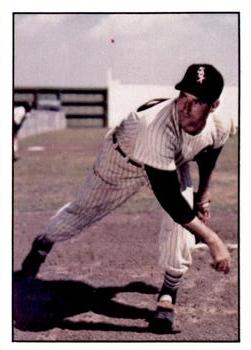

Sandy Consuegra

A glorious, romantic, and competitive era of Cuban amateur baseball was the early 1940s.1 During that time, there was a quartet of star pitchers: Conrado Marrero, Julio Moreno, Rogelio Martínez, and Sandalio Consuegra. All four entered the big leagues in 1950 with the Washington Senators. Consuegra – often known as Sandy in the U.S. – had the longest career and most wins in the majors. He was 51-32 with a 3.37 ERA from 1950 through 1957, with the clear peak being 1954. At the age of 34, he led the American League in winning percentage (.842) with a 16-3 mark for the Chicago White Sox.

A glorious, romantic, and competitive era of Cuban amateur baseball was the early 1940s.1 During that time, there was a quartet of star pitchers: Conrado Marrero, Julio Moreno, Rogelio Martínez, and Sandalio Consuegra. All four entered the big leagues in 1950 with the Washington Senators. Consuegra – often known as Sandy in the U.S. – had the longest career and most wins in the majors. He was 51-32 with a 3.37 ERA from 1950 through 1957, with the clear peak being 1954. At the age of 34, he led the American League in winning percentage (.842) with a 16-3 mark for the Chicago White Sox.

“[Manager Paul Richards] made a pitcher out of me,” Consuegra said that year through interpreter Buck Canel, the longtime Spanish-language broadcaster. “Before I came to the White Sox I was just a thrower. I threw a fastball and a curve and that’s all. As soon as I came over here Richards taught me how to throw a palmball and a sinker. Now I throw them quite often, mixed with my fastball and curve, and I have confidence that I can win.”2

Consuegra was a swingman, a role that has vanished with five-man rotations and specialized bullpens. He started 71 times in 248 appearances in the majors. He had only 26 saves, since that was not the focus for relievers in his time. He got batters to put the ball in play. In 809⅓ innings pitched, he struck out just 2.1 men per nine innings – but his walk ratio was 2.7, he allowed almost exactly one hit per inning, and he kept the ball in the park, giving up just 43 homers. Les Moss, who caught the Cuban with the White Sox in 1955-56, offered further insight. “Little Sandy Consuegra [he was 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds] was a pretty good pitcher who fooled batters with an array of pitches, including an effective slider, and motions.”3

Sandalio Simeón Consuegra Castellón was born on September 3, 1920, on a sugar plantation in Potrerillo, Cuba.4 This is a rural town in a mountainous region in the central part of the island. Cuban baseball author Roberto González Echevarría wrote, “The name means little pasture land.” He added, “Consuegra … had a typically backwoods first name found who knows where by his parents.”5

In 2011 Sandy’s son Rogelio (Roger) told the story. “In Cuba most homes had a Catholic calendar and it gave the name of the saint for each day of the month. I must assume his name came from the calendar, as all his other brothers and sisters had similar ‘strange’ names.” Indeed, the feast day of San Sandalio (St. Sandila, a ninth-century Spaniard martyred by the Moors) is September 3. Roger Consuegra further related, “When I was born my mother refused to name me Sandalio and I was going on the fifth day with no name. That afternoon Rogelio Martínez and Julio Moreno were facing each other, and they agreed I would be named after the winning pitcher. Deportivo Matanzas won, thus my name is Rogelio.”

