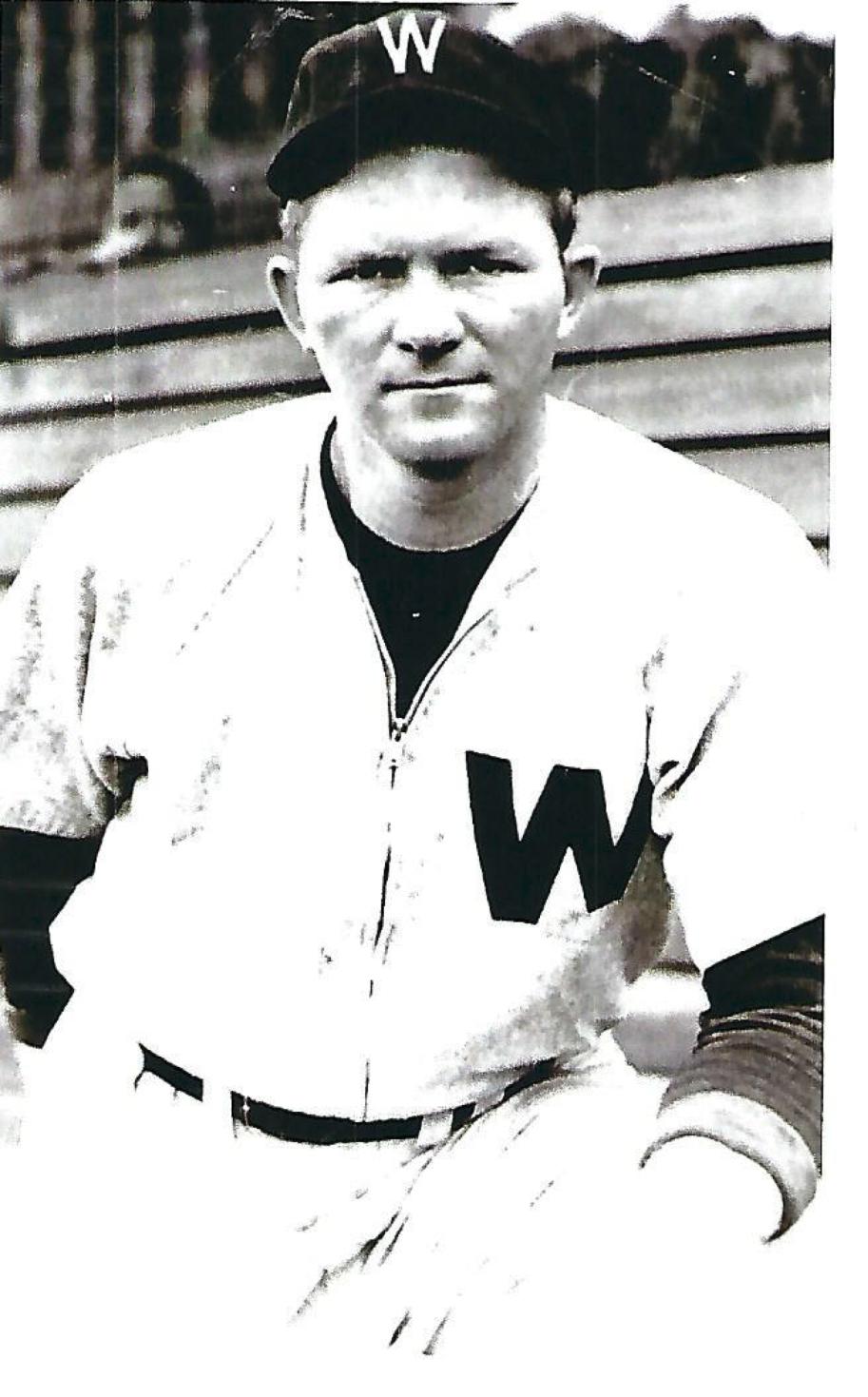

Phil McCullough

Phil McCullough remembered sitting in sleet and freezing rain in the Washington Senators’ bullpen in Griffith Stadium on April 22, 1942. “It was just a terrible day. We tore up chairs and benches and furniture to make a fire in the bullpen to keep warm. It was so cold.”1

