Ovid Nicholson

Ovid Nicholson’s chief baseball skills were bunting and speedy base running. In 1912, he stole 111 bases in 123 games, vaulting from Class-D ball to a six-game stint in the majors.

Ovid Nicholson’s chief baseball skills were bunting and speedy base running. In 1912, he stole 111 bases in 123 games, vaulting from Class-D ball to a six-game stint in the majors.

A contributor to the SABR/Baseball-Reference Encyclopedia quite reasonably posed the question as to what else Nicholson could have done to win a job with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1912. He hit .455 during his two weeks with the team and made eight putouts with no errors in left field. The answer, unfortunately for Nicholson, was that the Pirates already had a regular left fielder in future Hall of Famer Max Carey, 22 years old at the time and showing great promise. Veterans Mike Donlin and Chief Wilson had joined Carey in the outfield that year. All three batted over .300, and Wilson set his probably unbreakable record of 36 triples in a season.

Nicholson played for Louisville and Nashville in 1913, the first of five more years of minor-league ball. In the 1920s, he managed for two-plus seasons in the Michigan State League. After baseball, he pursued a number of occupations — but it was clear that baseball was the career in which he had taken the most pride.

Ovid Edward Nicholson was born in Salem, Indiana, on December 30, 1888. He was the third of four children born to a farming couple, Indiana natives Joel D. and Effie M. Nicholson. The 1900 census shows the four children as Mabel (18), William (15), Ovid (13), and Margy (5). The family was well-enough off that they retained two servants, Fred and Bessie Spurgun.1Salem is the seat of Washington County in southern Indiana, about 30 miles from the northern border of Kentucky. The 1890 census enumerated a population of 1,974, up more than 20 percent for the second decade in succession.

Ovid’s brother William left school after the eighth grade and went on to become noted banjo player W. J. Nicholson of Nicholson’s Players. Music scholar Tony Russell writes, “In late January 1930, while much of the Midwest shivered in sub-zero temperatures, a group of men traveled some 150 miles to the Starr Piano Company’s studio in Richmond, Indiana. There they proceeded, over two days, to make eight recordings, employing various combinations of instruments—fiddle, harmonica, banjo, guitar, jew’s harp, and jug. Several of these recordings were first issued on Starr’s Gennett label, credited to ‘Nicholson’s Players.’”2 William Jefferson remained living at the family home in Salem, living with his mother.3 He never married and died in January 1958.

As of the 1910 census, William was listed as “musician” and his younger brother Ovid as “ball player.” Ovid Nicholson went just a bit further in his formal education than had William, completing his second year of high school. He had a passion and talent for baseball, however. And can be found in early 1909 under contract to the Springfield, Illinois, club.4 He didn’t make the squad, though, and was released on March 24, “back to the pumpkin patches.”5

An advertisement in The Sporting News apparently opened up a career in baseball for him. The story was told in his obituary. He saw an ad for players which had been taken out by the Great Bend, Kansas, baseball team. “Although his experience was virtually nil, he reported to the team and handily made the squad. It wasn’t long before his speed and desire made him well known.”6

He first turned up in baseball’s historical record in 1910, playing in Kansas for the Great Bend Millers of the Class D Kansas State League. The team won half its games (55-55) and finished fourth in the eight-team league.7 Nicholson, an outfielder who batted left-handed but threw with his right arm, appeared in 92 games, batting .254 (which ranked him third on the team). He had 17 extra-base hits, 11 doubles and 6 triples.

In 1911, Nicholson remained in Class-D ball, playing in 117 games for the Blue Grass League’s Frankfort Statesmen in the capital city of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He improved his batting average to .315 and hit his first home run. He hit 19 doubles and tripled four times. The team finished fifth in the six-team circuit. After the end of the season, he was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates.8 The Pirates, “disposing of the youngsters who will not be needed for the present,” sold his contract on January 25 to the Springfield, Ohio, club.9

Somehow, he wound up back in Frankfort. The renamed Frankfort Lawmakers won the 1912 pennant, four games ahead of Maysville, with a record of 85-42. The “discard,” Nicholson, led the Blue Grass League in base hits (178), runs scored (128), and stolen bases (an incredible 111). The Sporting News took note of “the remarkable base stealing of Nicholson of Frankfort, who set a mark of 111 pilfers in 123 games. The nearest rival was Langenham of Maysville, who stole 54 in 78 games, which would be noteworthy itself but for the overshadowing work of Nicholson.”10 The publication noted that Nicholson had scored more runs than games in which he played.

