April 6, 1871: Boston Red Stockings take the field for the first time

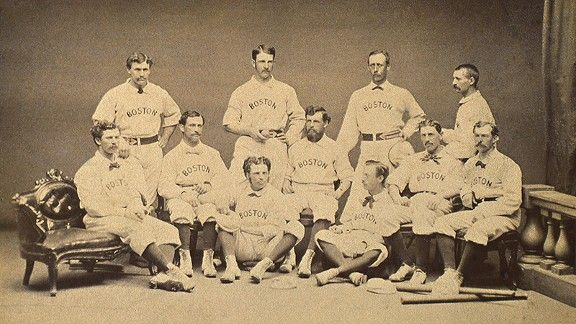

“Well, back in 1871, my great-great-grandmother had a boardinghouse in Boston,” recounted a sparkling, white-haired lady speaking with appraiser Leila Dunbar on a PBS episode of Antiques Roadshow. “And she housed the Boston baseball team. Most of them had come from the Cincinnati Red Stockings and were among the first to be paid to play baseball.” Her unique collection, appraised at $1,000,000, contains baseball cards and personal correspondences of the 1871-1872 Boston Red Stockings, Boston’s first professional baseball team. They are also the ancestors of the Atlanta Braves and the first Boston team to wear red socks.

They had sparkled in those red and white uniforms when they came to Boston in the summer of 1870, and Boston businessman Ivers Whitney Adams took notice, particularly of baseball’s Wright brothers, George and Harry, who were touring the East Coast with the legendary Cincinnati Red Stockings, the nation’s first professional baseball team. Adams had begun dreaming of a professional baseball club in Boston since January of that year,1 and was convinced that if professional baseball could be a reality in Boston, he needed these talented brothers. Adams began a correspondence and even made a trip to Cincinnati to talk further with George and Harry.2 George Wright then arrived in Boston in November,3 and met Adams at Boston’s Parker House, shortly after the Cincinnati team disbanded. On December 3, the Boston Journal verified rumors of a new professional team in the works and said that “Boston shall possess a nine, composed of gentlemanly players, whose unquestionable skill and ability will make it second to none in the country.”4

The Wrights began constructing the Boston team. They brought along first baseman Charlie Gould and catcher Cal McVey from their old Cincinnati club, then signed pitcher Albert Spalding, second baseman Ross Barnes, and outfielder Fred Cone of the Rockford, Illinois, club. They also brought along their socks. “Back in Cincinnati,” historian David Voigt wrote, “not even (Harry Wright’s) best friends forgave him for taking the name ‘Red Stockings’ to Beantown.”5

The Boston club was officially organized at the Parker House on January 20, 1871. “Boston can now boast of possessing a first-class professional Base Ball Club,” wrote the Journal.6 The Boston Base Ball Association was now formed with $15,000 in stock divided into 150 shares.7 The next step was to pay the $10 membership fee and join the new National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, organized on a rainy night in Collier’s Rooms upstairs saloon at 13th Street and Broadway in New York City on March 17, 1871. The first professional baseball league was under way.8

The new Boston team practiced for three weeks, then on April 6 the players were ready for their first exhibition game. “With a month of steady practice,” wrote the Journal, “they will be in a condition to contest for the supremacy with the best clubs in the country.”9

The game was between “the new Boston professional nine and a strong nine selected from the best amateurs in this vicinity,” wrote the Journal. The “picked nine,” according to the Boston Herald, consisted of players from the “Harvard, Lowell, and Tri-Mountain clubs.”10 The game was played on the leased Union Grounds, then being referred to as the “Boston Grounds” by the newspapers, and was later named the South End Grounds. “The grounds were not in the best condition owing to the rains of the past ten days,” wrote the Journal.11

This inaugural 1871 game stirred up huge interest in Boston. The crowd was electric, “for there assembled on the grounds of the club yesterday afternoon, full five thousand persons to witness the opening game of the Boston Nine,” wrote the Journal, “thus being a larger number than ever assembled before on these grounds.”12 The Herald estimated a crowd of 6,000, and noted that the crowd was “larger than ever seen here before, and excepting the Peace Jubilee, probably the largest crowd which ever came together on one occasion in this city.”13 Fans were standing on the fence and on nearby rooftops to watch this inaugural event.

