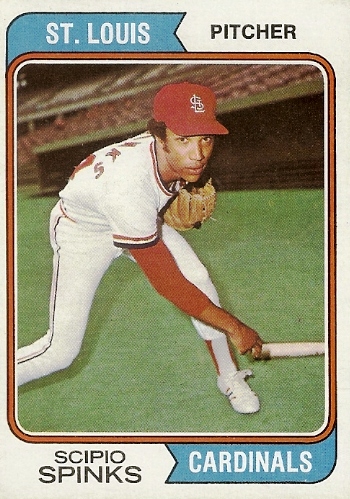

Scipio Spinks

Whenever the subject of best baseball names comes up, Scipio Spinks is sure to be on the short list. A classic wild flamethrower, Spinks was breaking through to success in 1972. If he hadn’t torn up his knee in a collision with Johnny Bench, he would have more to show than a career record of 7-11 in the majors. Yet this high-spirited character has spent a lifetime in baseball, coaching and scouting for more than three decades since his playing days ended. “From the first day I signed,” said Scipio in 2009, “I knew baseball was my life. Even as a kid I wanted it.”

Whenever the subject of best baseball names comes up, Scipio Spinks is sure to be on the short list. A classic wild flamethrower, Spinks was breaking through to success in 1972. If he hadn’t torn up his knee in a collision with Johnny Bench, he would have more to show than a career record of 7-11 in the majors. Yet this high-spirited character has spent a lifetime in baseball, coaching and scouting for more than three decades since his playing days ended. “From the first day I signed,” said Scipio in 2009, “I knew baseball was my life. Even as a kid I wanted it.”

Scipio Ronald Spinks was born on July 12, 1947, in Chicago, Illinois. His father shared the unusual given name, which is a long-running tradition in the Spinks family. “Every firstborn son on my father’s side has been named Scipio [after the great Roman general who defeated Hannibal],” he said. “The ‘c’ is silent, it sounds like ‘sip.’” Spinks was called Ronald as a youth to distinguish him from his father. “It was Ronnie until I graduated from grammar school.”

The elder Spinks was in the Navy, worked on the railroad, and then became a postal clerk. He worked at the post office until retirement. His wife, Lorraine (née Cartwright), worked at Illinois Bell Telephone, then as a legal secretary until she retired. Scipio had one younger brother and one half-sister — “I think. Papa was a rolling stone!” In addition, former Cincinnati Reds pitcher Wayne Simpson is his cousin.

“Ronnie” Spinks grew up on Chicago’s South Side, which is White Sox territory, yet he was a Cubs fan. “It was Ernie Banks, of course. He lived five blocks from where I lived.” Spinks also played football and basketball, but baseball was “the one I loved the most and the easiest for me to play.” From an early age, he dreamed of playing in the big leagues. As a child he played in the local Little League and then in the West Park Manor Babe Ruth Baseball League. As a 1968 article in the South Side Bulletin described it, this was a shoestring operation kept afloat by a few dedicated men, in particular one named Anthony Overstreet.1

Spinks attended St. Rita of Cascia High School for his freshman and sophomore years. Three other major leaguers also went to this all-male Catholic prep school on the South Side: Nick Etten, Ed Farmer, and Jim Clancy. Scipio then went to Harlan High for his final two years.2 “The tuition at St. Rita was too high to send two sons there,” he recalled. “Since I was the oldest, I transferred to Harlan. Harlan had no baseball team at the time.”

As a result, in his mid- to late teens, Spinks played Connie Mack ball with the Jackson Park Orioles. He also played semipro ball on weekends. After graduating from Harlan, he went on to Woodrow Wilson Junior College in Chicago (renamed Kennedy-King College in 1969). He went 7-2 for the Red Raiders, leading his team to the city finals against Wright Junior College. In 1966, following his first year at Wilson, he signed with the Houston Astros.3 The scout was Walt Laskowski. “After I made it to the big leagues, everybody said they noticed me,” Spinks observed. “But the Astros were the only team I knew of.”

