Montreal Royals team ownership history

This article was written by Steve Rennie

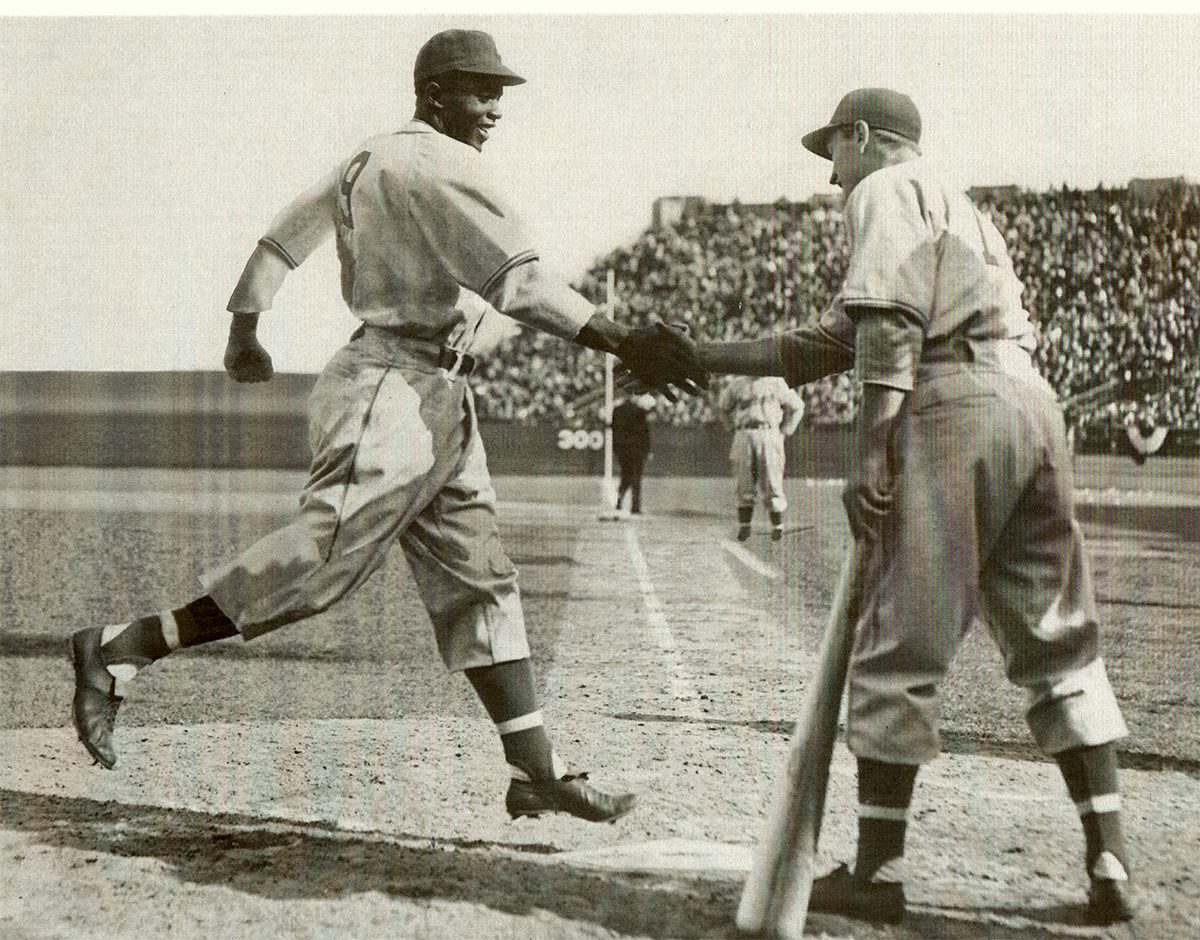

George Shuba of the Montreal Royals greets teammate Jackie Robinson at home plate on April 18, 1946. (Courtesy of Greg Gulas, Carrie Anderson, Mike Shuba)

Tears welled in Jackie Robinson’s eyes as he was hoisted onto the shoulders of adoring fans, their chants reverberating off the walls of Delorimier Stadium. It was a moment of triumph, a culmination of resilience and talent, as Robinson, the legendary second baseman for the Montreal Royals, basked in the glory of victory in the 1946 Junior World Series.

