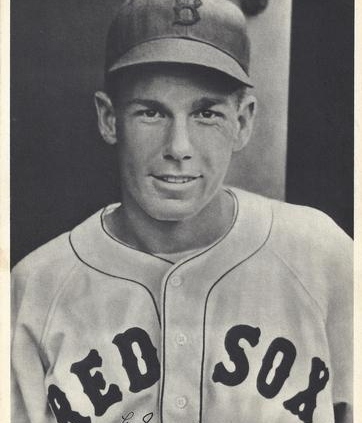

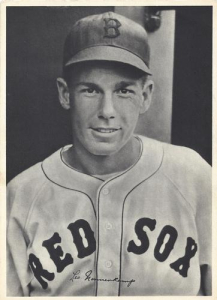

Red Nonnenkamp

Red Nonnenkamp had to wait 1,702 days after his first major-league game to get his first base hit. After his September 6, 1933, debut with Pittsburgh in which he pinch-hit unsuccessfully, Leo came through on May 6, 1938 with his first big league safety. Nonnenkamp, in his 12th appearance for the Boston Red Sox, singled off St. Louis Browns pitcher Bobo Newsom in a 7-3 Sox victory. Nonnenkamp got a chance to play in other than a pinch-hitting or pinch-running role, after regular Sox right fielder Ben Chapman was suspended. Leo took advantage of his opportunity and finally put some numbers up in the hits column.

Red Nonnenkamp had to wait 1,702 days after his first major-league game to get his first base hit. After his September 6, 1933, debut with Pittsburgh in which he pinch-hit unsuccessfully, Leo came through on May 6, 1938 with his first big league safety. Nonnenkamp, in his 12th appearance for the Boston Red Sox, singled off St. Louis Browns pitcher Bobo Newsom in a 7-3 Sox victory. Nonnenkamp got a chance to play in other than a pinch-hitting or pinch-running role, after regular Sox right fielder Ben Chapman was suspended. Leo took advantage of his opportunity and finally put some numbers up in the hits column.

Once Nonnenkamp got going, he put together a fine year, batting .283 for Boston. It was the best in a career that saw him hit .262 in 263 at-bats and drive in 24 runs.

Leo William Nonnenkamp was born in St. Louis on July 7, 1911, the only son of John Theodore Nonnenkamp (1877-1960) and his wife, Elizabeth Kruse Nonnenkamp (1881-1968.) He had two older sisters: Florence (b. 1906) and Lillian (b. 1909). Leo’s father, John, had three brothers and four sisters. Leo’s great-grandfather Joseph Nonnenkamp was born in Germany, near Hannover, and immigrated to the United States through the port of New Orleans, settling in St. Louis.

Leo picked up the nickname “Red” at some point along the line. He never played baseball in school and first played semipro baseball, at the age of 18, in the St. Louis Muny League in the summer of 1929. His .521 average earned him an invitation to join the St. Louis Cardinals’ baseball school at Danville, Illinois. It wasn’t a very exclusive invitation; the April 10, 1930, Sporting News reported that a full 50 rookies had already been released “but there are still enough newcomers present.” Nonnenkamp rated a headline on a brief page five story, the left-handed left fielder dubbed “one of the outstanding rookies in the camp.”

After further evaluation at Springfied, he was signed to a contract and assigned to the Waynesboro Red Birds in the Blue Ridge League, playing Class D ball in Branch Rickey’s burgeoning farm system. Leo hit .297 over the course of 114 games, before the Red Birds lost the best-of-three league playoffs. Nonnenkamp went through a couple of affiliate transactions during the offseason, on the roster of Houston and then Springfield, but by the time 1931 began he’d been advanced to Class C, playing in Pennsylvania’s Middle Atlantic League for the Scottdale Cardinals. He was also on the roster of what he called a “traveling team” – Altoona, an independent team which began the season in Jeanette, moved again and became the Beaver Falls Beavers in the same league. He hit for an identical .297 average, this time hitting 10 homers as opposed to the two he’d hit the year before.

Sometime in the offseason of 1931-32, Nonnenkamp became part of the Pittsburgh Pirates system and was given a ticket to Tulsa in 1932, jumping to the Class A Western League. The Tulsa Oilers must have been glad to have him since he was hitting a spectacular .391 over his first 16 games when he broke his ankle sliding in an early May game and was forced to miss the rest of the season. He read in the newspapers of the Oilers’ win in the league championship. He began 1933 with Tulsa (now in the Texas League) and was hitting .271 after 29 games but the Oilers needed some right-handed hitting and he was asked to go to El Dorado, Arkansas. Not surprisingly, he did better for the Class C Dixie League El Dorado Lions, batting .336 in 63 games and driving in 49 runs. He was rewarded with a late-season call-up to the big-league club, but with Paul and Lloyd Waner and Freddie Lindstrom (three future Hall of Famers) in the Pittsburgh outfield and with the Pirates hoping to secure second place, he did not get much playing time.

The one chance Red got in three weeks with the ballclub was at the plate when manager George Gibson asked him to pinch-hit for pitcher Bill Swift in the bottom of the ninth of the September 6 game. The Pirates were losing, 9-1, to the Giants and there was nothing happening. Hal Schumacher struck Leo out. Red had to wait more than four years to get his next major league at-bat.

