April 14, 1970: Prayers for Apollo 13 crew at Cubs’ home opener

What’s usually a day of terrific joy was also a day of grave concern.

What’s usually a day of terrific joy was also a day of grave concern.

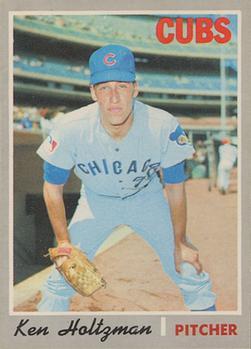

Cubs fans at Wrigley Field for 1970’s home opener welcomed Chicago’s North Side ballclub after the team went 1-3 in its first four games of the season. Southpaw Ken Holtzman pitched a complete game and led the home team to a 5-4 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies on April 14.

But the 36,316 Tuesday-afternoon attendees may have had other matters on their minds, as the world waited anxiously for news regarding the three-man Apollo 13 crew stranded in space: Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert.1

The plan had been for Lovell and Haise to land on the moon in the lunar module, conduct their moonwalking excursions, and dock with Swigert orbiting in the command module for the return trip home. NASA, however, scrapped the moon landing because an oxygen tank had exploded in the service module, forcing the trio to find refuge in the lunar module, which was designed for two astronauts.2

There had been good news from NASA that morning. In the latest of a series of complex, improvised operations designed by engineers and astronauts at NASA’s Mission Control, Apollo 13’s crew directed their spacecraft around the moon to “slingshot” it and gain speed, then fire the spacecraft for nearly 4½ minutes. The maneuver adjusted their course toward Earth. But another danger had emerged. Carbon dioxide levels were rising, which forced NASA engineers to create a device that the crew could construct from the equipment on board to lessen the gas.

The Cubs hosted two dignitaries atop the Land of Lincoln’s political spectrum, Governor Richard Ogilvie and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, in addition to ex-Cubs Lou Boudreau and Gabby Hartnett – the former threw the ceremonial first pitch to the latter.3

Milton Berle, the vaudeville and nightclub comedian turned B-movie star turned TV’s first icon, served as the “emcee” for the pregame festivities, which included putting away the wisecracks and asking the crowd to pray for the safe return of the Apollo 13 astronauts. An Associated Press photo captured the 61-year-old Berle with Ernie Banks and Ron Santo holding their Cubs hats over their heads and bowing their heads for the solemn moment.4

Apollo 13’s ordeal was a somber backdrop that made the game less a distraction and more an afterthought.

Phillies starting pitcher Chris Short had shut out the Cubs on April 7. It was his first game after a back injury limited him to only 10 innings in 1969. In this rematch a week later, however, Chicago tagged the lefty for three runs in the bottom half of the first frame. After bunt singles by Don Kessinger and Glenn Beckert put runners on first and second, Short retired Billy Williams on a fly ball to left fielder Tony Taylor and struck out Santo.

With two down, however, Banks answered the hopes of Cubs fans with a double, knocking in one run and pushing Beckert to third. In the 18th season of a 19-year career, Banks joined with fellow future Hall of Famers Williams and Santo to comprise the Cubs’ heart of the order. Jim Hickman worked the count for a walk and Johnny Callison, a longtime Phil who had come to the Cubs in a November 1969 trade, got the second double of the inning, sending Beckert and Banks across the plate to give Chicago a 3-0 lead.

In the bottom of the third, Chicago readied to expand its lead. With one out, Santo walked and Banks followed with the second hit in his 3-for-4 day. Hickman singled to left, sending Santo to third. It would have been a bases-loaded scenario, but Banks took a wide turn around second base. Taylor fielded the ball and fired to third baseman Don Money. Money tossed it to second baseman Denny Doyle, who was covering third, and Banks was the second out.

Callison’s grounder to Doyle with Short covering first base extinguished the Chicago threat.

The Cubs increased their lead to 5-0 in bottom of the seventh. Dick Selma, who had pitched in 36 games for the Cubs in 1969 and joined the Phillies in the offseason trade that sent Callison to Chicago, relieved Short and gave up a leadoff double to Kessinger; Beckert’s sacrifice moved his teammate to third base. Williams, hitless in 19 at-bats to begin the season, singled to bring home Kessinger. Williams then advanced to third on Santo’s single and scored on a wild pitch by Selma.

It seemed like an easy path to victory when the Cubs took the field with a five-run lead in the top of the ninth. Philadelphia did not go quietly, though.

Taylor led off with a single, but Tim McCarver’s groundball to Beckert forced him out at second base with shortstop Kessinger covering. Money’s triple scored McCarver, breaking up Holtzman’s shutout. John Briggs’s single sent Money home, which put the tally at 5-2.

The rally stalled briefly when pinch-hitter Sam Parrilla, whose major-league career consisted of 11 games in 1970, struck out. But Holtzman gave up a home run to Ricardo Joseph, pinch-hitting for rookie shortstop Larry Bowa, which brought the Phillies within a run of tying the game.

The score stayed at 5-4; Doyle’s groundball to Santo at third base was the last at-bat.

