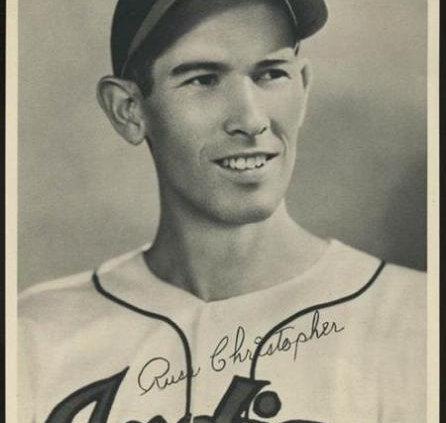

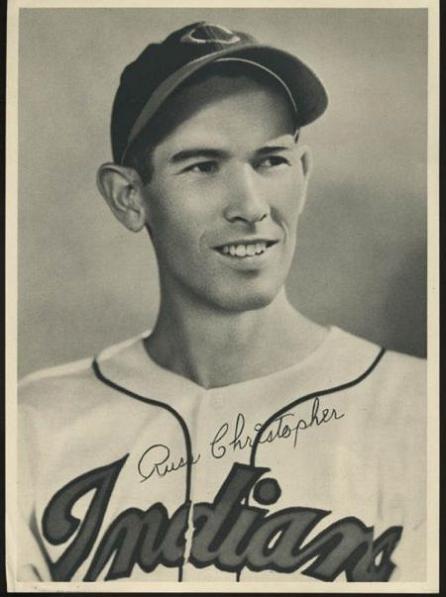

Russ Christopher

At six years of age, Russ Christopher was diagnosed with rheumatic fever. As a result, his heart became damaged. There was a small leak in one of his heart valves through which blood seeped, not allowing full circulation to his lungs. As a result, He was always out of breath. At times, when he overexerted himself, his face would turn a shade of blue. His teammates feared for his well-being. “Sometimes you didn’t know if he was going to make it,” said Cleveland Indians teammate Bob Lemon. “His lips were ashen. When he warmed up in the bullpen, he’d throw three pitches and say he was ready. He’d say, ‘I don’t want to leave it down here.’ His body could take only so much.”1

At six years of age, Russ Christopher was diagnosed with rheumatic fever. As a result, his heart became damaged. There was a small leak in one of his heart valves through which blood seeped, not allowing full circulation to his lungs. As a result, He was always out of breath. At times, when he overexerted himself, his face would turn a shade of blue. His teammates feared for his well-being. “Sometimes you didn’t know if he was going to make it,” said Cleveland Indians teammate Bob Lemon. “His lips were ashen. When he warmed up in the bullpen, he’d throw three pitches and say he was ready. He’d say, ‘I don’t want to leave it down here.’ His body could take only so much.”1

But despite Christopher’s physical weakness, in many ways he had the heart of a lion. The tall right-handed pitcher (6-foot-3½, 170 pounds) knew what his limits were between the white lines. Still, he took the ball when his manager called on him. He wanted to be a starting pitcher, but he switched to relief and learned to throw with a different motion — submarine — in order to prolong his career. A submarine pitcher, sometimes referred to as a sidewinder, releases the baseball at waist level or below. The effect is that the baseball will have a different spin as it approaches the batter. Often the ball will rise as it approaches home plate instead of dropping.

Baseball was the only way Christopher knew how to make a living. “The doctors know what’s wrong,” he said. “They say it doesn’t matter what I’m doing. I’m a pitcher. If I’m going to die, I might as well die pitching.”2

Russell Ormand Christopher was born on September 12, 1917, in Richmond, California, the third of four children born to Frank and Adele Christopher. Older sister Clara, older brother Frank, and younger brother Loyd made up the rest of the Christopher family. Frank Sr. owned an upholstery business.3

As a youngster, Russ had no interest in participating in baseball at Richmond High School. “The truth is that between the ages of 15 and 20, I didn’t care much about baseball,” he said. “I played some softball, but was much more interested in basketball. That was my number one sport, even though in high school I only made the “B” squad. But, my brother Loyd, two years younger than I, was full of baseball ambition, and was always looking up tryout camps.”4

Loyd was a star outfielder on the Richmond team. Shortly after he graduated, the New York Yankees held an open tryout near the Christopher home in Port Richmond. New York Yankees scouts Bobby Coltrin and Joe Devine liked what they saw of Loyd and offered him a contract.5 (Loyd played in a total of 16 games with the Red Sox, Cubs and White Sox in 1945 and 1947.)

