August 26, 1891: John McGraw beats back butterflies to ignite game-winning rally in debut

No manager in major-league history was more inclined to use left-handed shortstops than Billy Barnie of the American Association’s Baltimore Orioles. In his nine years at the helm there, from 1883 through 1891, he used seven of them,1 most notably Jimmy Macullar, who was his everyday shortstop for three seasons.2

No manager in major-league history was more inclined to use left-handed shortstops than Billy Barnie of the American Association’s Baltimore Orioles. In his nine years at the helm there, from 1883 through 1891, he used seven of them,1 most notably Jimmy Macullar, who was his everyday shortstop for three seasons.2

When George Van Haltren, the last portsider to play shortstop for Barnie,3 faltered during the 1891 season, the Baltimore skipper’s search for a suitable replacement uncovered John McGraw, a scrawny 18-year-old with experience well beyond his years. McGraw overcame a case of nerves to help secure a comeback win in his late-August debut, jump-starting the Orioles’ transformation from also-rans into the team that dominated the National League in the mid-1890s and modernized how the game was played.4

Members of the Association since 1882, the Orioles had never finished above third place. They left before the 1890 season, moved to the Atlantic Association when the National League declined to invite them in, then rejoined the American Association in August of that same season after the short-lived Brooklyn Gladiators folded. The collapse of the Players’ League in January 1891, after one season of competition, presented an opportunity for Baltimore to improve, with many former PL players looking for a team.

One of those was Van Haltren. Splitting his time between pitching and the outfield, in 1890 he hit .335 and won 15 games with the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders, similar to the numbers he’d posted with the NL’s Chicago White Stockings a year earlier. Van Haltren shocked the baseball world in early 1891 when he signed a two-year contract with the Orioles rather than return to Chicago.5

Contrary to newspaper reports that Van Haltren would start in left field,6 shortstop is where Barnie had him start the season, looking past the fact that Van Haltren had played only six games there in his major-league career. Bumped to a utility role was the incumbent, Irv Ray, who had hit a team-leading .360 and compiled an above-average fielding percentage (.894) during Baltimore’s brief Association campaign the year before.7

A flawless performance by Barnie’s shortstop-in-training during an April 27 contest helped put the Orioles in first place and impressed one skeptical Baltimore Sun sportswriter enough to headline his game summary “Van Haltren Can Play Short Stop.”8 But poor team play in May and early June dropped Baltimore into third place and wore Barnie’s patience thin. Despite “chid[ing] the men for their bad playing,” he saw “the same mistakes … repeated daily.”9

With Van Haltren’s play at shortstop having been well below average,10 Barnie temporarily moved him to left field and reinstalled Ray at shortstop. Two weeks later, after losing to the sub-.500 Cincinnati Kelly’s Killers with Van Haltren back at short, Barnie vowed to bring on a new shortstop and second baseman (the latter to replace 10-year veteran Sam Wise).11

Barnie soon signed slick-fielding shortstop Joe Walsh from the Omaha Lambs,12 then learned that Walsh wouldn’t arrive until the Omaha season ended, in mid-September. Unwilling to wait that long to remake his middle infield, Barnie signed another shortstop: McGraw, of the Illinois-Iowa League Cedar Rapids Canaries.

Despite his youth, the 5-foot-7, 120-pound McGraw had a résumé few could match. At 17, he’d played alongside major leaguers as a member of the American All-Stars during an exhibition tour of Cuba in the winter of 1890 and in several spring-training exhibition games that followed. McGraw parlayed that experience into what he claimed were 28 offers for the 1891 season. “I looked over all the offers carefully and then decided to grab the job that paid the most money, no matter where I had to go. This happened to be Cedar Rapids.”13

Referred to as Little McGraw or Mac in local newspapers, McGraw impressed fans, the press, and players alike in Cedar Rapids, including Cap Anson after an exhibition game against Anson’s White Stockings.14 He was praised in local newspapers for his overall play. But when word got out that McGraw was leaving for Baltimore, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette called him dishonorable for jumping his contract.15

As McGraw made his way to Maryland,16 the Orioles continued to disappoint. During a loss to the visiting sub-.350 Washington Statesmen, “the drowsy home team wander[ed] about as if in beautiful dreamland instead of a ball field.”17

