Phil Ball

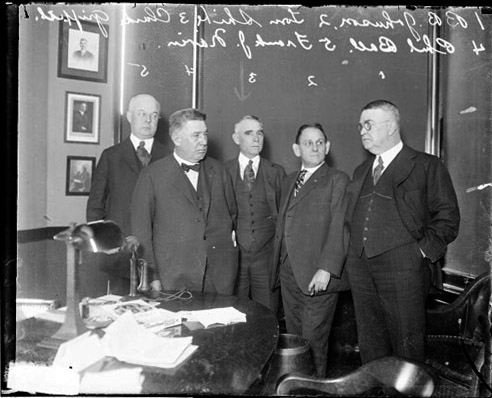

St. Louis Browns owner Phil Ball, second from left, meets with American League owners Frank Navin (Detroit Tigers, far left), Clark Griffith (Washington Senators, middle), Ben Shibe (Philadelphia A’s, second from right), and American League president Ban Johnson, far right, in Chicago, circa 1920. (Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News collection, SDN-062283)

Phil Ball was the owner of the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League (1914-1915) and bought the American League’s St. Louis Browns in December 1915, as part of the settlement between Organized Baseball and the upstart league.1 In 1917 he said, “I’ll pay — well, I’ll go to the limit — to get a world’s series for St. Louis. … I’m just as interested in a ball game as the kids who hand their two bits over the windows for the bleacher seats.”2 He owned the Browns until his death in October 1933 but never won an AL pennant, though he came close in 1922. He was a fiery and gruff man, who, in the words of a St. Louis magazine writer, did “not affect a great softness of manner, unruffled evenness of temper or a slow and deliberate enunciation.”3 He was also the only club owner who challenged the authority of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and did so more than once.

Philip De Catesby Ball was born in Keokuk, Iowa, on October 22, 1864, to Charles Ball, a West Point graduate who fought in the Civil War, and Caroline (Paulison) Ball. His mother wanted to name him after a great-uncle and famous commodore in the US Navy, Thomas ap Catesby Jones.4 She did not care for “ap” and instead inserted “De” in her son’s name. Charles was an engineer who started an ice business in 1878, with refrigeration equipment that produced ice.5 The Ice and Cold Machine Company built ice plants in the South and Midwest, and Phil Ball did various jobs for his father’s company, from collecting bad debts to driving an ice wagon to overseeing the construction of ice plants. The family lived in Sherman, Texas, for a number of years when Phil was a teenager. Before joining his father’s company, Phil worked at many jobs, including surveying, railroad work, and hunting buffalo.6 For this reason, Arthur Mann wrote, “Ball was a gruff and growling Iowan of 56 [b.1864] who had been everywhere and done everything.”7

Historian Daniel Boorstin has written about the central role ice has played in “democratizing the national diet” and “homogenizing the regions and seasons.”8 Until refrigerators became common household appliances in the 1920s and 1930s, the icebox was the kitchen cold-storage unit, with blocks of ice supplied by ice plants. When Charles Ball retired to California (where he died in 1901), Phil bought his company for $20,000 and built it up.9 In a 1932 article in The Sporting News, Harry Brundidge reported that Ball had 156 ice plants, including the world’s largest, at Anheuser-Busch. “It has been said that I inherited my money from my father, but I never got a nickel from anybody,” Ball said.10 Although he was a civil and mechanical engineer, Ball had no technical-school training.

When Ball lived in New Orleans, he played amateur-league baseball, but his career ended when he was stabbed in a barroom brawl. Sportswriter Dan Daniel wrote, “Philip De Catesby Ball is a born scrapper. You have only to look at his determined jaw to discern that.”11

He married Harriett Heiskell of Indiana in 1885. They had three children and then moved to St. Louis in the 1890s. His son, James, was a supervising engineer for the Ice and Cold Machine Company. His younger daughter, Phillipa (Mrs. John Nulsen), died in 1918. His older daughter, Margaret, married an accomplished ice skater, William Cady, one of the founders of the St. Louis Skating Club. In 1916 a St. Louis building from the 1904 World’s Fair was converted to the St. Louis Winter Garden ice-skating rink, with the support of the Ball Ice Machine Company.12

