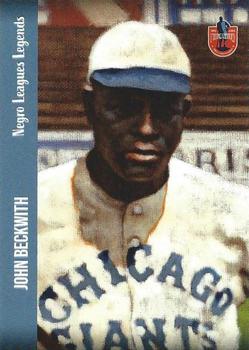

John Beckwith

John Beckwith was a tremendous slugger who has received more attention for home runs hit outside of regular season Negro League play than for his superlative production during Negro League games. However, he has yet to receive induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. This lack of recognition may reflect his frequent position and team switches, stemming from a perhaps undeserved reputation for poor glovework and people skills.

John Beckwith was a tremendous slugger who has received more attention for home runs hit outside of regular season Negro League play than for his superlative production during Negro League games. However, he has yet to receive induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. This lack of recognition may reflect his frequent position and team switches, stemming from a perhaps undeserved reputation for poor glovework and people skills.

Beckwith hailed from Louisville, Kentucky. The ballplayer’s great-grandfather, Abraham Simms, “was very prominent in Louisville’s Black community. He was Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Green Street Baptist Church … First known as Second African Church, this house of worship originated at 1st and Market streets on 9/29/1844. The church moved to Green Street in 1860 and changed its name.”1

A grandson of Simms, Jacob Beckwith, married Daisy Smith on January 13, 1898. They had four or five children; 1920 Census records show Daisy Beckwith having given birth to five children, but we have information on four: Stanley, born on July 11, 1896; Alice, born in March 1898; John, born on January 10, 1900; and Leroy, born in 1902.

Beckwith first received press attention in his early teen years when in 1913 the Chicago Defender listed him as a utility infielder on a youth team.2 That positional designation foreshadowed his professional career. After he was discovered on the sandlots by the great Rube Foster,3 Beckwith played his first year of pro ball in 1919 for Joe Green’s Chicago Giants. Available statistical data indicate that he had three hits in 17 at-bats. Before John joined the Giants, his older brother Stanley briefly played shortstop for them.

Beckwith continued with the Chicago Giants in 1920 following the formation of the Negro National League. These Giants were the worst of the three Giants team in the NNL that year, finishing last with a record of 5-31. But young Beckwith started to show that he could hit consistently. Primarily playing shortstop and catcher, he put up a slash line of .285/.324/.394 while playing in all of the team’s 36 league games.

Standing about six-foot tall and weighing 200 pounds, Beckwith would develop into a powerful right-handed hitter.4 He improved markedly in all hitting categories in 1921, slashing .371/.415/.559 in 47 games as the Chicago Giants again finished last in the NNL. Beckwith hit a monumental home run that season in a May 22 game that his team lost 14-2 to the Cincinnati Cuban Stars. Since major-league play began at Redland Field in 1912, no homers had been hit over the fence on a fly.

Leading off the second inning against Stars pitcher Claudio Manela, Beckwith pulled one deep to left. The ball sailed over the left-field fence by about 10 feet and touched down on the roof of a factory building on the other side of an alley behind the fence. The fans were so excited by the first over-the-fence home run in Redland Field history they rained coins down on Beckwith, who ended up with a take reported to be $25-$65. He almost added a second homer later in the game, but his opposite field shot fell just short.5

In 1922 Beckwith moved up from the Chicago Giants to the Chicago American Giants, winners of the first two NNL pennants. “Beckwith was a great natural ball player,” said Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss, who was second baseman and captain when “Beck” joined the team. “He had great hitting power, a strong throwing arm, and a fiery temper.”6 Beckwith played third base that season for the American Giants, and turned in an OPS of 1.004, the first of his four full seasons with an OPS of more than 1.000.