Despite a challenging start to the series, Robinson had proven his mettle, both on and off the field. His performance spoke volumes, silencing doubters and winning over hearts. Even manager Clay Hopper, a Mississippi native who initially harbored reservations about Robinson joining the Royals, extended his admiration, recognizing Robinson not only as a remarkable ballplayer but also as a gentleman.1

The scene was electric, with faithful Royals fans refusing to depart the ballpark, their fervor reaching a crescendo as they clamored for a glimpse of their hero. Robinson, overwhelmed by the outpouring of support, found himself surrounded by a sea of admirers, their affection palpable as they lifted him high into the air, chanting praises in French and English alike.2

Reflecting on the momentous occasion, Robinson recounted the overwhelming swell of emotion and the indomitable spirit of the crowd. His departure from the ballpark was akin to a hero’s journey, with fans trailing him to the very end, all the way to the train station, their unwavering support a testament to the profound impact he had made.3

As Robinson bade farewell to Montreal, his legacy reverberated throughout the city, leaving an enduring imprint on its history. Yet, as the years passed and the Royals’ fortunes dwindled, the echoes of that triumphant era began to fade, marking the end of an era for professional baseball in Montreal.

***

As the excitement surrounding Jackie Robinson’s single season in Montreal waned, the legacy of the Montreal Royals continued to resonate within the city. Their role in breaking baseball’s color barrier endured as a defining moment in the sport’s history long after the team’s departure in 1960. When Robinson donned their uniform in the spring of 1946, he became the first African American to play in a major professional White league for decades, marking a watershed moment not only for the Royals but for baseball as a whole.

Yet, Robinson was not the sole luminary to grace the Montreal Royals roster. Future legends like Don Drysdale, Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, and Roberto Clemente all passed through Montreal on their path to stardom, leaving an indelible mark on the team’s storied legacy.

Although the Royals have long since departed, their memories linger in the hearts of many Montrealers, serving as a testament to the lasting impact of their contributions to the sport.

Baseball’s roots in Montreal trace back to the mid-nineteenth century, when enthusiasts began forming clubs and organizing games. However, in the 1860s, the city banned baseball in its parks, fearful an errant ball could put those who were not playing at risk. That gave rise to around 40 baseball clubs in Montreal between 1867 and 1887. Men gathered at athletic clubs around the city to play, yet only a handful of these early teams endured beyond a few years. Despite the transient nature of those early clubs, their existence laid the groundwork for Montreal’s enduring passion for the sport.4

During the summer of 1890, Montreal emerged as a possible relocation destination for the International League’s struggling Buffalo Bisons franchise. In June 1890, Charles D. White, the owner of the Bisons, embarked on a 400-mile journey to Montreal to explore potential sites. He settled on the Shamrock Lacrosse Grounds at the intersection of Saint-Catherine Street and Atwater Avenue. This location, familiar to hockey fans, was situated across the street from what would later be the site of the Montreal Forum, which opened in 1924.5

The club lasted only nine games, losing five of its their six games in June. They drew a crowd of 2,000 fans to their first game in Montreal, against Toronto, which they lost 11-10, and after that attendance was sparse. Montrealers’ seeming lack of interest in professional baseball prompted the International League to move the club to Grand Rapids, Michigan. Montreal quickly got another chance when the International League’s bankrupt Hamilton, Ontario, franchise was transferred to Montreal. This club did not fare much better than its predecessor, winning only three of its nine games and drawing a paltry number of spectators to the Shamrock Grounds. The International League folded in July 1890, once again leaving Montreal without professional baseball. Many Montrealers longed for a new pro team to call their own, not a failing franchise from elsewhere hoping to turn things around up north.6