The Pirates optioned Nonnenkamp to Little Rock (Class A) for the next couple of years. The 1934 Travelers finished in last place, but Red hit a respectable .278 over his 141-game season. Once again, he hit for the same average two years in a row, posting a .278 average in 1935, too. He seemed to suddenly find some speed in ‘35, leading the Southern Association in stolen bases with 36, four times as many as he’d stolen the year before. He developed a strong reputation as a patient hitter, drawing more than his share of bases on balls. Red played with Little Rock in 1936 and 1937 as well, hitting .326 and .332 respectively. Little Rock had meanwhile become a Boston Red Sox farm team, continuing in 1937 under manager Doc Prothro. Pittsburgh was out of options by this time and so had sold his contract outright to Little Rock. Prothro got Nonnenkamp to stop wiggling his bat while at the plate, and it made a difference. Nonnenkamp was voted MVP of the Southern Association in 1936, though the team still finished 17 games out of first place.

In 1937, the New York Times took note when Nonnenkamp won an exhibition game against the world champion New York Yankees with a two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth inning, to give Little Rock a 9-8 win. The home run snapped a 13-game Yankees winning streak. The paper noted Nonnenkamp as a “popular hero here,” adding, “His mates mobbed him as he reached the plate.” By August, The Sporting News predicted that he had a chance to make the Red Sox the following year. The Travelers led the league in 1937 and beat New Orleans in the playoffs; Red led the league in runs scored, with 145. The Sporting News reported in October that Nonnenkamp was the unanimous choice as the league’s Most Valuable Player. The Red Sox were ready. And so was Red; after four years with Little Rock he was nonetheless “an incurable optimist, with a winning smile and a contagious laugh, believing that the service in the minors has done him a lot of good” – in the words of Edgar G. Brands, editor of The Sporting News.

During 1938 spring training the New York Times noted that Nonnenkamp’s “lighting speed … brought a smile to [Tom] Yawkey’s face” and a little power didn’t hurt, either – the home run he hit over Sebring’s right-field wall against the Newark Bears was said to be only the second to leave the ballpark over the 350-foot barrier; Lou Gehrig hit the other two years before. Nonnenkamp made the big-league club, and Ted Williams did not. Williams was sent to Minneapolis for more seasoning; Nonnenkamp joined the Red Sox as fourth outfielder behind Ben Chapman, Doc Cramer, and Joe Vosmik.

Leo traveled north with the ballclub and first saw action in Boston during the first of two City Series games in the Hub against the Boston Bees. He was asked to pinch-hit, but failed to connect. On Opening Day, Leo had another opportunity, batting for Jim Bagby in the sixth inning. He walked to load the bases and scored on Doc Cramer’s single, part of a six-run sixth. But then he appeared in nine ballgames (eight as a pinch-hitter and one as a pinch-runner) before he finally got his first major-league hit.

On May 5, Ben Chapman and Detroit’s catcher Birdie Tebbetts tangled at the plate. Chapman, the Red Sox right fielder, drew a three-day suspension. Leo filled in for the final four innings of the May 5 game, going 0-for-2 but collecting his second RBI. The next day he started his first game and went 2-for-5 in a 7-3 win against the Browns at Fenway Park. He had two singles, drove in one run and scored another, and even threw a runner out at the plate for a double play. Fielding was a bit of a forte for Nonnenkamp. In an August 1938 clipping found in his Hall of Fame player files, sportswriter Vic Stout wrote, “Leo would much rather tear around the outfield chasing flies. In fact, Nonnenkamp is so wrapped up in his fielding that Manager [Joe] Cronin has to keep after him to get him up to the plate in batting practice.”

On May 7, Leo was 1-for-3, a triple, scoring one run and driving in another. On May 9, though just 1-for-3, he scored three times and drove in one. After Chapman returned to the lineup, it remained a tough outfield to crack but Leo got into 87 games for a total of 180 at-bats and hit .283 with 18 RBIs. The triple on May 7 was his only one of the year; he had four doubles but never hit a major-league home run.

A 3-for-5 game on June 2 and his 12th-inning game-winning single on July 30 were a couple of highlights of his season. After the season, Boston traded Ben Chapman to Cleveland for Denny Galehouse and Tommy Irwin (and secured Elden Auker and Jake Wade in another trade). Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich speculated that either Nonnenkamp or Fabian Gaffke would take over right field for the Red Sox. It was a rare lapse of forgetfulness for the usually solid sportswriter; he’d somehow forgotten that the kid who had won the Triple Crown in the American Association was the heir apparent: Ted Williams. There was no way to deny The Kid. He had a lock on right field. Nonnenkamp and Gaffke were outfield backups. Red, with his .300 average in pinch-hit duties, was kept on the team and Gaffke was the one sent to Louisville on option at the end of April.

Gaffke got into just one game in 1939, but Nonny accumulated 75 at-bats in 58 games, hitting .240. He drove in only five runs, but filled in as needed. Williams had an excellent year, his 145 RBIs setting a rookie record that has yet to be topped.