Adele Christopher encouraged Russ to try his hand at baseball too. “Aw, I haven’t played in five years,” Russ said. “I couldn’t do anything.”6 But he relented, more to appease his mother than to play baseball. When Coltrin and Devine held another open tryout near Richmond. Russ tried out as an outfielder. He won a contract that earned him $75 per month and was sent to Class D El Paso of the Texas-Arizona League.

Russ joined Loyd on the El Paso roster in 1938. However, he batted only .163 in the early going and was given the job of batting practice pitcher.7 It was noted by his teammates how well he threw the ball. El Paso manager Zinn Beck watched Russ throw and he was not impressed. One of the pitches Russ threw got away from him and hit Beck. When Christopher said he hoped that he did not hurt the manager, Beck responded, “You ain’t got enough to hurt anybody.”8

As a result, Russ was sent to Class D Clovis of the West Texas-New Mexico League. When the lanky pitcher threw a curveball, he hurt his arm. Although the Pioneers’ trainers tried to bring him back around to playing condition, the arm did not respond. Christopher returned home after posting a 7-5 record with a 4.50 ERA. He found work at a fish oil plant and joined the Kenealey Independents, a semipro team, with the promise that he would not have to pitch. That promise was short-lived when the club ran out of pitchers and he was forced to the mound to help pick up the slack.

Although statistics are not available, Christopher’s pitches were said to be unhittable.9 The Yankees decided to give him another chance, sending him back to El Paso. Beck had been replaced as manager by Ted Mayer.

Despite a sore arm and his reluctance to throw curveballs, Christopher went 18-7 with a 3.68 ERA in 1939. That might have been the end of the Russell Christopher story. In the off-season, he was hunting with his brothers. They were using buckshot. After he needled Loyd about being a poor shot, Russ offered to prove his point. He moved about 30 feet away from Loyd and bent over a rock. Loyd, forgetting that he had replaced the buckshot with pellets, fired away. The shot found its way into Russ’s leg and drew blood. If the shot had been six inches higher, it might have killed him.10

In 1940 Christopher was assigned to Wenatchee of the Class B Western International League, where he got off to a 5-1 start. However, he battled another sore arm after he tried to throw a curveball,11 and ended the season 8-8 with a 4.72 ERA. Promoted to Newark of the AA Eastern League in 1941, he fed opposing hitters a steady diet of fastballs on his way to a 16-7 record with a 2.92 ERA for the 100-54 Bears. Despite the excellent record, Christopher had his detractors. “He’s a good seven-inning pitcher, but he’s not strong enough for the majors,” said Newark manager Johnny Neun.12

The Yankees left Christopher exposed in the Rule 5 Draft. He was claimed with the first pick by the Philadelphia Athletics on September 30, 1941. Christopher was considered the top prize in the pool of eligible players.13

As a result of the US entry into World War II, major and minor league players were being called up to active duty. Rosters were stocked with many older players who were able to extend their careers, when normally they might have been retired. Minor league players who otherwise would never make it to the major leagues were now populating the dugouts in big-league parks. Because of Christopher’s illness, his draft status was “4-F” — unable to serve in the military due to medical or mental reasons. Later Russ told Loyd, “You know, I was never really a major leaguer, but neither were three-fourths of those other guys.”14

The Athletics had fallen on lean times since winning three consecutive American League pennants (1929-1931) as well as back-to-back world championships (1929-1930). From 1935 to 1941, Philadelphia tussled with either St. Louis or Washington to avoid the cellar of the AL standings. The early war years did not change that status for the Athletics.

Philadelphia manager Connie Mack gave Christopher his first start on May 5, 1942, against Detroit at Shibe Park. He hurled a complete-game, three-hit victory, striking out six, a season high, in the A’s 2-1 win, He followed his successful debut with a 6-5 complete game win against Boston on May 10. “If two other pitchers come through for me as [Phil] Marchildon and Christopher have, we will be tough to beat,” said Mack. “Pitching is 90 percent of a club’s effectiveness.”15 But those back-to-back wins were the highlights of the season for Christopher. He ended the season with a 4-13 record and an ERA of 3.82. His lack of control was also a concern, as he issued 99 bases on balls while striking out 58 hitters.

Christopher again came up with a sore arm in 1943, this time missing almost two months of the season. He went 5-8 with a 3.45 ERA. On October 24 he married the former Virginia Lee Thompson of Easton, Pennsylvania. Two months later, the couple moved into an apartment house in Philadelphia. But a fire destroyed the building, causing several fatalities. Russ and Virginia lost all they had except the clothes on their back.16

Earle Brucker, the Athletics’ battery coach, went to work on Christopher. He changed him from an overhand motion to a sidearm delivery. Brucker also worked on teaching him how to throw an effective sinker. He was able to throw fromdifferent release points, making it difficult for the batter to pick up the pitches. Christopher also went to a no-windup delivery to preserve some energy.17 The results did not show right away, as he started with a 1-6 record in 1944. Philadelphia’s lack of offense contributed to Christopher’s losing record; they scored a total of two runs in five of his starts.