Switching his primary position to first base in 1923, Beckwith continued to wield a big bat. His 1923 teammate Bill Foster later said, “If you made just one mistake to a man like Beckwith – just one wrong pitch – the ballgame was over.”7 His OPS dipped to .887 in the last of his five Chicago seasons. Still, as one of the greatest sluggers in the game, he was recruited by the manager of the unaffiliated Homestead Grays, Cum Posey, and after months of dickering signed a contract. “His salary, it is said, will be the highest ever offered a player for jumping the big leagues for an independent team,” reported the Pittsburgh Courier.8

In the first of many interpersonal disputes that plagued his career, Beckwith did not last a season playing for Posey. “Beckwith was unable to fit into our organization, and we felt that we had to either let him go or ruin the morale of our club,” Posey declared. “There is no gainsaying the fact that he is one of the greatest ball players of all times, and he leaves the club with the sincere wishes of everyone that he make good with whatever team he may play.”9

Beckwith went to the Baltimore Black Sox of the Eastern Colored League. He scored 33 runs in 33 games, playing one position (shortstop) exclusively for the only time in his career. The official statistics today counting league games show Beckwith with seven homers. However, a story written after the 1924 season that presumably includes non-league games has Beckwith as the ECL leader with 42 dingers.10

An offseason story quoted Baltimore owner George Rossiter denying that Beckwith would supplant Pete Hill as Black Sox manager.11 Another report about a month later showed that Beckwith’s winter job involved a different kind of sports management: he owned a “popular pool room”12 in Chicago. The initial report notwithstanding, the rumor proved true as Baltimore named the 25-year-old Beckwith manager.

Fans of the 1925 Black Sox must have felt equal parts adoration and frustration toward their team, which had three of the biggest sluggers in baseball. Left fielder Heavy Johnson hit .327. First baseman Jud Wilson had a sensational slash line of .370/.421/.581. Yet player-manager Beckwith bested Wilson across the board with .404/.473/.738 marks, all career major-league highs, while playing mostly shortstop, but appearing at every infield position as well as catcher. In 50 league games, Beckwith had 15 homers, but a July 25 photo caption credits him with a league-leading 22.13 Two weeks later, a story about a Harrisburg game reported that Oscar Charleston had tied Beckwith with 24 homers.14

Despite this trio of powerful bats, the Black Sox had below-average hitters at every other spot in the lineup, which led to a middling 33-31-2 record in the Eastern Colored League, and a 36-33-2 record overall. Beckwith’s triumphs on the field did not extend to the dugout. After a league suspension for making contact with an umpire, the Sox replaced Beckwith with his predecessor.15 Beckwith went 25-18-1 as manager, a mark far superior to Hill’s 11-15-1.

Beckwith had a better record as manager in part because he kept himself in the lineup as a player but ditched the team rather than finish out the season under Hill. The Afro-American reported that “Beckwith left without notifying the club owners of his intention…. As a player he was one of the greatest but failed completely as a mentor. Dissension was … rampant among the rest of the team members, which was credited as the cause of several games being lost.”16

After a bittersweet season, Beckwith had a sad offseason. He left to play winter ball in Cuba,17 but had to return home days later following the death of his mother.18

Beckwith signed a contract to play for Homestead again in 1926, upsetting his most recent former team: “Beckwith is the property of the Black Sox and if Posey, manager of the Grays, has signed a league player, he has violated an agreement with [Eastern Colored League] owners,” said Charlie Spedden, business manager of Baltimore.19 Beckwith played just two games for Homestead before going back to Baltimore.20 He missed time with the Black Sox “due to several torn ligaments in his right arm.”21

Beckwith’s three-year stay with Baltimore ended when the Sox traded him to the Harrisburg Giants for two pitchers (Darltie Cooper – who would later join forces with Beckwith to great effect – and Wilbert Pritchard), a third baseman (Mark Eggleston), and possibly cash considerations.22 “Beckwith modestly admitted that Harrisburg got the best of the deal in the … trade.”23 The facts support Beckwith’s brag. Beckwith’s 1.0 WAR with Harrisburg doubled the combined total of the Baltimore trio (0.5). The extra one-half win over about one month of games translates into about three extra wins over the course of a six-month season.