The Federal League began as a Midwestern minor league in 1913, and a group of 14 St. Louis men, including Phil Ball and brewer Otto Stifel, each put up $1,000 for the city’s club. When the league decided to go national and challenge Organized Baseball in 1914, only Stifel and Ball remained as owners from what was known as the “Thousand Dollar Club.” Ball’s fellow oil executive Harry F. Sinclair (Ball had substantial oil investments), founder of Sinclair Oil, joined them as owner of the Browns. Sinclair soon moved on to become one of the major backers of the league as a whole.13

When the Federal League was taking on Organized Baseball in early 1914, Ball urged his fellow owners to invest the necessary capital. “We’ve got the opportunity of a lifetime, but some of you fellows seemed to think too much of your bankroll. Some of you fellows seem to be showing the ‘white feather’ [a sign of cowardice].”14 He told reporters later that year, “They [Organized Baseball] are going to get a financial and legal raking that they never dreamed of. … We are willing to match money and brains against anything organized ball may have to offer.”15 Ball had diversified interests beyond ice. He owned a 10,000-acre ranch and had investments in oil.

During the 1914 season the Terriers signed Cuban star Armando Marsans from the Cincinnati Reds. What Baseball Magazine called “the sensational Marsans case” played out in the courts.16 The Reds secured an injunction that kept Marsans on the sidelines for more than a year. Ball tried unsuccessfully to get the injunction lifted in Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s court. Historian Robert Wiggins wrote that as part of the Federal League settlement, Reds owner Garry Herrmann paid Ball $2,500 in damages for keeping Marsans from playing for the Browns.17

Ball was pursuing one of baseball’s biggest stars, pitcher Walter Johnson, for his Terriers after the 1914 season. When Johnson did not sign with the Terriers, Ball let the Federal League’s Chicago Whales sign him. In return Ball got the right to pursue pitcher Eddie Plank, whom he signed for 1915.18 When Johnson reneged on his contract with the Whales, Ball told the press, “If Johnson pitches for any team besides the Chicago Feds next season, it will be in Leavenworth, Kansas, and his identity will be hidden behind a number.”19

In 1914 Chicago pitching great Mordecai Brown was the Terriers’ manager.20 With the team mired in seventh place in August, Ball replaced Brown with more of a disciplinarian, Fielder Jones. The manager of the 1906 world champion Chicago White Sox Hitless Wonders, Jones was lured out of retirement with an interest in the club’s ownership and a hefty three-year guaranteed contract of $50,000.21 While Jones could not turn around the Terriers at the end of the season, he achieved success the following year. The 1915 Terriers (87-67, .565) fell just short of the Chicago Whales (86-66, .566). It was the closest pennant race in major-league baseball history.22

Under the settlement, two Federal League team owners, Charles Weeghman of Chicago and Phil Ball, were allowed to buy existing teams of the major leagues, the Cubs and the Cardinals, respectively. Ball was anxious to acquire an established team, even though he revealed he had lost $182,000 in his two seasons with the Terriers.23 But when Helene Britton, the owner of the Cardinals, decided not to sell (she resented the male owners trying to force out the game’s only female owner), the entire settlement with the Federal League was threatened.24

At this point, Robert Hedges decided to sell his American League club, the St. Louis Browns, to Ball.25 Hedges had facilitated the 1903 peace treaty between the American and National Leagues by returning Christy Mathewson to the New York Giants.26 “Maybe once again St. Louis will have to be the central figure in establishing peace in baseball,” he said.27 Hedges sold the Browns and Sportsman’s Park for what was variously reported as between $425,000 and $550,000.

The 1916 Browns (like the Cubs) had the benefit of drawing on players from two teams, the Terriers and the Browns. Ball made Jones the manager of the combined team and moved Branch Rickey, the Browns’ manager, into the front office. He could not fire Rickey because Hedges had given him a contract for 1916.28 The two men did not get along from the start. “So you’re the goddamned prohibitionist!” Ball reportedly said to Rickey when they first met.29 “Ball thought Rickey’s ideas too radical, and Rickey’s endless talk and large vocabulary made him uncomfortable,” wrote Murray Polner in his Rickey biography. “Rickey was, in turn, uncomfortable with Ball’s crudeness: he considered Ball uncouth and, in matters of baseball, virtually illiterate.”30