They got their wish a few years later. American railway worker Joe Page teamed with Canada’s first major-league baseball star, James Edward “Tip” O’Neill, to bring professional baseball back to Montreal in the mid-1890s using the nickname Royals. O’Neill eventually left the club, leaving Page to take charge on his own. Undeterred, Page partnered with New England sports promoter William H. Rowe, orchestrating a series of highly successful exhibition games throughout the summer of 1896 that led to a turnaround in the club’s fortunes. Buoyed by their success, Page and Rowe set their sights on extending their tour beyond Quebec and New York State, venturing into Ontario and the Eastern United States in 1897.7

In June of 1897, an opportunity arose for Montreal to reenter the Eastern League fold. The faltering Wilkes-Barre franchise emerged as a prime candidate for relocation, and Montreal was once again mentioned as a possible destination. Rowe swiftly suspended the touring Montreal team’s season and dedicated himself to securing the necessary funds to bid for the Wilkes-Barre franchise. He rallied support from affluent investors to bolster the endeavor. However, Rowe’s plans took an unexpected turn when another opportunity for relocation presented itself. After a devastating fire that destroyed the ballpark in Rochester, New York, the club found itself in need of a new home to finish out the season. Rowe tirelessly lobbied Eastern League President Pat Powers, who harbored doubts about reinstating a team in Montreal. Powers also believed the city was too far from the league’s other franchises, making it an impractical choice. Nonetheless, Rowe’s persistence paid off and on July 16, 1897, the Rochester Jingoes franchise moved north to Montreal. During that period, Atwater Park, bordering the wealthy enclave of the city of Westmount, stood out as the only park equipped with a grandstand large enough to accommodate a big crowd. Atwater Park hosted the club’s Saturday games. Due to sports restrictions on Sundays in the city of Westmount, Sunday games took place at either the Shamrock Grounds or the National Club Grounds. Attendance at these Sunday games often surpassed that of the Saturday matches.8

The team finished in seventh place, often playing before sparse crowds. No one knew what to call the team, with monikers like the Snowbirds, Canuck Juniors, the Frenchmen, and the Eskimos bandied about. Another nickname emerged, one that would later become synonymous with baseball in the city: the Royals. The Montreal Gazette first referred to the club by this nickname. In 1897 Canada and the other British Commonwealth nations were celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria to mark the monarch’s 60th anniversary on the throne. A newspaper in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, suggested the nickname to mark the milestone. “The Wilkes-Barre Record baptized us,” wrote the Gazette on July 28, 1897. “In the future, we will call ourselves the Royals. It seems very appropriate in this jubilee year.” Most people, however, simply called them the Montreals or the Montreal Baseball Club. Bolstered by Cameron’s investment in the ballpark, the club returned to the Eastern League the following season, stunning many by clinching the pennant that year.9

It was the last time the Montreal club would taste such success, as it faced struggles in the seasons that followed.

In 1902, American League President Ban Johnson had his sights set on a team to begin play in New York City the following season. He jettisoned the Baltimore Orioles in favour of the New York Highlanders (later known as the Yankees). Baltimore, suddenly with nowhere to play in 1903, sought refuge in the Eastern League. Two franchises, both struggling, were candidates to be dropped to make room for the Orioles: Rochester and Montreal. Eastern League owners had long grumbled about the expensive overnight trips to Montreal, so it came as no shock when league President Powers announced that the city would lose its franchise. What no doubt stung Montrealers was word that popular player-manager Handsome Charlie Dooley had secretly invested in the Orioles.10