Phil McCullough remembered sitting in sleet and freezing rain in the Washington Senators’ bullpen in Griffith Stadium on April 22, 1942. “It was just a terrible day. We tore up chairs and benches and furniture to make a fire in the bullpen to keep warm. It was so cold.”1

The sturdy (six-foot-four, 204 pounds), curly-haired right-hander was a 24-year-old rookie who had been impressive enough in spring training to make the trip north with Bucky Harris’s team. As a college ballplayer with only three minor league seasons—two of them in lowly Class D—on his professional resume, he had relished the chance to show what he could do coming off a decent year in the Class B South Atlantic League and his spring success. In the midst of the World War II housing shortage in Washington, he had located a place to live and had brought his wife, Mary Ruth, to town, anticipating meeting the challenges of baseball’s big time.

McCullough got an opportunity to make his pitching debut that day against the visiting Boston Red Sox. He recalled thinking “Yes, I was a rookie, but I had good stuff” after he closed out Boston in order in the seventh inning.2 But after difficulty in his two other innings and sitting idle for a few days, he was assigned to Chattanooga (Southern Association); Harris had abruptly decided his struggling starting pitchers needed different relief help. And, as the vicissitudes of life and service in the wartime South Pacific intervened, those three relief innings on a cold April day in Washington became the sum total of McCullough’s major-league career.

As an indirect consequence, though, the city of Atlanta public schools gained an innovative career educator they otherwise might not have had.

Pinson Lamar “Phil” McCullough was born July 22, 1917, in Stockbridge, Henry County, Georgia, a railroad town 25 miles southeast of Atlanta. He was named Pinson in honor of the doctor who delivered him. But growing up, he was generally known as “Lamar.” In college, his “P. L.” initials resulted in his being called “Phil,” the name he was generally known by, other than to his parents and those who knew him as he grew up in Stockbridge, the rest of his life.3, 4 He was the middle of three sons of John Dalton McCullough Sr. and Jessie E. (Rountree) McCullough, both native Georgians of Scots-Irish and English descent. John McCullough Sr. was the proprietor of a general merchandise store in Stockbridge. Brothers John Dalton Jr. and Chester (“Chet”) were born in 1908 and 1922, respectively.

Given his size and athletic ability, Phil naturally gravitated to the usual team sports triumvirate of baseball, football, and basketball at Stockbridge High School. “I was much better at baseball,” he told baseball historian Richard Tellis.5 The team had a small roster, and although Phil considered himself a pitcher, he also played outfield and first base. In lieu of American Legion baseball, which Stockbridge lacked, McCullough played for amateur teams sponsored by local businesses.

In the fall of 1934 after high school graduation, McCullough enrolled at Oglethorpe University6 in suburban Atlanta as a physical education and recreation major. He played freshman baseball in 1935, then three seasons for the Stormy Petrels’ varsity.7 When teammate Harry Dean no-hit the Mercer Bears on May 18, 1936, McCullough led Oglethorpe’s 11-run, 13-hit attack.8 He was part of coach Frank Anderson’s pitching rotation in 1937, trusted with an early-season start against the University of Florida.9 At the end of his senior season in 1938 he was one of five members of the baseball team, “all first-stringers,” honored for academic excellence—a scholastic average of 90 or above for the fall and winter terms—at Oglethorpe.10 His steady performance as both a mainstay of the baseball team and as an honored student-athlete resulted in McCullough’s selection to the Oglethorpe University Athletic Hall of Fame with the class of 1995.11

McCullough played mill-league baseball in Alabama during the summers following his college seasons. “We painted houses three days a week and got paid for that, then played ball three days a week,” he remembered in his profile by Richard Tellis.12 He wasn’t “scouted” as such, but the progression of his college and summer mill-league experience caught the eye of Doc Smith, a former member of the Southern Association’s Atlanta Crackers, who was at the time player-manager of the unaffiliated New Bern (North Carolina) Bears in the Class D Coastal Plain League. Smith signed the 21-year-old to pitch for New Bern in 1939—McCullough remembered in his Tellis profile “I think I got $147 a month”—and he logged 195 innings as Smith’s number four starting pitcher.13

