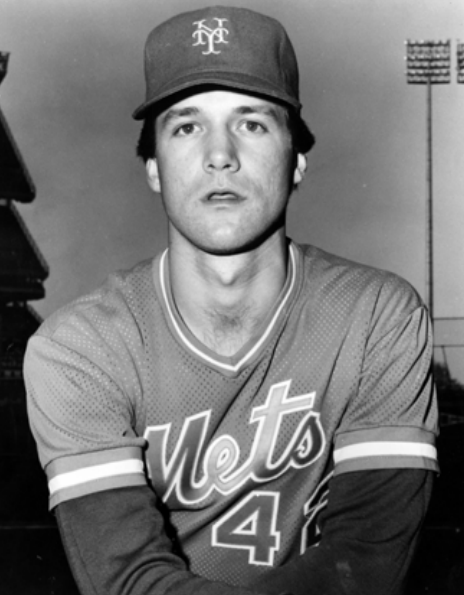

Roger McDowell

Roger McDowell kept his locker stocked with comedy props, costumes, and fireworks, blew bubbles while he pitched, played the notorious “Second Spitter” on Seinfeld and was known to set teammates’ shoes on fire. But he knew a little about pitching too.

McDowell racked up 70 wins and 159 saves pitching almost exclusively in relief over a 12-year big-league career, highlighted by a win in the decisive Game Seven of the 1986 World Series. After his playing career he rapidly ascended as a pitching coach, and as of 2015 had held that role with the Atlanta Braves for 10 years and counting.

Roger Alan McDowell was born on December 21, 1960, in Cincinnati, the youngest of Herb and Ada McDowell’s three children. He graduated from Cincinnati’s Colerain High School in 1979 and attended Bowling Green State University on a baseball scholarship, arriving on campus shortly after Orel Hershiser, a 17th-round pick of the Dodgers in the 1979 June draft, departed. Both pitchers were recruited to Bowling Green by coach Don Purvis, a one-time pitcher in the Yankees’ system.

McDowell, who studied commercial art in college, selected Bowling Green over a rival offer from Virginia Military Institute. He led the Falcons with a 5-4 record during his junior year, earning All-Mid-American Conference honors, and was selected by the Mets in the third round of the 1982 draft.

A slender right-hander listed at 6-foot-1 and 175 pounds, McDowell made his living on essentially one pitch — a sinking fastball that he could throw at various speeds, almost always for strikes. He said in 1985 that he’d developed the pitch in high school. “I just throw it down the middle knee-high, and it drops late,” he told the New York Times.1 McDowell also threw a hard slider and an occasional changeup, but his sinker, augmented by his good control, was his featured delivery. “He never shakes me off,” Gary Carter, his catcher with the Mets, remarked. “There’s nothing to shake off, actually. He just throws the one pitch.”2

McDowell made his professional debut at age 21 for the Shelby (North Carolina) Mets of the South Atlantic League in 1982, going 6-4 in 12 games (11 starts) before getting a promotion to Lynchburg (Virginia) of the Carolina League, where he was 2-0 with a 2.15 ERA in four starts. In 100⅔ innings for both teams, he allowed just one home run.

A year later, in 1983, McDowell’s career was nearly over. An 11-12, 4.86 season for Jackson of the Double-A Texas League was cut short when he began to suffer elbow pain. When months of rest failed to cure him, McDowell underwent surgery in February of 1984. Mets doctor James C. Parkes removed bone chips and spurs.

Recovery limited McDowell to just 7⅓ innings for Jackson in 1984 plus another 14 in the playoffs, but during a postseason stint in the Instructional League, McDowell rediscovered his signature sinker and a little something extra. Augmented by a slight adjustment in arm angle, giving him a three-quarters delivery, McDowell found that his sinker broke even more sharply than the one he threw before the injury.3

McDowell’s work in the Instructional League caught the eye of Mets manager Davey Johnson, who invited him to spring training in 1985 and surprised many by selecting him to go north with the team when camp broke. McDowell, who had a 2.28 ERA that spring, got the nod over incumbent sinkerballer Doug Sisk, who had struggled with injuries and control problems and began the year in Triple-A Tidewater.