The 1916 Browns finished a disappointing fifth in the AL with a 79-75 record. But 1917 was much worse, with 97 losses against only 57 wins. Rickey was gone before the start of that season; he became the president of the St. Louis Cardinals early that year, after a citizens group bought the club from Helen Britton for $375,000.31 At first Ball supported Rickey’s move. But after consulting with American League President Ban Johnson, who did not want to lose the talented Rickey to the National League, Ball changed his mind. “Just tell those bastards you can’t go through with it,” he told Rickey, who replied, “Mr. Ball, whether or not I ever go with the Cardinals, I’ll never work another day for you.”32 The dispute headed to the courts and had an odd settlement: Rickey was enjoined from joining the Cardinals, but only for 24 hours.

In early September 1917, Ball was again in the center of a controversy — one that he created. He was so upset with a 13-6 loss to the White Sox on September 4 that he decreed he’d cut salaries $100 for every $1,000 he would lose. “If these ball players think they are getting away with something on me by ‘laying down,’ they are all wrong, all wrong.”33 Three of the club’s players, infielders Del Pratt and Doc Lavan, and outfielder Burt Shotton, took issue with Ball and refused to suit up. Ball had not mentioned names, but these three men were having poor seasons, in no small part because of injuries.

Pratt and Lavan sued Ball for libel for $50,000 each. Ball then backtracked and said, “I have been told they [some of his men] were laying down, but that I myself am not competent to judge of that.” The writer of the St. Louis magazine Reedy’s Mirror noted that Ball “has not the polished mien one finds in some successful business men, nor the insouciance noted in others. … He is not a man whose actions bespeak craft or design. He is just a plain whole-hearted individual, with the pugnacious tenacity of a leader.”34

Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton said that Ball should be eliminated from Organized Baseball. “The fans ought to get up a memorial to Johnny Lavan and Derrill Pratt for bringing suits against Ball,” he wrote. “For a man of the Ball type to accuse men of the moral and mental standing of Lavan and Pratt is a final blow to baseball in St. Louis.”35 Both men, along with Shotton, were traded before the 1918 season. Eventually Pratt and Lavan dropped their lawsuits after receiving $2,700 each.36

Fielder Jones was a stern taskmaster, and his abrasive style created dissension on the Browns. Yet in early 1918, Ball told the press that Jones had been too lenient. “No more Coddling — Iron Fist to Rule Browns Hereafter” was his message.37 Just a few months later, after a painful loss by his Browns, Jones suddenly resigned and walked away from baseball forever.38 When Ball got the news, he erupted. “So you want to quit? You haven’t an ounce of courage. Get out of my office. I wouldn’t take you back if you’d work for nothing.”39

Early in his ownership of the Browns, Ball made perhaps his best and worst baseball decisions. In 1917 he hired Bob Quinn, a decent man and sharp evaluator of baseball talent, to replace Branch Rickey as business manager. “There’s really nothing to the job. All you need is bunk and bluff,” Ball told him. Quinn replied, “I have never practiced bunk or bluff in my life.”40 What Quinn practiced was solid, uncanny team-building. Through trade and acquisition, he assembled a powerful club that came within one game of the 1922 AL pennant.

Fred Lieb said that Quinn once canceled a Browns home game because of damp weather; he thought Ball would make more money if the game was rescheduled. But Ball was furious. “Bob Quinn, let me tell you something. I worked myself to a frazzle at the office so I could see this game, and if you want to keep your job, don’t ever do anything like this to me again.”41 Yet Quinn was no “yes man” and insisted that Ball not interfere with baseball operations. He once even walked out for a few days when Ball pushed his meddling too far.

Ball made arguably his worst baseball decision in 1920. The St. Louis Cardinals were in a desperate financial state, and their ballpark, League Park, was decrepit. Their president, Sam Breadon, who was consolidating ownership of the club, repeatedly begged Ball to allow the Cardinals to play their home games at the Browns’ Sportsman’s Park. In 1918, when Ball turned him down, he suggested that Breadon sell to Kansas City sportsmen.42 Ball finally relented, even though he detested Branch Rickey, who by this point was the Cardinals manager. He felt sorry for Breadon and admired his fighting nature.

