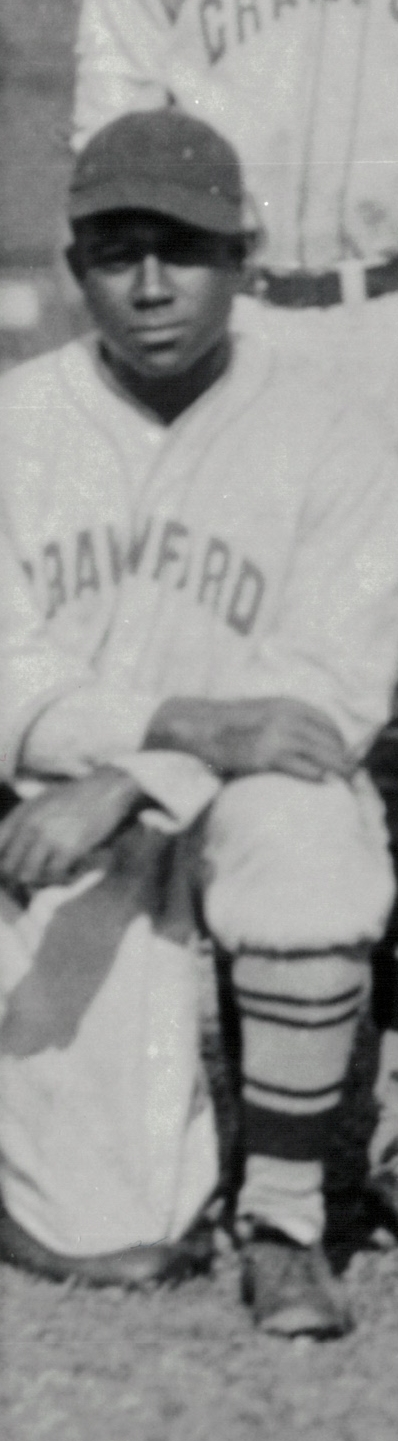

Sam Streeter

In 1981 the Smithsonian Institution hosted an exhibition called “Black Baseball: Life in the Negro Leagues.” A fair-sized crowd attended the exhibit when it opened on April 24 and Negro League stalwarts Buck O’Neil, Monte Irvin, Buck Leonard, and Judy Johnson were also on hand.

In 1981 the Smithsonian Institution hosted an exhibition called “Black Baseball: Life in the Negro Leagues.” A fair-sized crowd attended the exhibit when it opened on April 24 and Negro League stalwarts Buck O’Neil, Monte Irvin, Buck Leonard, and Judy Johnson were also on hand.

According to the Washington Post’s report about the exhibit’s grand opening:

“At one of the Smithsonian display cases yesterday, a 10-year-old named Richie Stark looked puzzled at a baseball autographed in 1930 by Sam Streeter, a terrific left-hander for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, known as the best black baseball team money could buy. ‘Who the heck was Sam Streeter?’ he asked.”1

Well, to be perfectly honest, Sam “Lefty” Streeter was not pitching for Crawfords in 1930, and Gus Greenlee did not start buying up players for the Crawfords until 1931. By the time he joined the Crawfords in 1931, Streeter, one of Greenlee’s first acquisitions, was a 30-year-old veteran who had achieved fame with that other Pittsburgh dynasty, the Homestead Grays of Cumberland Posey.

He was a heck of a player. As Streeter himself recalled in 1971, “I think I pitched two or three no-hitters. I don’t remember. They didn’t keep records in those days. We just wanted to play. If they said, ‘Sam, you pitch today,’ I pitched. Never worried if I had enough rest.”2

Sam Streeter was born in New Market, Alabama, about 120 miles north of Birmingham, on September 17, 1900, to Horace G. and Lula (McGuffey) Streeter. He had limited schooling and, per 1940 census data, received formal education only through the fourth grade. What his parents did to earn a living and more information in regard to his upbringing remain elusive.

