Pete Van Wieren

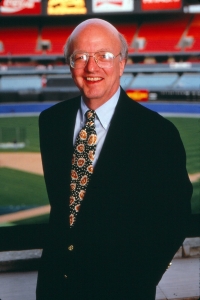

Skip and Pete. Two names forever etched in the history of the Atlanta Braves and in the history of baseball on television. Just the mention of their names brings back warm memories and a smile to many baseball fans, and not just those in Atlanta. Rarely is one of them ever mentioned without the other also being mentioned. For 33 years, from abysmal records to a miraculous revival and the formation of a dynasty, the voices of Skip Caray and Pete Van Wieren narrated the story of the Atlanta Braves on radio and television. They had very different styles, but their chemistry resulted in a lifetime of memories. “With his thick glasses and thinning hair, Van Wieren didn’t fit the classic television mold,” wrote Paul Newberry in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “But his soothing voice and ability to come up with obscure statistics in the pre-Internet era paired well with Caray, who was known for his biting sarcasm and witty retorts.”1 With the advent of cable TV, Skip and Pete gained a following of millions of fans around the country who either had no major-league team in their market or could only rarely see their home team on television. The Braves acquired the nickname “Team of the 90s” through this national exposure, and Skip and Pete were the main voices they heard describing this dynasty. Van Wieren was dubbed “The Professor” due to a physical likeness to another with the same nickname, but his thorough study and preparation for each game qualified him to inherit the name on its own.

Skip and Pete. Two names forever etched in the history of the Atlanta Braves and in the history of baseball on television. Just the mention of their names brings back warm memories and a smile to many baseball fans, and not just those in Atlanta. Rarely is one of them ever mentioned without the other also being mentioned. For 33 years, from abysmal records to a miraculous revival and the formation of a dynasty, the voices of Skip Caray and Pete Van Wieren narrated the story of the Atlanta Braves on radio and television. They had very different styles, but their chemistry resulted in a lifetime of memories. “With his thick glasses and thinning hair, Van Wieren didn’t fit the classic television mold,” wrote Paul Newberry in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “But his soothing voice and ability to come up with obscure statistics in the pre-Internet era paired well with Caray, who was known for his biting sarcasm and witty retorts.”1 With the advent of cable TV, Skip and Pete gained a following of millions of fans around the country who either had no major-league team in their market or could only rarely see their home team on television. The Braves acquired the nickname “Team of the 90s” through this national exposure, and Skip and Pete were the main voices they heard describing this dynasty. Van Wieren was dubbed “The Professor” due to a physical likeness to another with the same nickname, but his thorough study and preparation for each game qualified him to inherit the name on its own.

Peter Dirk Van Wieren was born on October 7, 1944, in Rochester, New York, to Howard and Ruth (Jardine) Van Wieren. He grew up in the nearby blue-collar suburb of Greece in a home owned by his maternal grandparents, Wilbur and Eunice Jardine. “It was a typical Leave It to Beaver neighborhood,” he recalled, “except folks went to work carrying lunch boxes, not briefcases.”2 His aunt, Helen Jardine, also lived with them.

Baseball was always a part of Pete’s life from the very beginning. He grew up a fan of the Rochester Red Wings of the Triple-A International League, a farm club of the St. Louis Cardinals. Van Wieren remembered listening intently on the radio as Jack Buck and others called the Red Wings games on the radio. He also remembered the first professional game he attended, at Rochester on August 13, 1950, when Rochester and Jersey City played a 22-inning marathon before the home team prevailed, 3-2. “That game really got me hooked on the Red Wings,” he said. When he was at the ballpark, Pete would often glance up at the men whose voices he heard on the radio, Buck and other announcers, as they made their way to the press box.3 “The more I watched them,” Van Wieren said, “the more I wanted to someday do what they did.”4 Even as a boy, the young “professor” would analyze the Red Wings games, keeping a scrapbook and replaying the play-by-play of games in his driveway as he threw a rubber ball off the garage door. He would skip down to the local pharmacy and grab a copy of The Sporting News, which he read cover to cover by first grade.

Van Wieren had a large extended family, which would gather for birthdays and special occasions. The gatherings never included Pete’s father, however. Pete had been told that Howard had died in World War II. When Pete applied to Cornell University, he learned of a scholarship for children of deceased veterans. He had to provide basic information about his father which he couldn’t answer. He asked his school librarian at Rochester’s Charlotte High School for assistance. She pointed him to the public library, where he could look up the directory of World War II casualties. He couldn’t find his father’s name, so he asked his mother. Pete had uncovered a family secret.