Cubs manager Leo Durocher admitted that Joseph, who hit .273 in 99 games during the 1969 season, prompted worry about Holtzman, who went 17-11 in 1970: “There’s no way he would have faced Joseph if he had been the tying run,” the manager said.5

A victory on Opening Day should have been a positive experience for Cubs fans, especially with the uncertainty surrounding Apollo 13. But there were several fistfights in the stands. After the final out, “hundreds of young men,” as the Chicago Tribune reported, went on the field.6 Three intruders wrestled Beckert to the ground; one threw a punch at him after he freed himself.7 But the crowd dispersed, and no arrests were made.8

Holtzman was a member of the Illinois National Guard at the time. Tribune scribe Richard Dozer joked, “He was armed with ball and glove – altho [sic] sidearms may have been a better order of the day.”9

Apollo 13’s command module splashed down in the South Pacific four days later. When the astronauts had separated from the service module, they saw the effect of the explosion. “There’s one whole side of that spacecraft missing,” said Lovell.10

The drama and danger did not sway NASA from its continued mission of landing on the moon and gathering data. The NASA administrator, Dr. Thomas O. Paine pledged, “The public has learned from the casualty of Apollo 13 that the business of exploring space is indeed always risky. But there are always men who are willing to accept these risks to explore new areas.”11 NASA ended Project Apollo with Apollo 17 in December, 1972.12

Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton, and Kevin Bacon starred as Lovell, Haise, and Swigert in the 1995 movie Apollo 13, directed by Ron Howard. It introduced the story of NASA’s finest hour to generations too young to remember the crisis or who were not yet born when it happened. Older generations were reminded of this extraordinary American tale.

The film included a tangential, real-life incident. Swigert had forgotten to file his taxes before the April 15 deadline, but he deserved an extension because he was out of the country.

On April 19 President Nixon gave the Medal of Freedom to the Apollo 13 operations team in Houston. In his remarks, the president acknowledged the flight’s tremendous resonance: “The three astronauts did not reach the moon but they reached the hearts of millions of people in America and in the world.”13 After the ceremony, he flew to Honolulu with the astronauts’ families to meet the space voyagers and present the medal. “I hereby declare that this was a successful mission – a great mission,” said Nixon.14

Sports fans are prone to calling their exemplars “heroes” because of athletic exploits. But the Apollo 13 astronauts – along with NASA’s Mission Control staff – truly earned that label in mid-April 1970. Opening Day and other baseball matters seemed less important as the world stood on the precipice of losing the first voyagers in what William Shatner had called the final frontier in his narration for the opening of Star Trek.15

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Laura Peebles and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the Sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for pertinent material and the box scores noted below.

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1970/B04140CHN1970.htm

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN197004140.shtml

Notes

1 NASA had benched Ken Mattingly for Swigert two days before the launch on April 11. It was a precaution because Charlie Duke, a member of Apollo 13’s backup crew, had the measles but Mattingly never had them as a child. Hence, he was not immune. Because of Duke’s proximity to the crew and Mattingly’s possible exposure, NASA played it safe and substituted Swigert lest Mattingly get sick in space. Mattingly was the Command Module pilot on Apollo 16. He also flew on two Space Shuttle missions.

2 “The Apollo 13 Accident,” NASA, https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/ap13acc.html (last accessed March 26, 2022). An insider’s account of Apollo 13 can be found in the 1994 book Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13, by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger.

3 Tom Bergstrand, “Time Out: Brisk Home Opener for C-C-Cubs,” Moline (Illinois) Daily Dispatch, April 15, 1970: 49.

4 Berle became the host of NBC’s comedy-variety program Texaco Star Theater in 1948, which is largely considered the starting point for television’s escalation to becoming a mass medium.

5 Richard Dozer, “Outlast Phils in Rebellious Home Opener,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1970: Section 3, 1.

6 Dozer.

7 Cooper Rollow, “Cubs Demand Police Help to Curb Unruly Crowds,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1970: C1.

8 Rollow.

9 Dozer.

10 “The Apollo 13 Accident.”

11 Ronald Kotulak, “Apollo 13 Crisis Won’t Slow U.S. Space Exploration, Says NASA,” Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1970: 2.

12 There were six moon landings in Project Apollo.

13 “Operations Team Gets Medal First,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 19, 1970: 3.

14 Gene Hunter, “Apollo 13, Lucky You Come Hawaii,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 20, 1970: 15.

15 As of the publication of this article in 2022, the deaths of Russia’s three-man Soyuz 11 crew in 1971 are the only ones above the Kármán line, which is considered the separator between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space. It’s 62 miles above Earth. Soyuz 11 had launched on June 6 and docked with the Salyut 1 space station, where the crew stayed until June 29, then returned to the Soyuz capsule and headed for reentry. The recovery team found cosmonauts Georgi Dobrovolski, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev dead. The conclusion was a fall in air pressure, which caused oxygen deprivation. Thomas O’Toole, “Valve Mishap Blamed for Soyuz Deaths,” Washington Post, October 29, 1973: A1.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 5

Philadelphia Phillies 4

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.