The Cardinals played their first home game in Sportsman’s Park on July 1, 1920. They sold their League Park property for $275,000: $200,000 to the school board (Beaumont High School operated on the land until 2014) and $75,000 to the transit company for a streetcar turnaround. “The deal gave us money to clean up our debts, and something to work with,” said Breadon. “Without it, we never could have made our early purchases of minor-league clubs.”43 Would the Cardinals have left St. Louis? It’s hard to say. Instead, now Rickey’s farm system would become a reality. The club had the money to start buying minor-league teams.

Ball became close friends with American League President Ban Johnson, even though they were “warring parties during 1914-1915.44 Fred Lieb noted, “Despite Ball’s truculence and quirks, he was intensely loyal.”45 When Ban lost power with the demise of the National Commission in 1920 and the rise of the commissioner system, Ball became a fierce opponent of Commissioner Landis. At one heated owners meeting in early 1920, Ball and Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert almost came to blows. When the owners voted to hire Landis later that year, Ball was the only one not to vote for the new commissioner (though he let Bob Quinn vote for the judge).

In the fall of 1924 Landis and Johnson came into open conflict, when Johnson recommended the cancellation of the World Series in the wake of the O’Connell-Dolan affair, a scandal involving attempts to throw ballgames. Landis demanded that Johnson be reprimanded; the owners responded with a resolution that humiliated Johnson. They felt they had to support Landis — or risk destroying fan confidence in the game’s integrity. Eugene Murdock, Johnson’s biographer, wrote, “It is unlikely that any group of subordinates had ever humiliated their superior officer so completely.” Ball refused to sign the document and said, “The biggest figure in the national game has been a victim of men whose gratitude has bowed to the dollar sign.”46

Late in his life, Johnson expressed what Ball meant to him. “I owe my life to Phil Ball. He stepped in and took charge of my case and refused to permit amputation of my leg.”47 NEA Service sportswriter William Braucher summed up their relationship: “Ball stood shoulder to shoulder with Johnson in every important battle the great old fighter had. Even the last battle that Johnson finally lost — for his life.”48

The dramatic 1922 AL pennant race generated a large profit of around $300,000 for Ball.49 He paid out bonuses of around $20,000 that year.50 A decade later, Ball said, “The Browns made money for me in 1922, not before, not since. As president I get no salary, and I run the club for the pure fun of it.”51 Sportswriter Dan Daniel said that Ball set aside $250,000 each winter to run the Browns in the coming season. “I’d give anything to win with the Browns,” said Ball. “Well, money is no object. Baseball is not only a hobby with me, it is a source of relaxation.”52

In 1923 Bob Quinn left the Browns to take over the presidency of the Boston Red Sox, after Harry Frazee sold the team. Quinn had also tired of pushing back against Ball’s interference. Ball felt the quiet manager of the Browns, Lee Fohl, was an ineffectual leader who had done a poor job of rallying his team after they lost two out of three games in a crucial September series against the New York Yankees.53 With Quinn gone, Fohl now had to deal directly with his team’s owner.

On July 27, 1922, controversial Browns pitcher Dave Danforth had been suspended by the league for throwing a ball whose seams were loaded with dirt or mud.54 Quinn and Fohl sent Danforth down to the club’s Tulsa farm club for the rest of the season. They did not want to bring him back in 1923, but Ball overruled them. On August 1, 1923, Danforth was again suspended, this time for throwing a doctored ball that had rough spots. When his teammates signed a petition to Ban Johnson, Fohl refused to do so. St. Louis Times sports editor Sid Keener wrote, “I know the character of Lee Fohl. … If Lee wouldn’t sign [the petition], there must be some black smoke in the air.”55

But Ball fired his manager a few days later and told reporters, “For the good of the game and the morale of the club, Lee Fohl is hereby relieved of his duties as manager.”56 When Fohl felt his integrity had been demeaned, Ban Johnson persuaded Ball to reword his statement: “For the good of the game as played by the Browns’ team …”

Just a month later, as the Browns left for their final East Coast swing, they suspended star pitcher Urban Shocker. He had already won his 20th game of the year on August 30, his fourth consecutive 20-win season. The temperamental spitball pitcher insisted on taking his wife along on the trip, but the club’s new business manager, Billy Friel, denied the request. Since Bob Quinn’s departure, Phil Ball was really making all the major decisions; Friel’s executive experience and reputation did not come close to that of the man he replaced.57 Syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler wrote that Ball’s philosophy was, “Women in baseball are like gun play in a crowded street car.”58