After Frankfort’s season was over, it is perhaps not surprising that he got the call to come to Pittsburgh — a leap from Class D to the major leagues.

His debut for the Pirates and manager Fred Clarke came on September 17 in a game in Brooklyn. He was inserted as a pinch-runner, but did not score. The following day, Clarke gave Mike Donlin a rest and Nicholson played left field in the second game of a Wednesday doubleheader in Boston against the Braves at the South End Grounds. He was 1-for-3 at the plate, with a single, batting third in the order. He struck out the other two times. His hit was just one of two recorded by Pirates batters in a game that ended due to darkness in a scoreless tie after eight innings. The Pirates had won the first game, 9-1. Nicholson had almost made the difference in the second game. In the third inning, Boston’s Lefty Tyler walked the leadoff batter, third baseman Bobby Byrne. Max Carey, playing center field, sacrificed Byrne to second base. Nicholson hit the ball to right field for a clean single. “Byrne set sail for the plate,” wrote the Boston Globe, but John Titus “made a perfect throw from deep field and [Braves catcher Bill] Rariden nipped Byrne as he came sliding in.”11

On September 19, the Braves hosted another doubleheader. Nicholson pinch-ran in the eighth inning of the first game. Again, he did not score; the Pirates lost, 7-5. He played the second game, again batting third and playing left field. He was 2-for-2, with a sacrifice in his other plate appearance, and scored his first run. The Pirates won by one run, 8-7, another eight-inning game. With two outs in the first inning, he singled. Both shortstop Honus Wagner and first baseman Dots Miller singled as well, and the Pirates had their first run. In the third inning, Carey singled, Nicholson sacrificed him to second, and Wagner singled for Pittsburgh’s second run. Though he added another single his next time up, he was pinch-hit for in the sixth inning.

Wrapping up the visit to Boston, the Pirates won again on Friday the 20th. Nicholson collected his first (and only) run batted in. He was 2-for-4, earned a base on balls in the fourth inning, and scored after Wagner doubled and Dots Miller hit a grounder on which he scored, the throw to Rariden at the plate proving unsuccessful. Pittsburgh scored eight runs in the inning; his second time up, Nicholson singled but was left on first when Wagner flied out to Rabbit Maranville at short. The Pirates were victors, 10-2.

It was an exceptionally cold day and only 300 fans turned out. The full nine-inning game was played in one hour and 15 minutes. Seven of Nicholson’s eight putouts as a Pirate came in this game, and James C. O’Leary of the Boston Globe singled him out for praise: “Nicholson of the visitors played a fine left field. . .some being on difficult chances.”12

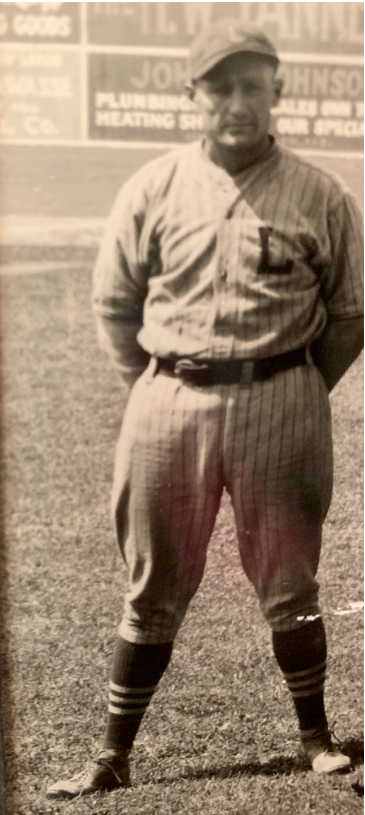

The Pittsburgh Daily Post featured him with a photograph on page 13 of their September 24 edition. On the morning of the 25th, the Pittsburgh Press wrote, “Pittsburghers may get a chance to see Ovid Nicholson in action, for it is probable that the young speed wonder of the Blue Grass League will be given a further tryout before the season closes. He was a marvel at base stealing in Kentucky, and those who have seen him in the big show declare he will keep up the pace. He looks like a natural ballplayer.”13