But Brucker continued to work with him, and Christopher looked like a new pitcher.An outstanding month of August (5-1, 2.05 ERA) contributed to his fine second half, allowing him to even his record at 14-14 with a 2.97 ERA for the season. He improved his control as well, striking out 84 hitters while walking 63. “I had a pretty good season in 1944, and would up with 14 victories against as many defeats,” said Christopher. “I was able to show them something out there on the mound.”18

Christopher got off to a hot start in 1945, winning his first three starts. After he beat the Yankees, 4-2, on June 17 at Shibe Park, his record was 11-2 with an ERA of 1.95. “If I didn’t have that fellow Christopher, I really would be up against it, “said Mack. “Every time he pitches, we know we have a chance to win.”19 But the rest of the 1945 season proved to be a disaster. He posted a 2-10 record from July through September. One of those games was a 24-inning marathon with the Tigers on July 21 at Shibe Park. Christopher, bum heart notwithstanding, started and hurled 13 innings, giving up one run and striking out eight. Forty-year-old Joe Berry pitched the final 11 frames. Detroit’s Les Mueller started and pitched 19 2/3 innings. The contest, which ended in a 1-1 tie after 4:48 of play, was finally called when home plate umpire Bill Summers reported he couldn’t see the ball anymore.

Christopher’s record for the season was 13-13 with a 3.17 ERA. He totaled 100 strikeouts, the only time in his career he reached the century mark. Mack rewarded him with a $2,000 bonus and a $10,000 salary for 1946.20 However, his heart condition had worsened. Christopher pitched only one complete game in 1946 compared to 17 in 1945. He also pitched 108 fewer innings in 1946.

Mack and Brucker agreed that Russ would be better served coming out of the bullpen. “Christopher is capable of a great deal of work, if given in small doses,” said Mack. “Every day, maybe.”21 In 44 games in 1947, all in relief, he had a 10-7 record with a 2.92 ERA and 12 saves. For the first time since Christopher joined the A’s, the club finished the season above .500 (78-76) and found themselves in fifth place in the AL standings. Mack had assembled a quality starting staff. In 1947, three starters had solid seasons: Marchildon, Dick Fowler, and Bill McCahan. The offense in 1947 was where the A’s had some holes.

Christopher was unhappy with his contract in 1948. The amount was the same as the previous year, $10,000.22 Starters made more money than relievers, and he believed that he could be a starting pitcher But in March he was diagnosed with pneumonia. He was hospitalized in Orlando; given his fragile condition, the outlook was that he might not pitch at all.

Cleveland owner Bill Veeck asked Mack if Phil Marchildon was for sale. Mack said no. Veeck then inquired about Christopher, but Mack declined, saying, “I can’t sell him, he has a bad heart.”23 Veeck offered Mack $25,000 and asked for Mack’s permission to talk with Christopher.24 Mack agreed. Veeck visited Christopher and the Indians’ boss convinced him to join the Indians. On April 3, Veeck handed $25,000 over to Mack (which was the same price that Mack had originally paid for Christopher in 1941). Veeck also gave Christopher a raise in salary to $12,500.25

When he was asked why he sold Christopher, Mack responded, “There were a number of reasons. First, I had a long talk with Christopher, and offered him more money if he would relieve. He refused, and gave me the impression he didn’t want to play with our club. It was just an impression. Maybe he wanted to play with the A’s as a starting pitcher — but a number of my players as well as the coaches felt he shouldn’t be a starter. I told all this to Mr. Veeck and explained that Christopher did not expect to pitch next year. But he asked my permission to talk to Christopher, and I granted it. My impression was that Christopher would refuse to leave us. But before talking to him, Veeck asked me to put a price on Christopher, and I did.”26

“I’m very happy to be with the Cleveland club,” said Christopher, “but, gee, I feel as though I’m coming here with two strikes on me. Both Veeck and Lou] Boudreau are counting on me so much, I hope I can make good. I’ll sure be trying.