Howard Van Wieren abandoned Ruth when she was pregnant with Pete. He was a truck driver for a Coca-Cola bottling company in Rochester. When he discovered her pregnancy, he disappeared, abandoning his truck and taking the money he had collected that day. A police investigation was unable to find Howard’s whereabouts. A couple of weeks after Pete was born, Howard called, asking about the newborn. The family sent him a bus ticket to come and visit young Pete. Ruth waited hours for Howard to arrive, but he never showed and instead sold his ticket for cash. No one in the Van Wieren family heard from Howard again.5

Pete enrolled at Cornell in 1961. “I rarely missed a sporting event,” he recalled, noting that he did other things in his free time. “I learned which taverns you could get into without proof of age — I was only 16, and the minimum drinking age in New York at that time was 18.”6 He also wrote for the campus newspaper, the Cornell Daily Sun, which led to freelance opportunities for the Baltimore Sun.7 Covering a Cornell-Scranton baseball game, Van Wieren met Harry Dorish, a former major-league pitcher now a scout for the Milwaukee Braves. Before the game, the engineer for the student radio station, WVBR, rushed in, exclaiming that his announcer couldn’t make it and he needed a replacement. “Go ahead, give it a try,” Dorish said to Van Wieren. “You might like it. It’s easier than writing.”8 Pete did, and took his first step into broadcasting.

While on campus, Van Wieren also became involved in a band called the Hustlers, named for the popular Paul Newman movie. They opened for Bo Diddley and performed with Chubby Checker, with Pete playing the drums. He also spent time investigating the mystery of his father. Howard’s parents, Joseph and Katherine Van Wieren, lived in nearby Buffalo. A visit to them brought only disappointment, however, as they had not heard from Howard in years. They rejected invitations he sent them to visit him at Cornell. “Years later, after both of them had died, we learned that they were both ashamed of what their son had done and fearful that we were seeking their financial help — which we were not,” Van Wieren wrote.9

With responsibilities at the newspaper and to the band, Van Wieren let his grades slip and he soon dropped out of Cornell. He married his girlfriend, Elaine Rosinus, who was working toward a teaching degree. The newlyweds moved to Washington where Pete’s mother was working as an office manager for Senator Kenneth Keating of New York. Pete got a job working for the Washington Post in merchandising and promotion. His first flyer promoted the legendary sportswriter Shirley Povich.

Van Wieren still had his dream of being a baseball broadcaster, so an ad he saw in the Post for the National Academy of Broadcasting piqued his interest. He began taking night classes at the school, where he learned to operate radio equipment. One class assignment sent him to the press box at Griffith Stadium to record his own broadcast of a Washington Senators-Chicago White Sox game. “I was sitting between the Chicago and Washington radio crews with my little tape recorder and hand mike and I kept thinking, ‘This is going to be great. I can see myself doing these things when I get my first job.’”10

Pete finished his courses in less than a year and was soon hired at WEER Radio in Warrenton, Virginia. Pete led the morning news and sports, worked as a disc jockey, and did sales as well as commercials. He remembered vividly his first sports assignment. “They told me to go out and cover a horse show,” he remembered a few years later. “I didn’t know anything about horses then and I don’t know much about it now. And to do it on radio! Well, it’s hard to talk to a horse. I ended up getting dressed in a nice suit to make a good impression. When I got there, it was raining and everything was covered with mud except all the people at the show who knew enough to wear boots and old clothes.”11 He also did the play-by-play of the Fauquier High School football team.

Van Wieren would be there just a few months, however, as the station manager in Manassas, Virginia, heard Pete’s work and offered him a job at radio station WPRW. He did play-by-play for high-school sports, Little League, and American Legion baseball. The press box at the football field would shake when the train rumbled by. “After one game I climbed down the 50 rickety ladder steps and mentioned how shaking the thing was,” he recalled. “The old wino who took care of the grounds looked up and said, ‘Yup. Couple more trains come by and the whole thing’ll go.’”12 Van Wieren was ready to move on and seek a professional baseball job, which he landed in September of 1966 at WNBF Radio in Binghamton, New York.13