Ball and Friel, with Ban Johnson’s full support, contended that this was the simple issue of an insubordinate employee not following team rules, as he had agreed to do in his contract. To Shocker, however, this was a violation of his personal liberty, and he took his case to Commissioner Landis, who was the ultimate arbiter. Landis was also an unpredictable “wild card” in the dispute. Even as a judge, he enjoyed defending the rights of the little guy in struggles with management. And Landis certainly did not want to uphold a position held by his nemesis, Ban Johnson.

Sportswriter Fred Lieb wrote, “There is a stick of dynamite in the Shocker case. It is fraught with danger.”59 Ball did not like to compromise when he felt he was right, and even more so in dealing with Shocker, whom he disliked. But should Landis declare Shocker a free agent, Johnson and the owners feared the reserve clause would come into challenge, opening the door to “a legal fight that might shake baseball to its foundation.”60

Johnson decided the risk of a Landis ruling was too great, fireworks that would have made “the Last Days of Pompeii look like a wet match” by comparison.61 He facilitated a settlement: He pulled Bob Quinn into a meeting with Shocker, in which Ball had allowed his friend Johnson to act on his behalf. Shocker signed a 1924 contract with a large salary increase, more than enough to cover the fine Ball had levied.62 He then withdrew his hearing with Commissioner Landis. Ball wanted to trade Shocker, but he had recently hired the club’s star first baseman, George Sisler, as player-manager, and Sisler wanted to keep the talented pitcher. A year later the Browns did trade Shocker, to the Yankees, after Sisler decided it was time for the unhappy pitcher to leave St. Louis.

The Browns did not come close to the pennant in the next few years. In early 1925 Phil Ball felt the brunt of St. Louis fans’ ire, when outfielder Baby Doll Jacobson was locked in a salary dispute. After fans booed the club’s owner in an early-season game, Ball called them “the sort of persons who throw pop bottles at umpires.”63

After the 1925 season Ball spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to remodel and expand Sportsman’s Park.64 After the Browns finished in third place in 1925, he felt they would compete for the 1926 pennant. How wrong he was: The 1926 Browns fell to a 62-92 record and seventh place. And his tenants, the National League’s Cardinals, won the World Series.65 Ball did not renew Sisler’s contract as manager and said, “The complete failure of the team this year is all the explanation that is necessary to make, I think.”66 He added a dig at the mild-mannered Sisler when he added, “The next manager of the team will be a rigid disciplinarian and a man able to command the enthusiasm of the players and their best efforts.”67

Under new manager Dan Howley, a successful minor-league skipper, the Browns again finished seventh. Westbrook Pegler wrote about Howley’s “peculiar job.” “Starting with nothing, it is his duty to prevent it from becoming less.”68 Ball, acting as his own business manager, decided to rebuild his team. “Our club is loaded up with players who have had long trials and have failed to come through. We also have several malcontents who do the club no good. All the dead and dying timber will be culled.”69

Ball was a brusque and impatient man; he always seemed to be in a hurry. Perhaps his restlessness led to his love of flying his own planes. It was not unusual for him to fly to meetings in Chicago and Detroit and return home the same day. He flew a Ryan monoplane, the same model as the one Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic. Ball even bought the plant that built them.70 In 1928 he told a reporter that he saw a future in which baseball teams would travel by airplane.71

In 1929 Howley tired of his owner’s interference and told reporters Ball came into the clubhouse and humiliated him in front of the players. “It makes no difference where the club finishes. If we win the pennant, I’m through just the same. I’m quitting.”72 Ball replaced Howley with Browns coach (and former catcher) Bill Killefer.