“It wasn’t that I dislike being a relief pitcher. It was just I wasn’t getting anywhere with the Athletics as a relief pitcher. They would say, ‘Nice going’ but that was all the compensation I would get. You can’t buy bread with that.”27

In his memoir Veeck — as in Wreck, Bill Veeck told his version of the Christopher acquisition story. Veeck said, “I’ll take a gamble on you,” to which Christopher replied, “Bill, I think you’re crazy.” But the gamble paid off. Veeck noted, “Russ was a tremendous asset. . .In one spell at midseason, he practically kept us in the race.”28

Manager Boudreau used Christopher judiciously, often for an inning or less. But he made the maximum of his appearances. On August 6 against New York, he relieved Bob Feller in the ninth inning with the bases loaded. With one pitch, Christopher got George Stirnweiss to foul out to end the game. In 45 games, Christopher had a 3-2 record and an ERA of 2.90. As calculated retroactively, he led the league in saves with 17. Bill Veeck described how effective Christopher was with his “swooping, almost underhanded motion. Christopher’s ball would come from down under and then dip as it neared the plate, which meant that the hitters almost had to beat it into the ground. And that is precisely what a relief pitcher wants to make them do.”29

The Indians and the Boston Red Sox ended up tied atop the AL with identical records of 96-58. Cleveland beat Boston, 8-3, in the one-game playoff at Fenway Park. The Indians went on to dispose of the Boston Braves in six games in the World Series. Christopher made one appearance in the series. He faced two batters in Game Five, gave up one run on two hits, and did not record an out as the Braves were victorious, 11-5.

Christopher had told Veeck before the Indians purchased him that the 1948 season would be his last. Although Veeck tried to get him to return in 1949, Christopher was not healthy enough to do so. He retired from baseball with a career record of 54-64 and a 3.37 ERA. In 97 career starts, Christopher completed 46 games. He totaled 424 strikeouts and 399 walks. But perhaps his most noteworthy stat was a function of his submarine sinker: just one home run allowed every 26 1/3 innings.

In 1950 Christopher had open-heart surgery, and his prognosis was good. He moved his family to San Diego, where he worked in an aircraft plant.30 Bill Veeck wrote, “We helped him from time to time, wherever we could. No one ever had a stronger claim on our help than Russ Christopher, a thin, jug-eared, and gallant man. A pitcher.”31

Russell Christopher died on December 5, 1954, at Brookside Hospital in his hometown of Richmond. His death was the result of heart failure. He is interred at Sunset Mausoleum in El Cerrito, California. Christopher was survived by his wife Virginia, daughters Ethel and Lynn and son Ben.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Notes

1 Bob Dolgan, “’Thin Man’ to the rescue,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 16, 1998: 10-C.

2 Dolgan, “’Thin Man’ to the rescue,”

3 1930 United States Census

4 Frederick G. Lieb, “Mother Urged Christopher to Play Ball; Now He’s on Way to Hill Stardom for A’s,” The Sporting News, March 1, 1945: 9.

5 Art Morrow, “Willowy Mack On Way to Top As Relief Ace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 1947: 32.

6 Morrow, “Willowy Mack On Way to Top As Relief Ace,”

7 J.G.T. Spink, “Looping the Loop: The Thin Man at Home,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1945: 2.

8 Spink, “Looping the Loop: The thin Man at Home,”

9 Morrow, “Willowy Mack On Way to Top As Relief Ace,”

10 Spink, “Looping the Loop: The Thin Man at Home,”

11 Spink, “Looping the Loop: The Thin Man at Home,”

12 Spink, “Looping the Loop: The Thin Man at Home,”

13 “A’s Draft Star Pitcher”, Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1941: 32.

14 Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 308.

15 “Mack Sees Better Hurling For A’s,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 7, 1942: 29.

16 Red Smith, “Shadow A-Casting: The Story of Russ Christopher,” Baseball Digest, August 1945: 9.

17 Macht, 308.

18 Lieb, “Mother Urged Christopher to Play Ball; Now He’s on Way to Hill Stardom for A’s,”

19 “Player of the Week,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1945: 13.

20 Macht, 320.

21 Art Morrow, “A’s Keep Foes From Plate-Stay Away Themselves,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1947: 18.

22 Macht, 399.

23 Macht, 400.

24 Macht, 400.

25 Macht, 400.

26 Art Morrow, “Connie Mack Believes A’s Have Chance for Flag, If –,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 4, 1948: 45.

27 Harry Jones. “Christopher to Retire in October; Giants Top Tribe, 8-4,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 9, 1948: 22.

28 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck — as in Wreck. Many editions of this memoir, originally published in 1962, have been issued over the years. The one used in this biography is the 2012 edition from The University of Chicago Press (page 147).

29 Veeck, 146.

30 Frank Gibbons, “Christopher Perks up Brissie,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1952: 2.

31 Veeck, 148.

Full Name

Russell Ormand Christopher

Born

September 12, 1917 at Richmond, CA (USA)

Died

December 5, 1954 at Richmond, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.