George Wilson, who supervised Scipio in the Connie Mack program, said, “Ronald is a big, strong boy and has all the tools. He is about 6-1, and he weighs just under 200 pounds [it was 185]. He has a real live fastball, a good curve, and excellent control.”4

Spinks reported to Bismarck-Mandan in the Northern League. When asked what it was like going from Chicago to North Dakota, he remembered, “They thought all the black guys were American Indians — cultural shock.” Only several weeks after he turned pro, on August 26, 1966, he set a Northern League record by striking out 20 in a game. The opposing pitcher for Sioux Falls that day, future Reds star Gary Nolan, fanned 17. Neither was around to get a decision, though, as Bismarck scored the game’s lone run in the 10th inning. A total of 41 men struck out.5

Scipio still remembers this game well. “I believe that . . . is still a record for nine innings for the most strikeouts by two pitchers. In the ninth inning, my manager, Tony Pacheco, told me, if I strike out the next three batters, he would buy me a steak dinner. Never got it.”

Spinks pitched mainly in relief that summer, going 1-1 with a 2.54 earned-run average, pitching 39 innings in 15 games. He whiffed 52, but also walked 26. That fall, an African-American newspaper group in Chicago, the Woodlawn Booster/South Side Bulletin, interviewed the “mild, rather humble” 19-year-old. His remarks captured a competitive spirit, though.

“I can warm up in the bullpen ’til doomsday but there’s something about having that hitter with that big stick waving at you, that turns you into steel, and makes you react to [the] pressurized presence of the moment. . . . It’s mysterious really. . . . But I really do love that pressure. . . . One of my coaches once told me that I was bad in the bullpen, but became a different pitcher once I got on that mound. . . . It’s for keeps then, I guess that is the whole point, isn’t it?” He added, “I really dig Mudcat Grant’s calmness, when the going gets tough. Man, I rate Grant over Sandy Koufax.” The article concluded with a description of how Scipio would pitch to Willie Mays.6

Despite what George Wilson said, control was a problem for the prospect. From 1966 through 1971 in the minors, he averaged 5.9 walks for each nine innings pitched. He also struck out 9.7 men and allowed just 7.1 hits, though.

Thus he advanced quickly, skipping Double-A ball except for one game in 1967. Another highlight of that year came in August, when the Astros called him up from Cocoa to start an exhibition game against the Texas League All-Stars. “Boy, was I nervous before the game,” Spinks said. “But I settled down and my fastball was moving. This was an opportunity I had to take advantage of. Mr. Grady Hatton (Astros manager) even told me ‘Good game’ before I left.”7 Among other future big-league sluggers, Scipio struck out Willie Crawford and Nate Colbert.

Scipio’s friends on the South Side sent him off to spring training 1968 with a banquet in his honor. He followed up with a nice year at Greensboro in the Carolina League (9-6, 2.27). He jumped to Triple-A Oklahoma City in 1969, and his record was poor on the surface: 7-11, 5.48. An emblematic game came on May 8, when he lost a no-hitter. It was the opener of a doubleheader at Omaha, so both games were seven innings. Still, Spinks packed in enough wildness in his six innings for a full twin bill. He let in his first run on a walk, a bad pickoff throw, and two wild pitches; the second came on two walks and a passed ball.8

Nonetheless, the Astros called him up when rosters expanded, and he made his big-league debut on September 16, 1969, at San Diego Stadium. After a shaky start — a walk, a single, and a passed ball — Spinks struck out the last four batters he faced in his two innings. Later that month, Sports Illustrated wrote, “Spinks . . . also established himself as a blithe spirit by stealing the feathery headdress from the Brave mascot, Chief Noc-A-Homa.”9

Returning to Oklahoma City in 1970, Spinks again lost more than he won (9-12), but his ERA improved to 3.30 and he struck out 153 while walking 77 in 158 innings. He also pitched five games for the Astros in May. That winter, he played for Cardenales de Lara in Venezuela, joining other Astros prospects such as Ken Forsch. He completed four of 12 starts, going 8-4 with a 2.60 ERA. He struck out 60 and walked 60 in 90 innings. Venezuelan baseball author Alfonso Tusa recalled hearing that batters stood well off the plate when Spinks was pitching. Scipio remarked, “I was effectively wild in those days.”

The experience helped him at Oklahoma City in 1971. His won-lost record was better (9-6) and the flamethrowing even more impressive: 173 Ks in 133 innings. Although the control issue flared up again, Houston called him up for five more games in September — including his first big-league win. At Atlanta Stadium on September 6, the Astros gave Spinks a 6-1 lead and he survived a three-run homer by Earl Williams to go all the way for a 6-4 victory.