McDowell made his major-league debut on April 11, 1985, pitching a hitless, scoreless top of the 11th inning against the St. Louis Cardinals at Shea Stadium, preserving a 1-1 tie. The Mets scored in the bottom of the inning, and he got the win. McDowell made two ineffective spot starts in late April and early May — they would be the only two starts among his 723 big-league appearances — but by midseason he’d established himself as a late-inning weapon in New York’s bullpen, and his sinker was the talk of the league.

“He’s got a wicked sinkerball. I know it, and so do other hitters,” Keith Hernandez said. “They come down to first and talk to me about the kid’s nasty sinker. He is awesome.”4

Ken Landreaux of the Los Angeles Dodgers described facing McDowell’s sinker: “The ball is right here,” Landreaux insisted, holding his hand chest-high. “You see it so clearly you think you’ll get it on the fat of the bat. Then, all of a sudden, poof! It’s gone. Goodbye.”5

McDowell went 6-5 with 17 saves and a 2.83 ERA in 1985, and finished sixth in the Rookie of the Year voting.

Though a 1985 New York Times article described him as “a mild-mannered, laid-back, inoffensive and polite young man,”6 as McDowell’s success continued, his confidence grew and a colorful personality emerged. McDowell wore a spiky haircut, often covered by a cap worn backward, and was generally spotted working a thick wad of pink bubble gum, which he took up chewing as an alternative to tobacco. There was a hint of innocent mischief in his countenance.

In 1986 McDowell’s reputation as a fun-loving prankster became legendary. On a team with no shortage of style and swagger, McDowell stood out as the class clown. His specialty was in giving unsuspecting teammates a “hotfoot” — McDowell would use bubblegum to wrap a book of matches around a cigarette, secure it to the heel of his victim’s baseball shoes with tape, then light the cigarette. When the cigarette ash reached the matches, the pack would ignite, sending flames up the pant leg of the victim.

McDowell performed the stunt dozens of times in his career and despite the elaborate nature of the trick — securing and igniting the device often meant crawling beneath a dugout bench undetected — he was never caught in the act. His favorite victim was Bill Robinson, the team’s hitting coach.

McDowell was also known for boyish stunts providing unexpected laughs or commentary on the game:

- When the Mets honored retired star Rusty Staub in 1986 in a pregame ceremony, a contingent of teammates led by McDowell emerged from the dugout to present Staub a plaque — each wearing a garish red wig that McDowell had supplied.

- Before a game in Los Angeles in 1987, McDowell appeared on the field wearing his uniform upside-down, pants stretched over his head and shoes on his hand.

- Also in 1987, he made light of an administrative crackdown on ball doctoring by conspicuously wearing a carpenter’s belt in the bullpen, complete with lubricant, sandpaper, a file, and a chisel.7

- If there was a slumping hitter in the lineup, McDowell could be counted on to toss a lit pack of firecrackers into that player’s slot in the bat rack.

- He once got the attention of fans seated around the visiting bullpen at Dodger Stadium, then threw open a door to reveal teammate Jesse Orosco seated on the toilet.8

- McDowell took pride in his assertion that he could eat more than any of his teammates. When presented with 3,500 pieces of bubble gum in April of 1988 as a thank-you for a charity donation, he quipped, “This should last me till June.”9

- When Tommy Greene threw a no-hitter against the Expos in 1991, McDowell fooled his Phillies teammate with a fake congratulatory phone call from Brian Mulroney, the prime minister of Canada. “It was a tossup who was fooled more that day, the Expos batters or Greene, who carried on a lengthy conversation with the phony Mulrooney,” writer Paul Hagen observed.10

Despite the reputation for goofiness on the sidelines, McDowell was “all business on the mound,” in the words of teammate Gary Carter.11 In 1986 he was 14-9 with 22 saves. His victory total that year still stood in 2015 as a record for a Mets reliever, and his 75 appearances that year set a since-broken club record. His 22 saves were one more than left-hander Jesse Orosco for the club lead in ’86.