Consuegra got his nickname (Potrerillo) in Cuban ball from his hometown. Much the same was true of Rogelio Martínez, who was dubbed “Limonar” for the name of the town where he first played.6 Manolo de la Reguera, the famous Cuban sports commentator, was responsible for Consuegra’s nickname and those of many other players.7

Sandalio, who was one of five boys and six girls born to Sotero Consuegra and Luisa Castellón, worked on the family’s 50-acre farm. He went to an elementary school in the countryside.8 The youth played ball after work and on weekends. After a while he and his friends came up with a team to play in a local league on cow pastures turned into baseball fields. He eventually moved on in 1935 to play with Cumanayagua, a larger town a few miles out.9

Roberto González Echevarría wrote, “A significant development in the thirties and forties was the emergence of players, mostly pitchers, from the provinces … white guajiros – country bumpkins.” The foremost of these “revered amateurs and later professionals” was Conrado Marrero, El Guajiro del Laberinto, but “Jiquí” Moreno was a distinguished runner-up, while Martínez and Consuegra weren’t far behind. In their amateur days, all four “often appeared in magazines, sometimes even on the covers.”10 It seemed as if it was almost compulsory in those days for Cuban men to sport pencil mustaches, like Hollywood stars of the time (Clark Gable, Errol Flynn, Ronald Colman, et al.)

After beginning his amateur career in Cumanayagua, Consuegra then played with Regiment 7 of the Cuban Armed Forces from 1936 through 1940. Roger Consuegra recalled, “At age 16, my father decided he wanted out of their rural existence and one day after work buried his mocha (a machete to cut sugar cane) in a wood column in the porch of the main house. According to him, he told my grandfather he was through with farming and was going to join the armed forces (Regiment 7), where he played ball and rode with the equestrian teams for the regiment.

“That mocha remained buried in that wood column until the day my grandfather died and I remember hearing that story many times. Eventually the one farm became seven and until 1960 the Consuegra clan’s baseball team played their baseball every time they could.”

Upon returning from Regiment 7, Consuegra spent a year with Sancti Spíritus. From 1942 to 1945 he was with Deportivo Matanzas. He also appeared twice in the Amateur World Series for Cuba. In 1943 he was 1-1 with a 3.44 ERA. In 1944 he was 1-0 with a 1.00 ERA11

White-only social clubs dominated the Cuban amateur scene – yet the level of play was high. Cuban baseball expert Peter Bjarkman described it as “a thriving tradition that grew up alongside Havana’s pro league and that, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, actually outstripped the pro game in island-wide popularity and fan stature.”12 Cuban all-star teams of the day also made a good showing against major leaguers. After the Boston Red Sox lost such a game in 1941, manager Joe Cronin reportedly said, “They may be amateurs, but many are better than our players.”

Consuegra started as a center fielder for Deportivo Matanzas.13 He began his transition to the mound in his first season there, 1942, going 3-1 (although Roberto González shows him with five victories). The 1943 season was noteworthy; at least one other expert, César López, viewed it as the best-quality season for the Cuban amateur league. It was a great race between Círculo de Artesanos, starring Jiquí Moreno, and Deportivo Matanzas. Amateur league games took place just once a week, and Moreno started virtually every Sunday for Artesanos. By contrast, Matanzas relied on three pitchers: Limonar Martínez, Consuegra, and Ángel “Catayo” González. The trio was known, without much imagination, as Los Tres Mosqueteros – The Three Musketeers.14

Given the schedule, one wonders how they stayed sharp, but manager Tomás “Pipo” de la Noval did not use them in rotation – rather, he gave them each three innings a game.15 González Echevarría called them “the best staff ever in Cuban amateur baseball.”16 He added, “All three were also feared batters.”17

Heading into the season’s final week, Matanzas had a record of 22 wins, 5 losses, and one tie. Artesanos was half a game back at 22-6. Jiquí Moreno struck out 14 (including eight in a row) to put his team ahead in the win column, but Matanzas responded with a victory of its own to take the title, as Martínez and Consuegra combined on a two-hitter. Consuegra’s record that year was either 11-2 or 9-1; his sparkling 0.97 ERA led the league.18

Círculo de Artesanos won the 1944 amateur championship, despite Consuegra’s 11-4 record. In 1945, though, he stepped forward as the primary pitcher for Deportivo Matanzas, leading them to another title with a spectacular performance. According to statistics provided by Conrado Marrero’s grandson Rogelio, he was 24-2, with a 1.39 ERA. This suggests that neither Limonar Martínez nor Catayo González was with the club any more. (The amateur circuit suffered from the loss of many players after 1944.) The Consuegra family does not have specific knowledge, but Roger Consuegra said, “Those were very happy years for him and he always drifted back to them in his conversations.”