In 1930 Ball had a legal showdown with Commissioner Landis. Fred Bennett was an outfielder Ball had shuttled between his minor-league farm teams for more than two years. Landis ruled that since the Browns did not bring Bennett to the major leagues, he was a free agent.73 Ball got a temporary injunction that allowed him to keep Bennett in the minors in 1930. A judge upheld Landis, giving Bennett his freedom.74 Ball planned to appeal, but he dropped it, he said, “at the request of the American League.” Landis had been fighting a rear-guard action against the farm system, which was called “chain-store baseball.” Early in 1933 the owners voted 16-0 to allow clubs to own farm teams. Ball introduced the measure.75

In July of 1933 Ball fired Killefer and replaced him with Rogers Hornsby. Ball earlier had told reporters, “I wish I had a fellow like Hornsby running this team. He’d make those fellows click their heels.”76 This would be Ball’s last major official act as the owner of the Browns. A couple months later he took ill while vacationing at his cabin in Battle Lake, Minnesota, and died of septicemia on his 69th birthday, October 22, 1933.

Phil Ball was not amused by the saying about St. Louis, “First in shoes, first in booze, last in the American League.”77 Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter Ed Hughes wrote, “Ball was willing to lose fortunes in order to feel the glow of satisfaction in owning a champion club. … He had disclosed his intention to quit the game once his Browns had ‘come through.’ When they failed, he kept on spending and spending and fuming at his inability to produce the winning combination.” After the 1936 season, in which the Browns drew an average of only 1,260 fans a game, his executors sold the club to Don Barnes of the American Investment Company of St. Louis for $350,000.78

This biography originally appeared in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tom Bourke for providing genealogical and ice history information.

Notes

1 In 1913 the Federal League operated as a minor league based in the Midwest, a year before it challenged Organized Baseball and began raiding major-league teams of players. St. Louis brewer Otto Stifel and E.E. Steininger were Ball’s partners in the Terriers. At first, Stifel was the largest shareholder.

2 Sid Keener, St. Louis Times, September 10, 1917.

3 Reedy’s Mirror, December 18, 1914.

4 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News, October 26, 1933.

5 Ice and Refrigeration, Chicago, September 1901, Vol XXI, No. 3. It was a modified Carré machine that cost $12,000 and made five tons of ice a day. Frenchmen Ferdinand and Edmond Carré invented ice-making machinery in the 1850s.

6 “Famous Magnates of the Federal League,” Baseball Magazine, October 1915: 71-72.

7 Arthur Mann, Branch Rickey, American in Action (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1957), 84.

8 Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Democratic Experience (New York: Vintage, 1974), 327.

9 One source said that Phil paid the $20,000 for the patents. Bill Borst, Baseball Through a Knothole (St. Louis: Krank Press, 1980), 3.

10 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News, October 26, 1933. Ball said his father left what little money he had to a brother, a sister, and a third wife.

11 Dan Daniel, The Sporting News, February 11, 1932.

12 Susan Brownell, “Figure Skating in St. Louis — After 90 Years, ‘Meet Me in St. Louis,’” St. Louis Skating Club, stlouisskatingclub.org/index.php/history-by-susan-brownell. Also, email from Susan Brownell to Tom Bourke, September 9, 2016. The rink was demolished in 1964.

13 “Famous Magnates of the Federal League,” 66-74.

14 Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Baseball Clubs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 53.

15 Washington Post, December 4, 1914.

16 Eric Enders, “Armando Marsans,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproject.

17 Wiggins, The Federal League of Baseball Clubs, 244.

18 Washington Post, December 4, 1914. The 39-year-old Plank posted a 21-11 record and a 2.08 earned-run average for the Terriers in 1915.

19 Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington: Phenom Press, 1995), 137-138.

20 Brown had a 12-6 record with the Terriers.

21 Grantland Rice reported this salary figure in Collier’s magazine. David Larson, “Fielder Jones,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproject.

22 The closeness of the race was the result of the teams not playing the same number of games. Ironically, Mordecai Brown was a 17-game winner for the Whales.

23 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 18, 1916.

24 The Sporting News of January 6, 1916, had a photo of Britton with the headline, “Never Tell Her She Must.”

25 Steve Steinberg, “Robert Hedges,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproject.

26 Hedges had signed Mathewson to an ironclad contract in the summer of 1902.

27 Sid Keener, St. Louis Times, November 14, 1914.

28 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 130.

29 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon, 2000), 75.