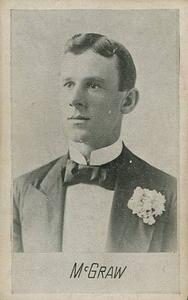

McGraw debuted on Wednesday, August 26, in the opening game of a two-game series at Union Park with the Columbus Solons. “Another [Barnie] experiment,” Sporting Life called him, a weak hitter unlikely to “fill up the [Orioles shortstop] hole very much.”18 The Baltimore Sun was more upbeat, deeming McGraw “a good hitter and base runner,” who “in fielding his position is said to go for everything which comes anywhere near his territory.”19 The Sun also passed along praise from several Columbus players who’d seen McGraw play.20

A crowd of nearly 2,000 was on hand for a matchup that featured the Orioles’ Egyptian Healy, a 22-game winner in 1890 for the Association’s Toledo Maumees, facing Solons southpaw Phil Knell, a 22-game winner in 1890 for the Players’ League Philadelphia Athletic.21

The Orioles elected to bat first, and scored before an out was recorded. Leadoff batter Curt Welch, whose “$15,000 slide” made him a household name in 1886,22 singled and moved to second on a walk to Van Haltren. Both runners advanced on a double steal, with Welch scoring on a wild pitch with slugger Perry Werden batting.23 With two out and runners on second and third, McGraw, swimming in a uniform four sizes too big for him,24 made his first major-league plate appearance. He struck out.25

Columbus responded with three runs in the bottom of the first. An error by McGraw on an easy grounder put speedy Jack Crooks on first.26 “I was so nervous,” McGraw recalled over 30 years later, “I kicked it all over the lot.”27 Hits by Tim O’Rourke and Charlie “Home Run” Duffee28 brought home Crooks and moved O’Rourke to third. O’Rourke, a future Oriole, scored on a foul popup to first baseman Werden.29 Duffee advanced to third on the play and scored on a sacrifice by Larry Twitchell.

Baltimore came back to tie the score in the third on a two-run double by their new second baseman John O’Connell, who’d made his major-league debut the previous weekend.30 Basking in the glow of his first major-league hit, he was promptly picked off.

Van Haltren’s error on an easy fly ball opened the door for the Solons to take back the lead in the fourth. A single by Mike Lehane scored one run, and a sacrifice fly by Knell scored another to give Columbus a 5-3 lead.

Welch single-handedly cut the lead to a single run the next inning when he walked, stole second, and came around to score on another wild pitch by Knell.

Baltimore took the lead back in the sixth. With one out, McGraw stroked his first major-league hit to center and advanced to second when center fielder Duffee fumbled the ball.31 He took third on a passed ball by catcher Jim Donahue, then was joined in scoring position by Pete Gilbert, who drew a walk, then stole second. Robinson’s single brought both McGraw and Gilbert home to put the Orioles up for good, 6-5.

Four men reportedly reached base in the final three innings but no further details were published in newspaper accounts. Two hours after it started, the Orioles had their first two-game winning streak at home since mid-July.32

Afterward, the Baltimore Sun attributed McGraw’s first-inning stumbles to what we now call butterflies, but complimented his baserunning and his play on defense. “McGraw runs to the ball, and does not wait until it comes to him.”33 The combination of O’Connell and McGraw brought life to the Orioles infield as well. A St. Louis Globe-Democrat sportswriter said the Orioles’ two new men “made a favorable impression, McGraw especially playing a fine game.”34

After a dominating 12-2 victory the next day, the Sun saw a “sudden change in the whole team.” The club’s “new blood,” they said, was making the team “more anxious to win than formerly and try harder.”35

McGraw spent the next three weeks at shortstop, but his erratic play there prompted Barnie to try the latecomer Walsh at shortstop and alternate McGraw between second base and right field.36

In late September, Barnie resigned and was replaced by Van Haltren for the Orioles’ last six games of the season.37 McGraw played in right field for every one of them.38

Over the next two seasons, McGraw split his time between the infield and outfield for his new manager, Ned Hanlon. In the summer of 1893, McGraw became the Orioles’ leadoff batter and in 1894, their regular third baseman. A ruthless competitor who evolved into what one sportswriter called “the toughest of the toughs,”39 McGraw was instrumental in Baltimore securing the pennant that year and the two that followed, initiating his distinguished four-decade career as a major-league player and manager.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.com for pertinent material. He also consulted Don Jensen’s SABR biography of John McGraw, Charles F. Faber’s SABR biography of Jimmy Macullar, and McGraw’s autobiography, My Thirty Years in Baseball (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1923). Other sources included box scores and game summaries published in the Baltimore Sun, Boston Globe, Columbus Dispatch, and St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

Notes

1 Left-handed shortstops racked up 331 game appearances for Baltimore during the nine years that Barnie was at the helm (1883 through 1891). Over that same period, there were 405 left-handed-shortstop game appearances combined for every other AA, PL, NL, and Union Association team. From 1871 through 2022, across all major leagues, including the National Association and the Negro Leagues, the National League Philadelphia Phillies are the only team other than the Orioles to have more than 100 lefty-shortstop game appearances, with 279.