The first notice of the 5-foot-7, 180-pound left-hander was in 1919 when he was pitching for Birmingham Industrial League teams. On June 23 he was hurling for Birmingham’s Edgewater Cubs and defeated Montgomery, 12-2.3 On July 1, pitching for the TCI Giants (also known as Ensley), he scattered five hits and hurled his first shutout as the team defeated Westfield, 5-0.4 On July 9 he hurled his second shutout, defeating Chattanooga, 3-0.5 He was on the mound for the first game of a doubleheader on September 8, nine days shy of his 19th birthday. He allowed four first-inning runs as his Ensley Steel Works Black Baron team lost to the ACIPCO Yellow Jackets, 6-2.6

In 1920 Streeter pitched for the Montgomery Gray Sox. His best performance of the early season was on June 7. The game at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field went 17 innings, and he pitched a complete game, losing 3-2 on fielding lapses that led to Birmingham’s run in the final inning.7 Montgomery was in the Negro Southern League and in late June had a 24-11 record, second only to Knoxville. On July 22, in a nonleague game against the Chicago Black Sox, Montgomery won easily, 15-1. Streeter allowed only four hits and threw 20 consecutive strikes at one point.8 On August 14 he spun a one-hitter as Montgomery defeated Birmingham 1-0.9 The Gray Sox won the league pennant, but Streeter would play elsewhere the following season.

In 1921 the trail of Streeter’s career is unclear. The then common practice of not including a player’s first name in stories only confuses matters, as does the not-uncommon practice of players jumping from one team to another. One report had Streeter signed by Frank Perdue to play for the Birmingham Black Barons.10 He didn’t play for Birmingham. Another report has Streeter pitching for Mobile in a 7-5 loss to Birmingham on May 6, but there is no other mention of his being with Mobile. Streeter started the season with the Atlanta Black Crackers and was with the team through July 8. He signed with the Chicago American Giants of the Negro National League, and he first appeared with them on July 17, 1921, winning 11-2 against a team called the Magnets.11 He spent the balance of the season with the American Giants.

In 1922 Streeter was on the move again, this time with the barnstorming Atlantic City Bacharach Giants team led by Dick Lundy. Statistics for the season are not readily available, but it is known that on July 30 he pitched in both games of a doubleheader at home against the J&J Dobson team from Philadelphia. In the opener he scattered seven hits in a complete-game 4-3 win. In the nightcap, he relieved Joseph Wheeler in the ninth and saved a 3-2 win.12

On September 27, 1922, Streeter married Euzell Huguly, who had been born on July 9, 1902, in Georgia. It is not known how long they were together or if they had any children. Sometime after 1930, Streeter married again. He and his second wife, Myrtle, who was born on March 21, 1910, had a daughter named Mary Lou, who was 7 years old at the time of the 1940 census.

In 1923 Streeter joined the New York Lincoln Giants, a member of the Eastern Colored League that nevertheless played most of its games against nonleague opponents. On June 3 the bus stopped in Plainfield, New Jersey, and the opposition was provided by a team known as Recreation. Streeter started the game and was not scored upon in the first six innings. He weakened in the late innings as Recreation came back to tie the game, 6-6, in the ninth. In that inning Streeter surrendered a game-tying two-run homer to Hap Myers, who had played in the majors for parts of five seasons. After the homer, the frustrated Streeter removed himself from the mound and switched positions with right fielder Dave Brown. Brown stopped the bleeding, and the Giants won the game in the 11th inning when Robert Hudspeth tripled and came home on a single by Orville Singer.13 On August 19, in one of his best performances of the season, Streeter shut out Brooklyn’s Royal Giants, 5-0, allowing only three hits.14

In 1924 Streeter was with the Birmingham Black Barons and pitched for them through the early part of 1925. He was 14-6 in league play in 1924, when the team went 34-44, and he was 0-1 in early 1925. On May 25, 1925, he was signed by the Homestead Grays.15 That day he defeated Braun’s Knickerbockers, 12-4.16 The Grays won 27 of their first 30 games with two losses and one tie, and Streeter contributed two wins to that total.17

By the time the bus stopped at Coshocton, Ohio, on June 18, the team was 42-3 and Streeter, who had a potent bat, was slated to play center field.18 His second shutout of the season came on July 18 at Forbes Field against Bellevue. He scattered five hits and only one runner made it as far as second base.19

Lefty Streeter was not known for his blazing speed. He featured a curveball and at times could put a little extra on the ball. That little extra came courtesy of substances not necessarily allowed in baseball. On July 25, 1925, in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, he entered the game in relief of Smokey Joe Williams. A new ball had been put in play and Streeter, per his custom, had prepared the ball by rubbing it on the ground. The umpire took exception to this practice and threw Streeter out of the game. Shortstop Gerard Williams protested by throwing a new ball into the stands and was likewise asked to leave the premises. Jeannette won the game, 3-2.20