McCullough was not only a recent college graduate embarking on a professional baseball career; he was also a newlywed. He and the former Mary Ruth Oliver of Alpharetta, Georgia, an Atlanta suburb, had met on a blind date during McCullough’s senior year at Oglethorpe; they were married on March 12, 1939, after eloping. Mary Ruth traveled with Phil throughout his baseball career, then lived with her extended family in Atlanta’s Little Five Points neighborhood and did clerical work for the Department of the Navy during his military service.

McCullough never got back to New Bern except as a visiting player. “Washington bought my contract after that [1939] season. I found out about it when I was planning to go back to New Bern the next year and they told me to go to Kinston instead.”14 The Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles were another club in the Coastal Plain League, but because Kinston had a working agreement with the Washington Senators, McCullough was now, albeit at the lower rungs, with a major league organization. Kinston and New Bern, only 35 miles apart along the Neuse River in the eastern end of the Tarheel State, had been “bitter athletic rivals for more than 30 years. The feud, on one occasion years ago, resulted in a riot.”15 Brand new to Kinston, McCullough participated as the players marched to center field before the opening game of the 1940 season in Kinston and ceremonially buried a hatchet.

McCullough pitched for two managers at Kinston, as William Averette, who occasionally appeared on the mound in addition to managing, replaced Denny Sothern on July 4.16 Part of the starting rotation, McCullough pitched 148 innings over 29 games, winning seven and losing 12. One of the losses was against the Greenville (North Carolina) Greenies on the road; the game was scoreless through nine innings, but McCullough and Kinston lost his six-hitter, 1-0, on a single, sacrifice, and a single in the 10th.17 Kinston did well enough to advance to the finals of the Coastal Plain League Shaughnessy playoffs, where the Eagles lost, 4 games to 2, to the Tarboro Cubs.18

With fellow starting pitcher Bill Zinser, McCullough got the call to jump two minor-league levels in the Senators’ organization for 1941—to the Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners of the Class-B South Atlantic (“Sally”) League. There, he caught up with college teammate Harry Dean, also a Washington farmhand. McCullough, Dean, Zinser, all righties, and Agapito Mayor, a 25-year-old Cuban lefty, were the core of manager Gus Brittain’s pitching staff, as Greenville finished seventh in the eight-team circuit.19

Three games spread over the season were illustrative of McCullough’s yo-yo season with a Spinners team that finished 17 games under .500. In May, his curve ball, “as wrinkly as a prune, kept the [Columbia] Reds off stride for easy outs” early in the game, but Greenville lost, 7-6.20 Then, a few days later, McCullough held the Columbus (GA) Red Birds to three runs and hit a two-run homer in the ninth inning of his complete game as Greenville won, 6-3.21 On August 19, McCullough “hooked up in a brilliant mound duel” with Frank Marino of the Macon Peaches, but lost a heartbreaker in 10 innings when Marino himself drove in the run he needed to win, 1-0.22

On the year, McCullough was 14-16, posting a 3.10 earned run average in 229 innings. Greenville News sportswriter Carter “Scoop” Latimer called him “the Sally League’s tough luck pitcher this season. He has lost several low-hit games and it is a jinx that pursued him in the Coastal Plain League last year. One of these days, unless expectations go awry, he is going to flash out as a top flight pitcher, and the Washington Senators will be in the right spot to cash in.”23 And as the baseball season ended and Latimer’s thoughts turned to football, he mentioned McCullough as one member of “a corking good six-man football team [which] could be recruited from the Greenville Spinners this year.”24

The Washington Senators were coming off a sixth-place finish in the 1941 American League. Yet, for 1942, manager Bucky Harris faced “the biggest reconstruction job in the majors,”25 having lost steady-hitting shortstop Cecil Travis, two other infielders, two outfielders, and his only left-handed pitcher to the immediate post-Pearl-Harbor military draft. McCullough was invited to spring training in Orlando, and along with the rest of the team, had a solid camp. Now featuring a knuckleball in addition to his fastball and pitching with “a lot of poise,”26 McCullough, targeted for a relief role, was one of 10 pitchers, six of them starters, Harris tabbed to open the 1942 season on his roster.

