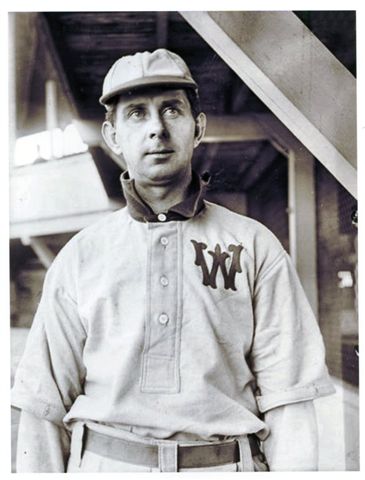

Scoops Carey

George Carey, who skipped around professional baseball like a well-thrown rock across a pond, spent four seasons in the major leagues during his professional baseball tenure. Traversing the country from Minneapolis to Memphis in the minor leagues, Carey bracketed his career from 1892 to 1911 — the inauguration years for basketball and the Indianapolis 500, respectively. Towards the end of his career, Carey found himself recounting his playing days for a reporter from the Daily Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock, where he played for the Travelers in the Southern Association in 1909.

George Carey, who skipped around professional baseball like a well-thrown rock across a pond, spent four seasons in the major leagues during his professional baseball tenure. Traversing the country from Minneapolis to Memphis in the minor leagues, Carey bracketed his career from 1892 to 1911 — the inauguration years for basketball and the Indianapolis 500, respectively. Towards the end of his career, Carey found himself recounting his playing days for a reporter from the Daily Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock, where he played for the Travelers in the Southern Association in 1909.

Dubbed “Scoops” for his defensive prowess at first base, Carey broke down the intricacies of maintaining the field, protecting the bag, and navigating the obstacle that frustrated him:

How do I get those low throws? Well, for one thing, I always see to it that the ground around first base is well wet down. Then you can pretty nearly tell how a low-thrown ball is going to bound. If the ground is dry and hard, it is likely to shoot off at some unexpected angle. After all, those low throws aren’t the hardest to get. Almost invariably they come from clear across the diamond, so that you have lots of time to gauge the ball before it gets to you. Then it’s only a question of getting your mitt on the ball. The throws that I dread are the ones from the second baseman when he has to hurry his peg to get the runner. In his hurry, he doesn’t have time to take aim and you never know where the bail is coming, and the distance that it travels is so short that the ball is right upon you before you see it. A first baseman is pretty lucky when he gets that sort. And after all, after all [sic], there’s a whole lot of luck to this old baseball game. The longer I play it, the more I realize that. 1

The fourth of nine children born to Samuel and Sarah (Drummond) Carey in Pittsburgh, George Carey came into the world on December 4, 1870. Tragedy visited the Carey household often — Aged from infancy to either 19 or 20 years old, two brothers and two sisters died from various causes. George’s parents settled in East Liverpool, OH, in 1874; his first dose of formalized baseball came in the early 1890s with the semi-pro East Liverpool Eclipse, which was “as strong as any minor league team to be found in the country” boasted the city’s Evening Review newspaper in 1910. The Eclipse merged with East Liverpool’s Crockery City Club in 1891.2

Carey was at the heart of a near-riot during his Eclipse days, though he was the initial victim, not the aggressor. On September 25, 1891, Carey and the East Liverpool Eclipse took on the Wooster team for a $100 reward. Bashing an eighth inning hit that had the makings of a home run if he could get around the bases, Carey avoided the attempt of the Wooster first baseman to “trip” him. When an Eclipse coach “grabbed [the first baseman] by the throat,” pandemonium erupted. Hundreds of the estimated 2,000 fans piled onto the field. The police restored order so the game could conintue. It ended in a 6-6 tie. A week later, Carey crushed “one of the longest hits recorded at West End Park” in a 13-6 defeat of Tarentum.3

Various sources attribute Carey as attending West Virginia University, but no alumni records mention him nor does his name appear on any student enrollment lists between 1885-95.