Jeannette was accused of using a ringer in the form of pitcher Louis “Red” Temple, who had gone to spring training with the Boston Red Sox in 1925 but had never pitched for them once the regular season had begun. In 1927 and 1928, Temple pitched with Jeannette in the Class-C Middle Atlantic League, going 18-10 in 1928. Grays player-manager Vic Harris protested so vigorously that he was ejected as well as Streeter and Gerard Williams. This gained the ire of William G. Nunn in the Pittsburgh Courier who called the game “a combination of football, volley ball, boxing (and) wrestling,” and scolded the team for jeopardizing the outcome by losing three players via ejection.21

At Forbes Field on October 3, Streeter wrapped up his season with a 16-1 win over Homewood in the first game of a doubleheader. He allowed only five hits, struck out eight, and had four of his team’s 20 hits.22 According to the Pittsburgh Courier, the team won 125 of the 150 games it played in 1925, and wins on September 24 at Finleyville and October 3 at Forbes Field brought Streeter’s record to 23-5, an incredible feat since he had not joined the team until May and missed almost two weeks when he suffered a spike wound on August 25.23

Streeter was with the Grays through the end of the 1926 season. His teammate Oscar Owens reminisced in 1938, “That … club had everything. Power … speed … and brains. That was the year we won 43 straight games, which I believe is some kind of record. We beat almost everything we came up against. They didn’t come too big or too strong. All we wanted was a game with them and we never worried much about the outcome.”24

The 1926 Grays were indeed a powerhouse. In a relief effort on May 15 against Bellevue (Pennsylvania), Streeter entered the game in the third inning with his team trailing by three runs. He pitched nine innings, allowing only three hits, as the Grays came back to tie the game. Darkness caused a halt to the proceedings with the game tied 3-3 after 11 innings.25

The team simply refused to lose. The Grays were undefeated in their first 47 games (43-0-4). On June 10 the streak was broken at Coshocton as Streeter suffered his first loss.26 Through 64 games, the Grays were 57-3 with four ties.

On July 25 Homestead traveled to Cleveland to take on the Cleveland Elites of the Negro National League. With Streeter striking out eight, the Grays won 15-3.27 According to the Pittsburgh Courier, the team’s record by late August was 102-6 with six ties. At a dinner in August, team owner Cum Posey presented the players engraved gold baseballs in honor of their achievement.28

The Grays played relatively few games at their home ballpark in Homestead, Pennsylvania, outside Pittsburgh. They seemed to spend more time on the bus than at the ballpark. On August 28 the bus made a stop at Russell Field in Warren, Pennsylvania, where Streeter pitched a 7-0 shutout, scattering seven hits, to push his record to 24-3 as the Grays defeated the Warren Wreckers.29 The team ended the season with 147 wins.

After the season the Grays were matched up against an American League all-star team. Streeter made a brief appearance in the game on October 3 when he took the mound in top of the 10th inning (replacing George Britt, who had been ejected) with the score tied and the bases loaded. Streeter, without ample opportunity to warm up, was ineffective and the American Leaguers wound up scoring five runs to win the game, 11-6. (Lefty Grove finished the game for the All-Stars and retired the Grays in the bottom of the 10th.)30

Although he had experienced great personal and team success with the Grays, Streeter returned to Birmingham in 1927. On May 3 he entered the game against the Cleveland Hornets with two out in the fifth inning after starter J. Burdine and reliever Fred Daniels allowed a pair of runs and left the bases loaded. After allowing a base-clearing triple to Orville Riggins that tied the game, Streeter retired the next 13 batters in order. The Barons came back to win the game, 7-5.31 Three days later he shut out the Hornets on three hits, 4-0. The team’s record at that point was 8-2, and they led the Negro National League. Among his teammates was a young Satchel Paige, who had started the season with Chattanooga. When the Black Barons completed a five-game series at St. Louis on June 29, Paige and Streeter combined to defeat the St. Louis Stars, 11-4.32 Birmingham won the second-half championship with a 29-15 record but was swept in four games by the Chicago American Giants, winners of the first-half pennant, in the league championship. Available records indicate that Streeter was 14-12 and batted .381 in 1927.