Potrerillo was supposed to make his debut in US pro ball that year, having signed with the Minneapolis Millers, which were then unaffiliated. The Millers had brought in a number of other Cubans, including pitcher Isidoro “Izzy” León.19 As The Sporting News wrote that May, “Manager Rosy Ryan, catcher Jack Aragon, and other members of the club’s Cuban contingent stormed the telegraph offices to bombard Sandalio Consuegra with wires urging him to report. Consuegra, who is rated a better pitcher than León, failed to report with the other Cubans because he wasn’t sure he could make the grade.”20 Then again, he could have been in need of rest after the amateur league season, even though the games were played only once a week on Sundays.

The amateur status of these athletes was nominal, though, as columnist Roberto Rodríguez de Aragón wrote in his tribute to Limonar Martínez after the latter’s death in 2010. Around 1944 or so, Havana Reds manager Miguel Ángel “Mike” González offered Limonar and Consuegra a contract for 125 pesos a month to pitch for his team. They laughed and said that they made more than that for pitching one good game, thanks to the gifts of fans! They hastened to thank González, though, since he was a man of much respect.21

In the winter of 1945-46, Potrerillo turned pro at last, joining Tigres del Marianao of the Cuban Winter League. He got into five games and was 2-0 with a 2.86 ERA. The following spring, he made a decision that strongly influenced the course of his career: He went to Mexico. The 1946 season was when wealthy Jorge Pasquel made his push to put the Mexican League on the same level as the majors, fueled by higher salary offers. For Hispanic players, though, language and a more similar culture were also good reasons.

Consuegra went 14-13, 4.72 for the Puebla Pericos in 1946; that staff also featured 20-game winner Sal Maglie. Consuegra followed with 8-11, 3.06 marks for Marianao that winter. In 1947, the Havana Cubans – then a Class C farm club of the Washington Senators – wanted Sandalio to join their staff. If he had come, Consuegra would have joined Marrero, Moreno, and Martínez. Instead, another Cuban pitcher, Tomás de la Cruz, persuaded him to go back to Mexico. Havana club president Merito Acosta pressed charges against Consuegra, seeking damages of $1,600. “Acosta said he took the necessary steps to have Consuegra reinstated [since the Mexican League had become an “outlaw” circuit], signed him and advanced money to him.”22 With Puebla again, Consuegra trimmed his ERA to 3.36 while winning 10 and losing 10.

Cuba had a new league in the winter of 1947-48: La Liga Nacional, or Players’ Federation League. Consuegra started with Santiago, but after that club disbanded on December 15, he went to Leones. His overall record was 13-8, 3.76. The league completed the season but was defunct thereafter. That winter Consuegra played alongside Sal Maglie, Max Lanier, and others who became outlaws for jumping from the majors to Mexico in 1946. This had an ongoing effect on his ability to play in Organized Baseball – and many winter leagues – until the ban was lifted.

Consuegra went back for a third summer in Puebla in 1948 (8-5, 2.67) – taking a hefty pay cut to do so.23 As another part of its belt-tightening measures in the post-Pasquel era, the Mexican League folded two franchises in August. Consuegra went back to Cuba, either uncertain that the season would finish or fearing a further pay cut to offset the devaluation of the Mexican peso.24

Consuegra had also applied for reinstatement to Organized Baseball that summer, with an eye toward playing in the “proper” Cuban pro league that winter.25 His request was not granted – he went back to Mexico to play in a little-known winter circuit, La Liga Peninsular, on the Yucatán, 120 miles west of Cuba. With the club Cardenales de Motul, he led the league with a 1.33 ERA while going 8-2. His friend and fellow Cuban, outfielder Roberto Ortiz, won the Triple Crown for the Cardenales, who were the league champion.26