Beckwith once again found himself the subject of trade rumors in early 1927, with a complicated plot involving two separate trades with the Chicago American Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs.24 Beckwith not only stayed with Harrisburg, but for the second time in three seasons took over managing a team from a future Hall of Fame outfielder when he replaced Charleston.25 Columnist W. Rollo Wilson opined, “This will not be Beck’s first essay at the role of boss, but I expect it will be far more successful than his last attempt. With added years and sense I look for the hardest hitting man in baseball to take the game seriously and to have his team up there all the way.”26

Beckwith liked his squad. “I don’t say positively the Harrisburg Giants will win the pennant, but I am reasonably sure,” said Beckwith. “The Giants … are stronger than they were last season at bat and at field…. I have three new bats this season and I expect to hang up a home-run record for colored baseball if Charleston don’t beat me out,” he continued.27

As it developed, Beckwith had a good but not great season both as a manager and a player. In 1926 Harrisburg had finished in fourth place with a 27-22 record under Charleston. In 1927 Beckwith guided the Giants to second place with a 38-31 mark. Beckwith hit nine homers in 67 games, good for runner-up on the team to Charleston’s 13. Darltie Cooper, one of the players traded to Baltimore for Beckwith in 1926, rejoined Harrisburg and posted a career-high and team-leading 5.1 WAR playing for Beckwith in 1927.

Also in 1927, Beckwith married Dorothy Hill. They did not have children.

Accounts published years later, including one in the groundbreaking Only the Ball Was White,28 assert that Beckwith hit 72 homers in 1927 and 54 in 1928. The latter season received more ink at the time than the former.

In 1928 Beckwith signed a two-year contract with Homestead, in its last year as an independent team.29 By late spring newspapers had begun to report his homer totals and compare them to those hit by the premier white slugger, Babe Ruth. One account in early June stated that Beckwith “seems to be Babe Ruth’s chief rival for home run honors this season. ‘Beck’ [has] 24 at this writing while Babe has hit 19. Beckwith added five to his total last Saturday at Uniontown, getting three in the first game of a double header and two in the second. He also hit a single and scored six runs in the bargain bill.”30 Of course Beckwith was competing against teams of various levels: semipro, minor, and major.

At least one pitcher made the same comparison that appeared repeatedly in the press. Beckwith “hit the ball father than anybody,” said Holsey “Script” Lee, who pitched against him … in the late 1920s. “For power he was the hardest hitter I ever saw…. Babe Ruth and Beckwith were about equal in power. Beckwith … used a 38-inch bat, but it looked like a toothpick when he swung it.”31 Ruth himself contended that “not only can Beckwith hit harder than any Negro ball player, but any man in the world.”32

When Beckwith hit two more homers later in June, a game report in another newspaper began with this comment: “Page Babe Ruth, king of swat, for John Beckwith, hard walloping shortstop of the Homestead Grays has driven out his 26th home run of the current season.”33 Just a week later, Beckwith hit his 30th tater against the Beaver Falls Elks, a line drive that sailed over the enclosure with plenty to spare.34 Beckwith hit number 32 against New Castle when he “crashed the ball over the center field fence, the blow being the longest hit ever made at Centennary (sic) field.”35 He hammered three homers in a game at Zanesville, Ohio. The first one was described as the longest that had ever been hit at the Zanesville park.36 Number 40 for Beckwith was another prodigious blast, this one in front of the home crowd at Forbes Field.37

By mid-September, Beckwith had 53 homers against various levels of competition,38 just ahead of Ruth, who slugged his 50th on September 15. Ruth would finish 1928 with 54 homers. How many did Beckwith hit? Baseball-Reference.com credits him with merely one in 19 games. Seamheads has him at four in 25 games. Yet according to one contemporary press report, he hit more than 60.39

Beckwith also played integrated offseason ball in the California Winter League. After a pedestrian (for him) 1927-28 campaign during which he hit .310 with five homers in 19 games, he had a dominating 1928-29, batting .485 with a league-leading 14 homers in just 27 games.40

The Homestead Grays played in the American Negro League in 1929. Finishing fifth on the team in plate appearances, Beckwith hit more homers (13) than all his teammates combined (12). Nevertheless, on September 7, the Grays traded the team’s only power hitter to the Lincoln Giants for George Scales.41

Beckwith spent 1930 with the New York Lincoln Giants playing other major-league level eastern independent clubs, according to Seamheads.com. Although he appeared in just 23 games while sharing time at first base with 46-year-old John Henry Lloyd, Beckwith turned in a stupendous .487/.537/.905 slash line, slightly exceeding Turkey Stearnes’ .425/.506/.904. A 1956 newspaper story reported that Beckwith hit 65 homers in 1930. In 1931 Beckwith went back to Baltimore, playing right field and hitting 12 of the team’s 19 homers.