Carey began playing professional baseball for the Altoona Mountaineers in the Pennsylvania State League at 21 years old. He hit .261 across 59 games in 1892; he exploded in his sophomore year for Altoona, batting .367 with nearly double the playing time, 97 games.. In 1894, he left a city created by the Pennsylvania Railroad for a larger one built on beer, the Milwaukee Brewers of the Western League. He continued consistently clobbering the ball and ended the season with a .365 batting average and 206 hits in 127 games. 4

Before the 1895 season, Carey married Minnie Webster, a hometown girl. George Travis, Carey’s manager with the Eclipse, performed the ceremony, Thursday, March 7 at the Third Street house of Carey’s mother. There was no time for a honeymoon; East Liverpool’s Evening News Review reported that Carey would head to Macon, GA on Saturday to join the Baltimore Orioles, the returning National League champions, in spring training.5

Playing with this squad from the port city on Chesapeake Bay must have been a heady experience for the young rookie. Managed by Ned Hanlon, and featuring a whole slew of future Hall of Famers — Wilbert Robinson, Hughie Jennings, John McGraw, first baseman Dan Brouthers, outfielder Willie Keeler, and second baseman Kid Gleason, who would later suffer the indignity of managing the 1919 Black Sox — the Baltimore club had gone 89-39 the previous season to capture the NL flag.

Spring Training started on a hopeful note — or at least a healthy one. Carey and his cohorts, including Gleason, Bill Kissinger, and Jack Horner, were described as being in “perfect condition.” (Horner did not make the 1895 regular season squad.) A trip to Danville, Virginia showed the team’s honor, even if the opponents were beyond subpar.6 The Baltimore Sun noticed Carey’s versatility, even if somewhat guardedly:

“Carey is a tip-top ballplayer and will be a valuable man for the club. He can fill any position creditably except that of pitcher, and he is a reliable batter and a fast runner. But he is a new man in the League and probably requires seasoning. Besides, he is exposed to the dangers which beset all young players when they get into fast company. One of these dangers is that he may be overcome by nervousness, and thus be prevented from doing his best work, and another is that, having succeeded, he may be seized with that too-prevalent malady, ‘swelled head.’ These two things Carey has to guard against, and, being a sensible youth, he will probably escape them both.”7

Designated for the Orioles bench at the beginning of the season, Carey soon won a starting position, bumping Dan Brouthers, nearing the end of his Hall of Fame career, from the lineup. Carey played in 123 games, but his batting performance was not immediately satisfying to Hanlon, who moved the first baseman from batting clean-up to seventh in the order. It became clear almost immediately “that he would hit well below the team average,” explains baseball historian David Nemec. “In addition to a long, looping swing that produced a plethora of lazy fly balls, Carey was agonizingly slow, swiping just two bases for a team built on speed.” 8

Dependability was Carey’s trademark, prompting the Sun to compliment Baltimore’s newcomer throughout the season. For example, on August 22nd, Carey received this accolade: “constantly going up in the air or digging down in the ground after wide throws by the other infielders, and he never failed to come up smiling with the ball.”9

Carey’s potential value to other teams attracted attention from the baseball scribes. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat speculated that Carey might add great value to the hometown Browns, but, alas, he was unavailable. An emotional boost happened in early May, when 200 friends from East Liverpool showed up at a 9-2 victory against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Though he went hitless that day, he recorded 11 outs in the field.10

Carey and Brouthers were on opposite sides for the first time when the Orioles faced the Louisville Colonels on May 21. Carey banged out two hits in Baltimore’s 8-7 victory. By late May, the Sun predicted that replacing Brouthers with Carey would lead to Hanlon being “fully vindicated before many weeks pass.” Though noted more for fielding than batting, Carey’s swings occasionally caused impressive output. In a 12-5 rout of Louisville, Carey got two hits and turned two “brilliant” plays afield, including a ball off Brouthers’s bat and a “low, hard throw.” On a rare day of hitting power, Carey had a home run, a double, and a single in a 15-5 victory against Boston on August 1. Two weeks later against Boston, he got three-quarters of a circuit-hitting performance: single, double, and triple. He went 4-for-5 against Connie Mack’s Pittsburgh Pirates in late August and repeated the feat about a month later against the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. Though hardly a feared batsman — only a single home run in 299 major league games — Carey improved his prospects by using a lighter bat.11