The Binghamton Triplets were the Double-A affiliate of the New York Yankees but did not have any broadcasting coverage for lack of sponsors. Pete asked the station manager, “If I could sell them, could I do them?” He agreed, and Pete pulled double duty working on the radio from 3 P.M. to midnight, then would go out knocking on the doors of local businesses the next morning. His hard work paid off as sponsors put the Triplets on the air in 1967.14

The broadcasting rights moved to WINR for 1968, so Pete followed the team there. In those days, access to updated player statistics depended on a weekly mailing from the league office. Pete worked out a deal with the Binghamton Evening Press, which received daily box scores from wire reports but did not publish them because of space restrictions. Someone at the paper now saved these box scores and hung them on the wall in the sports department under the sign “Pete’s Peg.” Van Wieren would pick these up and compile statistical notebooks of each team, becoming the go-to information guru who was always up to date.15

Binghamton’s Press and Sun Bulletin advertised Van Wieren’s daily radio show on WINR on the same entertainment page that advertised Don Knotts and Perry Mason. “Tune to the big winner for Pete Van Wieren,” the ad hyped of the 10:30 A.M.-2 P.M. show. “Tune in for the best of all kinds of music … with time and weather checks all tied together with the bright thread of commentary that is Pete’s specialty.”16 Van Wieren’s duties included a Sunday Challenge Bowling program. “The extra $30 a week was well worth it, even if it meant interviewing one champion who had no teeth,” Pete joked.17

In 1969 the Triplets moved to Connecticut so Van Wieren relied on broadcasting high-school basketball and basketball games for Broome Tech, a local junior college. During a postgame interview at Broome, a janitor turned off the power and the gym lights. “We were stunned for a minute,” Pete said, “and I didn’t have any way to tell the station what had happened. Luckily, I had battery power to hook up and we got it going in a minute. The rest of the interview was done in a dark gym by the light of radio tubes.”18

In 1970 Van Wieren submitted a tape of a broadcast he did to the Yankees. The club was impressed with Pete but instead chose Bill White, the first African-American play-by-play announcer in baseball. The Van Wieren family was growing as sons Jon (1967) and Steven (1970) came along. Pete needed a stable income. He would have to become a weatherman to do it.19

Pete’s new job in 1972 was for a new ABC-TV affiliate in Toledo, Ohio. The station had such a strapped budget that Pete would have to give the weather forecast in addition to his sports anchor duties. He quickly tired of the double duty. As luck would have it, Van Wieren’s eye caught a story on the Associated Press wire. Marty Brennaman, the play-by-play announcer for the Tidewater Tides (Norfolk, Virginia) of the Triple-A International League, was leaving to begin his legendary career with the Cincinnati Reds. Pete immediately interviewed and became the new Tidewater play-by-play announcer for 1974, taking a salary cut from $18,000 to $10,000. He didn’t mind it, as now he could concentrate on his love of baseball while finding jobs on the side. He served as the team’s beat reporter for away games for the Norfolk Ledger-Star and also did play-by-play for the Virginia Red Wings hockey team of Norfolk for two seasons, calling games for the International League pennant winners in 1975.20

After the 1975 season, the Atlanta Braves fired announcer Milo Hamilton. Van Wieren applied and heard a life-changing phone call from Braves announcer Ernie Johnson. “How would you like to become part of the Braves’ broadcast team?” he asked. “You’ve got the job. Welcome to the family.” The Braves also had another new announcer: Skip Caray. The duo would become lifelong friends and spent the next three decades together in the booth. Caray had been broadcasting Atlanta Hawks basketball games since 1968. Johnson, Caray and Van Wieren covered both television and radio broadcasts. Ted Turner purchased the Braves franchise in January 1976, and baseball on the emerging industry of cable television would never be the same.21 “Skip was always off the wall,” Johnson remembered in 2004. “Took me a while to get used to it. You didn’t know quite what to say. I made the adjustment. Pete was very businesslike and talked like a professor, so we started calling him ‘The Professor.’ And if we ever needed any information, we’d say, ‘Go ask Pete.’ He kept such great records and stats.”22

