Colombia decades before – as early as the 1870s, by one account. According to Raúl Porto Cabrales, the premier historian of Colombian baseball, it definitely reached Cartagena in 1897.[5] The sport took root along the nation’s Caribbean coast in the early 1900s and continued to gain popularity in the first half of the 20th century. For a synopsis, see Milton Jamail’s book Venezuelan Bust, Baseball Boom, which was informed by Jamail’s meeting with Raúl Porto.

Colombia was also active in international amateur ball. The national team took part in the Amateur World Series (now known as the Baseball World Cup) for the first time in 1944. They entered each of the seven subsequent tournaments from 1945 through 1953. In 1947, the ninth edition took place in Barranquilla, the other major city along the nation’s Caribbean coast. The host team – which included Miguel Ramírez – won (as they had in the 1946 Central American and Caribbean Games, also held in Barranquilla). The Amateur World Series did not take place again until 1961. Colombia did not participate that year, but won the next tourney in 1965; Cartagena was the host city.

Ramírez – who had served as an altar boy and errand boy when he wasn’t playing baseball – reached the top level of Colombian ball with the Willard club in 1966, just a week after his father died. A local star named Antonio “Manía” Torres, who had played professionally in Nicaragua, took Orlando under his wing. The speedy young shortstop played with various other club teams over the next few years. In 1969, aged 17, he made his debut with the Colombian national team as the Amateur World Series came to Santo Domingo. He hit third and played third base.

In 1970, the Amateur World Series returned to Cartagena, and Ramírez moved to shortstop and the top of the lineup. He led all players in stolen bases with eight. Orlando and Team Colombia also took part in the Bolivarian Games that December in the Venezuelan city of Maracaibo.

At the 1971 Amateur World Series in Havana, Ramírez helped Colombia to a silver medal by swiping seven bases, again the best in the tournament. That year Ramírez also led his team to victory in the Torneo de la Amistad (Friendship Tourney), held in Managua, Nicaragua. In addition, Colombia – hosting in the city of Cali – took the bronze medal at the 1971 Pan-American Games. The shortstop was later described as “a sensation.”[6]

The manager of the Colombian team in 1970 was Carlos Manuel Santiago, a Puerto Rican who had played in the Negro Leagues, the U.S. minors, and various other nations. Santiago was also an Angels scout. He signed Ramírez on March 15, 1972. The money wasn’t big: a sliding bonus that started at $5,000 with increments of $5,000 for reaching Double-A and Triple-A within 90 days. Still, it was way better than the 1,000 Colombian pesos a month – then a little less than US$50 – Orlando was making as an assistant mechanic for the local port authority, Colpuertos. The level of competition was also higher than the industrial league in which Colpuertos fielded a team.

Young Ramírez got a 90-day leave of absence from Colpuertos, during which the company held his job open in case he didn’t make it in the U.S., as everyone was warning him. At the time, he did not speak a word of English. His first pro season was also an odd reverse progression. He was initially assigned to Triple-A Salt Lake City, but before he played a game there, he went to Shreveport in the Texas League (Double A). There he went just 6 for 61 (.098) in 30 games, but that included his first pro home run. In mid-June, Orlando was sent to Idaho Falls in the Pioneer Rookie League. The Idaho Falls Post-Register wrote, “the shortstop just needs to work on his hitting…he can hope to go higher in the Angels organization…he could make it just on the quality of his fielding.”[7]

Indeed, despite the cultural obstacles and his mild hitting (.125-0-6 in 35 games for Idaho Falls), Orlando moved up quickly in the minors. El Ñato spent the 1973 season with Quad Cities of the Midwest League (Class A). He hit respectably enough (.260-3-45) and so he climbed back to Double-A El Paso to start 1974. Although his batting fell off to .194-0-20, he nonetheless reached Salt Lake City in mid-June.

Just a few weeks later, he made his big-league debut. Dick Williams had replaced Bobby Winkles as manager on July 1, and as part of his rebuilding effort, he decided to give some young minor-leaguers a look. Williams shifted Dave Chalk from short to third base and called up Ramírez, who got the news in a Tacoma hospital where he had been treated for a beaning.[8] He started and batted ninth at Anaheim Stadium on July 6. Two days later, the Angels sold veteran Sandy Alomar Sr., who had been sent to welcome Ramírez upon his arrival. Orlando remembered going to Alomar’s home for lunch and meeting his sons Sandy Jr. and Roberto, then aged eight and six.