On April 15, 1972 — Opening Day — the Astros traded Spinks and lefty pitcher Lance Clemons to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Jerry Reuss. Cardinals owner Gussie Busch had reportedly soured on Reuss’s mustache and contract demands.10 Astros manager Harry Walker said, “We thought Spinks might win between six and eight games for us. We think Reuss might win between 14 and 18.”11 Although Reuss did not fulfill the prediction that year, he had seven such seasons in his remaining 17 in the majors.

Initially, though, Spinks made the deal look good for the Cardinals. While he was just 5-4 in his first 15 starts, he suffered two tough losses to the Dodgers. On June 3, he lost a 1-0 duel at Dodger Stadium to Don Sutton. Ten days later in St. Louis, he lost 2-1 to Tommy John as Manny Mota stole home in the sixth inning to break up another scoreless tie. Scipio pitched six complete games, including impressive back-to-back outings on the road against the Mets — with a career-high 13 K’s — and the Phillies in late June. The rookie (he still qualified) had gone over .500, and he trailed only Steve Carlton and Tom Seaver for the National League lead in strikeouts.

On Independence Day of 1972, however, his fortunes changed. In the top of the third inning at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, Spinks singled. One out later, Luis Meléndez doubled, and the pitcher — whose speed had led manager Red Schoendienst to use him as a pinch-runner four times previously — steamed through a stop sign. He scored, but in the play at the plate, he tore ligaments in his right knee upon impact with Johnny Bench’s shinguards. Scipio missed the rest of the season.

Not long after his knee operation, Spinks welcomed the birth of a baby daughter named Terri Lynn. He and his first wife, Areda Tolliver, had met in Oklahoma City and continued to reside there; they were married in 1969.

Spinks reported to spring training 1973 in good health and typical form as a jokester. He remarked, “During my six years in the Astros’ chain, most of the managers thought of me as some kind of wise-guy hot dog who wasn’t serious enough to be a winning pitcher in the major leagues. Now that I’m with the Cardinals, where people have a sense of humor, I’m regarded as both a big-league pitcher and a guy who can keep the team loose with humor.” For example, he played with autograph seekers in camp by wearing number 20 as a Lou Brock impostor.12

Also on hand in camp was Scipio’s closest “teammate” — a large stuffed gorilla. He had bought the toy in a Houston hotel gift shop early in the ’72 season and dubbed it Mighty Joe Young. Clad in a Cardinals batboy uniform, Joe roomed with Spinks on the road and lived in his clubhouse locker at home. The pitcher had great fun investing his companion with human traits.13 Joe also proved popular for radio and TV show appearances, community meetings, and hospital visits.14 Ultimately the other Cardinals grew fond of the ape, but not before Joe suffered assorted indignities at their hands — Bob Gibson pulled off his nose, while the team hung him from the rafters in Pittsburgh. They also stuffed him in the clubhouse dryer before Scipio’s career day versus the Mets.15

Spinks made the St. Louis rotation again in ’73. He lost four of his first five starts, though, and was effective only in a no-decision against the Dodgers (also marked by his only big-league homer, off Al Downing). After missing most of May with a sore arm, he got his last major-league win, over Cincinnati, on May 29. He took only two more turns after that, which turned out to be his last appearances in the majors. “Sip strained his shoulder during his first start of ’73. Calcium deposits formed, causing Spinks to be placed on the disabled list June 15.”16

In an unusual move for the time, Spinks shaved his head to change his luck, as he had upon being traded in ’72.17 This time it didn’t work, though — once again, Spinks was done for the year. The Cardinals recalled him in September, with an eye toward giving him limited action, but he never got out of the bullpen.

Spring 1974 found Spinks just 26 and still well regarded. The Phillies considered dealing for him that March. “Yes, I like him,” said Paul Owens, then the Phillies’ vice president of player personnel. Manager Danny Ozark demurred, despite noting “one of the liveliest fastballs I’ve ever seen,” but shortstop Larry Bowa said, “I’d take a chance on him right now. He was faster than Seaver and wasn’t even airing it out.” Outfielder Bill Robinson concurred: “When he’s young and has that type of an arm, you have to take a chance on him.”18 Instead, the Cardinals traded the Chicagoan back home, receiving veteran outfielder Jim Hickman from the Cubs.