A twisted ankle in a 13-3 lashing of the Washington Senators on July 1 forced Carey to miss five games. He returned to the lineup on July 7 against St. Louis, notching one hit. A fielding controversy faced Carey in mid-July when Oliver Tebeau of the Cleveland Spiders claimed that his glove size exceeded normalcy for a first baseman. The umpires measured and agreed. Cleveland won 1-0. During these dog days, Hanlon squashed a rumor about trading Carey and cash to Boston for Tommy Tucker.12

From 1894-97, the National League held the Temple Cup series, a best-of-seven battle between the first and second place teams. Baltimore appeared in all four Temple Cup championship series, losing the first two to the Giants and the next to the Cleveland Spiders when Carey was with the team. Baltimore won the next two series against Cleveland in 1896 and the Boston Beaneaters the following year.

In the Daily Arkansas Gazette piece, Carey recalled his glory days with the Baltimore squad: “There was the brainiest lot of ball players ever gotten together on one team. They didn’t need any manager except to look after the business affairs of the team. Every one of them knew more baseball than Ned Hanlon. You notice that he failed to make good as a manager after he left the old crowd, don’t you?”13

There was also a mission of considerable importance for the Orioles — make life “miserable” for umpires: “They were after the umps all the time and whenever a close decision went against them, there was sure to be trouble. It got them something, too. All the umpires were afraid of the bunch. I remember in one of the games that we played against Cleveland, Bob Emslie called a strike on me that was clearly wide. I started to make a kick. If you say another word I’ll fine you and put you out of the game. There are enough crabs on this team without you youngsters.”14

Carey spent most of the rest of his career in the minor leagues and never again matched the excitement of being on a championship team. In 1896, he played for the Syracuse Stars in the Class A Eastern League. His nickname shifted to “Scoop ‘em Up” in the press. He split the 1897 season between stints with the Philadelphia Athletics and the Reading Actives, both in the Class B Atlantic League.15

Carey returned to the major leagues in 1898, suiting up for the NL Louisville Colonels. He didn’t get much playing time there: eight games, 33 ABs, and an average below the Mendoza line. The Class A Minneapolis Millers in the Western League gave him far more opportunities that year: 107 games, .252 batting average; he played for them again in 1899. Returning East, Carey found his stride with the Buffalo Bisons in 1900 and 1901, playing in 135 and 134 games and hitting .271 and .316, respectively.

In 1902, Carey made his third voyage to the major leagues, joining the Washington Senators in the second year of the American League, which had begun operating the previous year. The veteran Carey impressed the Washington Post in early spring: “Of course, ‘Scoops’ Carey looks the best of the bunch,” observed its correspondent, “having been here during all the good weather of the past two weeks. The stiffened joints and muscles of the first two or three days after he opened negotiations with the family physician have all disappeared with the fat and perspiration he has worked off, and he is way to the good.”16

Carey’s return to the majors was tentative, though. Had a legal snag been enforcd, it might have removed him from the Washington lineup because he had signed a agreement drafted by his own lawyer mandating a three-year term of service with the Bisons. Buffalo’s manager George Stallings contemplated lobbying AL President Ban Johnson to order Carey returned to western New York, but nothing came of it. 17

Carey, just a shade over 30 years old, began the season with a miserable .188 batting average after 10 games, but a perfect fielding record — no errors in 111 chances (105 putouts, six assists). Post readers found unfriendly verbage describing the new Washingtonian: “‘Scoops’ Carey had an hour to make first on his hit to short right,” groused the Post, “but it takes more time than that for ‘Scoops’ to cover that distance and he was out.”18

Carey regained their trust a few weeks into the season:

When one considers the difficulties that beset a first baseman, the work of ‘Scoops’ Carey at first base compels nothing short of admiration. ‘Scoops’ has played a perfect game at that corner since the season opened. His marvelous one-hand stops and catches, the time he saves on close plays by doing that great ‘split’ of his, excite the praise of all. His work stamps him as the best first baseman in the game to-day. His only weakness in the game is his failure to hit with any degree of consistency. For the first two weeks the long fellow failed to land safely, although he was spanking the ball hard all the time, but he was unfortunate enough to have some fielder close to the place to which the ball went. Last week he did better, and hit for four singles, a pair of doubles, and a triple.”19

By May 18, Carey’s average had climbed to .272. In 222 fielding chances (207 putouts and 15 assists), his defense remained flawless. The following week, his average climbed above .300, and by June 1, the once-struggling Carey sported a .328 batting average. At the end of the month, he had made his second error. The Post disputed his third error, claiming that Orioles infielder Harry Howell gave Carey an “awful bump” instead of just stepping on first base in a 4-3 victory for Washington. A few weeks later, a broken hand sidelined Carey for a number of games. He also suffered a broken nose in June. Nonetheless he turned in a stellar year: .314/.440/.790 plus a .989 fielding percentage (14 errors in 1,273 chances) — and a 2.3 WAR.20

Carey was known for his generosity, even when the requests were not bona fide. One tale involves his being approached after a game by a guy claiming to have seen him play in Johnstown. Carey had a lengthy conversation with this reconnected “acquaintance,” gracefully accepting compliments about his ability. But then came a request for $1. “I had seen it coming too late,” explained Carey. “It was another dollar gone to glory. I wish I had an itemized statement of the money I have given on touches of this kind. If I had it back I’d be a magnate and not a player, you can bet your life.”21

The following season, Carey’s fortunes plummeted. After 48 games and a .202 batting average, the Senators traded Carey in early August, 1903, to the single-A Southern Association’s Nashville Volunteers for Hugh Hill, a pitcher-turned-outfielder. Apparently, there had been other major league suitors, including the St. Louis Cardinals and the Philadelphia Phillies. Carey played 14 games for Nashville and batted .286. He also played 24 games and batted .256 for the single-A Eastern League’s Buffalo Bisons.22

The following year Carey went to Kodak country, becoming a regular for the Rochester Bronchos in the Class A Eastern League. 1904 was a solid season: 134 games and .275 batting average. Carey had a fearsome Opening Day, his best ever, going 5-for-5 in a 6-5 loss to the Jersey City Skeeters. By mid-season, Carey had found his way into the hearts of Rochester’s baseball fans. “What would happen to Rochester with Scoops Carey left out is too awful to contemplate,” exclaimed the Buffalo Evening News. “He has won all the games the Bronchos have on their slim victory list.”23

During the off-season, Carey tried to help younger players in East Liverpool find job openings in baseball. Any thoughts he might have entertained about settling in Rochester during the 1905 season dissipated 43 games into the season, when Carey found himself with the Grand Rapids Orphans, a team in the Class B Central League. He became a beloved ballplayer there, too. The Evening Review kept his hometown fans abreast of their famous resident’s latest exploits Quoting the Grand Rapids Evening Press about a game against the Dayton Veterans, the newspaper showed that Carey, after 13 years, hadn’t lost his touch:

the star performer of the day, with a home run over the left field fence, a two-bagger that sent in a run, and a catch that will never be forgotten by those who were awake enough to see it. It was on a low, wild throw back of first, the long fellow stretched out, shifted feet on the bag and pulled the ball safely off the ground for the out at a time when the bets were beginning to look dangerous. ‘Scoops’ Carey is the idol of the fans these days, and they feel safe any time the ball is hit in his direction.