Strong pitching had carried the Senators through spring training, but Harris’s hopes were dashed as Washington allowed 48 runs in the team’s first eight games and stood 3-5. None of the mound woes could be attributed to McCullough—he hadn’t pitched in a game yet. He got that chance on Wednesday, April 22, as the Senators opened a 15-game homestand on a cold, wet afternoon in Griffith Stadium against the Boston Red Sox. Once again, Washington got in a hole right away, as starter Early Wynn27 yielded four runs and didn’t make it through the first inning. After six innings, Boston led, 9-4. Harris had used three pitchers, and in the Washington bullpen, coach Bennie Bengough “took a brand-new baseball out of his pocket and gave it to me and said ‘You’ve got two minutes to warm up.’ McCullough remembers he replied, “In this weather? I’ll need a stove!”28

The big righty seemed a world-beater in the seventh inning. He struck out the first hitter he faced, Jim Tabor, retired Pete Fox, then fanned future Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr. He ran the string to five consecutive outs in the Boston eighth inning, retiring Johnny Peacock and opposing pitcher Oscar Judd. But now the Red Sox’ batting order rolled over. McCullough allowed his first major-league hit, a double, to Dom DiMaggio. Johnny Pesky followed with a triple, scoring DiMaggio and bringing Ted Williams to the plate. Williams, whose epic .406 batting average the prior season has since been unmatched, had come into the game at .375 in 32 plate appearances for 1942. McCullough bore down and got an out to end the half-inning.

The pitcher’s spot was due up second in the Washington eighth, and now down, 10-4, Harris let his rookie hit. Judd retired him, and McCullough took the mound for the top of the ninth. It didn’t go well, as Tony Lupien worked a walk to open the inning and the Red Sox batted around, scoring three runs on three hits, two walks, and an error. With two outs and the bases loaded, McCullough faced Williams again—not an auspicious situation against a hitter with Williams’s ability to analyze and adjust. But McCullough came through, getting a groundout to second base.

Despite the ups-and-and downs of his debut, McCullough remembers, “I thought, this is going to be good. It was kind of like anything else in life. I made some mistakes, but everybody makes mistakes.”29

Over the next few days, Washington’s starters continued to falter. Harris decided he needed left-handed relief help; rookie righty McCullough was the casualty. The Senators sent him to the Class-A-1 Southern Association Chattanooga Lookouts in exchange for lefty Bill Kennedy.30 With Chattanooga, McCullough returned to a starting role. In his first start for manager Marv “Sparky” Olson, he beat Memphis, 6-3, on a five-hitter, driving in the first Lookouts’ run with a double.31 In June, back in his home territory as the Lookouts visited the Atlanta Crackers at Ponce de Leon Park, McCullough yielded 12 hits and looked to be on the hook for a 4-1 loss until Herb Stein launched a three-run homer on a two-out, 3-2 pitch to tie the game in the top of the ninth inning; Chattanooga then won it, 5-4, for McCullough in the 10th.32 Despite these successes, though, McCullough’s 1942 Chattanooga season was disappointing—an 8-14 record and 4.81 ERA in 28 games—and he was never recalled by Washington.