In a related deal, Spinks then sent Mighty Joe Young to Cardinals teammate Bernie Carbo, who had been traded to the Red Sox the previous October. The gorilla went on to new adventures in Boston, riding alongside the flaky outfielder in plane and train seats — and also surviving a near-immolation during a slump. “They were going to burn him!” Carbo remarked incredulously. “The whole club poured alcohol on Mighty Joe Young and were going to burn him, so I took him back home to Detroit.”19

Chicago sent Scipio down to Triple-A Wichita along with Dave LaRoche, in the last cut before the 1974 season began. Then, although the Cardinals’ doctors had assured the Cubs that the pitcher was healthy,20 he was able to pitch just 13 ineffective innings in eight games for Wichita. He stayed with the Aeros as their first-base coach.21

The Astros signed Spinks that winter but sent him to the Triple-A Iowa Oaks in March. After losing three starts and walking 14 in 10 innings, he was released. He notes, “I still had a torn triceps muscle that hadn’t healed yet.”

Scipio then got a chance with the West Haven Yankees in the Double-A Eastern League. That June, he remarked, “Playing in the minors is really no fun. The majors is where it’s at for a ballplayer. This is important to me because I want to get in a lot of innings and get back in shape. I’m throwing well now but I have to keep pushing myself to make sure I get back.”22

Spinks logged just 35 innings for West Haven, though, going 1-3, with a 6.17 ERA, in seven starts. That was his last summer-season action, although he did get a tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates in September 1976. Despite bruising manager Danny Murtaugh’s ankle with a pitch in the bullpen, Scipio was reportedly going to sign a contract with the Pirates.23 “They signed me and sent me to Instructional League, then back to Venezuela,” Spinks said.

Although the Venezuelan record books do not show any statistics for Scipio in the winter of 1976-77, he thinks there might be a gap in the records. At any rate, that was his last winter-ball experience. He had also gone 2-3 for the Arecibo Lobos of the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1974-75 while he was battling his sore arm. (Scipio’s second wife, Sandra Gómez, was from Puerto Rico. She worked for TWA as a flight attendant.)

The end of the line was at hand: “Finally in spring training [with the Pirates in 1977], I couldn’t throw any more.” The next year was when Scipio first became a scout, with the Astros. During a visit to Nicaragua that fall, he saw a talented young player named David Green, who signed with Milwaukee a few weeks later.24 “I liked him,” said Spinks, “but Walt Matthews, the senior scout, didn’t think he was good enough to sign.”

In 1980, Spinks was the pitching coach at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Among his pupils were two future major leaguers: Marvin Freeman and Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd. Freeman, who also grew up on the South Side of Chicago, later called Scipio his best coach. “He had some pro experience, and he got us ready mentally for the games.”25 Scipio added, “Oil Can still attributes his development to me. He was a joy to work with after he found out that I was there to help him.” Unfortunately, even though he did a good job and the players liked him, Spinks was at JSU for just that season. “It was back and forth with the coach, Bob Braddy. He said he had little money.” Scipio surmised that it may have been jealousy, however, “because of how I got along with the players.”

Spinks was out of pro baseball for some years, although he helped out at Texas Southern University. In 1989, he played for the Winter Haven Super Sox of the Senior Professional Baseball Association. The league was short-lived and Scipio’s stint was even briefer: five games with a 20.65 ERA.26 That same year, he joined the San Diego Padres organization as a scout. In 1993, he brought in his only major leaguer to date: Glenn Dishman from Texas Christian University, who pitched 33 games for the Padres, Phillies, and Tigers from 1995 through 1997.

In November 1994, the Padres named Spinks pitching coach for Idaho Falls of the Rookie classification Pioneer League. He spent the 1995 season there and then moved on to the Clinton Lumber Kings in the Midwest League (Class A) for 1996. His prize pupil was Matt Clement.

After those three years, Spinks became a free agent scout. He noted, “I have 16 teams that I’m responsible for, in eight different organizations, in the Texas League and the PCL.” One of his favorite tales from the road was about how he beat a speeding ticket thanks to his radar gun. The traffic cop was using a JUGS gun, but Scipio’s model showed both the JUGS and SRA systems — with a gap between the two readings. He convinced the officer: “See, I wasn’t going 65. I was only going 60.”