For the summer of 1949, Consuegra went to Venezuela, where La Liga Occidental (the Western League) was then operating in the summers. Up to that point, this circuit and the Venezuelan winter league had steered clear of ineligible players. With Gavilanes de Maracaibo, the Cuban starred again, posting a 14-3 record. In early June 1949, Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler issued a general amnesty to the outlaws. George Trautman, president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, put Potrerillo back in good standing. 27

La Liga Occidental’s season ended in July, and Consuegra finally became a member of the Havana Cubans. In 11 games, he was 6-5, 3.04. He might have made it to the majors that summer, but “when the Nats [Senators] wired for Consuegra to report, somehow, between Washington and Havana, the orders got scrambled. Instead of Consuegra, another Cuban righthander, [Julio González], showed up.”28

That fall, in the Inter-American Baseball Tournament at Caracas, Consuegra threw a no-hit, no-run game against host team Venezuela. Center fielder Pedro Pages preserved the gem in the ninth inning with a catch after a long run.29 The winter of 1949-50 was Sandalio’s busiest in Cuba. He was 13-12 for Marianao, leading the league in innings pitched and losses.

After a disagreement with Senators owner Clark Griffith, Consuegra started the 1950 season in Havana again. “He had incurred a $3,000 debt by signing with a Venezuelan team during the winter. He said that he had spent the $3,000 ‘bonus’ and asked Griffith to make that sum up to him. Griffith didn’t hesitate a moment. He just handed the Cuban a one-way ticket back to Havana.”30

In June 1950 Consuegra made it to the majors at last, following a hot start with the Cubans (8-2, 2.15 in 11 games). Roberto Ortiz, who had become a backup outfielder with the Senators, praised Consuegra and helped iron out differences with Griffith. Sandalio made his debut on June 10 at Griffith Stadium. “With his sneaky fastball and unorthodox windup,” he threw a rain-shortened five-inning shutout against the White Sox. The St. Louis Browns shelled him in his next outing, but Consuegra won his next two, going all the way and then eight innings. That July, The Sporting News wrote a feature about him, accompanied by a picture of the hurler making a zany face and a goose-egg hand sign.31

Consuegra lost his last three decisions to finish at 7-8, 4.40 in 21 games (18 starts). He pitched poorly in 17 games in Cuba that winter (4-8, 6.10), and Clark Griffith instructed him to stay out of winter ball for fear of sapping his strength.32 Sandy started the 1951 season with a bang for the Senators, throwing three straight complete-game victories and allowing just one run in each.

That May, The Sporting News ran a full-page feature on Conrado Marrero and Consuegra. As was typical of the time, their accents were parodied, but one quote shined through nonetheless. In his first start, Consuegra retired Mickey Mantle the first four times he faced him, twice by strikeout, before giving up a triple in the ninth. He told reporters (through translator Willy Miranda) that none of the Yankees gave him any trouble. A reporter asked him, then, was Mantle lucky? “No, he no luckee. I fool heem four time, he fool me one time.”33

As the season wore on, though, Consuegra may have worn down. Manager Bucky Harris used him much more in relief (12 starts in 40 games), and he finished with numbers similar to 1950’s (7-8, 4.01). Consuegra did not pitch in the winter of 1951-52, and with the Senators in 1952, he started just twice in 30 games. He was effective in his limited action: 6-0, 3.05 in 73⅔ innings.