Beckwith played for the Newark Browns in 1932 and the New York Black Yankees in 1933. In the former season, Beckwith managed Newark to four losses before the team folded; in the latter, Seamheads shows him playing in just 16 games and credits him with two homers, but a late-season newspaper story said he had hit 51.42

Beckwith split time in 1934 between the Black Yankees and Newark Dodgers. He appeared in limited action for the 1935 Homestead Grays, and for the 1936 and 1937 Brooklyn Royal Giants. The statistical record ends there for Beckwith, by then 37.

After his playing days ended Beckwith stayed involved with sports in the New York area. In 1941 he ran an independent club out of New York City43 or White Plains. “It is a mixed team—white and colored. Beckwith informs us that he has a first baseman under option with one of the Chicago clubs…. Cum Posey often talked about this mixed team combination, and now Beckwith is trying it out.”44

In 1953, Beckwith worked as a security guard at a radio manufacturer in New York.45 He died on January 4, 1956, survived by his wife Dorothy Beckwith and his brother Stanley.46

Beckwith leaves a complicated and incomplete legacy. The total number of homers he may have hit in a peak season or over his career remains uncertain. Likewise, we do not know how many fewer homers Ruth would have hit if he had to face the top Black pitchers of his day rather than just those he saw in the segregated American and National Leagues.

Beckwith played all over the diamond – he appeared in at least two games at eight of the nine positions (he never played center field). The conventional wisdom suggests that this versatility derived more from a lack of good glovework rather than a widely varied skillset. Even so, he had nearly as many top seven seasons in defensive WAR (four) as he did in offensive WAR (five).

Beckwith had a winning (63-53) record as a manager, but a reputation as a brawler and a difficult player to manage. But one of his former skippers had a completely different conception of Beckwith that he shared a few years after the end of Beckwith’s career. Cum Posey wrote in 1939, “John Beckwith was one of the easiest men to handle, and one of the game’s greatest players. Beckwith did not like to catch regularly; preferred to play with a club when he could play infield. That was why he played with so many different clubs in his prime. It was not his disposition.”47

Analysts likewise have not known what to make of Beckwith. Of interest, given his comment about how Beckwith did not like to catch, in 1940 Posey classified him as one of the three greatest Black catchers of all time.48 Historian Robert Peterson lists Beckwith among the best five shortstops of Black baseball. Bill James ranks Beckwith as the sixth best Black third baseman. The fact that a leading Negro League manager, historian, and sabermetric pioneer rated Beckwith so highly at three different positions underscores his distinctive and distinguished career.

In 2005 Beckwith was one of 39 people listed on special ballots aimed at selecting prominent Negro Leaguers and pre-Negro League figures for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was not one of the 17 chosen in February 2006. Had he been born in 1950 rather than 1900, Beckwith would surely have received the broader recognition that he deserved. He also might well have a plaque hanging alongside baseball’s immortals in Cooperstown. Beckwith may yet receive the game’s highest recognition should the Classic Baseball Era Committee make him eligible when it meets for the first time in the fall of 2024.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Dana Berry. Thanks to Adam Darowski for alerting the author to Beckwith’s California Winter League record.

Notes

1 Thanks to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for scanning the Hall’s file on Beckwith. The quotation in this paragraph and the information in the subsequent one comes from an undated and unattributed document in this file entitled “CHRISTOPHER ‘JOHN’ BECKWITH Family History.”

2 “Y.M.C.A. Swimming Pool Ready,” Chicago Defender, August 23, 1913: 3.

3 “Beckwith Would Like to Play for Cole’s Giants,” Chicago Defender, January 21, 1933: 9.

4 At least one newspaper article claimed that Beckwith batted from both sides of the plate. “Beckwith Signs to Play with Homestead Grays In 1924,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 22, 1923: 6.