“Oh, OK. Have a nice day.” Spinks laughs uproariously every time he tells the story.27

Spinks lives in the suburban Houston area with his third wife, Jeanette Quinn, whom he married in 1979. He is also involved with youth baseball around Houston. For example, in 2002 he took an Astros team to Australia as part of the US contingent in the Goodwill Series for youngsters aged 13 to 18. 28 He also offers some optimism about a baseball trend that has received much attention in recent years. “There are African-Americans playing baseball more but not as many as in years past. Football and basketball have been glorified by TV, but guys like Torii Hunter and Barry Larkin are really trying to get black kids playing more baseball. I work with young pitchers in the Houston area and I have seen more and more young black kids playing baseball.”

Scipio’s advice to all young players is how he approached the game himself: “Play hard, practice hard, and have fun.”

Last revised: January 20, 2010

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Scipio Spinks for his memories (via e-mail). Thanks also to SABR member Alfonso Tusa (Venezuelan statistics) and Jorge Colón Delgado (Puerto Rican statistics).

Sources

Russo, Neal. “Cards Boast a Conqueror in Scipio.” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972: 20.

Eisenbath, Mike. The Cardinals Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999: 287-88.

www.thebaseballcube.org

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

www.retrosheet.org

SABR Minor League Database

SABR Baseball Encyclopedia

www.northernleague.com

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Notes

1 Green, Hurley. “Pride in Two Areas.” South Side Bulletin, February 7, 1968: 1.

2 Dozer, Richard. “Reuschel sharp, but A’s top Cubs.” Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1974: E4.

3 “Jackson Park Pitcher Signs with Major’s Astros”. Woodlawn Booster, Chicago, July 6, 1966: 4.

4 Ibid.

5 SABR member David Trombley’s online history of the Northern League: http://www.usfamily.net/web/trombleyd/Northern%20Highlights53-71.htm#1966.

6 Forrest, Leon R. “On Baseball, Acting, And Long Journeys.” Woodlawn Booster, October 4, 1966: 1.

7 “Potent Stars Quieted by Astro Hurler.” Record-Chronicle, Denton, Texas, August 4, 1967: 11.

8 “Spinks Throws A No-Hitter, Gets Beaten.” Evening News, Ada, Oklahima, May 9, 1969: 7.

9 Weiskopf, Herman. “Highlight.” Sports Illustrated, September 29, 1969.

10 Neyer, Rob. Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006: 170.

11 Vass, George. “The Magic Men of the Mets.” Baseball Digest, August 1972: 21.

12 Mizell, Hubert. “Scipio Spinks — humorist with talent.” Associated Press, March 9, 1973.

13 Anderson, Dave. “The Cardinal and ‘Mighty Joe Young.’ ” New York Times, June 24, 1972: 23.

14 “Five Cardinals sign contracts for 1974.” The Telegraph, Alton, Illinois, January 5, 1974: B1.

15 Chass, Murray. “Mets Lose Two to Cards, Fall 3 Behind; 7-1, 2-1 Setbacks — Spinks Fans 13 in Opener.” New York Times, June 26, 1972: 43.

16 “Five Cardinals sign contracts for 1974.”

17 “Will shaved head bring him luck?” Associated Press, July 3, 1973. Fuller text accompanies photo in Journal-News (Hamilton, Ohio).

18 Giordano, Paul. “Trade talk spreads among Phils, Cards.” Bucks County Courier Times, March 20, 1974: 41.

19 Scoggins, Charles. “Sox snap losing streak.” The Sun, Lowell, Massachusetts, May 19, 1975: 16.

20 Bryson, Bill. “Sparks says Spinks must be sharper.” Des Moines Register, April 7, 1975.

21 “Bears move into second place in American Assn.” Daily Tribune, Greeley, Colorado, July 11, 1974: 40.

22 Hennick, Tom. “West Haven Yanks Looking Up.” Daily News, Naugatuck, Connecticut, June 20, 175: 10.

23 “Ott won’t forget first Pirate start.” Valley Independent (Monessen, Pennsylvania), September 24, 1976: 9.

Full Name

Scipio Ronald Spinks

Born

July 12, 1947 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.