Reporters informed Ramírez (erroneously) that he was the first Colombian to make the majors, which was also the reason he was issued the uniform number 1. Several articles then quoted Orlando as saying, “This makes my country and my family very proud.” He then quipped, “They might build a statue of me and put it next to the one of Simon Bolivar,” the revolutionary hero of several South American nations. The only paper that seemed to realize the rookie had tongue in cheek, though, was the New York Times.[9]

Actually, the first player born in Colombia to reach the majors was Louis Castro, in 1902. He was the first Latin American in the modern era, for that matter. However, as Brian McKenna detailed in his biography for the SABR BioProject, Castro moved to New York in 1885 at the age of eight. He learned baseball while attending Manhattan College High School. Indeed, for many years conflicting stories clouded this man’s origins. In 1976, Ramírez himself said, “My people tell me Castro wasn’t a Colombian. They think he was a Panamanian who lived in Colombia for a few years.”[10] Note also that Panama was part of Colombia until 1903, but that aside, Castro was born in the city of Medellín.

Ramírez started 20 games before he was sent back to Salt Lake. On July 22, the Los Angeles Times had written that the Angels “felt that Orlando Ramirez was not ready for the American League but the rookie shortstop has earned a longer look. He has been making the plays and his hitting has been acceptable.”[11] Before the month was out, though, California decided to move Dave Chalk back to shortstop. They called up Rudy Meoli and put him at third. Bobby Valentine, whose badly broken leg the previous year derailed his career, also saw action at short.

Ramírez hit for his best average as a pro at Triple A in 1974, .337 in 214 at-bats. When the rosters expanded that September, he returned and started another 11 games. After the season, the president of Colombia, Alfonso López Michelsen, sent Ramírez a telegram of congratulations.[12] The good feeling was regional; Nicaraguan baseball historian Tito Rondón said, “He was a morale builder for the part of the Caribbean that had no pro leagues at the time. Both Colombia and Nicaragua come to mind.” (By that time, Panama’s winter league was also defunct.)

In the winter of 1974-75, Ramírez went to play in the Venezuelan League. He got into just 11 games with Águilas del Zulia, hitting .294 with 2 RBIs in 34 at-bats. The regular shortstop was a Venezuelan native, César Gutiérrez, then in his fifteenth season at home. Venezuela made sense for Ramírez because its league was the closest to his homeland, but that was the only winter he played there. He wasn’t happy with the pay and left, and when he had a chance to play with the Caracas Leones, Zulia blocked him.

Ramírez made the Angels out of spring training in 1975. California was committed to having Dave Chalk play third, and it was the only position he occupied that year. The Colombian got off to a solid start with the bat; as of May 8 he was hitting .304. Coach Grover Resinger got credit for helping with Orlando’s mental approach. Winston Llenas said, “Grover has the right attitude toward Latin American players. He’s especially good with young players.”[13]

El Ñato’s high point in the majors came on April 29, when he got four hits in five at-bats at Royals Stadium and started three double plays. He said, “I felt out of place when the Angels brought me up. Now I feel relaxed. Oh boy, do I feel relaxed. I know I can play baseball, and I know can help this club.” Dick Williams, who called Orlando one of his “rabbits,” said, “I’d have loved to have seen Ramirez get the fifth [hit]. He’s a big key to our ball club. He has outstanding lateral movement. If the other team hits the ball on the ground, we’ve got an outstanding chance to get ’em out with Ramirez and our second baseman, Jerry Remy.”[14] Yet despite his “slick-fielding” rep,[15] Orlando committed 16 errors in 41 games in 1975, for a .905 fielding percentage.

The Colombian also ran into hard luck. “He pulled a hamstring on May 8. Before he could recover, he caught the chicken pox. Within a short time he had to return to Colombia to attend the funeral of a brother, who was killed in an airplane crash. Visa problems delayed his return and he finally was sent to Salt Lake City [in July] to play his way into shape. Ramirez’ luck – all bad – continued. He suffered a rib injury and wound up hitting only .197 for the Gulls.”[16] Billy Smith played most of May and June at short for California, but after Smith was found wanting, Mike Miley started for the remainder of the year.