McCullough and Mary Ruth returned to Atlanta after the 1942 season. He worked in a Hercules Corporation explosives plant, then for a while at his father-in-law’s general store in Alpharetta. Although McCullough was on the Senators’ reserve roster for 1943,33 he expected to be drafted and volunteered for the navy.34 He served in the South Pacific, was in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, and was stationed for “about a year in Alungapu in the Philippines.”35 He was a petty officer in charge of tracking personnel arrivals and departures and handled recreation programs. Carol McCullough remembers her father’s stories about pickup ballgames with Pee Wee Reese and supplying navy undershirts to “bare-chested native women,” who promptly reappeared “wearing the shirts, but with holes cut in them.”36

McCullough was 28 and the Senators still held his baseball rights when he was discharged in November 1945. “He never gave returning to baseball another thought after having been away from the sport for [parts of] three years;”37 the Washington club formally suspended him for failure to report.38 His daughter Carol remembers that he told her his thinking at the time—that pitchers would have more difficulty returning to baseball than hitters and his college education, something most returning ballplayers didn’t have, would help him land fulfilling employment with steady compensation to support his family. The couple moved into Mary Ruth’s family home in Little Five Points, and through his wife’s Sunday school class, McCullough soon met the principal of Boys Special School in the Inman Park neighborhood of Atlanta, which took on at-risk “delinquents, truants, and slow learners”39 from throughout the City of Atlanta school system. He went to work there in January 1946, first as a truant officer, then as an assistant principal, then curriculum officer, then as principal. The school had an annual summer camp for its students in the Blue Ridge Mountains of northeast Georgia. McCullough led the summer sessions for several years while Carol was growing up; she has fond memories of bonding with the camp’s students and staff, who respected and admired her father.40

Although McCullough, an avid reader and journal-keeper all his life, taught classes in creative writing at each of the schools he served, he found a natural fit in administrative work. To further develop his skills in an evolving field, he earned a Master’s degree from Peabody College in Nashville, becoming an early expert in innovative, hands-on curriculum for elementary and secondary schools.41 After leaving Boys Special School, he applied his ideas on curriculum as both an elementary and high school principal at a series of traditional schools in the Atlanta city system. He was a principal during the integration of not only the students but the teachers in the city schools following the mandates of the U.S. Supreme Court in the mid-1950s,42 using individual teachers’ abilities as his governing principle for assignments. “Gregarious and witty,” but with definite ideas on decorum, he campaigned successfully in the early 1970s for changes in the dress code for teachers across the school system when he deemed that eroding standards were having a negative effect on a good educational atmosphere.43

A minor heart attack led to Phil McCullough’s retirement from the Atlanta city schools in 1980 after 34 years of service. He was 63 and continued to do yard work at his suburban Atlanta home and to play catch with his daughter Carol when she visited. This was something they had done from Carol’s early childhood. “I still have my glove,” she says.”44 Phil increased his focus on teaching Sunday school, leading both children’s and adult classes, and gave inspirational talks to church groups. He continued to churn what Carol remembers as his “famous” homemade ice cream, with which he had treated his administrative staff and teachers and now had additional time with which to experiment.45 He went back to the elementary schools as a volunteer, sharing his love of books as a reader for student groups.

Phil had honed Carol’s interest in baseball with reminiscences of his days as a player, their games of catch, family trips to spring training while she was growing up, old-timer’s reunions, and Atlanta Crackers’ games at Ponce de Leon Park. In his early years with the Atlanta schools, he did some pitching for Candler Park teams in the Georgia Amateur Baseball League.46 With baseball fans all across the Southeast, he and Carol welcomed the arrival of the Atlanta Braves from Milwaukee in 1966 and occasionally saw them play at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. When what later became Atlanta’s Turner Field was built for the Olympic Games in 1996, he wanted to see it, and Carol obliged him, although she recalls he preferred “the smaller, older parks.” She recalls that Phil’s special favorite among Braves players was shortstop Walt Weiss,47 “because he was scrappy,” but she and her dad also loved to watch first baseman Chris Chambliss. Carol remembers her dad had “great respect” for Hank Aaron, not just as a home run legend, but for his durability and the statistics he accumulated over a long career.48

When Mary Ruth passed away in the fall of 1998,49 Phil, then 81, briefly lived alone; then, his mobility limited by arthritic knees and a decision he made himself that he should no longer drive, he moved to a senior living facility, Arbor Terrace, in Decatur, an Atlanta suburb. He donated his extensive personal library—with substantial collections on Bible studies, inspirational works, and the American Civil War—to Arbor Terrace and started a library, then a reading group, for his fellow residents.