Described as a “quiet, business-like player,” the Grand Rapids sports writers conveyed what Carey’s townsfolk already knew: their favorite son knew how to make “a warm place for himself in the hearts of the local fans.”24 Carey played 89 games for Grand Rapids, then headed back to Tennessee, where he played three seasons for the Memphis Egyptians in the Southern League. Carey’s prodigious defensive skills garnered praise once again. The Memphis Tennessean lauded his “wonderful spears of wide tosses and scoops of underground throws” at his position.25

The three seasons with Memphis were the most consecutive years Carey had spent with any one ball club in his career. Finally, at age 38 and the start of the 1909 season, it appeared that he might have found himself a baseball home.“I have about decided never to quit the game,” said Carey. “I can still lob ‘em around and . . . am in the pink of condition.” He thought that his manager [Charlie Babb] was “one of the best . . . in the business” and the club’s president “one of the best fellows in the world.” ”26

The club didn’t reciprocate his feelings, unfortunately; Memphis handed Carey his walking papers in June. A couple of weeks later, he signed with the Little Rock Travelers. Bought by the Fort Wayne Billikens in the Class A Central League after the 1909 season, Carey got sold to the Altoona Rams in the Class B Tri-State League. Later, he found a managerial opportunity back in Arkansas with the Blytheville Boosters ball club.

The career minor-leaguer was just about done. He tried his hand at managing in 1910 season, bringing home a pennant for the Jonesboro Zebras in the Class D Northwest Arkansas League

The following season, the 40-year-old Carey appeared in 58 games for the Greenwood [MS] Scouts of the Cotton States League, hit .158, and hung ‘em up. His playing days were finally over. It was reported that Carey and teammate Orth Collins, would be Memphis policemen in the winter.27

A few years later, after conversion at a Billy Sunday revival in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, Carey became active in the burgeoning temperance movement; he joined an Anti-Saloon League and served as one of its delegates in a meeting in Columbus, OH, in 1915. Earning his living as a painter, Carey made religion the cornerstone of his life.28

Still a young man aged 46, Carey died in East Liverpool City Hospital on December 17, 1916, of heart frailties — specifically mitral regurgitation and stenosis, plus chronic arteriosclerosis. Several newspapers, including the Pittsburgh Press, specifically mentioned that his religious devotion “was known to almost every person in East Liverpool.”.29

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 “‘Scoops’ Carey Reveals Some of the Secrets of His Craft,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, July 25, 1909.

2https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/76250666/person/42374428427/facts. “Samuel W. Carey, Aged Resident of City, is Called,” East Liverpool OH Morning News, , January 22, 1914; “Carey Has Led First Basemen During Past Eighteen Years,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening Review, March 26, 1910; “The O&P Baseball League and other Baseball History in Early ELO, East Liverpool Historical Society, http://www.eastliverpoolhistoricalsociety.org/OPbaseball.htm. Accessed April 24, 2018.

3 “Riot Almost Occurred In Famous Eclipse-Wooster Game At The West End Park 25 Years Ago,” & “Eclipse Beat Tarentum In Game Played At West End Park 25 Years Ago,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening Review, January 25, March 26,1915.

4 Jane Metters LaBarbara to author, February 26, 2018; Catherine Rakowski to author, February 28, 2018; in author’s possession,.

5 “George Carey Married,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening News Review, March 8, 1895. The newspaper shows the bride’s maiden name as Webster, but Ancestry.com shows Weston. Travis was an attorney, described “an old baseball chum of the groom.”

6 Against the “Danville Club” before the season, Carey, who hit .261 in 1895, showed a rare display of power; he hit two triples in the contest held in Danville, VA. Upon further scrutiny, this achievement fades. Danville’s team makeup had been misconstrued — it had four players, the Sun described as “mere boys and further proved to be tenth-rate amateurs. Three . . . failed miserably” in the outfield, “and the fourth stood in the position usually occupied by a shortstop.” These were the only players Danville fielded; the Orioles — including first baseman Carey — filled in the rest of the positions. It was a bait-and-switch at the expense of time, money, and physical energy for the champions looking for competition to warm them up before the regular season. There was no reason to play the game, other than staying true to an agreement violated by Danville’s lack of good faith. It was a miserable afternoon on a field bearing no description, before a crowd of about 100. Everybody was “completely disgusted,” both the spectators who had expected to see their hometown team, and, of course the NL champions. “Baltimores Working Hard,” & “The Baltimores Disgusted,” Baltimore Sun, April 1, 5, 1895

7 “Come, Come, Get At ‘Em!,” Baltimore Sun, April 13, 1895.