Leo didn’t know it yet, but the handwriting was on the wall. His major-league career was almost over. The Red Sox had another couple of other outfielders coming up in their system: Dominic DiMaggio and Stan Spence. They’d purchased Lou Finney from Philadelphia early in 1939, and with Finney in right, Cramer in center, and Williams moving to left field, all three Sox regular outfielders hit over .300 in 1940. Nonnenkamp nonetheless trained with the team in spring training and even featured in a minor news story on April 5. During an exhibition game against Cincinnati in Greensboro N.C., with the score 12-10 in favor of the Reds, Red fouled an eighth-inning pitch out of Memorial Park. There simply were no more baseballs left with which to play. The game had begun with 96 baseballs available, but every one of them had been lost to fans in the stands or outside the ballpark. The game ended and Cincinnati won, with Nonnenkamp still at bat. Newspaper readers in Florence S.C., the next morning might well have recalled the day precisely one year earlier when the two teams met the same fate in their town. On April 6, 1938, the game was called off with the score 18-18. That was quite a wild affair, too, but played with only four dozen balls. Doubling the number on hand hadn’t spared them living out a bit of déjà vu.

Nonnenkamp’s 1940 was even more frustrating than 1939. Red played in only nine games for the Red Sox during April and May, exclusively as a pinch-hitter. He was officially 0-for-7, was hit by a pitch once, and drove in his final run in major-league ball with a sacrifice fly to right field in the 11th inning of the May 11 game at Yankee Stadium. He drove in Jim Tabor from third, giving the Red Sox an 8-7 lead. Fortunately, Finney doubled and Cramer singled to give the Sox an insurance run. The Yankees scored once in the bottom of the inning.

On June 6, the Red Sox optioned Nonnenkamp to Louisville and brought up Stan Spence. Before the end of the month, Louisville had in turn sent Leo to Newark, with which, though it was a Yankees farm club, they apparently had a bit of an understanding. The Bears were desperate for an outfielder and the Colonels needed an infielder, so the Bears swapped Jim Shilling to Louisville. Nonnenkamp had hit .294 for Louisville, albeit in only 17 at-bats, but got more play in Newark. He felt that Johnny Neun was the best manager he’d played under. On August 27, it was announced that Nonnenkamp was to be brought back to the Red Sox when the rosters expanded in September, but on September 11, the Red Sox sold his contract outright to Newark. The International League season was still under way. By year’s end, Red had hit .280 in 143 at-bats, and he helped the Bears win the Little World Series, beating – ironically – Louisville in six games, his sixth-inning single plating the game-winning run of the 6-1 victory.

Newark had Nonnenkamp for the entire 1941 campaign and he hit .301 with eight homers and 54 RBIs. His pinch-hit ninth-inning homer on May 6 beat the Rochester Red Wings. A three-hit game against Buffalo on July 11 and another three-hit game that included a pair of home runs on the 15th against Baltimore were big days in a torrid first half of July. His hitting through the rest of the year wasn’t quite as spectacular. Early in 1942, the Kansas City Blues bid for his services and Leo joined the American Association in exchange for Bud Metheny. The move was prompted by new K.C. skipper Johnny Neun, who’d managed Leo in Newark. Neun was known to remain impressed with his strong arm as a fielder. He had a subpar season at the plate, though, batting just .227 over the course of 153 ballgames.

In the spring of 1943, Nonnenkamp was taken into the Navy, and right after finishing boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Training Station found himself playing for Mickey Cochrane’s famous Great Lakes team. Cochrane had Leo lead off in a benefit exhibition game when Great Lakes visited Kansas City and played the Blues. Leo got two hits, but the Blues won the game, 1-0.

Nonnenkamp served in the Navy for the duration, stationed on New Caledonia in the Pacific for 1944 and 1945. He missed three seasons of pro ball, and returned with the Little Rock Travelers in 1946. It was his final year. He hit .231 in 65 at-bats and was finally released after 22 games, on May 13, the same day the Travs released Daffy Dean. The Travelers had him help run their baseball school in March, but this was the end.

Leo stayed on in Little Rock. While with the Red Sox, he had married Little Rock’s Jill Young. The couple had no children, but they loved living in Little Rock and made it their lifelong home. “You could visit folks and not spend most of the evening traveling to get there,” he told an interviewer. “You didn’t have to lock your car and you could go fishing. It was more like living than in the big city.” He was apparently an excellent local bowler. His wife, Jill, preceded him in death. The two were members of Holy Souls Catholic Church.

Nonnenkamp worked for many years as a post office mail carrier. Leo was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in February 1993. He died at 89 on December 3, 2000.

Sources

Interviews with Marc E. Nonnenkamp, Don Nonnenkamp, Tommy Beck, Neil Dobbins, Jim Rasco, Danny Shameer, and Todd Traub, all in May 2007.

Traub, Todd. “Nonnenkamp’s HR memorable” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 31, 2006

Leo Nonnenkamp player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Leo William Nonnenkamp

Born

July 7, 1911 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

December 3, 2000 at Little Rock, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.