Montreal’s absence from the Eastern League was short-lived. P.H. Hurley, the owner of the Worcester, Massachusetts, team, relocated his struggling franchise to Montreal midway through the 1903 season. A year later, Hurley sold the team to John Kreitner, a Buffalo entrepreneur. After the 1905 season, Kreitner sold the team to a New York group led by Frank Farrell, a part-owner of the American League’s New York Highlanders. Despite the team changing ownership multiple times during this period, one aspect that began to solidify was the team’s nickname. Montrealers largely embraced the name Royals, or Les Royaux in French. They were less enthusiastic about Farrell running the team out of New York. So in January 1908, Farrell dispatched George Stallings to Montreal to find a local buyer for the club. Stallings brokered a $10,000 (Canadian) deal with three Montreal business owners to buy the Royals: minority owners E.R. Carrington, who managed the Thiel Detective Service; Montreal Brewing Company executive Hubert Cushing; and majority owner Sam Lichtenhein, a local sports promoter who owned the Montreal Wanderers hockey team and would become the baseball club’s president.11

The trio would run the club for nearly a decade. Over that period, they undertook two stadium rebuilds and underwent five manager changes. Relations within the ownership group were occasionally strained. At one point, Carrington and Cushing, unhappy with manager Eddie McCafferty’s performance, pushed Lichtenhein to fire him. Lichtenhein refused and offered instead to sell his share in the team to them for $50,000 (Canadian). They declined.12

Despite many players joining the battle overseas, Eastern League owners decided to continue playing throughout the First World War. Lichtenhein reluctantly agreed to field a team again in 1918, stating, “We don’t believe in operating the league under existing conditions for the benefit of a couple of clubs who will make money.” He never got the chance. The league opted to replace its franchises in Montreal, Providence, and Richmond with new clubs in Birmingham, Syracuse, and Jersey City. Professional baseball was one again no more in Montreal. It would remain that way for the next decade.13

DeLorimier Park, circa 1933 (Musée McCord Museum)

George Stallings wanted to bring a team back to Montreal. But this time he didn’t want to be the middleman; he wanted to be an owner. So in 1927 Stallings returned to Montreal looking for local investors who could sit on the board of the newly formed Montreal Exhibition Company Ltd., including well-connected Montreal lawyer and politician Louis Athanase David, financier Hartland MacDougall, and local investment dealer Ernest J. Savard of the brokerage firm Savard and Hart. (In 1935 Savard was part of an investor group that purchased the Montreal Canadiens). Stallings brought in his associates, Carlos Ferrar and Walter E. Hapgood, to run the club’s day-to-day operations. They paid the owners of the International League’s struggling Jersey City Skeeters franchise $225,000 to move the team to Montreal and rename them the Royals for the 1928 season. (It is unclear if they paid in Canadian or American dollars.) All that was missing was a ballpark. The new owners ruled out a return to Atwater Park, feeling the venue was too small. They purchased property in the city’s east end at the corner of Delorimier and Ontario Streets and began construction in the dead of winter on a new ballpark. Various reports have estimated the cost of the project to be anywhere between $700,000 and $1.5 million (Canadian), although it was likely closer to the lower end of that scale, as the city assessed the combined land and building value to be $703,550 in 1928.14

Stallings took on the role of the Royals’ manager, guiding them to a victorious start in their first game of the season and keeping them in contention for the pennant through June. That first season was also a box-office success. The club made $40,000 from season-ticket sales in 1928. The club also earned substantial sums from concessions and selling advertising space on the fences and scoreboard. Amid the team’s early success under Stallings, tragedy struck when a heart attack during a road trip in Toronto prevented his return to managerial duties. Stallings died a year later at the age of 61.15

The stock market crash of 1929 took its toll on the new Montreal franchise over the next few years. The club’s lacklustre play didn’t help matters. Fan support began to dwindle, and ownership realized they needed to improve the on-field product if they wanted to fill the stands. To help in that regard, the Royals hired Frank J. “Shag” Shaughnessy as the club’s general manager. Born in Illinois, Shaughnessy had a successful playing career in both baseball and football before transitioning to coaching and management. He arrived in Montreal in 1912 to lead McGill University’s football team, a position he held for 17 seasons. During the football offseason, Shaughnessy remained involved in baseball by managing semipro teams. He also scouted for the Detroit Tigers, and he was in the crowd when Montreal opened its new ballpark in 1928. Shaughnessy took a brief break from sports in 1928, working as a stockbroker in Montreal. However, by 1932 the Depression had impacted his business. This turn of events led him back to baseball. Still, the Royals faced significant challenges, including owing $51,000 in back taxes to the city and the mortgage company that owned the stadium. Compounding their troubles, the property value of the ballpark had dropped by $78,550 since 1928.That drop, coupled with the back taxes and a looming mortgage foreclosure, had the company on shaky financial ground. With the situation looking increasingly dire, Savard – the club’s majority owner after David departed – brought in a new investor with a now-famous last name: Jean-Charles Emile Trudeau, father of future Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau and grandfather of current Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.16