Streeter and fellow pitcher Harry Salmon took the young Satchel under their collective wings. Years later, Streeter remembered, “See, he’d wind up and wouldn’t watch his batter. He’d look around and when he’d come back, he didn’t see where he was throwing it. I told him to kind of keep his eye on the plate, not to turn too far, to glance at the plate before he turned the ball loose. He got to the point where he had good control.”33

In 1928 Streeter was back with the Grays, and he got off to a good start with two early wins, the first of which came at home in an 11-1 win over the Eastern Ohio League All-Stars on May 12.34 The Grays got off to another sensational start and won 26 of their first 27 games. They had an 18-game winning streak going when Streeter experienced misfortune as he had two years earlier. This time, he made an error at a key point and the Grays lost to New Castle to put an end to their winning streak.35

On Memorial Day, May 30, the Grays played three games. The morning was spent in Canton, Ohio, where they defeated the Canton Raven Oils. Streeter was given the ball in the second game and defeated Canton, 8-3. That evening, at Forbes Field, the Grays defeated Homewood and improved their record for the year to 37-3.36 Streeter’s record for the season was 6-1 at that point.

Streeter remained with the Grays in 1929, and the team became part of the six-team American Negro League, though the team still continued to barnstorm. In league competition, things were not easy as the Grays got off to only a 6-6 start and were in third place. They moved into contention in mid-June when they took four games in a row from Baltimore. Streeter posted a 5-2 win on June 13 and a 6-5 win in the second game on June 15. After defeating Hilldale in a doubleheader on June 23, the team was poised for a battle for the first-half championship, but fate stepped in the way. On June 25, the team was headed east when one of the team cars, driven by owner-manager Posey, went off the road. Pitcher Oscar Owens, second baseman Walter Cannady, and outfielder E.W. Graham were seriously injured.37 The Grays pressed on. Streeter won a 6-3 game against Hilldale on June 29 in which he scattered nine hits and got support from Johnny Beckwith, who had three hits. With four games remaining in the first half, the Grays were 1½ games behind Baltimore and needed to win three of four games at Baltimore on June 30 and July 1 to capture the first-half championship. Baltimore swept the four games and the Grays slipped to third place. In the second half of the season, the Grays finished in fourth place with a 19-16 record.

The American Negro League only lasted for one season, and in 1930 Streeter was back with the Black Barons, who were in the Negro National League. Twice in August he defeated the Chicago American Giants at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. On August 5 he hurled a five-hitter in a 2-1 win.38 On August 14 at Birmingham, the Black Barons swept a doubleheader from Chicago with Streeter winning the first game, 9-8. Birmingham concluded its season on Labor Day with a doubleheader sweep of the Nashville Elites. In the opener, Streeter won 4-2, pitching his way out of three jams, the last one in the eighth inning. In the second game, Satchel Paige pitched a 4-0 shutout.39 The team finished the season at 46-48-2, the fifth best record in the league.40

In 1931 Streeter began the season with Cleveland and was among the first players signed by Gus Greenlee to play for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, joining the team on June 3.41 A matchup with Streeter’s former team, the Grays, took place on June 19 at Forbes Field and the Grays won, 9-0.42 During the season, Greenlee openly raided other teams for talent, signing Grays outfielder Ambrose Reid and luring Satchel Paige away from Cleveland. The team barnstormed throughout the 1931 and 1932 seasons. One of the stops in 1932 was Dexter Park in Queens, New York, the home of the semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks. Streeter pitched the first game of a doubleheader against the Bushwicks, scattering four hits and winning 10-0.43

In 1933 the Crawfords joined the Negro National League and finished the first half in second place with a 20-8 record. Streeter’s best performance of the season came at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field when he hurled a two-hit masterpiece as the Crawfords defeated the Nashville Elites, 1-0, on July 17.44 Streeter was selected to play in the first-ever East-West Game at Comiskey Park, an all-star event that featured the best players in Negro baseball. He was the starting pitcher for the East and pitched into the sixth inning. He allowed a homer to former Birmingham teammate Mule Suttles in the fourth inning but still took a 5-4 lead into the sixth inning; however, a leadoff single by Willie Wells and a one-out double by Alex Radcliffe tied the score.45 At that juncture Streeter left the game with the lead run on second base and Suttles due up at the plate. His mound replacement, Crawford teammate Bertrum Hunter, yielded a double to Suttles that put the West in front to stay as they won the game, 11-7. The Crawfords took the second-half NNL championship in a playoff with Nashville, but there was no postseason series between first-half champion Indianapolis and the Crawfords.