The crowd applauded as the new Boston team took the field, looking very much like the old Cincinnati club, with a white flannel shirt, knee breeches, cap, red belt, red necktie, white shoes, and the name of the club in block letters across the shirt. And we mustn’t forget the red stockings, which also made their debut that day, making this “the neatest uniform yet originated,” according to the Journal.14

While no play-by-play account of the game exists, it’s safe to say the 41-10 Boston win was historic but not a classic. After a scoreless first inning, Boston broke out with 10 runs in the second, through some “fine heavy hits, assisted by field errors of their opponents.”15 “This was a long inning,” the Journal elaborated.16 Three more runs came across in the third inning, with runs from Sam Jackson, George Wright, and Barnes, and the score was now 13-0 Boston. They added 11 more runs in the fourth inning, and then the Picked Nine answered with a run of their own to cut Boston’s lead to 24-1. Both teams scored six times in the sixth inning, the Picked Nine’s runs mostly coming courtesy of Boston errors. The lead through seven innings was Boston 32-9, and the final score of 41-10 ended the first game of a Boston professional baseball team. Boston’s George Wright had four total bases in the game and scored four runs, while Harry Wright also scored four times. Jackson scored seven runs, McVey six, and Gould five. Spalding pitched the entire game for Boston.

For the Picked Nine, third baseman Frank Barrows scored twice, as did right fielder Dave Birdsall, a Boston player who played for the Picked Nine that day. First baseman Maxson Mortimer “Mort” Rogers led the Picked Nine with three hits. Left fielder William Ellery Channing Eustis, second baseman Horatio Stevens White, center fielder John Cheever Goodwin, and shortstop Archibald McClure Bush were Harvard players. Catcher William M. “Met” Bradbury, pitcher James D’Wolf Lovett, and Rogers were players from the Lowell team. Barrows was from the Tri-Mountain club, and would later that season play 18 games for Boston, the only player of the Picked Nine to play professional baseball. “It is quite apparent,” the Journal remarked, “that a nine picked from two or three clubs, be they ever so good players, do not do so well as in their own club.”17

“Of course the Picked Nine were defeated,” espoused the Harvard Advocate, “but not ‘of course’ as badly as the result shows. Never was the fact made equally manifest that working together constitutes a club’s strongest point. The men played each for himself, and the effect was a brilliant series of abortive efforts at even medium play.”18

Boston fans had now seen the stars of the old legendary Cincinnati Red Stockings who were now their Boston Red Stockings. “George Wright fully maintained his reputation as the model base ball player of the country,” wrote the Journal. “Some of his stops, fly catches and throws Thursday equaling anything seen on a ball field. … Harry Wright also played well up to his usual standard of excellence. … McVey bids fair to succeed to the laurels of catcher par excellence of the country. … Spalding will rank among the best professional pitchers of the country. He has good command over the ball, which he sends into the bat at a speed somewhat less than a cannon ball.”19

Today, Boston’s MBTA subway rumbles into Ruggles Station, and busy Northeastern University students and other hurried Bostonians pass by the spot where the South End Grounds once stood. Only an overlooked, lonely plaque remains to tell us of the origins of professional baseball in Boston and of the beginnings of the Atlanta Braves franchise.

Except for a few extraordinary baseball cards.

This article was originally published in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the text, the author benefited from the following sources:

Batesel, Paul. Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012).

Devine, Christopher. Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003).

Harvard Book: A Series of Historical, Biographical, and Descriptive Sketches. Harvard University Archives. Retrieved May 16, 2015, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.arch:15010.

Harvard College Class of 1873 Ninth Report of the Secretary. Boston: Rockwell & Church Press, 1913. Retrieved May 16, 2015. https://books.google.com/books?id=tdglAAAAYAAJ&lpg=PA20&ots=3R35K_uW_d&dq=John%20Cheever%20Goodwin%20Harvard%20class%20of%201873&pg=PA19#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Report of the Secretary of the Class of 1871 of Harvard College, Issue 11. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Class, 1921. Retrieved May 16, 2015, https://books.google.com/books?id=vCZOAAAAMAAJ&dq=inauthor%3A%22Harvard%20university.%2C%20Class%20of%201871%22&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Articles

Bevis, Charlie. “Ivers Adams,” The Baseball Biography Project, SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/813abb83, accessed May 1, 2015.

Brooks, Jimmy. “Columbus Lot Slabbed Where Boston’s Historic South End Grounds Once Stood,” Huntington News, January 9, 2014. Accessed May 16, 2015, https://huntnewsnu.com/2014/01/columbus-lot-slabbed-where-bostons-historic-south-end-grounds-once-stood/.