Though they split saves and save opportunities nearly down the middle, McDowell and Orosco tended to be employed differently by Johnson in 1986. While the manager used Orosco primarily as a short reliever (58 appearances), he called on McDowell for all kinds of assignments, citing his ability to throw strikes and his durability. McDowell averaged more than five outs per appearance in 1986. “I’m aware of how much I use him but you can abuse a sinkerball pitcher like Roger,” Johnson said. “The more he’s used, the more his ball sinks.”12

The ’86 Mets were a swaggering, powerhouse club with a tremendous will to win. McDowell embodied that spirit in a 14-inning affair on July 22 in Cincinnati, a game in which both clubs emptied their benches, in part due to ejections after a 10th-inning brawl between the Mets’ Ray Knight and the Reds’ Eric Davis. The shortage of players forced Johnson to swap Orosco and McDowell between outfield positions and the pitcher’s mound for four innings, with McDowell eventually recording the win.

In the postseason the Mets’ dual closers teamed for another white-knuckle win, eliminating the Houston Astros in Game Six of the National League Championship Series. In that game, a 4 hour 42 minute, 16-inning affair at the Astrodome, McDowell contributed five innings of scoreless relief after the Mets tied the game 3-3 with a two-run ninth-inning rally before turning the game over to Orosco, who blew a 4-3 lead in the 14th but held on despite a two-run Houston rally in the 16th to preserve a 7-6 win.

McDowell appeared in five of the seven games of the Mets’ triumphant 1986 World Series, including Game Seven, when he was the beneficiary of the Mets’ tiebreaking three-run rally in the seventh inning, earning the victory despite giving two of those runs back in the eighth.

The heavy workload of 1986 may have come at a price; McDowell missed the first six weeks of the 1987 season after surgery for a hernia. He returned in time to again lead the Mets with 25 saves that year, although his ERA climbed more than a full run, to 4.16 from 3.02 in 1986, accompanied by an increase in home runs per inning and a decrease in strikeouts per inning. Facing a barrage of injuries that year, the Mets failed to defend their Eastern Division title, finishing three games behind the St. Louis Cardinals.

The Mets regained that crown in 1988 with a 100-win season helped in part by a return to form by McDowell, who went 5-5 with 16 saves despite surrendering the role of primary closer to young fireballer Randy Myers. In 89 regular-season innings, McDowell allowed just one home run, but in the NLCS, a resounding blast to right-center by the Dodgers’ Kirk Gibson off him in the 12th inning of Game Four was a key moment in the Dodgers’ seven-game series win. McDowell hardly ever gave up home runs. (As a witness, the author was shocked. “Stunning” if you prefer?)

The 1989 Mets got off to a poor start, losing seven of their first 10 games. Struggling to stay above .500 on June 18, they traded McDowell, outfielder Lenny Dykstra and a player to be named (reliever Tom Edens) to Philadelphia for infielder-outfielder Juan Samuel. The trade was announced shortly after the two teams completed a game that afternoon.

The deal turned out poorly for the Mets — they traded the disappointing Samuel after the season — while in Dykstra, Philadelphia acquired a key figure in their 1993 pennant-winning squad. (Philadelphia the same day acquired pitcher Terry Mulholland, a key starting pitcher for the 1993 squad, in a separate trade with the Giants.) McDowell had a brief renaissance with the Phillies, allowing just one unearned run in his first 20 appearances and finishing with a 1.11 ERA and 19 saves. One of those saves came against the Mets at Shea Stadium on September 27 and ended with a brawl between McDowell and Mets infielder Gregg Jefferies. The fight appeared to have been sparked by words exchanged between McDowell and Jefferies as Jefferies ran out a game-ending grounder to second base. “Gregg’s been through some tough times this season. There’s been a lot of pressure on him and maybe it all got to him,” McDowell remarked afterward. “I never disliked him, but I don’t think we’ll be exchanging Christmas cards this year.”13

McDowell signed a three-year contract with the Phillies after the season and in 1990 he led the National League with 60 games finished while recording a team-leading 22 saves.

McDowell lost the closer role to newly acquired Mitch Williams in 1991 and was traded to the contending Dodgers for outfielder Braulio Castillo and reliever Mike Harkey on July 31. McDowell had a 2.55 ERA in 33 appearances down the stretch but the Dodgers finished one game short of Atlanta for NL West crown.

McDowell stayed with the Dodgers through 1994, enduring lean years for the team, including a last-place finish in 1992 when he led the club with 14 saves and posted a 4.09 ERA, his highest mark since 1987’s 4.16.