“The whole thing is a dream come true for me,” Van Wieren told Larry Bump of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle shortly after the announcement. “I’ve tried for several jobs and gotten close a couple of times, but finally getting a job like this is something you never expect. I’ve never had any ambition further than reaching this level. Now, I’d like to keep the job for a while and develop the same kind of respect Vin Scully has among other broadcasters.”23 Van Wieren was starting to get comfortable with his new position, covering the Braves in spring training and into the first month of the season. The “Professor” sobriquet was bestowed on Van Wieren by Johnson because of Pete’s resemblance to former Reds pitcher Jim Brosnan, who also had the nickname for his scholarly appearance and the small library he traveled with on the road.24 Pete was known for his academic, scholarly approach to the game. “One of the things that made game preparation so enjoyable for me is my love of research,” he said. “I truly enjoy digging through old box scores, newspaper stories, record books, and magazines, hoping to hit on some interesting fact I never knew before. Whenever I could, I would share those findings with viewers and listeners.”25

Far from a scholarly approach was the temperamental nature of Ted Turner, the Braves owner. Turner called Van Wieren to his hotel room and asked him if he was accustomed to traveling while at Tidewater. Satisfied with Pete’s answers, Turner then called traveling secretary Donald Davidson’s room and told him he was fired. Davidson had been with the Braves since their Boston days, beginning as a 10-year-old batboy. Davidson, all of 4 feet and 85 pounds, had become a Braves institution, as pictures with Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Casey Stengel, and others revealed.26 “I felt very bad for Donald, who had treated me so well during my first months with the team,” Van Wieren wrote.27 So in addition to broadcasting, Pete would spend the day handling everything from hotels and plane tickets to buses and equipment trucks. He survived his first season with the Braves, who finished a dreadful 67-94, the first of five straight losing seasons. Perhaps the most notable event came in December when Turner made his cable television station, WTCG, available to other cable systems around the country via satellite. In a couple of years, WTCG would become WTBS (Turner Broadcasting System).28 The Braves would now be a national team.

Van Wieren saw historic and also bizarre moments with the Braves in the late ’70s. Turner himself managed the Braves for one game in 1977. In 1978 fans at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium saw Braves pitchers hold Pete Rose hitless to end his 44-game hitting streak. Van Wieren witnessed Phil Niekro’s 200th win and also the shocking death of Braves executive Bill Lucas.29 Handling two jobs was wearisome, however, and Pete considered leaving the Braves. One day a call came from Boston radio station WITS, which then carried the Red Sox games. Red Sox play-by-play man Ned Martin was moving to the TV booth. Pete considered the possibility, but WITS needed to boost its signal or risk losing the broadcasting rights in 1979.30 Pete decided to stay in Atlanta, but told Turner he was done being the traveling secretary and could now concentrate solely on broadcasting.

Van Wieren had even more opportunities as Turner’s new Cable News Network (CNN) debuted in 1980. Pete filled in on some weekend and late-night sports segments. When the players strike put the 1981 season on hold, Caray and Van Wieren passed the time by broadcasting the games of the Braves Triple-A club in Richmond, Virginia. When play resumed, ratings on TBS soared, and with Joe Torre as the new manager, the Braves became a legitimate contender.31 The team began the 1982 season 13-0 and went on to win the National League West before being swept by the Cardinals in the NLCS. “Despite the disappointing ending,” Van Wieren remembered, “the season was a spectacular success. TBS ratings soared. Sports Illustrated did an article on Braves fans in Storm Lake, Iowa; Valdez, Alaska; and Reno, Nevada. Our fan mail was pouring in from all over the world, and Braves fans were showing up in virtually every ballpark on the road.”32

The Braves success was short-lived, however, as they finished second in 1983 and 1984, then a pitiful fifth (66-96) in 1985. Three games over this time, however, were some of Van Wieren’s most memorable moments. The first was an August 12, 1984, game against San Diego that resulted in several brawls and the ejection of 13 players. The second was the July 4, 1985, game in Atlanta against the Mets. That contest went 19 innings and included over three hours of rain delays. In the 18th inning, with the Braves trailing 11-10, Atlanta pitcher Rick Camp hit a home run to keep the Braves alive. The Mets scored five off Camp in the top of the 19th and the Braves fell short, 16-13. The Fourth of July fireworks then began at 4 A.M. on July 5, frightening residents in the neighborhood. Another memorable moment was Bob Horner’s four-home-run game in 1986. “He did it! He did it!” the excited Van Wieren exclaimed after the fourth cleared the fence. “He becomes the 11th player in major-league history to hit four homers in one game. His name is in the record books.”33

TBS decided to add a fourth member to the broadcast booth, so Van Wieren, Caray, and Johnson were joined at times throughout the 1980s by Darrel Chaney, John Sterling, Billy Sample, and Don Sutton. Ernie Johnson retired after the 1989 season.

