April 18, 1947: Jackie Robinson tallies first career homer and first RBI against rival Giants

The measurement of Jackie Robinson’s success as the first major leaguer to break the color barrier was based less on statistics than on his courage, temper, and mental acuity. But the experiment conceived by Branch Rickey and performed by Robinson would have been a fruitless endeavor had Robinson not produced on the field.

In fact, according to author Jonathan Eig in his book Opening Day, there was no certainty early in the 1947 season that Robinson would be an everyday player.1

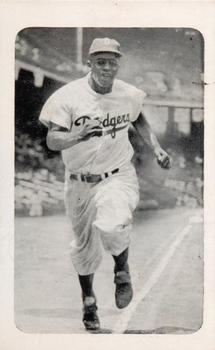

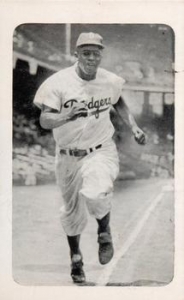

But Robinson quickly put aside any questions of his staying power. And on a Friday afternoon at the Polo Grounds, in his introduction to the famed Dodgers-Giants rivalry, Robinson recorded his first big-league home run and run batted in on one third-inning swing against Dave Koslo.

Going 2-for-4 on a day in which Brooklyn managed seven hits, Robinson accounted for half his team’s scoring – the second of the four runs being a product of his speed and daring on the basepaths. In spite of these efforts, the Giants used six long balls to pull away to an easy 10-4 victory played in 2 hours and 10 minutes.

After an initial two-game series at Ebbets Field in which the Dodgers took both from the Boston Braves, Jackie Robinson played in his first major-league game beyond the confines of Flatbush. But he was not without his legion of supporters. Out on Eighth Avenue, vendors were selling “I’m for Jackie” buttons.2

The Polo Grounds stood on the outskirts of Harlem, a neighborhood with a heavy Black population that had risen to about 700,000 by 1947,3 some of whom planned to attend the game to cheer their hero on.

However, this contingent of Robinson rooters had much apprehension, partly due to the volatile area Harlem had become.

“It was unclear if black Americans were on the brink of great gains or terrible troubles, but they were clearly on the brink,” Eig wrote.4

Those tensions were amplified by a contest between the Dodgers and Giants – a cross-borough rivalry as combative as any in baseball. There was fear that the tensions that simmered throughout the local area might escalate.

Wrote Eig: “As thousands of white New Yorkers traveled to Harlem by Checker cab and train to see the games, scores of police officers – most of them white – kept careful watch to make sure fans got in and out of the neighborhood safely. … Dodger-Giant games were among the most contentious of all, dividing ethnic groups and even families. But there had never been big black crowds at a Giants game, at least not that anyone could remember. Suddenly, with the arrival of Robinson, much of black Harlem began pulling for the Dodgers.”5

Among those concerned about what might happen was National League President Ford Frick. Despite being very accepting of Robinson’s arrival to the major leagues, Frick was worried about what might take place inside and outside the ballpark.

He “suggested that it might be a fine idea if Robinson were to sprain an ankle and miss a few games,” Eig wrote.6

With temperatures approaching 60 degrees, the paid crowd was 37,546 – a fairly large audience for a weekday afternoon. It proceeded without notable incident and certainly had its moments when the rookie performed to the best of his capabilities. But while there was relative tranquility in the stands, there was unrest within the Dodgers’ hierarchy – as Robinson and the other Dodgers watched the managerial carousel continue to spin.

Burt Shotton, a soft-spoken 62-year-old grandfatherly figure, had recently been named manager. He was replacing fill-in Clyde Sukeforth, who skippered the first two games (and coincidentally was the man who first scouted Robinson in the Negro Leagues). Shotton replaced Leo Durocher, who had been suspended for a year by Commissioner Happy Chandler just before the season began over allegations of gambling associations.

For the third time in as many games, Robinson batted second and played first base. His initial turn at the plate versus Giants starter Koslo resulted in a fly out to shallow center field.

Pee Wee Reese got the Dodgers on the board with a run-scoring fly ball in the second, only to be answered by right-hand-hitting second baseman and future Dodger killer Bobby Thomson with a home run to left field, a preview of October 1951 when he did the same to give the Giants the pennant over the Dodgers.