Consuegra returned to winter ball in 1952-53, splitting the season between Marianao and the Cienfuegos Elefantes (6-9, 3.04). He pitched just four games for Washington in the early going in 1953. On May 12 the White Sox bought his contract for roughly $15,000. As Chicago columnist Edgar Munzel put it the following year, “[N]o one paid much attention to the little bowlegged Cuban. He was dismissed as just another second-flight bull pen pitcher who probably would be on his way elsewhere within a short time in Frantic Frankie Lane’s endless shuffling of material. The general understanding was that Sandy was a happy go-lucky Cuban who spent so much of his time on clubhouse gags that Washington finally decided to get rid of him. Furthermore, Consuegra already was 32. He wasn’t too strong, either. He lacked ruggedness and the Senators had several other Cubans like him on the roster.”34

Once in Chicago, Consuegra pitched well. Over the rest of the ’53 season, he was 7-5, 2.54 in 29 games (13 starts). Despite his limited English, he took active part in the clubhouse fun. There were three Cubans to keep him company: Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, Mike Fornieles, and Luis “Wito” Alomá. Because of his sharp nose and narrow features, his teammates called Consuegra ‘The Crow’ or ‘Chicken Head.”35 Munzel added, “He’s still the clubhouse gagster. … he’ll entertain his mates with imitations of other players that would make a professional actor envious.”36

Having skipped winter ball again in 1953-54, Consuegra may have been fresher in the spring of 1954. Manager Paul Richards said, “[He] will be our number three pitcher and I wouldn’t be surprised if he is our number two pitcher.”37 As the season unfolded, Richards was right in some important ways. Starting 17 games and relieving in 22 others, Consuegra was tied for second on the club in wins, along with Bob Keegan, behind 37-year-old ace Virgil Trucks. Along with his 16-3 record, Sandy led the club in ERA (2.69).

He also made it to the All-Star Game for the only time that July, as manager Casey Stengel named him to replace Mike Garcia of the Indians, who had broken a blood vessel in one of his fingers.38 He got shelled after replacing Whitey Ford in the top of the fourth at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. He got Alvin Dark to fly out, but then gave up four straight singles to Duke Snider, Stan Musial, Ted Kluszewski, and Ray Jablonski. When Jackie Robinson then doubled, that was all for Consuegra. All five runners scored, leaving him with a 135.00 ERA – the highest tangible number in All-Star history.39

Even so, as Roger Consuegra recalled, “The three things he considered most relevant in his years of baseball were that 24-2 season with Deportivo, the no-hitter in Venezuela with Pages’ catch as a highlight, and playing in that All-Star Game. At the time only a couple of Cubans had achieved the honor.”

“The Crow” finished second behind “The Big Bear” (Mike Garcia) for the ERA title; the race for both this and the best winning percentage featured some entertaining sidelights. Consuegra did not pitch from August 27 to September 18 – he was hospitalized with a severe case of hives. Pitching coach Ray Berres remembered the exchange between Sandy and Marty Marion, who had replaced Paul Richards as manager with nine games left on the schedule. “Me itch,” Berres quoted Consuegra as saying. “Marion says, ‘You itch here with us until the end of the season. Then you can go home and itch all winter.’”40

“A friend frantically informed [Consuegra] he still needed a few innings to reach the then-required total of 154 to qualify for the percentage title. Consuegra sprang into action.”41 He threw two-thirds of an inning at home on September 19. The following day, at Cleveland, he threw three scoreless innings, then on the 21st he ended the game by getting Dale Mitchell (always a tough out) to fly to right. That got him to 154.0 innings pitched on the nose, and he did not appear in any of the club’s remaining three games.

Meanwhile, Garcia held the ERA lead at 2.55, but he nearly coughed it up in the last game of the season, on September 26. He gave up four runs to Detroit in the first two innings, but – gunning for his 20th win of the season – wound up going 12 and allowing just two more runs to finish at 2.64.42

In his 154 innings – a big-league career high – Consuegra struck out just 31 and walked 35. He was 8-3 as a starter and 8-0 in relief. Another note of interest that year was Paul Richards’ tactical maneuvering. One of his favorite ploys when seeking better matchups was to station his pitcher temporarily in the field and then bring him back to the mound. On July 3 at Cleveland, he put Consuegra at third base while Morrie Martin retired Larry Doby. Richards might just as well have given Sandy the hook, though, because the Indians then tied the score at 3-3 and went on to win in 15 innings. “The proviso prohibiting pitchers from assuming a position other than pitcher more than once in the same inning was added to Rule 3.03 largely to thwart managers like Paul Richards.”43