Bobby Cox, who managed the Braves from 1978 to 1981, returned as general manager, promising it would take five years to rebuild the club. Van Wieren described the 1986-1990 years as “one long losing season.”34 The club finished at or near the bottom of the NL West and averaged 96 losses per season. The team invested in scouting and player development, while acquiring players who would turn the franchise around in the next decade. Cox would return to the dugout and be a part of that remarkable era, which included names now synonymous with the Braves: John Smoltz, Tom Glavine, Chipper Jones, Mark Lemke, David Justice, Ron Gant, and others. The 1990s would be the decade of the Braves.

The 1991 season was remarkable as two teams, the Twins and Braves, went from worst the year before to best, facing each other in the World Series. This was the first of 14 consecutive seasons in which the Braves would win their division title. The Braves-Twins World Series was an instant classic, going all seven games and finishing with a 1-0 Minnesota victory in 10 innings. Van Wieren summed up the series from the radio booth: “The Minnesota Twins have won the World Series and may be the world champions, but the Atlanta Braves have won the hearts of baseball fans all over America.”35 Skip, Pete, and Sutton were included in the Braves’ parade after the Series before a crowd of 750,000. “We weren’t treated like we lost,” Van Wieren said. “It could not have been any better.”36

The 1992 Braves returned to the World Series in memorable fashion. The improbable Francisco Cabrera singled home a lumbering Sid Bream to beat the Pirates in the ninth inning of Game Seven of the NLCS, a classic moment of baseball history. Skip and Pete again covered the World Series on radio. The Braves lost again, this time to Toronto.

The addition of Greg Maddux on the mound and Fred McGriff at first propelled the Braves to 104 wins in 1993, the most in franchise history. Both the Braves and San Francisco (103-59) had hot seasons, with the Braves narrowly beating out the Giants for the division crown. But they weren’t any hotter than the night smoke started billowing out of the Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium press box, two booths from where Van Wieren and Caray had been preparing for the broadcast. Everyone was evacuated onto the field after an explosion. “Once on the field, we couldn’t believe what we were seeing,” Van Wieren wrote. “The radio booth that we had been sitting in 10 minutes earlier was entirely engulfed in flames. So was most of the adjoining press box. The fire apparently had started when a breeze blew part of a paper tablecloth into one of the Sterno burners. Once the flames reached the drop ceiling, which was shared by all of the booths on that level, the fire quickly spread. The boom that Skip and I heard was a steel beam above the drop ceiling exploding from the intense heat.”37

The Braves lost to the Phillies in the NLCS. The 1994 players strike ended that season’s pennant race. “It was agonizing watching millionaires and billionaires bicker over dollars,” Van Wieren wrote.38 Pete had a void during August and September, the time of year when he was used to the edge-of-your-seat pennant race. The time off became a period of personal reflection on his life. By chance, new information had been discovered about his father.

A cousin had called and said some old photographs of Ruth and Howard from the 1940s had been discovered. Donald Dykstra, Howard’s cousin, told Ruth that Howard lived as a derelict on the streets of New York and died in 1971. He was buried in the potters field on Hart Island, off Manhattan, where unclaimed bodies are buried. Howard’s father was notified of his son’s death but refused to claim the body, wanting nothing to do with him. Pete still wanted some sense of closure and decided to visit his father’s grave. The graves were unmarked, and there was no joy in his discovery. “I also learned that the simple coffins are stacked five-deep in numbered sections three rows by ten rows,” he said. “It’s just a dump, is what it is. Knowing what I do about his life, this seems like an appropriate final resting place.”39

The extra time for Van Wieren in 1994 led into his usually busy winter. He had been broadcasting Atlanta Hawks basketball for TBS or the later Turner Network Television (TNT) since 1976, originally handling the radio coverage while Caray handled television. As the popularity of TBS grew in the 1980s, its basketball coverage grew and so did Pete’s exposure in the hard-court world. He worked beside basketball gurus such as Doug Collins, Rick Barry, Steve Jones, and Hubie Brown. Turner also acquired the rights to the Atlanta Falcons preseason football games in 1977. Van Wieren also called college football games for TBS and later University of Florida football on Sportschannel Florida.40

The 1995 season for the Braves began with replacement players in spring training, as the strike continued, but ended with a World Series championship, the first since the franchise moved to Atlanta in 1966. The Braves won the NL East by 21 games. This was their new division following realignment and the addition of a wild-card playoff team. Television coverage had also changed with the new Baseball Network, a joint venture of ABC and NBC. The networks would broadcast every game on the Monday night schedule and include a broadcaster from each team. Van Wieren was chosen as the Braves announcer and his assignments also included the National League Division Series between the Braves and Colorado Rockies, the first NL wild-card team. Pete worked alongside Larry Dierker. “Working that series with Dierker established a friendship and mutual respect,” Van Wieren said. “We truly enjoyed the experience.”41 The Braves won the series, then swept Cincinnati in the NLCS.