30 Murray Polner, Branch Rickey: A Biography (New York: Atheneum, 1982), 74.

31 Frederick G. Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1944), 60.

32 Golenbock, 76-77.

33 St. Louis Republic, September 5, 1917. “Laying down” suggested throwing games by not playing well.

34 Reedy’s Mirror, December 18, 1914.

35 Hugh Fullerton, New York American, September 17, 1917.

36 Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), May 8, 1918. Ball claimed he did not pay for any settlement. It is possible the American League paid the players to drop their suits. In 1919 Rickey brought Lavan and Shotton back to St. Louis, to the Cardinals.

37 This was the headline in The Sporting News, February 7, 1918.

38 Jones told Baseball Magazine (October 1915): 73, “I left the game [as player-manager of the White Sox in 1908] because I was tired of it. It is a great strain to manage a club day after day.” He had a heart condition that was not known at the time. He died of heart disease at the age of 62.

39 Frederick G. Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles (Carbondale, Illinois: SIU, 2001), 191 (reprint of 1955 Putnam edition).

40 Rory Costello, “Bob Quinn,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproject.

41 Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles, 190.

42 Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1918. The Cardinals paid the Browns an annual rent of $20,000.

43 Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals, 78.

44 The two men had meetings during negotiations, and Ball was Johnson’s guest at Opening Day 1915 at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Eugene Murdock, Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 1982), 115.

45 Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles, 191.

46 Murdock, Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball, 211.

47 Huron (South Dakota) Evening Huronite, December 26, 1930.

48 Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror, April 28, 1931.

49 “Phil Ball,” UPI obituary, October 22 dateline, in Baseball Hall of Fame Library Phil Ball file.

50 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News, October 26, 1933.

51 Harry T. Brundige, The Sporting News, October 20, 1932.

52 Dan Daniel, The Sporting News, February 11, 1932.

53 The Yankees came into St. Louis on September 16 with a one-half game lead. They took two of three games before enormous crowds and left town with a 1½-game lead. The Browns then split six games against second-division clubs and ultimately fell one game short of the pennant.

54 Steve Steinberg, “Dave Danforth: Baseball’s Forrest Gump,” The National Pastime (Cleveland: SABR, 2002).

55 Sid Keener, St. Louis Times, August 3, 1922.

56 St. Louis Times, August 6, 1923.

57 Quinn had been the business manager of the Columbus Senators of the American Association for many years.

58 Westbrook Pegler, United News, February 7, 1924.

59 Fred Lieb, New York Evening Telegram, December 11, 1923.

60 The Sporting News, quoted in Steve Steinberg, “Urban Shocker: Free Agency in 1923,” The National Pastime (Cleveland: SABR, 2000).

61 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 26, 1923.

62 Johnson did not want to rescind the fine because he knew that Ball’s pride was involved. Quinn had maintained a good working relationship with Shocker.

63 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 19, 1925. Jacobson soon signed his 1925 contract.

64 Curt Smith, in Storied Stadiums (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001), pegged the remodel cost at $500,000. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said the figure was $600,000 (October 21, 1927).

65 The Browns drew only 283,986 fans and lost $75,000 in 1926; the Cardinals drew 660,428.

66 Washington Post, October 12, 1926.

67 Rick Huhn, George Sisler, Baseball’s Forgotten Great (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 210.

68 Westbrook Pegler, Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1928.

69 Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1927.

70 Washington Post, June 23, 1927; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 17, 1927; Fairfield (Texas) Recorder, June 18, 2015.

71 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 30, 1928.

72 Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror, July 26, 1929.

73 David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend: Diamond Communication, 1998), 349-352. In the complicated case, Bennett petitioned Landis for free agency since Ball wanted to keep him in the minors for a third year. The rules of Organized Baseball limited owners’ control to only two seasons.

74 Bennett hit .368 with 27 home runs for Wichita Falls of the Texas League in 1929. But he played in only 39 major-league games.

75 G. Edward White, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1955 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), 291.

76 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News, October 26, 1933.

77 New York Herald Tribune, October 23, 1933.

78 Branch Rickey played a key role in bringing Barnes and the Ball estate together, for which he was paid $25,000. Sportsman’s Park was not part of the deal; Barnes negotiated the rent down from $35,000.

Full Name

Philip De Catesby Ball

Born

October 22, 1864 at Keokuk, IA (US)

Died

October 22, 1933 at Battle Lake, MN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.