Jean-Charles Emile Trudeau, known as Charlie to his friends, was a wealthy Montreal business owner who made his fortune during the Great Depression by selling a chain of service stations to Champlain Oil Products Ltd. After some convincing, he invested $25,000 into the team, apparently writing “In Protest” on the back of the check, and insisted the club be well-managed. While he may have been reluctant to invest in the club, preferring to watch sports rather than invest in them, he was later a frequent presence at the ballpark. Oscar Roettger, who played for the New York Yankees, Brooklyn Robins and Philadelphia Athletics, recalled seeing young Pierre Trudeau accompany his father to the games. The elder Trudeau also brought other investors to the club, including Lt.-Col. Roméo J. Gauvreau, who, like Trudeau, had made his money in the oil business. Savard agreed to step down as club president so Hector Racine, a mutual acquaintance of Trudeau and Gauvreau who knew little about the sport, could take his place. A prominent figure in Montreal’s garment trade, Racine served on the Board of Trade’s council and led the Canadian Wholesale Dry Goods Association. Savard soon left the club altogether to become president and part-owner of the Montreal Canadiens hockey team. In 1933 the new ownership decided to install lights at Delorimier Downs (as the ballpark was also called) so the team could play at night, as many other International League teams had already done. Night baseball was a hit in Montreal, as fans flocked to Delorimier Downs to watch baseball under the lights.17

Tragedy once again befell the Royals when Trudeau, their majority owner, caught pneumonia and died while accompanying the team at spring training in Orlando in 1935. Gauvreau assumed most of Trudeau’s duties with the club.18

On the field, fans flocked to see the Royals, with more than 300,000 attending the team’s home games during the 1935 season. But off the field, the team’s financial troubles deepened as the value of its assets rapidly depreciated while its tax debt sharply increased. The Montreal Exhibition Company, which by March 1936 owed $75,133 in back taxes, was placed in liquidation. Amid the financial instability, Shaughnessy abruptly resigned as general manager in early August 1936. Shortly after, he became president of the International League. The Royals finished the season in sixth place under new manager Harry Smythe. Meanwhile, the city – which briefly considered owning and operating the ballpark – instead sold it to a local entrepreneur, Joseph Raoul Lefebvre, for $50,000 in 1936. However, the club continued to find itself in dire straits. In a bid to salvage the team, Racine and Pittsburgh Pirates President and Chief Executive William Benswanger struck a deal in 1937. This agreement injected much-needed funds into Montreal and promised to bring exciting young players to the team. Additionally, Racine replaced Smythe as manager with Rabbit Maranville. The deal with Pittsburgh didn’t prove as beneficial as expected. The Pirates sent only a handful of players to Montreal and refused to provide any pitchers, a critical position of need for the Royals. Still, lacking any better options, they renewed their deal with Pittsburgh for 1938. However, Racine swiftly ended ties with the Pirates and pursued a new affiliation with the Brooklyn Dodgers, led by their general manager, Larry MacPhail. In December 1938 the clubs signed a one-year working agreement with an option to renew at the end of the contract. As part of the agreement, according to the Associated Press, the Royals would “have first choice on players the Dodgers decide to release to a league of AA classification.”19