The only other game Nicholson played in the majors was on September 26, at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. He was 0-for-2 but the Pirates won nevertheless, 7-5, over the Cardinals. The Press was not that impressed: “The young man did not have much of a chance to show what he could do, for he was removed to allow [Claude] Hendrix to bat in the sixth inning, and [Ed] Mensor replaced him.”14

Because he never played in the big leagues again, Nicholson’s final on-base percentage was an even .500. All five of his base hits were singles; he scored two runs. The Press account of his final game continued, “He is a well-built chap, and seems to have a lot of strength but he showed ignorance of the game yesterday, which is but natural, as he has never had much experience, and then only in the bushes.”15 He stood 5-feet-9 and was listed at 155 pounds.

After the season was over, Nicholson’s contract was sold to Louisville. An assessment in The Sporting News said, “Nicholson is speedy as a streak. He is said to be a light sticker, but able to beat out many infield taps.”16 Looking at Pirates stats for 1913, one wonders if there might have been room in the outfield for him. Donlin did not play in the majors that year. Rookie Everette Booe, also known for speed, proved to be a flash in the pan. Pittsburgh used assorted other veterans — even 40-year-old skipper Clarke played in nine games.

Nicholson is shown with three teams in 1913: he began the season with the Double-A American Association Louisville Colonels, was optioned to Nashville briefly in late May, then returned. In all, he batted .262 in 32 games for Louisville, ultimately spending most of the season (as of July 11) with the Class A Wichita Jobbers of the Western League (82 games, .315). Wichita finished in last place.

In 1914 and 1915, Nicholson played with Wichita. In spring training 1914, the Wichita Beacon noted his talent for getting on base by bunting: “Ovid Nicholson, the buntin’ kid, is the guy who’s supposed to put the runner on second, and if anyone can do it and then get a base knock by beating the ball to first, Ovie is the one to place a bet on. We need not spend any time tuning our lyre and singing Nicholson’s praise. All of the fans know what he can do, and they are as strong for him as a barrel of onions.”17 A game on August 17 was indicative of his particular skill; he was 2-for-5 against Topeka, both base hits secured by beating out bunts.

In 154 games, he hit for a .305 average in 1914 and recorded 60 stolen bases, the team again finishing in last place. On May 9, in a game against Topeka, he hit an inside-the-park home run, one of only two homers in 1914.18 His only other one came the very next day, hit over the right field fence.

In mid-July, the Topeka State Journal suggested a reason he’d not been brought back to the big leagues: “his disposition.” The paper wrote, “Nick is a consistent three hundred hitter and is as fast on his feet as any man in the big yard. Nick is inclined to sulk when things are breaking bad, otherwise he might now be under the big tent.”19

Statistics for 1915 are not available, but after being quarantined with measles for most of spring training and suffering a badly sprained ankle in mid-June, he appears to have played in 115 games, between Wichita and St. Joseph, and stolen 25 bases. He was traded to St. Joseph on June 8.20 In 1915, Wichita finished in seventh place, with St. Joseph last.

St. Joseph sold Nicholson’s contract to Chattanooga on April 1, 1916. He played in 11 games for the Southern Association (Class A) Chattanooga Lookouts (with a disappointing .154). He was released outright on April 27. The conclusion drawn by the New Orleans Item: “Big league scouts all fell for his speed, though they found him deficient in some other particulars.”21

As a free agent, he signed a one-year contract with the Hannibal Mules and played in 102 games in the Class B Three-I League. There he hit .275, but a twisted knee in mid-August put an end to his season.

In 1917, he remained in the Three-I League but signed with the Quincy Gems. He hit .262 in 66 games. He may have been on the move. A newspaper report in July indicates that he was purchased by the Sioux City Indians, acquired from Bloomington.22 How much or how little he may have played with them is unclear. It appears to be the last year in which he played baseball.