After another winter off, Consuegra remained effective for Chicago in 1955: 6-5, 2.64 in 44 games (seven starts). Coming back to Cienfuegos that winter after two seasons away, he continued to pitch well, mainly out of the bullpen. The Elefantes won the league championship, and so in February 1956, he went to the Caribbean Series for the first and only time. In his lone appearance, he lost to Puerto Rico (the only loss for the Cubans in the round-robin tournament).

Consuegra’s performance fell off with the White Sox in 1956 (1-2, 5.17 in 28 games). In late July the Baltimore Orioles – where Paul Richards had jumped in September 1954 – purchased his contract. Consuegra didn’t want to go to Vancouver in the Pacific Coast League, which was then Baltimore’s top affiliate. “Too far place,” he pleaded with Richards, who then arranged for him to play with the Havana Sugar Kings (in the Cincinnati Reds chain).44 The Orioles called Potrerillo up in September, and he got into four games.

Back with Baltimore in 1957 after just 10 winter games with the Elefantes, Consuegra made just five appearances through early May. On May 14 the New York Giants purchased him from the Orioles as Baltimore got down to the 25-man roster limit. Sandy came out of the bullpen four times for the Giants. His final game in the majors was May 28, 1957.

Roger Consuegra said, “The hitter he could not get out regardless was Forrest Jacobs of Philadelphia. I think he broke up a no-hitter once. Also, Larry Doby was not an easy out for him.” Indeed, Spook Jacobs – who also played a good deal in Cuba – was 7-for-18 (.389) in the majors against Sandy, including the Athletics’ only two hits on May 3, 1954. Doby was 12-for-31 (.387) with four homers.

In June the Giants sold Consuegra’s contract to Vancouver. This time he went to the Pacific Northwest, and he pitched well for the Mounties: 7-1, 1.99 in 44 games, all out of the bullpen. Manager Charlie Metro said in his memoirs, “Sandy Consuegra was a fine relief pitcher in the big leagues. He had a very good motion, very smooth, like he wasn’t even trying. He could save games with the best of them.”45

Consuegra wrapped up his winter career in 1957-58 with Cienfuegos. His grand totals in Cuban leagues: 52 wins, 55 losses and a 3.65 ERA. He stayed in Cuba to start 1958, as Havana owner Bobby Maduro brought the local favorite back to play for the Sugar Kings, trading former Brooklyn Dodger Joe Hatten to Vancouver. Sandalio was 0-0 in seven games and then went back to Mexico after a decade away. He was “coaxed by a personal visit from Manager Reggie Otero [a fellow Cuban] to come from Cuba to join Monterrey.”46 In six games (five starts) for the Sultanes, he was 2-2 with a 5.91 ERA. For a while that summer he unexpectedly left and went home to Cuba, but the Monterrey club reinstated him from the disqualified list.47

After that season, Consuegra retired. As of 1954, he had owned five homes in Cuba and planned to purchase more, living off the income from them.48 He eventually built 11 houses and bought one small farm (60 acres) in his family’s hometown of Matanzas.49 Between 1958 and 1960, Consuegra also managed the local stadium there. “This was a source of great pride,” said his son Roger, “as that is the place where not only he played with Deportivo but also the first ball game in Cuba was played (Palmar de Junco). It still stands, has been refurbished and named part of the National Heritage.”50

When Fidel Castro seized power in 1959 and set about redistributing the nation’s wealth, Consuegra lost his real estate holdings. “All that was wiped out within the first eight months,” said Roger. “I was the first one to leave Cuba, then my sister and eventually mom and dad. We all arrived in Miami and have lived and died here. I remember when he came over, they allowed him to keep two dimes in his pocket, which he used to call me to pick him up at the airport. I’d be remiss if I did not mention another Cuban ballplayer, Roberto Estalella, who opened his home to us until my father found a job.”