Heading into the 1940 season, Racine wanted more than a working relationship with the Dodgers. He and MacPhail negotiated a deal for Brooklyn to buy the Royals in February 1940 on condition that the Dodgers agree to split the $30,000 cost to upgrade Delorimier Downs equally three ways with the ballpark owners and concession owners. Newspaper reports at the time noted that the Montreal investors kept a controlling interest in the team, with Roméo Gauvreau, Lucien Beauregard (a partner in a local law firm), and the estate of Jean-Charles Emile Trudeau “retaining a majority of shares in the club. All other shareholders have been bought out by Brooklyn.” The Dodgers made the Royals their top farm team. Racine stayed in his role, running the club’s day-to-day operations, but MacPhail and the Dodgers now owned and controlled most of the players. In 1945 the Dodgers assumed full ownership of the ballpark.20

Montreal went on to enjoy a successful 1941 campaign, winning the Governor’s Cup as league champions but losing the Junior World Series to the Columbus Red Birds. The following year brought significant changes to the Dodgers organization with the departure of MacPhail and his replacement by Branch Rickey, the mastermind behind the renowned farm system of the St. Louis Cardinals.21

During the tumultuous years of 1942 to 1945, the Royals struggled to replicate the relative success of the 1941 season. Despite the challenges of World War II, baseball remained a beacon of hope, even as many players left their teams for military service. Nevertheless, Montrealers continued to support the team. In 1945, although they once again won the Governor’s Cup, they fell short of reaching the Junior World Series. Their success drew significant crowds, with 397,517 fans attending during the regular season – the highest in the International League and nearly twice as much as in the previous year – along with an additional 60,000 who came out for playoff games. However, the most memorable moment of the 1945 season came on October 23, 1945, when Royals President Hector Racine announced the signing of Jackie Robinson to play for Montreal in 1946.22

***

The press contingent at Delorimier Downs sprang from their seats, racing to the nearest telephones to relay the groundbreaking news: The Royals had signed an African American player. At that time, such an acquisition was unprecedented. Within the National League ownership circles, an unwritten agreement prevailed: No Black players would be signed. (This period of history is covered extensively in SABR’s Jackie Robinson 75: Baseball’s Re-Integration project.)

Branch Rickey offered Robinson a monthly salary of $600 to play for the Royals, half in Canadian dollars, half in American, along with a signing bonus of $3,500 USD.23

Robinson swiftly showcased his extraordinary skills, securing the International League batting title in 1946 with an impressive .349 average. Not only did he lead the league in walks and runs scored, but he also stole 40 bases. Despite missing nearly 30 games due to leg injuries, Robinson still managed to produce 65 RBIs, further highlighting his exceptional talent and resilience. Robinson’s strong play earned him a spot on the 1946 International League all-star team.24

Robinson’s crowning achievement came as he led Montreal to victory in the 1946 Junior World Series. Montreal was still basking in the afterglow of that memorable season 20 years later, even after the Royals franchise had ceased to exist. The city paid tribute to Robinson by celebrating Jackie Robinson Day on September 10, 1966. Robinson returned to the city, which established a scholarship in his name for the benefit of Black students in Montreal. “The fund will be built up from public donations, and will be administered through a Montreal trust company,” the Canadian Press reported. “J. Louis Levesque, a Montreal financier and horseman, has been named chairman of the fund committee.”25

***

The Royals were never able to recapture the magic of that 1946 season. While Montreal continued to excel on the field, clinching two more Junior World Series titles, in 1948 and 1953, the passionate fanbase that had once rallied behind the team began to noticeably dwindle in size. Season attendance plummeted from close to half a million (typically closer to 600,000 including playoff games) to fewer than 300,000 during their Junior World Series-winning season in 1953. Numerous theories abounded to explain this downturn. Maybe the fans were taking the team’s success for granted, or maybe the product on the field wasn’t as much fun to watch any more with Robinson gone. Some attributed the decline in attendance to the increased availability of major-league broadcasts, or simply the growing variety of entertainment options on television. Whatever the reason, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, who was trying to raise cash to replace Ebbets Field, started exploring options to sell the team. This coincided with a push to bring a major-league team to Montreal, perhaps by relocating the troubled St. Louis Browns. In 1953 the Montreal City Council looked into buying the Royals’ name, territorial rights, and Delorimier Stadium from the Dodgers. However, the plan was abandoned due to the steep asking price of $2.35 million (C).26