During the winter of 1975, Ramírez lived with a family named Crawford in Garden Grove, California. He studied English at school and also with his host family, learning from TV news and even “Sesame Street.” As the 1976 season began, he still had the good will of Dick Williams, who said, “Shortstop is the key to the whole club. I want one guy to be the regular at shortstop. I don’t want to platoon. And I don’t want to move Dave Chalk over from third base.” He added of Orlando, “He feels more sure of himself. That’s the important thing.”[17]

Much the same pattern was visible in 1976. Again Ramírez was the starting shortstop on Opening Day, but this time the Angels gave him only until mid-May before shipping him back to Triple A. Dave Chalk did have to move back over again; California also obtained Mario Guerrero in May. Meanwhile, Orlando suffered yet more bad luck. He missed nearly two months following a freak accident that took place at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on May 17.[18] He “had doctors baffled with a mysterious injury after being hit on the chest with a ball while sitting in the dugout.”[19] He played just eight games at Salt Lake and finished the season back in El Paso.

Ramírez played with the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis in the Mexican Pacific League (LMP) in the winter of 1976-77. Although full data are lacking, he played several more seasons in the LMP, with Culiacán, Tijuana, and Mexicali. He recalled a number of appearances in league all-star games.

Ramírez spent his only full season in the majors in 1977. The Angels had signed Bobby Grich as a free agent to be their shortstop in November 1976, but a backup spot was open, especially after Mike Miley died in a car crash that January. When a back injury sidelined Grich for the year in early June, rookie Rance Mulliniks stepped into the revolving door. Orlando played very sparingly, getting into just 22 games with 13 at-bats through July 13. His main role was pinch-runner. Torn ligaments in his thumb then landed him on the disabled list until September, when he made three more pinch-running appearances.

Ramírez spent his only full season in the majors in 1977. The Angels had signed Bobby Grich as a free agent to be their shortstop in November 1976, but a backup spot was open, especially after Mike Miley died in a car crash that January. When a back injury sidelined Grich for the year in early June, rookie Rance Mulliniks stepped into the revolving door. Orlando played very sparingly, getting into just 22 games with 13 at-bats through July 13. His main role was pinch-runner. Torn ligaments in his thumb then landed him on the disabled list until September, when he made three more pinch-running appearances.

El Ñato did not see any big-league action in 1978, playing 99 games for El Paso and just six for Salt Lake City. He made the big club again to start the 1979 season, thanks in part to neighborly Rod Carew, who had arrived in a trade that February. “Carew even asked to room with Orlando Ramirez, one of those in the running for the Angels’ open shortstop job. Ramirez is from Colombia, and Carew, a native of Panama, felt he might be able to help Ramirez develop.”[20] Bobby Grich had moved to second base, and while Dave Chalk was still on hand, Rance Mulliniks won a three-way competition in spring training with Ramírez and Jim Anderson.

Orlando appeared in 13 games, including a hitless seven-game trial as the starter in late April and early May. On May 4, the Angels traded Chalk for 37-year-old Bert Campaneris; later that month they called up Dickie Thon to start his big-league career. California assigned Ramírez outright to Salt Lake City. He spent 27 games there, plus four with Charleston in the Houston Astros chain (likely on loan). His pro career in the U.S. then ended with an ignoble demotion to Bakersfield in the Class A California League.

The Angels released Ramírez in April 1980. He then played three summers in the Mexican League with the Chihuahua Dorados. In total, he hit 13 homers, drove in 107 runs, and batted .306; he was above .300 in each season. Orlando played for the North team in the Mexican League’s 1981 All-Star game. The Dorados finished poorly during this period, however, and the team folded after the 1982 season.

In the winter of 1980-81, Ramírez returned to Colombia. He played for Indios de Cartagena in the Colombian League, which had started up again in the winter of 1979-80 and lasted for seven seasons. Orlando’s playing career ended after the 1984-85 season, his fourth with Indios (he returned to Mexico for the winter of 1983-84). After a hiatus during the next two seasons, the second Colombian pro era ended in the winter of 1987-88.