“Sharp to the end,” the man who had pitched in only one major-league game but had retired Ted Williams twice passed away in his sleep at Arbor Terrace on January 16, 2003, as many avid readers might hope to do—“leaned back in his desk chair with his feet up and with a book in his lap.” He was 85 and was survived by his daughter, Carol.50

Phil McCullough’s lasting impact on education in Atlanta was made evident when “teachers from years back” honored him with attendance at his memorial service in Alpharetta.51

Acknowledgments

This biography arises from a chance remark about writing baseball history for SABR I made at a meeting of a monthly book group sponsored by the Transylvania County (NC) Library. Another member of the group, new to our area, came up to me after the meeting and said excitedly, “My dad played professional baseball and taught me a lot about the game. I’ve been a fan all my life.” I learned she was Carol McCullough, Phil McCullough’s daughter. Since that chance meeting, we’ve worked together to make her father’s story part of the SABR Baseball Biography Project archive. Because Phil McCullough was a one-game player, Richard Tellis’s profile provided a valuable starting point, and both Carol and I are grateful that he was able to interview Phil before the latter passed away in 2003. Carol McCullough and I hope her enthusiastic recounting of family history and her treasured memories of her father have helped this effort enrich what Richard Tellis thoughtfully started.

Reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Photo credit

Carol McCullough provided the original of what she says her dad always called “my baseball card picture.”

Sources

My conversations and e-mail correspondence with Carol McCullough were invaluable to fill in gaps that a project such as this entails. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, major and minor league team and season pages, and batting and pitching logs. I accessed McCullough family information through Ancestry.com at the Transylvania County (NC) Library. All cited newspaper articles were accessed through either Newspapers.com or The Sporting News, via Paper of Record.com, provided with SABR membership. My SABR colleague Kevin Larkin reviewed and sent me material from Phil McCullough’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Richard Tellis, Once Around the Bases: Bittersweet Memories of Only One Game in the Majors (Chicago: Triumph Books, 1998), 54.

2 Ibid, 55.

3 An internet photo of Phil McCullough’s grave marker in Rest Haven Cemetery, Alpharetta, Georgia, shows the identifying engraving as “PHIL (PINSON LAMAR) McCULLOUGH.” Phil McCullough entry, Billion Graves.com, accessed March 14, 2018; Carol McCullough conversation with author, April 18, 2018.

4 Carol McCullough’s first name in Phyllis. “I looked like Daddy and was called “Little Phil” from time to time as a kid, she remembers. Carol McCullough e-mail, May 23, 2018.

5 Tellis, 51.

6 Although it was close to home, McCullough considered Oglethorpe “an outstanding baseball school.” Ibid. Future Baseball Hall of Famer Luke Appling had played there in 1929 and 1930. Oglethorpe University entry, Baseball-Reference.com Schools Index, accessed March 14, 2018.

7 Tellis, 51.

8 “Dean of Petrels, Hurls No-Hitter,” Atlanta Constitution, May 19, 1936: 16.

9 “Petrels Face ‘Gator Nine Today,” Atlanta Constitution, May 5, 1937: 10.

10 “Nine Gridders on Honor Roll At Oglethorpe,” Atlanta Constitution, May 21, 1938: 16.

11 Oglethorpe University Athletic Hall of Fame entry, GoPetrels.com, accessed March 7, 2018.

12 Tellis, 52.

13 Ibid. Tellis quotes McCullough as citing the pay as weekly. Given the times and the level of play, the $147 was almost certainly a monthly rate. Carol McCullough remembers her father telling her that his “signing bonus” was a team warmup jacket. He also told her that teammates and fans quickly started to call him “Big Bear,” based on his size and the team’s name.

14 Tellis, 52.

15 Jake Strother, “Burying of Hatchet Features New Bern Opener in Kinston,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1940: 5.

16 Jake Strother, “Sothern Out As Kinston Pilot; Pitcher Averette Put in Charge,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1940: 7.