On January 7, 1918, Nicholson married Nellie Donica. Her father Williams had been a farm laborer in Marshall, Indiana, later becoming a janitor in the courthouse at Bedford, Indiana. Nicholson no doubt had met Nellie through baseball; her brother Harry was a shortstop and third baseman on the 1912 Frankfurt team. In 1916, they both played ball in the Three-I League, albeit for different teams. Harry Donica played for Bloomington in part of 1914 and all of 1915 and 1916.

In January 1918, Nicholson enlisted in the U.S. Army and began taking instruction at an aviation school in Kenosha, Wisconsin.23

It appears that at some point, perhaps in late 1918, he played ball in Canada.24 In early 1919, he was said to be reporting to the Kitchener team in the Michigan-Ontario League.25 On May 14, in the final exhibition game of spring training, however, he injured his leg and proved unable to play on Opening Day.26

The 1920 census shows the Nicholsons living in Kenosha, with Ovid working as a machinist for an automobile company there.

There was a gap of some years, though he is seen in the Kenosha city directory as a mechanic in 1921. A 1922 article reported him as manager “of the Sterling team” of Pontiac, Illinois.27 He was released by Pontiac in late August.28

A Battle Creek resident in 1926, he was hired to manage the Ludington (Michigan) Tars. The team had been in the Central League to start the season, but that league merged with the Michigan-Ontario League in mid-June and formed the Michigan State League (Class-B). Nicholson played some left field with the team and earned a reputation as a good manager. The July 6 Ludington newspaper wrote, “Nicholson is being given great credit by the fans who make a study of the game for his judgement in shifting pitchers and general managerial ability.”29 He was said to have played the field well and had more than one multi-hit game. He hit .269 for the season and was 3-for-3 in the team’s final home game.30 The Tars finished fifth of eight teams with a 45-51 record. Nicholson may have played in a small number of games but so few that he does not turn up in the record. How he had maintained contact with baseball, why he was chosen, and why he never appears in the baseball record again all remain open questions. He clearly retained an affinity with the game, and identified as a ballplayer. After his death in 1968, his surviving widow Nellie listed his occupation as “retired ball player.”

The 1930 and 1940 censuses both show him in Kenosha. He was listed as a “professional” in the athletic industry in 1930 but in 1940 both Nellie and Ovid seem to have become involved in retail clothing. He was listed as a salesman of men’s clothing. She was listed as manager of what appears to be a ladies’ ready-to-wear retail firm. The city directories of 1931 and 1935 show him as “auto worker” and “clerk, J.C. Penney.” In 1941, he was listed as a salesman, and at the time of his registration for the Second World War draft as an employee of Holly Style Stores of New York City, based in Kenosha. A 1945 newspaper clipping identified him as the “legal representative” in this district for Holly Style Stores and indicated his plan to have a new store built in downtown Racine.31

In 1947 he was the assistant manager of the Holly Shop on 8th Avenue in Kenosha. In 1953, Nicholson retired from the retail firm and both he and Nellie moved back to Salem.32 He attended the First Christian Church, was noted as a World War I veteran, and “a member of several conservation clubs, and was fond of hunting, fishing, and antique collecting.”33

That is where they were living at the time of Ovid’s death of a cerebral thrombosis on March 24, 1968. He had been stricken 10 days earlier, and died in Washington County Memorial Hospital. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Salem. He was survived by his wife and his sister, Margie Mooney of Cincinnati. Nellie died on December 23, 1989, of pneumonia. She had become the manager of a ladies clothing chain.34 The couple had one daughter, Donna Rose Nicholson (born June 15, 1922) who predeceased them both, dying in Ludington, Michigan, from infections primarily caused by staphylococcus, two weeks to the day after she turned 4 years old.35

Acknowledgments

Thanks to British music historian Tony Russell for inspiring me to take on this biography. He had written about W. J. Nicholson’s career as a banjo player, and during a luncheon in London the day after the Yankees and Red Sox had played there in June 2019, Tony mentioned that there was a Nicholson in the family who had played major league baseball. My curiosity was piqued.

Thanks to Kathy Knight-Wade of the John Hay Center in Washington County, Indiana, and to SABR members Alan Florjancic of Kenosha and Dr. Henry Berman. Thanks to Bill Anderson of SABR as well, author of the 1992 publication The Ludington Mariners: Minor League Baseball in a Maritime Community.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Nicholson’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 The precise ages of the children don’t always seem to match up with given birthdates, but their relative ages and the spread between them remains consistent. The two servants were listed as “W” (white); the correct spelling of their surname is almost certainly Spurgeon. Fred was listed as a “farm laborer” in the 1900 census.