Consuegra made a brief comeback in 1961 with Charlotte, a Class A farm club of the Minnesota Twins. He gave up three earned runs in 6⅓ innings (4.26 ERA) in two games. “The comeback at Charlotte was an impromptu decision to make some money,” said Roger, “but he was 41 and a bit down on his luck and his arm was dead. I remember him coming back on a Greyhound bus and not wanting to talk about the experience.”

“His first job, working at the cargo department of an airline, lasted many years. It was also made possible by another ballplayer, Francisco Campos. After that he worked as a security guard until age 62. His inability to speak English did not help, as I recall taking calls from the Houston Colt .45’s – Paul Richards – and hearing about offers for jobs as scout and trainer for Latin pitchers. But it meant also a move to Houston, and my mother said no and that was the end of the story.

“My father always tended to take under his wing Cuban ballplayers arriving in the big leagues and our house was an open house for many budding players. Unfortunately, he felt shunned by those same individuals he helped or befriended and that made him become very distant to his passion, baseball.”

Nonetheless, Consuegra was one of many former Cuban pros in the Miami community who gave his time to Los Cubanitos, the youth baseball program founded by Emilio Cabrera in 1961. The Facebook page that commemorates Los Cubanitos shows photos of Sandalio – “a nice man who loved to teach and loved the game” – with 1969 and 1970 squads. “He enjoyed Los Cubanitos,” said Roger, “and Emilio Cabrera was one of the few he called friend as time went by.

“He also played in several Cuban old-timer’s games, or Juegos de Recuerdo. He enjoyed these while they lasted and even played center field in one of them.” The Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile) inducted Consuegra in 1977.

Sandalio Consuegra married Blanca Ramos on July 28, 1943. They had three children: Rogelio, Silvia, and Norma. “My parents were married for 60 years,” said Roger, “and when my mother died in 2003, it zapped his will to live. He became bitter and felt alone in spite of having his children and grandchildren around. He died after falling and breaking his hip.” The end came on November 16, 2005, in Miami.

“He never mentioned how he would like to be remembered,” said Roger, “but I think he would be quite happy to know that many folks who knew him, think of him as one of the most humble and affable persons they knew. To this day I am surprised at the amount of people who remember him – or, hearing my last name, ask if I am related to the ballplayer.

“Recently an article came out naming the greatest 15 pitchers in White Sox history and he was number 15. That would really have made his day.”51

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Rogelio Consuegra, Silvia Consuegra-Vélez, and the entire Consuegra family for participating in this remembrance of Sandalio Consuegra. Continued thanks to Rogelio Marrero in Cuba (amateur statistics).

Sources

In addition to the sources in the notes, the author also consulted Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference.com, cubanball.com, santopedia.com; catholic.org/saints, and these publications:

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, ed. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011).

The Sporting News Baseball Register, 1956.

Notes

1 Cuban amateur ball in the post-revolution era can certainly be termed glorious and competitive as well (perceptions of “romantic” may differ).

2 John C. Hoffman, “Plantation Pitcher,” Baseball Digest, September 1954: 17.

3 Danny Peary, We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion Books, 1995).

4 Hoffman: 15. Note that baseball references have shown his mother’s family name as Castelló, but the family has corrected this.

5 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 220.

6 Ibid.

7 E-mail from Roger Consuegra to Rory Costello, November 14, 2011.

8 Hoffman: 15.

9 Roger Consuegra email.

10 González Echevarría, 220.

11 Peter C. Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007).

12 Peter C. Bjarkman, Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 6.

13 Hoffman: 17.

14 Marino Martínez Peraza, “Un Mosquetero del Deportivo Matanzas.” El Nuevo Herald, May 29, 2010.

15 Jorge Alfonso, “Amplitud del Horizonte (II).” Béisbol Cubano website (http://cubasi.cu/beisbolcubano/historia/amplitud-del-horizonte-II.htm), April 9, 2007.