In 1995 the 34-year-old McDowell signed with Texas for $500,000. “Let’s face it — it’s not like they signed Christy Mathewson,” he remarked — and went 7-4, 4.02 in 64 appearances in middle relief.

McDowell signed with the Orioles in 1996. He was reunited with former manager Davey Johnson, who used him as set-up man for his former teammate Randy Myers as closer. As he had done a decade earlier, Johnson relied heavily on McDowell — he was among the league leaders in appearances before soreness in his 35-year-old shoulder sidelined him in July. He returned briefly in August before again going to the disabled list, ending his season and proving to be his last appearances in the majors.

McDowell signed with the White Sox in 1997 but two shoulder surgeries prevented him from making any appearances that year. He attended spring training again with Chicago in 1998 but announced his retirement after pitching a single inning in spring training. He accepted an offer to tutor some young prospects for the organization.

He retired with a career record of 70-70, with 159 saves and an earned-run average of 3.30. His groundball to fly ball ratio of 1.69 was about twice the league average during his career. (Baseball-reference does not include data on that stat prior to 1988.)

McDowell, who parlayed his prankster reputation into appearances on MTV’s “Rock n’ Jock” softball games in the early 1990s, gained still more notoriety for an appearance on an episode of the TV comedy Seinfeld. Airing for the first time in February of 1992, “The Boyfriend” also starred McDowell’s one-time teammate Keith Hernandez in a send-up of conspiracies around the Kennedy assassination. (McDowell told an Atlanta radio station that he continued to get a royalty check for $13.52 each time the episode aired.)

McDowell resumed his career as a pitching coach in 2002 and 2003 with the South Georgia Waves, a Class-A South Atlantic League affiliate of the Dodgers, who promoted him to oversee pitchers at Triple-A Las Vegas in 2004 and 2005.

Calling McDowell “one of the true up-and-coming teachers of the game,” Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox chose McDowell to succeed longtime pitching coach Leo Mazzone in Atlanta beginning in 2006.14

The Braves ranked fifth or better in the majors in ERA for six straight seasons (2009-2014) under McDowell, whose pupils included Craig Kimbrel, Jair Jurrjens, Javier Vazquez, Jonny Venters, Julio Teheran, Kris Medlen, and Brandon Beachy. McDowell kept a low profile, particularly after getting a two-week suspension in 2011 for what league officials called “inappropriate comments and gestures” while responding to hecklers in San Francisco.

As of 2015 McDowell lived in Marietta, Georgia, near Atlanta, with his wife, Gloria, and their two daughters. He has a son, Logan, from a prior marriage.

Sources

In addition to the works cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following sources:

Ultimatemets.com.

Baseball-reference.com.

scouts.baseballhall.org.

mgrittani.wordpress.com.

New York Mets 2015 Media Guide, mlb.com.

Atlanta Braves 2015 Media Guide, mlb.com.

Youtube.com.

Notes

1 Joseph Durso, “McDowell’s Success a Tribute to Faith,” New York Times, June 2, 1985.

2 Ibid.

3 Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won! (New York: HarperCollins, 2004).

4 Jack Lang, “McDowell Is Mets’ Latest Rookie Find,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1985.

5 Mike Geffner (Associated Press), “Roger McDowell Has Filled a Void on Mets’ Roster,” Newburgh (New York) Evening Journal, June 30, 1985.

6 Durso.

7 Joe Gergen, “Airport Metal Detectors in On-Deck Circles?”The Sporting News, August 24, 1987.

8 John Eisenberg, “McDowell, Myers to Give Dull O’s Fire Next Year,” Baltimore Sun, December 20, 1995.

9 Stan Isle, “Mr. Efficiency Uses a First-Pitch Plan,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1988.

10 Paul Hagen, “The Best and Worst of Phillies (So Far),” Baltimore Sun, July 12, 1991.

11 Gary Carter and John Hough Jr., A Dream Season (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987).

12 Jack Lang, “Mets Closer With Closer,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1986.

13 “NL East Beat,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1989.

14 “Braves Name McDowell Pitching Coach,” Yahoo Sports, October 29, 2005.

Full Name

Roger Alan McDowell

Born

December 21, 1960 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.