2 Tony Russell, “Nicholson’s Players.” Old-Time Herald 13: 5 (March 2013): 28–35. It is of note that another Spurgeon, Archie Green Spurgeon, was guitarist for Nicholson’s Players.

3 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses.

4 “Kinsella Reveals List of Players,” Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), March 6, 1909: 8.

5 “Pickups on the Radiator Circuit,” Daily Review (Decatur, Illinois), March 25, 1909: 5.

6 “Former Big-League Ball Player Dies,” County Press (Washington County, Indiana), September 19, 1968.

7 These figures are per Baseball-Reference.com in 2019; the 2007 Encyclopedia of Minor-League Baseball has the team 54-55 and in fifth place.

8 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Prophets Can’t See Pittsburg,” Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield, Illinois), February 4, 1912: 2.

9 “Clarke Reduces Corsair Roster By Two Discards,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, January 26, 1912: 9.

10 “A Hitter’s Heaven,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1912: 8. Nicholson had not set a minor-league record, although even decades later some newspapers later reported it as such. In 1913, James Johnston of the San Francisco Seals stole 124 bases.

11 “Pirates Gather In One, Tie Other,” Boston Globe, September 19, 1912: 5.

12 James C. O’Leary, “Tessie Fails to Work This Time,” Boston Globe, September 21, 1912: 6.

13 “Clarke’s Pirates at Home,” Pittsburgh Press, September 25, 1912: 14.

14 Ralph S. Davis, “Babe Adams May Oppose Cardinals,” Pittsburgh Press, September 27, 1912: 26.

15 Davis, “Babe Adams May Oppose Cardinals.”

16 “Louisville Loses Loudermilk,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1912: 15. The Lexington Leader called Nicholson “the speediest fielder and base-runner ever developed in the Blue Grass League.” “Review of the Week’s Sports,” Lexington Leader (Lexington, Kentucky), December 15, 1912: 24.

17 “Jobbers’ Showing Pleased the Fans,” Wichita Beacon, March 23, 1914: 7.

18 “Witches Secure Another,” Wichita Daily Eagle, May 10, 1914: 7.

19 “Gossip of Sports,” Topeka Daily State Journal, July 24, 1914: 4.

20 “Managers Involved in Western League Trad; Also 5 Men,” Albuquerque Morning Journal, June 9, 1915: 9.

21 It was the Item, which reported the 25 stolen bases in 1915. Ham, “Fastest Man in Baseball Fails to Stick in Southern,” New Orleans Item, April 27, 1916: 12.

22 “‘No-Hit’ Pitcher Signed,” Sioux City Journal, July 15, 1917: 14.

23 Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas), June 13, 1918: 3.

24 “Newsy Gossip for Baseball Fans,” Bay City Times (Bay City, Michigan), April 10, 1919: 12.

25 “Speed Is What Kitchener Wants,” Bay City Times (Bay City, Michigan), April 19, 1919: 12.

26 “Wet Grounds Spoil Finale with Red Sox,” Saginaw News, May 17, 1919: 8.

27 Frank Newhouse, “Double Bill Sunday at Elitch’s Gardens; Games at Broadway,” Denver Post, May 7, 1922: 10.

28 “Pontiac Releases Trio,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1922: 12.

29 Ludington Daily News, July 6, 1926: 2.

30 Ludington Daily News, September 5, 1926: 6.

31 “A ‘Face-Lifting’ Promised for Main St. Area,” Racine Journal-Times, August 7, 1945: 1.

32 “Former Big-League Ball Player Dies.”

33 Ibid.

34 See obituaries for Ovid Nicholson and Nellie Nicholson. Her obituary is “Nellie Nicholson,” Salem Leader, December 1989.

35 Death certificate, Michigan Department of Health. Thanks to Dr. Henry Berman.

Full Name

Ovid Edward Nicholson

Born

December 30, 1888 at Salem, IN (USA)

Died

March 24, 1968 at Salem, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.