The World Series was a matchup between the powerful Cleveland lineup and the Braves’ pinpoint-control pitching. In Game Six, Tom Glavine pitched a masterful eight innings of one-hit shutout baseball, and the Braves won the Series with a 1-0 victory. The longtime Braves broadcasting duo called the game on radio and both were standing in the booth as Skip called the final out. “Yes! Yes! Yes! The Atlanta Braves have given you a championship! Listen to this crowd!”42

The Braves returned to the World Series in 1996, falling to the New York Yankees, while the 1997 club lost in the NLCS to the Florida Marlins. This pattern of regular-season success and failure in the playoffs would become the reputation of the Braves through the rest of the century and beyond. They lost the 1998 NLCS to San Diego, and the World Series to the Yankees in 1999. From 2000 to 2002, the Braves failed to advance beyond the NLCS despite high expectations.

Baseball on television had changed by 2003. Regional sports networks were available throughout the country, meaning TBS was not the only game in town. Ratings had dropped, and TBS executive producer Mike Pearl decided the TV booth needed a shakeup. Skip and Pete were being moved to strictly radio broadcasting. The outcry from the fans was fast and furious, and Skip and Pete were now the focus of media coverage. TBS lost ratings, and the four-man TV-radio rotation returned after the All-Star break. Both veteran broadcasters were humbled by the outpouring of support from the fans.43

The broadcasting duo was back on TBS as the Braves again lost in the NLDS, to the Cubs in 2003 and to the Astros in 2004. In 2004 Skip and Pete were inducted into the Braves Hall of Fame. In his induction speech, Van Wieren made a subtle comment over the actions of TBS management in the previous year. “I would like to thank Ted Turner and Terry McGuirk (the current Braves chairman) for their leadership, their friendship, and their loyalty. I have worked for 11 different executive producers over the years. I would like to thank 10 of them.”44

The Braves won their 14th straight division title in 2005 and again were bumped early in the playoffs. This was the end of an era in many ways, as the 2006 team failed to return to the playoffs. Turner Broadcasting and Time Warner merged, with Time Warner taking control of the team. Ted Turner was gone from the picture. TBS was broadcasting fewer Braves games and agreed to a partnership with MLB to broadcast other games, including the postseason.45 Liberty Media purchased the club in 2007 from Time Warner, and the Braves’ 30-year affiliation with TBS came to an end. Skip and Pete continued to broadcast games on the radio. The Braves missed the postseason again, then fell to 72-90 in 2008.

In August of that year the Braves longtime broadcasting duo came to an end after 33 years. After suffering with health issues related to diabetes, Skip died suddenly. Pete spoke at his funeral. “Every day we’ll hear that voice. Every day we’ll remember that wit, that humor. Every day we’ll recall that attitude. So, instead of saying goodbye, I’m just going to say thank you. Thank you, Skip, for letting us be a part of your life.”46

Van Wieren announced his retirement at the end of the 2008 season, his 43rd year in broadcasting and 33rd with the Braves. “Losing Skip was certainly a tough thing,” Van Wieren noted, “but that didn’t affect my decision. If anything, it reinforced my decision. I didn’t want to keep on working until I couldn’t do it anymore. I really did another whole year of postseason games when you add it up,” he said, referring to the decade-plus of Braves playoff appearances. There were so many great wins, so many great come-from-behind wins, all those great pitching performances. It’s hard to single anything out.”47 Stan Kasten, the Braves’ longtime president, said, “Before there was an internet, Pete was our ‘human internet.’ He collected stats and anecdotes so that he could always be prepared to talk about any player on both teams and really bring the game into the fans’ minds.”48