In 1934 Streeter returned to the Crawfords, and showed that he still could do the job in a whitewashing of the Philadelphia Stars on June 11. In a game at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, all he needed was a solo homer by Vic Harris. The Crawfords won, 1-0, as Streeter scattered six hits.46 Although the Crawfords had the best overall record, the league played a split season with Chicago winning the first half and the Philadelphia Stars the second half. The Stars won the championship in eight games. (There was one tie.)47 The Crawfords’ chance for the championship would come the next season.

In 1935 Streeter was part of the Crawfords team that won the first-half championship with a 26-6 record. On Memorial Day he pitched the first game of a doubleheader as the Crawfords defeated the Stars in Philadelphia, 11-4. The Crawfords swept the doubleheader and went on to sweep the next four games from Newark to separate themselves from the pack. Streeter was given the ball on July 4 and defeated the Homestead Grays in the first game of a doubleheader, 6-2. He scattered six hits and was given offensive support by Cool Papa Bell, who smashed a three-run homer.48

The Crawfords did their usual amount of barnstorming and on June 13, they were at Chester, Pennsylvania. Arriving late and missing a couple of stars due to a miscommunication, the team took the field with Streeter filling in at first base. In the third inning, Streeter hit a grand slam. That was all pitcher Rosey Davis needed as the Crawfords won 6-1.49

On August 21 Streeter defeated the Madison Blues in Madison, Wisconsin, 5-2. The Blues were kept off guard by Streeter’s spitball, and the Crawfords pulled off a triple play in the first inning. The game was a vintage Crawfords effort. Cool Papa Bell led off the game with a double, stole third base, and came home on a single by Pat Patterson. Patterson then stole second and scored on a triple by Bill Perkins. An inning later, Bell’s second double scored Chet Williams, and Sam Bankhead drove in Bell. The Crawfords’ scoring was completed when Josh Gibson tripled in the third inning and scored on a groundout. Streeter scattered nine hits.50

Streeter opened the Negro National League Championship Series at New York’s Dyckman Oval against the New York Cubans on September 13 and lost, 6-2, as the Cubans came from behind on two homers by Rap Dixon.51 It was his only appearance in the Series. The Crawfords’ first win in the Series was a 3-0 gem by Leroy Matlock at Dyckman Oval in Game Three. Down three games to one, the Crawfords came back to win the next three games, each by one run, to take the Series.

Streeter’s last season with the Crawfords was the 1936 campaign. On May 10 they swept the Cubans in a doubleheader. In the opener Paige, with the help of homers by Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston, won 8-4. Streeter pitched the second game and came away with a 6-5 win in which Gibson clouted two more homers. The Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “[L]ike the first, it was such a spectacular ballgame that almost every fan remained until the last strike was called on the last batter. Then they went home, as contented as the cows that give Carnation milk.”52

In August things got a little muddled in the Negro National League. Streeter was named to a Negro League all-star team that won the annual Denver Post tournament on August 11. On the way back from Denver, the All-Stars faced the House of David in Des Moines, Iowa, on August 14. Satchel Paige started for the Negro All-Stars and left the game after homering in the second inning. Streeter took over and pitched the remainder of the game as his team won 19-0. Streeter struck out nine and allowed five hits to a version of the House of David team that was one of several teams using that name and bore little resemblance to the original House of David team.53 While Streeter and the other Negro National League players were on a two-week barnstorming jaunt, the remaining players continued to play league games.

The Crawfords won the second-half NNL championship with a 20-9 record and played the Washington Elites for the league championship – or did they? In the confusing world of Negro League Baseball, Washington (also known as the Nashville Elite Giants) did not win the first-half championship until September 17, when they played a makeup game. What counted and what didn’t in the postseason is not readily apparent. On September 21 Streeter started for the Crawfords in Game One of the playoff series and lost, 2-0. Doubles by Biz Mackey and Jim West accounted for Washington’s runs.54 There was no Game Two.

The appetite for a championship was still there and a best-of-three series was scheduled in Nashville, beginning with a doubleheader on September 27 and concluding with a single game, if necessary, the next day. The Crawfords won the first game, 9-8, and the Elites won the second, 2-1, to set up the Monday-night showdown. There is no record of that game ever having been played. In any case, Streeter had appeared in his last game as a professional player in the Negro Leagues.