Meanwhile, the Royals were hemorrhaging money. Racine conceded that the team lost over $50,000 during the 1954 season, marking its poorest performance in his tenure with the club. He hastened to add that the team wasn’t in dire straits, as the Dodgers profited from other events at Delorimier Stadium and concession sales. However, concerns were growing among the Dodgers management in New York regarding the situation in Montreal.

***

The Royals faced another tragedy in 1956 with the passing of club President Hector Racine. This led to significant upheaval in Montreal’s front office. Lucien Beauregard and Roméo Gauvreau maintained their executive roles, while Rene Lemyre was made the general manager after the departure of Guy Moreau. Additionally, former Montreal Canadiens captain Emile Bouchard joined the club’s board of directors and succeeded Racine as president. Bouchard’s business interests included a downtown Montreal restaurant called Chez Butch Bouchard. The new-look front office wasted no time in making moves that would have a lasting impact on the franchise. In 1956, the Dodgers sold Delorimier Stadium to a real estate company, Sherburn Investment, Corporation under a deal that saw the Royals lease the park until the end of the 1960 season. The beginning of the end for the Montreal Royals arrived in the fall of 1957 with the announcement of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ relocation to Los Angeles for the 1958 season. How could they remain the Dodgers’ top farm team when they were separated by nearly 2,500 miles? While the Royals’ front office outwardly reassured Montrealers of business as usual, Bouchard was quietly assembling a group of local investors in a bid to acquire the franchise. O’Malley rejected their proposal, which aimed to bring the Royals back under local ownership while retaining their status as the Dodgers’ primary farm team.27

The Royals’ attendance hit rock bottom in 1956, ranking last in the league, and saw only slight improvement the following season. Even a run to the 1958 Junior World Series failed to reignite fan interest, with a meager 5,800 fans showing up for the 1959 home opener.28

It got worse the following season. The 1960 home opener drew 8,725 fans, a far cry from the large turnouts the team enjoyed during its heyday. Part of the problem stemmed from the team’s lack of star power, as the Dodgers opted to send their top prospects to another one of their farm clubs in much closer Spokane, Washington. Not surprisingly, with no stars and a losing record, fan interest in Montreal hit an all-time low. The team tried gimmicks and contests in a bid to bring fans back to the ballpark, to little avail.29

The team’s general manager, Fernand Dubois, made efforts to rally the local business community to consider building a new ballpark, but he struggled to garner substantial interest. By then the team was on life support, evident when only 1,016 fans turned out for its final home game on September 7, 1960. A few weeks later, the Dodgers made it official: They were severing ties with the Royals and putting the club up for sale. Joe Remer, secretary of the Sherburn Investment Corporation, which owned Delorimier Stadium, told the Canadian Press that O’Malley told him “[T]he Dodgers have been losing money steadily in Montreal for the last three or four seasons and will not be back in 1961.” With no prospective buyers emerging, the International League assumed control of the franchise. A group of local investors, headed by event promoter Loren Cassina, made an unsuccessful bid for the team. Frank Shaughnessy and Tommy Richardson, his successor as International League president, made a last-minute effort to keep the franchise in Montreal through a community-ownership scheme. Shaughnessy even managed to talk the Dodgers into agreeing to a deal that would see them sell their remaining assets in the Royals franchise. This included everything from the ballpark lights, bats, balls, and uniforms to concession and office equipment, all for $90,000 – a figure he claimed was $35,000 less than what the Cassina group had offered the Dodgers for those assets. The sticking point, however, was the ballpark. Sherburn Investment Corporation and the league remained far apart on the value of Delorimier Stadium. In the end, a deal to keep the franchise in Montreal never materialized, and the International League moved it to Syracuse. Delorimier Stadium was demolished in 1969 to make way for Ecole Polywalénte Pierre Dupuis, effectively removing the last physical reminder of the team from the landscape of Montreal.30