Thorn, John. “Baseball’s First League Game: May 4, 1871,” https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/2012/02/07/baseballs-first-league-game-may-4-1871/ accessed May 12, 2015.

Voigt, David Quentin. “The Boston Red Stockings: The Birth of Major League Baseball,” New England Quarterly vol. 43 no.4 (1970), 531-549.

Websites

“1871-1872 Boston Red Stockings Archive.” Antiques Roadshow. Public Broadcasting System, 2014. https://pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/season/19/new-york-ny/appraisals/1871-1872-boston-red-stockings-archive–201407A12, accessed May 15, 2015.

Notes

1 Based on Adams’s recollection at the founding of the team a year later. “The Boston Base Ball Club: Meeting of the Stockholders — A History of the Enterprise — Organization of the Association and Election of Officers,” Boston Traveler, January 21, 1871.

2 George V. Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club … A Concise and Accurate History of Base Ball From Its Inception (Boston: M.F. Quinn & Co., 1897), 61 [Google Books version]. A special petition was submitted to the Massachusetts Legislature to grant a charter for a new baseball club with no less than $10,000 capital stock at $100 per share. Acquiring the services of George and Harry Wright was now the top priority. “A Boston Professional Base Ball Nine,” Boston Journal, November 15, 1870: 2.

3 “Base Ball Matters,” Boston Journal, November 25, 1870: 4.

4 “Boston and Vicinity: The Boston Professional Nine,” Boston Journal, December 3, 1870: 3.

5 David Quentin Voigt, American Baseball: From the Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 34.

6 “The Boston Base Ball Club: A Permanent Organization Effected All the Players Engaged,” Boston Journal, January 21, 1871: 1.

7 Adams was elected president of the club, along with vice president John A. Conkey, treasurer Harrison Gardiner, secretary Harry Wright, and “fifth director” G.H. Burditt. “The Boston Nine. Organization of the Boston Base Ball Association — History of the Movement — Adoption of By-Laws and Election of Officers,” Boston Herald, January 21, 1871.

8 The Boston club was one of eight teams pay the $10 fee to join. The others were the Philadelphia Athletics, New York Mutuals, Washington (D.C.) Olympics, Troy (New York) Haymakers, Chicago White Stockings, and two teams sharing the same name: the Cleveland Forest City club and the Rockford (Illinois) Forest City club. Before the season began, a ninth club joined: the Fort Wayne (Indiana) Kekiongas.

9 “Base Ball: Opening Match of the Boston Club — The Picked Nine Defeated, 41 to 10 — Other Matches,” Boston Journal, April 7, 1871: 2.

10 “Affairs About Home: Baseball,” Boston Herald, April 8, 1871: 4.

11 “Base Ball: Opening Match of the Boston Club.” The Union Grounds opened on June 19, 1869, on the east side of the Providence Railroad track, near Milford Place on Tremont Street. The game was between the Brooklyn Atlantics and a picked nine from the Lowell, Massachusetts, and Tri-Mountain clubs. The Boston Herald reported that despite the large crowd the game was long and tedious as foul balls over the fence had to be chased down. See “Affairs About Home.”

12 “Base Ball: Opening Match of the Boston Club.”

13 “Affairs About Home: Baseball,” Boston Herald, April 8, 1871: 4. The “Peace Jubilee” was a massive music festival in Boston organized by band leader Patrick S. Gilmore to celebrate the end of the Civil War. The celebration was held for a week in June 1869, and included thousands of instrumentalists and singers in a specially built coliseum to hold the enormous crowd. Among the celebratory masses were President Ulysses S. Grant and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes. This was the first so-called “monster” festival in 19th century America. See Roger L. Hall. “Peace Jubilees,” Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed May 5, 2015, https://oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2252160.

14 Ibid.

15 “Base Ball: Opening Match of the Boston Club”

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 “The Games on Thursday,” Harvard Advocate, Vol. XI. No. V, April 14, 1871, 69. Retrieved May 9, 2015. books.google.com/books?id=PN3OAAAAMAAJ&lpg=PA69&ots=E3t8MgYPD&dq=%22picked%20nine%22%20%22eustis%22&pg=PA69#v=onepage&q&f=false.

19 “Base Ball: Opening Match of the Boston Club.”

Additional Stats

Boston Red Stockings 41

Picked Nine 10

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.