On April 10, 2009, the Braves honored Pete at the new Turner Field. There were gifts and a video tribute presented, and the radio booth was renamed the Pete Van Wieren Broadcast Booth.49 In 2010 Pete wrote his autobiography, Of Mikes and Men: A Lifetime of Braves Baseball with Jack Wilkinson. Almost exactly a year after retiring, Van Wieren was diagnosed with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and began chemotherapy and radiation treatment. “This is certainly not what I planned to do when I retired,” he said, noting that he planned to travel the world with Elaine and spend time with their grandchildren.50 The experience redefined for him what a true “hero” was. “My heroes used to be the ballplayers,” he told students at the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business in March of 2014. “My heroes now are cancer doctors, oncologists and nurses and the people who work in those facilities, because of the dedication that they show.”51

The Van Wierens celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on June 13, 2014, with a trip to the Bahamas. That was Pete’s last “good day” as his health deteriorated, according to his son Steve in an online memorial. Pete Van Wieren died on August 2, 2014, at the age of 69.

“He lived a tremendous life,” Steve said of his father, “one of which many would dream to live. He lived life to the fullest. But he was more than a broadcaster.”52

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author was assisted by:

Baseball-reference.com

Cassidy Lent, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York, who provided Pete Van Wieren’s file.

Notes

1 Paul Newberry (Associated Press), “Broadcaster Pete Van Wieren Dies,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 3, 2014: D4.

2 Pete Van Wieren and Jack Wilkinson, Of Mikes and Men: A Lifetime of Braves Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010), 11 (Hereafter cited as Biography).

3 Biography, 12-13.

4 Biography, 14.

5 Biography, 15-16.

6 Biography, 17.

7 By then the Red Wings were a farm team of the Baltimore Orioles.

8 Biography, 18.

9 Biography, 90.

10 Bill Dowd, Binghamton Press and Sun Bulletin, January 24, 1969: 15.

11 Dowd.

12 Dowd.

13 Biography, 21-22.

14 The quote is from a speech Van Wieren gave to students at the University of Georgia Terry College of Business, March 2014. youtube.com/watch?v=gvWMGgNk_vQ. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

15 Biography, 23-24.

16 Binghamton Press and Sun Bulletin, October 14, 1967: 23.

17 Biography, 25.

18 Dowd.

19 Biography, 25-27.

20 Biography, 27-29.

21 Biography, 29-32.

22 Jack Wilkinson, “Skip & Pete, Whatta Team, Whatta Show,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 11, 2004 (online).

23 Larry Bump, “Van Wieren Moving Up,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 3, 1975: 69.

24 Biography, 150-151; Mark Armour, “Jim Brosnan,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/b15e9d74. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

25 Biography, 204.

26 “Donald Davidson,” New York Times, March 30, 1990: D17; Richard Luna (United Press Internaional), “Baseball’s Biggest Man, Donald Davidson, Is Fighting for his Life,” October 8, 1986. upi.com/5423425. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

27 Biography, 33.

28 Sam Hopkins, “TV-17 Cable Net Opens Friday,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, December 17, 1976: 92; Richard Zoglin, “WTCG to Become WTBS on Aug. 27,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, August 8, 1979: 29.

29 Biography, 39.

30 Biography.

31 Biography, 39-44.

32 Biography, 47.

33 Transcript taken from a YouTube video of the game originally played July 6, 1986. youtube.com/watch?v=aODckrL9fVk. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

34 Biography, 49.

35 Biography, 73.

36 Biography, 76.

37 Biography, 85.

38 Biography, 89.

39 Biography, 92.

40 Biography, 119-128.

41 Biography, 101.

42 Biography, 105.

43 Biography, 161-166.

44 Biography, 169.

45 Biography, 171-172.

46 Biography, 188.

47 “Braves Radio-TV Announcer Van Wieren Retires After 33 Seasons,” SI.com, October 22, 2008.

48 Associated Press, “Longtime Braves Broadcaster Van Wieren Dies at 69,” August 2, 2014.

49 “Braves Radio-TV Announcer.”

50 Mark Bowman, MLB.com, “For Pete’s Sake.” Undated article in Van Wieren’s Hall of Fame file.

51 youtube.com/watch?v=gvWMGgNk_vQ.

52 “Peter Dirk Van Wieren,” Dignity Memorial. dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/roswell-ga/peter-vanwieren-6070806. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

Full Name

Van Wieren

Born

October 7, 1944 at Rochester, NY (US)

Died

August 2, 2014 at Atlanta, GA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.