Streeter pitched in Pittsburgh’s South Hills League, a sandlot organization, in 1937, and on August 8, 1938, he was there when the Homestead Grays commemorated their 25th anniversary. After baseball, Streeter stayed in Pittsburgh and worked as a laborer at the Jones & Laughlin steel mill until he reached retirement age.55 He died in Pittsburgh on August 15, 1985, at the age of 84, and was buried at Homewood Cemetery in Pittsburgh.56

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Seamheads.com, Ancestry.com, and the following:

“Black Barons and Gray Sox to Play – Leading Negro Clubs to Furnish Labor Day Doubleheader.” Birmingham News, September 5, 1920: Sports, 1.

Carter, Ulish. “Streeter Was a Class Pitcher and Man in the Negro Leagues,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 23, 1974: 26.

Clark, Dick, and Larry Lester. The Negro Leagues Book, (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994).

Cowans, Russell J. “West Defeats East in Diamond Classic: Big Bats of West Hammer Three Eastern Pitchers Hard.” Detroit Tribune, September 16, 1933: 7.

Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001).

Nunn, William D. “Modern Baseball’s ‘Miracle Team,’” Baltimore Afro-American, November 3, 1928: 12.

“Oscar Owens, Homestead Pitcher, Is in Class by Himself When It Comes to Hurling No-Hit Contests,” Warren (Pennsylvania) Tribune, August 26, 1926: 7

Smith, Wendell. “Smitty’s Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 13, 1938: 16.

Notes

1 Jean M. White, “Ballpark Figures: The Other League,” Washington Post, April 25, 1981: B1, B4.

2 Jerry Vondas, “Bucs Victory Stirs Memories for Former Grays Players,” Pittsburgh Press, October 7, 1971: 42.

3 “Edgewater at Montgomery, June 23,” Birmingham News, July 6, 1919: 23; “In the Baseball World: Edgewater at Montgomery, June 23,” Birmingham Reporter, July 5, 1919: 8.

4 “Ensley Defeats Westfield,” Birmingham News, July 6, 1919: 23; “Ensley TCI Giants Goose Egg Westfield, Holding Them to Five Scattered Hits,” Birmingham Reporter, July 5, 1919: 8.

5 “In the Base Ball World: Streeter’s Curves Puzzle the Chattanooga Giants,” Birmingham Reporter, July 12, 1919: 8.

6 Walter S. Brown, “Yellow Jackets Take Game from Black Barons by Winning Twin Bill at Rickwood Park,” Birmingham Reporter, September 13, 1919: 8; “Black Barons Are Given Double Loss,” Birmingham News, September 9, 1919: 7. ACIPCO stands for American Cast Iron and Pipe Company.

7 “Black Barons Win Seventeen Inning Battle,” Birmingham News, June 8, 1920: 8.

8 “Montgomery Sox Swamp Chicagoans,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 23, 1920: 5.

9 “Black Barons Meet Third Straight Loss,” Birmingham News, August 15, 1920: 4.

10 Zipp Newman, “Barons Tackle Alabama Squad in Tuscaloosa,” Birmingham News, March 30, 1921: 14.

11 “Amer. Giants, 11; Magnets, 2,” Chicago Tribune, July 18, 1921: 11.

12 “Bacharach Giants Win Both Games,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 31, 1922: 11.

13 “Lincoln Giants Go Eleven Innings to Beat Recreation 7-6,” Plainfield (New Jersey) Courier-News, June 4, 1923: 12.

14 “Lincolns and Royal Giants Divide Double Header Last Sunday at Protectory Oval,” New York Age, August 25, 1923: 6.

15 “Grays Sign Hurler,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, May 26, 1925: 12.

16 “Grays Down Knickers,” Pittsburgh Post, May 26, 1925: 14.

17 “Streeter a Winner in Debut Here,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 6, 1925: 12.

18 “Victorious Record Held by Visitors,” Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune, June 18, 1925: 9.

19 William J. Pfarr, “Bellevue Blanked by Grays,” Pittsburgh Sunday Post, July 19, 1925: 3-7.

20 “Homestead Grays Lose to Jeannette,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 26, 1925: 3-3.

21 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Dope: Getting the ‘Bum’s Rush’ to the Showers,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1925: 12.

22 “Homewood Loses Two to Grays,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, October 4, 1925: 3-4.

23 “Grays Twirling Staff, Turning 120 Victories Out of 144 Games, Takes Rank as ‘Greatest Four’ in Independent Circles, Pittsburgh Courier, September 26, 1925: 12.