Brooklyn had the opportunity to answer in the top of the third inning – with Robinson providing that response.

Leading off, Robinson took Koslo’s first offering for a strike, high and inside. The next pitch was a little lower and a little more over the plate. He connected – a tracer that struck the left field’s upper-deck scoreboard.7

It was the first of 137 home runs and 734 RBIs Robinson would accumulate over the course of a 10-year major-league career that stands alone in history.

“As Robinson trotted around the bases, toes turned inward, his fans stood and laughed and hollered,” Eig wrote in Opening Day.

Jackie didn’t tip his cap to acknowledge the partisan support. Greeting him at home plate was the next batter, Tommy Tatum. The photo of a White man exchanging a handshake with a Black man ran on the back page of the next day’s New York Daily News.8

The round-tripper pushed the Dodgers ahead, 2-1. In retrospect, it was a milestone moment in a career unparalleled in baseball and society. But in the context of the game itself, the homer was overshadowed by an onslaught of Giants power.

Dodgers starter Vic Lombardi came into the day with a career 9-0 mark versus New York. Hopes for adding to that perfect record were hurt when he was ambushed for two more home runs in the third inning, by Bill Rigney and Johnny Mize.

Later, after Lombardi departed down 4-2, it was Ed Chandler’s turn to suffer at the mercy of New York bats. With one out in the bottom of the sixth inning, Willard Marshall gave the crowd in right field a souvenir. Two batters later, Thomson belted his second of the afternoon.

Robinson watched a half-dozen New York batters take the slow trot around first base, the final blast a grand slam by Rigney off Hank Behrman in the bottom of eighth to all but ensure a Giants victory.

The outcome had remained in doubt thanks to a patented Robinson-manufactured score that began with his typical intrepid baserunning. As was explained in the New York Daily News, “Robinson had opened the eighth with a bloop single to right, rushed to second on Marshall’s well-meant but wild peg to first as Jackie took the big turn, and scored on a couple of outs.”9

Carl Furillo soon tripled and scored on another Giants fielding miscue, as Brooklyn cut the New York lead to 6-4. However, the Dodgers’ comeback efforts were squashed once Rigney connected with the bases loaded.

Robinson’s successful day at bat would’ve been even better had more luck been on his side. A liner in the fifth inning found its way into the glove of third baseman Jack Lohrke, who fired to first base to double off Eddie Stanky.10 But Robinson more than made up for it with solid defense. He handled without fault each of his eight chances at first base, a position he had just come to learn prior to the season.

While the disparity in the final score leaned heavily in the Giants’ favor, the final standings for 1947 showed a complete reversal: The Dodgers finished 13 games better than their foes from Manhattan and would win 14 of the 22 times they played each other.

As for Robinson, who tied for the team lead in homers with 12 while also driving in 48 runs and stealing 29 bases en route to being the first-ever Rookie of the Year, his perseverance and courage are deservedly etched in history.

The New York Age, one of New York City’s most prominent Black newspapers, foretold what the near future held in Robinson’s remarkable journey.

“For Jackie, the situation becomes even more difficult. He was a guinea pig before. He is even more of one now. Every human misstep he may commit will be watched. His triumphs will be exaggerated, and his faults rendered disproportionate. However, we have confidence in his power to keep his head and watch his step so that the important victory which has been won may be extended throughout the game.”11

Sources

In addition to the references cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Jonathan Eig. Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 62.

2 “Ottmen Win, 10-4, with Six Home Runs,” New York Times, April 19, 1947: 18.

3 Eig, 64.

4 Eig, 64.

5 Eig, 66.

6 Eig, 63.

7 Eig, 68.

8 Eig, 69.

9 “Shotton Named Dodger Pilot; Six Giant Homers Win 10-4,” New York Daily News, April 19, 1947: 25.

10 “Mild-Mannered Shotton Opposite of Durocher as Manager,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 19, 1947: 6.

11 “Passing the Bar,” New York Age, April 19, 1947: 6.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 10

Brooklyn Dodgers 4

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.