5 John Fredland, “May 22, 1921: Chicago Giants’ John Beckwith hits first home run over fence at Redland Field in Cincinnati,” SABR Games Project, sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-22-1921-chicago-giants-john-beckwith-hits-first-home-run-over-fence-at-redland-field-in-cincinnati/ (last accessed December 22, 2023). “5,000 See Beckwith Knock Ball Over Wall for Homer,” Chicago Defender, May 28, 1921: 11.

6 Russ J. Cowans, “Russ’ Corner,” Chicago Defender, January 14, 1956: 18.

7 Mark Chiarello & Jack Morelli, Heroes of the Negro Leagues (New York: Abrams, 2007), 20.

8 “Beckwith Signs to Play with Homestead Grays In 1924,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 22, 1923: 6.

9 “Beckwith Released by Homestead Grays,” New Journal and Guide, June 28, 1924: 4. “Beckwith is Released by Homestead Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 21, 1924: 6.

10 “Sports Mirror,” Afro-American, March 28, 1925: A9.

11 “Pete Hill Again to Manage Sox,” Afro-American, October 24, 1924: 6.

12 “Among Ball Players,” Afro-American, November 22, 1924: 5.

13 “The ‘Four Horsemen’ of the Black Sox,” Afro-American, July 25, 1925: 6.

14 “Charleston Ties Beckwith for Home Run Honors,” Afro-American, August 8, 1925: A7.

15 “Sox and Giants to Lock Horns Sunday,” Afro-American, August 8, 1925: A7.

16 “John Beckwith Quits Black Sox and Leaves for Chicago,” Afro-American, August 29, 1925: 7.

17 “Beckwith Leaves for Cuba,” Afro-American, November 8, 1925: A7.

18 “Beckwith Loses His Mother,” Afro-American, December 5, 1925: 3.

19 “Beckwith Will Be Banished from Organized Baseball,” Afro-American, March 20, 1926: 8.

20 “Beckwith Returns to the Sox,” Afro-American, May 1, 1926: A8.

21 “Beckwith Suffers Torn Ligaments,” Afro-American, June 19, 1926: 7.

22 “John Beckwith Is Traded to Harrisburg,” Afro-American, July 10, 1926: 8.

23 “Cooper Leaves Sox, Goes to Harrisburg,” Afro-American, July 17, 1926: 12.

24 “Hot Stove League,” Afro-American, January 8, 1927: 14.

25 “Beckwith Will Manage Harrisburg,” Chicago Defender, January 22, 1927: 10.

26 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots Press Box & Ringside,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 5, 1927: A5.

27 “Beckwith, Charleston Expect to Lead League in Home Runs,” Afro-American, May 7, 1927: 14.

28 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1984), 232.

29 “Beckwith Signs Two Year Contract with Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 25, 1928: A4.

30 “Following the Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 9, 1928: A5.

31 John Holway, “The Black Bomber Named Beckwith,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1976, sabr.org/journal/article/the-black-bomber-named-beckwith/ (last accessed December 26, 2023).

32 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 185.

33 “Page Babe Ruth, John Beckwith Raps Out No. 26,” New Journal and Guide, June 16, 1928: 6.

34 “Grays-Beaver Falls Divide Double Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 23, 1928: A4.

35 “New Castle Loses to Homestead Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 30, 1928: B6.

36 “Grays Beat Zanesville by 9-3 score,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 21, 1928: B4.

37 “Grays Win Both Games Saturday,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 4, 1928: A4.

38 “Following the Grays,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 15, 1928: A6.

39 “Posey Denies Dihigo, Wilson, Beckwith Deal,” Afro-American, February 2, 1929: 10.

40 William McNeil, The California Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 250.

41 “Sport Review of the Year 1929,” Afro-American, January 4, 1930: 12.

42 “Beckwith Is Still Leading the Stars in Home Run Hits,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1933: 9.

43 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 5, 1941: 17.

44 John L. Clark, “Wylie Avenue,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 16, 1941: 18.

45 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, June 14, 1953: C1.

46 “Beckwith Rites Held In New York,” Chicago Defender, January 14, 1956: 17.

47 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 24, 1939: 15.

48 Cum Posey, “National Leaguers Dominate All-American,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 2, 1940: 17.

Full Name

John Christopher Beckwith

Born

January 10, 1900 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

January 4, 1956 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.