24 Chester Washington Jr., “Sez Ches: Iron Man Back in Iron Town,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 30, 1938: 16.

25 “Grays, Tied by Two Teams, Out for Independent Mark.” Pittsburgh Courier, May 22, 1926: 14.

26 “Grays to Meet Coshocton Nine Saturday at Forbes Field,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1927: Section 2: 4.

27 “Cleveland Beaten by Homestead Grays, 15-3,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 31, 1926: 14.

28 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Dope,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 21, 1926: 14.

29 “Homestead Lives Up to Advance Notices and Thrills Hundreds of Warren Fans Saturday Afternoon,” Warren (Pennsylvania) Tribune, August 30, 1926: 6.

30 “Grays and American League Stars Split,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 9, 1926: 15; “Big Leaguers Conquer Grays in Ten Frames,” Pittsburgh Post, October 4, 1926: 11.

31 “Black Barons Beat Hornets in Second Tilt,” Birmingham News, May 4, 1927: 13.

32 “Black Barons Beat St. Louis Stars in Series Final, 11-4,” St. Louis Daily Globe Democrat, June 30, 1927: 10.

33 Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2009), 44.

34 “Grays Decisive in Local Debut,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 19, 1928: Section 2: 4.

35 “Grays Invade Ohio Thursday,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 26, 1928: Section 2: 4.

36 “Generals to Clash with Homesteads; Nonskids at Home,” Akron Beacon Journal, June 2, 1928: 23.

37 “Grays in Auto Wreck,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 29, 1929: 1.

38 “Black Barons Win Again,” Birmingham Reporter, August 9, 1930: 6.

39 “Black Barons Win Twin Bill from Elites,” Birmingham News, September 2, 1930: 13.

40 The season record is according to seamheads.com, accessed February 2020.

41 “Streeter Now with Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 6, 1931: Section 2: 4.

42 “W. Foster Silences Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 27, 1931: Section 2: 4.

43 T. Jay Murphy, “Pattison Blanks Crawfords with Three Hits in Sunset Tilt; Visitors Take First,” Long Island Daily Press (Queens, New York), September 26, 1932: 10.

44 William J. Moore, “Elites Win Series from Crawfords,” Birmingham Reporter, July 22, 1933: 3.

45 Chester L. Washington, “‘Mules’ Suttles Scorching Homer Blazed West’s ‘Victory-Trail’ in East-West Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 16, 1933: Sports-4.

46 “Streeter Blanks Stars,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 12, 1934: 17.

47 Sources vary as to what Pittsburgh’s overall record was in 1934, as well as who won the half-season titles. Seamheads.com says Philadelphia won the first half and Chicago won the second half, but several sources have it the other way around. According to contemporary sources and two books, Chicago won the first half and Philadelphia the second half. Books include John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History, 305, and Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds., The Negro Leagues Book, 161. Newspapers showing standings are Pittsburgh Press, July 11, 1934: 26, and Pittsburgh Courier, September 8, 1934: 14 (second half). The overall record varies as well. Lester shows the record at 29-17, Holway shows it at 64-22; and Seamheads.com has it as 47-27-3 (in the league). Each shows that the Crawfords had the best overall record.

48 “Craws Win Four, Lose Two in Gray Feud,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 13, 1935: 15.

49 “Pittsburgh Beats Chester; Cuban Stars Here This Evening,” Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, June 14, 1935: 17.

50 Henry J. McCormick, “Crawfords Complete Triple Play, Beat Blues 5-2,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), August 22, 1935: 11.

51 “Crawfords Lose to Cubans, 6-2,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 14, 1935: 16.

52 Chester L. Washington, “Ches’ Sez,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 16, 1936: Section 2, 5.

53 Sec Taylor, “Paige Stars in Contest Here,” Des Moines Register, August 15, 1936: 5, 7.

54 “Porter Pitches Three-Hit Ball to Give Elites 2-0 Victory over Craws in First game of Play-Off,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 26, 1936: Section 2, 4.

55 John Holway, “Black All-Stars Celebrate Anniversary, Too,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 5, 1983: 13.

56 Some sources indicate a death date six days earlier, on August 9, 1985.

Full Name

Samuel Streeter

Born

September 17, 1900 at New Market, AL (US)

Died

August 9, 1985 at Pittsburgh, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.