8 “The Baltimores Move On,” Baltimore Sun, April 9, 1895; David Nemec, ed., Major League Baesball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1, The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011) 296.

9 “Another From Anson,” Baltimore Sun, August 22, 1895. See also Sun issues of April 27, June 3, 12, 20, August 3, 6, 23, 31, September 10, 26, 1895.

10 “Diamond Flashes,” & “Pittsburg The Victim,” Baltimore Sun, May 7, 10.

11 Ibid., “Baltimores Win A Game,” “Baltimores At Practice,” “Boston Routed,” “Another From Boston,” “Base-Ball,” “The Champions Won,” “Scared Orioles,” and “Diamond Flashes,” Baltimore Sun, May 22, 25, 29, August 2, 15, 28, 29, September 20.

12 “Some Things Come Easy,” “Baltimores Go Away,” “Hemming’s Miserable Work,” “Two Bad Defeats,” & “Diamond Flashes,” Baltimore Sun, July 2, 3, 8, 17, August 21. .

13 See note 1.

14 Ibid.

15 “Base Ball Notes,” Wilkes-Barre Times, August 5, 1896.

16 “Day of Hard Practice,” Washington Post, April 4, 1902.

17 “Baseball Notes,” Washington Post, April 30.

18 “Defeat Ended Series,” Washington Post, May 2.

19 “Washington Is Sixth,” Washington Post, May 12.

20 “Slow Base Runners,” “League Race Is Close,” “First Month Of Play,” “Errors For Senators,” “Beaten In Loose Game,” “Not A Senator Scored,” & “Del[a]hanty’s Hit Won,” Washington Post, May 19, 26, June 2, 26, 30, July 12, August 6. Carey’s success prompted aspiring players, including John Godwin, another East Liverpoolian, and Harry Barker, to seek advice. Godwin played in the minor leagues in 1898 and 1903-12. He got some major league experience with the Boston Americans in 1905 (15 games) and 1906 (66 games). Barker never made it out of the minors from 1902 to 1908. Washington Post, May 10, 1903.

21 “Baseball Pennants,” Washington Post, June 21.

22 “Loftus Gets New Player,” and “Baseball Gossip,”, Washington Post, August 4, 9. Carey batted .286 in 14 games for Nashville.

23 “11-Inning Games,” Buffalo Courier, April 30, 1904; “Right Off The Bat,” Buffalo Evening News, June 29, 1904.

24 Ibid. “Helping Young Players,” “Scoops Carey Is Winning New Laurels,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening Review, January 28, July 22, 1905.

25 “New Stand For Memphis Fans,” [Memphis] Tennessean, January 28, 1907.

26 “‘Scoops’ Carey Touts Bill Powell After Deciding To Always Play Base Ball,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening Review, April 10, 1909.

27 “Baseball Notes,” Williamsport Sun-Gazette, October 10, 1911 “‘Scoops’ Carey To Be Released,”, June 2, 1909; “‘Scoops’ Carey to Manage Blytheville,” Arkansas Democrat, May 25, 1910; “Meridian’s Stretch Drive Breaks Tie,” [New Orleans, LA] Times-Democrat, June 14, 1911. Oddly enough, given the contingencies of Class D baseball near the turn of the 20th Century, Carey (maybe because he was the oldest guy on either team) went behind the plate to call balls and strikes in a game between the Scouts and the Meridian [MS] White Ribbons. See “Baseball Notes,” Williamsport Sun-Gazette, October 10, 1911.

28 “‘Scoops’ Carey Makes Visit,” [East Liverpool, OH] Evening Review, February 6, 1915; “Scoops Carey Dead; Once Baseball Star,” [Elmira, NY] Star-Gazette , December 19, 1916; “Scoops Carey — Not Max — A Temperance Worker,” Pittsburgh Press, March 25, 1916.

29 George Carey Birth Certificate, https://ancstry.me/2GQlhdV; “Scoops Carey, Old Baltimore Star, Is Dead,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 18, 1916.

Full Name

George C. Carey

Born

December 4, 1870 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

December 17, 1916 at East Liverpool, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.