Ramírez had several children with various women. One of them, Antonio Ramírez Vásquez, pitched in the Dominican Republic with the Montreal Expos organization in 1995. Orlando also had one daughter with a woman named Alma Rosa Gutiérrez – sister of Joaquín “Jackie” Gutiérrez, the second Colombian-raised major-leaguer. A fellow shortstop from Cartagena, Jackie batted .237 in 356 games from 1983 through 1988. It would be 13 years before the next and most famous Colombian ballplayer came along: 2010 World Series MVP Édgar Rentería from Barranquilla. The Cabrera brothers from Cartagena, Orlando and Jolbert, followed in 1997 and 1998.

Ramírez was named coach of the national team in 1988 but moved on from this role after a short period to serve as an instructor at lower levels. When Colombian pro ball resumed once more in the winter of 1993-94, he went on to the coaching staff of various teams. As of January 1, 2009, he became administrator of Cartagena’s main ballpark, Estadio de Béisbol 11 de Noviembre.[21] This stadium seats 12,000, more than any other baseball facility in the nation. It is sometimes called “the temple of Colombian baseball,” and Orlando Ramírez is a most fitting and dedicated guardian of this tradition.

John Jairo Capella’s article (“Orlando ‘Ñato’ Ramírez, abriendo caminos”) was originally published on August 18, 2010 on his “Playball” blog at Colombia’s leading newspaper, El Tiempo of Bogotá. It may be found at http://www.eltiempo.com/blogs/playball/2010/08/orlando-nato-ramirez-abriendo-1.php.

Capella’s article drew in turn on “Orlando Ramírez, ‘El Ñato’” by Raúl Porto Cabrales, originally published on April 22, 1995 in El Periódico de Cartagena.

Continued thanks to SABR member Tito Rondón; Jesús Alberto Rubio (Mexican statistics).

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

www.newspaperarchive.com

Jamail, Milton H. Venezuelan Bust, Baseball Boom. Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

Porto Cabrales, Raúl. Historia del béisbol aficionado de Colombia. Instituto Distrital de Deporte y Recreación de Cartagena de Indias, 2000.

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005.

[1] Miller, Dick. “Ramirez Flashy Feather in Resinger’s Angel Hat.” The Sporting News, May 24, 1975: 20.

[2] Ramírez gave the date as September 18, 1951 in talking with Raúl Porto Cabrales.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Royals lay dozen.” Lawrence (Kansas) Journal-World, April 30, 1975: 16. The Sporting News also confirms Robinson’s presence in Colombia that winter.

[5] Porto Cabrales, Raúl. “El Béisbol es el deporte más antiguo en Colombia, Cartagena es la cuna.” Special to John Jairo Capella’s “Playball” blog, March 22, 2007.

[6] The Salt Lake Tribune, March 23, 1972.

[7] “New Faces Dot Angels Camp.” Idaho Falls Post-Register, June 20, 1972. “Angels Hold Public Workouts.” Idaho Falls Post-Register, June 22, 1972.

[8] Prugh, Jeff. “Angels Have New Look but Result Remains Same, 1-0.” Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1974: C1.

[9] “What They Are Saying.” New York Times, July 14, 1974.

[10] Miller, Dick. “Hustler Ramirez Polishes English, Pleases Angels.” The Sporting News, April 17, 1976: 25.

[11] Hafner, Dan. “Angels End Grand Tour with Win Over Orioles.” Los Angeles Times, July 22, 1974: D1.

[12] Miller, “Ramirez Flashy Feather in Resinger’s Angel Hat”

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Royals lay dozen.”

[15] Elderkin, Phil. “Change of pace Angels in need of repair.” Christian Science Monitor, July 17, 1974: 9.

[16] Miller, “Hustler Ramirez Polishes English, Pleases Angels”

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ingram, Bob. “3-way chain reaction on a bad throw.” El Paso Herald-Post, August 5, 1976.

[19] Miller, Dick. “Two Pea-in-Pod Angels Reaping Harvest.” The Sporting News, August 21, 1976: 22.

[20] Gonring, Mike. “A Laid Back California Swinger.” Milwaukee Journal, March 15, 1979: Sports-2.

[21] Armenteros D., Ernesto. “Orlando “Ñato” Ramírez, administrador grandes ligas.” El Universal (Cartagena, Colombia), May 3, 2010. Note: On November 11, 1811, Cartagena became the first part of Colombia to declare independence from Spain.

Full Name

Orlando Ramirez Leal

Born

December 18, 1951 at Cartagena, Bolivar (Colombia)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.