Montreal’s baseball drought proved short-lived. While the sting of losing the Royals lingered, the city didn’t have to wait long for a new chapter. In 1969 the Montreal Expos joined the National League as part of a four-team major-league expansion. Ironically, Walter O’Malley, the man vilified in Montreal for severing the Royals’ ties to the Dodgers, chaired the National League’s expansion committee. In a twist of fate, the man who took baseball away from Montreal played a key role in bringing it back.31

Notes

1 Marc J. Steiner, “Jackie Robinson: History Made at the 1946 Junior World Series,” in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42, Bill Nowlin and Glen Sparks, eds. (Phoenix, Arizona: SABR, 2021), accessed online February 7, 2024.

2 Jonah Keri, Up, Up, and Away: The Kid, the Hawk, Rock, Vlad, Pedro, le Grand Orange, Youppi!, the Crazy Business of Baseball, and the Ill-fated but Unforgettable Montreal Expos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014), 4-5.

3 Keri, 4-5.

4 William Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals: The Minor League Team that Made Major League History (Montreal: Robert Davies Publishing, 1996), 7.

5 Brown, 9.

6 Brown, 9.

7 Brown, 10.

8 Brown, 11; Robert Harry Pearson, Montreal’s Delorimier Downs Baseball Stadium as Business and Centre of Mass Culture, 1928-1960 (master’s thesis, Queen’s University at Kingston, 1999), 21-22.

9 Brown, 11; Marcel Dugas, Jackie Robinson, Un Été à Montréal (A Summer in Montreal) (Montreal: Éditions Hurtubise, 2019), 9.

10 Brown, 12-14.

11 Brown, 14-20.

12 Brown, 21-24.

13 Brown, 23-24

14 Brown, 27-28; Pearson, 60.

15 Pearson, 63; Brown, 28-29.

16 Brown, 33-35; Pearson, 64; Charlie Bevis, “Frank ‘Shag’ Shaughnessy,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, accessed April 21, 2024.

17 Brown, 35-36; “Memories in the Lobby of Mantle and Trudeau,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), December 8, 1979; Dugas, 23.

18 Brown, 40.

19 Brown, 46-55; Pearson, 65-66; Associated Press, “Montreal and Brooklyn Sign Working Agreement,” Globe and Mail, December 23, 1938.

20 Brown, 60-61; Pearson, 23; Canadian Press. “Deal Closed by Dodgers,” Globe and Mail, February 21, 1940.

21 Brown, 73-76.

22 Brown, 85-86.

23 Brown, 93; Dugas, 44.

24 Brown, 105.

25 Canadian Press, “Montreal Will Hold Jackie Robinson Day,” Globe and Mail, September 8, 1966.

26 Brown, 145-147; Pearson, 76.

27 Brown, 161-164; Tom Hawthorn, “Emile ‘Butch’ Bouchard, star NHL defenseman, dies at 92,” Washington Post, April 12, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/emile-butch-bouchard-star-nhl-defenseman-dies-at-92/2012/04/17/gIQAKNx2OT_story.html, accessed April 21, 2024.

28 Brown, 169-171.

29 Brown, 174-175.

30 Brown, 177; Canadian Press, “Dodgers Give Up Montreal Royals,” Globe and Mail, September 14, 1960; Al Nickleson, “IL Rejects Canadian Bid for Montreal Franchise,” Globe and Mail, November 28, 1960; Al Nickleson, “IBL Will Reclaim Royals Franchise from Los Angeles,” Globe and Mail, November 30, 1960; Canadian Press, “Dodgers to Help Montreal Royals Stay in League,” Globe and Mail, December 16, 1960; Pearson, 24.

31 Canadian Press, “Key Dates in Montreal Expo History,” Globe and Mail, September 29, 2004. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/sports/key-dates-in-montreal-expo-history/article1004791/, accessed April 21, 2024.