17 Undated handwritten recollection by Phil McCullough in Phil McCullough file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Subsequent research shows that McCullough’s memory was faulty. He had recalled a two-hitter and an unearned run. But he did “pitch hitless ball until the sixth” in that game, played August 5, 1940. See: “Greenies Top Eagles In One-Run Struggle,” News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), August 6, 1940: 10.

18 Jake Strother, “Kinston Personnel Stripped By Sales and Dozen Recalls,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1940: 5. Still in extensive use in the minor leagues to determine divisional and league champions, a typical Shaughnessy system matches the first- and fourth-place teams and the second- and third place teams in the regular season standings in separate semi-finals, then matches the winners in the finals. The 1940 Coastal Plain League finals were a best-of-seven series.

19 The Sporting News, September 11, 1941: 84.

20 Carter Latimer, “Erratic Throwing Handicaps Both Teams in See-Saw Affair,” Greenville News, May 20, 1941: 9.

21 “McCullough Pitches, Bats Brittain Club to Victory,” Greenville News, May 25, 1941: 17.

22 “Marino’s Hit Scores Winning Run in Extra-Inning Battle,” Greenville News, August 20, 1941: 10.

23 Carter Latimer, “Scoopin’ ‘Em Up” column, “McCullough Is Jinxed Again,” Greenville News, June 28, 1941: 7.

24 Carter Latimer, “Scoopin’ ‘Em Up” column, “Star Gridders Among Spinners,” Greenville News, September 10, 1941: 8.

25 Dillon Graham, Wide World Features, “Think Your Job Is Tough?” Star Press (Muncie, IN), April 2, 1942: 10.

26 Shirley Povich, “Nats All Peaches in Grapefruit Loop,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1942: 14.

27 Wynn was 22 years old and had pitched in a total of eight games for Washington in 1939 and 1941 when he opened the 1942 season as part of the starting rotation. He went on to win an even 300 major-league games and was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1972.

28 Tellis, 54

29 Ibid, 55.

30 “Lookouts Get Phil McCullough,” Greenville News, April 25, 1942: 9.

31 “Chattanooga Defeats Chicks,” Monroe (LA) News-Star, April 30, 1942: 7.

32 Jack Troy, “Stein’s 3-Run Homer in 9th Ties Game, 4-4,” Atlanta Constitution, June 11, 1942: 16.

33 The Sporting News, January 7, 1943: 2.

34 By April 1943, when the baseball season opened, McCullough was on Washington’s National Service List. The Sporting News, April 22, 1943: 3.

35 Tellis, 57.

36 Carol McCullough conversation, April 18, 2018.

37 Tellis, 57

38 Note dated April 3, 1946, in Phil McCullough Hall of Fame file.

39 Tellis, 57.

40 Carol McCullough conversation, April 18, 2018.

41 Such an approach is known today as “experiential education.”

42 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); 349 U. S. 294 (1955). The latter decision added an element of “with all deliberate speed” to the original integration mandate. Atlanta integrated its schools in 1961. Although delayed, the Atlanta integration was done peacefully and was commended by President John F. Kennedy as having taken place “with dignity and without incident.” Atlanta Magazine.com, August 1, 2011, accessed May 7, 2018.

43 Carol McCullough conversation, April 18, 2018.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Atlanta Constitution, June 11, 1951: 8.

47 Walt Weiss played the last three seasons (1998-2000) of his major-league career with the Braves. He managed the Colorado Rockies from 2013 through 2016. In November 2017 he was named Braves’ bench coach under manager Brian Snitker.

48 Carol McCullough conversation, April 18, 2018.

49 Phil and Mary Ruth had been married 59 years.

50 In 2007, Carol McCullough, herself a career educator, married David Messer, a retired college professor. David’s four grandchildren keep things lively for the couple. Carol McCullough conversation, May 8, 2018.

51 Carol McCullough conversation, April 18, 2018. There were services at the Turner Funeral Home in Decatur and graveside at Rest Haven Cemetery, Alpharetta. See: Note 3.

Full Name

Pinson Lamar McCullough

Born

July 22, 1917 at Stockbridge, GA (USA)

Died

January 16, 2003 at Decatur, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.