16 González Echevarría, 232.

17 González Echevarría, 246. In the majors, Consuegra hit .170 (37-for-218, with two doubles).

18 http://cubalaislainfinita.com/2011/09/03/atletas-cubanos-sandalio-simeon-castello-consuegra-%E2%80%9Csandy-consuegra%E2%80%9D/.

19 Halsey Hall, “Millers Land Cuban Cargo,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1945: 9.

20 The Sporting News, May 3, 1945: 18.

21 Roberto Rodríguez de Aragón, “Rogelio Martínez, el grandioso ‘Limonar,’” Libre Online, June 9, 2010 (http://libreonline.com/home/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10799:rogelio-martinez-el-grandioso-limonar&catid=20&Itemid=18).

22 “Cuban Press Raps Jump by O.B. Player to Mexico,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1947: 16.

23 Pedro Galiana, “Mexican Jumpers Balk Over Pasquel Pay Cuts,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1948: 21.

24 Jorge Alarcon, “Six Mexican Loop Players Jump to O.B.,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1948: 29.

25 “De la Cruz Plans 3-Nation Series,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1948: 1.

26 Menéndez Torre, Jorge. “El ‘Potrerillo’” (http://poresto.net/ver_nota.php?zona=yucatan&idSeccion=19&idTitulo=116410).

27 “Cubans Add Mexican Jumpers,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1949: 32.

28 Herb Heft, “Ortiz Speaks and Consuegra Makes Batters Talk Spanish,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1950: 7.

29 “Consuegra Pitches No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1949: 52.

30 United Press, “Sends Hurler Home,” April 7, 1950.

31 Heft.

32 Shirley Povich, “Nats Inviting Batterymen to Camp Feb. 20,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1950: 13.

33 Morris Siegel, “Senors ‘Peetch Gude’ for the Senators,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1951: 3.

34 Edgar Munzel, “Hats Off! Sandy Consuegra,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1954: 17.

35 Hoffman: 16.

36 Munzel.

37 Hoffman: 15.

38 Associated Press, “Consuegra Takes Garcia’s Place,” July 12, 1954.

39 Danny Jackson (1988; 1994) and Jason Bere (1994) both gave up runs while failing to retire a batter – and thus recorded infinite ERAs.

40 Lew Freedman, Early Wynn, the Go-Go White Sox and the 1959 World Series (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009), 52.

41 Bob Vanderberg, “A Fond Adios to Sandy Consuegra,” Chicago Tribune, December 29, 2005: Sports-2. Roger Consuegra said, “This beautiful writeup would have made him proud and appreciative.”

42 Even if Garcia had gotten the hook after two innings, though, he still would have edged Consuegra at 2.68.

43 David Nemec, The Official Rules of Baseball Illustrated (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2006), 39.

44 “Consuegra Going to Cuba,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1956: 23.

45 Charlie Metro and Thomas L. Altherr, Safe by a Mile (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 206.

46 Miguel A. Calzadilla, “Lions Begin Climb as Tigers Stumble,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1958: 57.

47 “Tigers’ Rookies Take Lumps,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1958: 35.

48 Hoffman: 16.

49 Email from Roger Consuegra to Rory Costello, November 14, 2011.

50 To clarify, the phrase “first ball game in Cuba” should be interpreted as “the first to achieve press coverage and a printed box score in the newspaper.”

51 Alex Rostowsky, “Chicago White Sox: Ranking the 15 Greatest Pitchers in Franchise History.” Bleacherreport.com (http://bleacherreport.com/articles/836841-chicago-white-sox-ranking-the-15-greatest-pitchers-in-franchise-history).

Full Name

Sandalio Simeón Consuegra Castellón

Born

September 3, 1920 at Potrerillo, (Cuba)

Died

November 16, 2005 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.