2 Macullar, the career record-holder for games played by a left-handed shortstop (325), played 287 of them for Baltimore in his three seasons there.

3 In addition to Van Haltren and Macullar, the other left-handed shortstops to play for Barnie in Baltimore included Bill Gallagher (4 games in 1883), Phil Baker (1 game in 1883), Sam Trott (1 game each in 1885 and 1887), and Bill Greenwood (28 games in 1888, along with 86 games at second base). Southpaw hurler Matt Kilroy also filled in at shortstop for two innings during a game in 1887. Van Haltren, who played 59 games at shortstop before being moved to other positions, was also the next-to-last left-hander in major-league history to lead his team in games played at shortstop. The Philadelphia Phillies Billy Hulen played shortstop for 73 games during the 1896 National League season, nearly double the number of games played there by any other Phillie.

4 For a detailed discussion of how the 1890s Orioles ushered in many elements of modern baseball, see Burt Solomon, Where They Ain’t (New York: The Free Press, 1999).

5 Van Haltren’s Baltimore salary was reportedly a scant $100 more per year than the “all-the-year-around” offer he received from the White Stockings. His Orioles contract called for him to receive $3,500 per season, with $1,000 provided in advance. National League executives insisted that Baltimore release him back to Chicago, which in the absence of an agreement between the leagues to honor one another’s contractual commitments, the Orioles refused to do. “Our National Game,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 29, 1891: 12.

6 See, for example, “Billy Barnie Talks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 1, 1891: 3; and United Press, “Van Haltren to Play at Baltimore,” Mansfield (Ohio) Sunday News, March 1, 1891: 1.

7 During the Orioles’ 38-game 1890 season, Ray, who was Barnie’s only shortstop that year, had the second highest batting average among Association hitters with over 150 plate appearances, and his fielding percentage ranked 7th out of 16 Association shortstops with at least 100 chances.

8 “Batting Wins,” Baltimore Sun, April 28, 1891: 6.

9 “Gloom and Disappointment,” Baltimore Sun, June 10, 1891: 6.

10 In his last start at shortstop before being moved to the outfield, Van Haltren let a grounder go between his legs in the second inning of a game with the last-place Washington Statesmen. Van Haltren’s error gave Washington it’s fifth run in a game they won 6-4, and may have precipitated Barnie’s decision to move him the next game. Van Haltren’s .850 fielding percentage at the end of June was lower than that of all but two other regular AA shortstops. “Association Averages,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1891: 6; “Foreman Still in It,” Baltimore Sun, June 20, 1891: 6.

11 Sporting Life claimed that “outside of the batteries [Barnie] has but three players who came up to his expectations,” one of whom was Van Haltren, now that he was back in the outfield. Why Ray was an unsuitable shortstop replacement for Van Haltren was likely unrelated to his fielding. During the 10 games that Ray started at shortstop in late June and early July, the Orioles were 5-5, and over 56 chances posted a fielding percentage superior to what Van Haltren had been able to do for the season and virtually identical to what Ray did in 1890 (.893 versus .894). Clearly, Barnie’s issue with Ray as his shortstop was more intangible. “Barnie on the Warpath,” Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1891: 6. Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, August 21, 1891: 4; T.T.T, “That Conference,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1891: 6.

12 Walsh was a so-so hitter, whose fielding percentage topped his Western Association peers in 1890. “Short-Stop Walsh Engaged,” Baltimore Sun, July 28, 1891: 3.

13 The offer from Cedar Rapids was $125 a month, with $75 in advance and his transportation covered. Prior to committing to Cedar Rapids, McGraw gave the Davenport Pilgrims the impression that he would be joining them, was listed as a member of the Rockford Hustlers and was reportedly described by the Joliet Giants as one of their own. His decision to join the Canaries prompted the Davenport (Iowa) Times to skewer him in verse:

We will meet, but we will miss him,

For he wasn’t on the square,

We are yearning to caress him,

With a brick, bat or a chair.

“Base Ball Notes,” Davenport Democrat, April 5, 1891: 1; “Notes,” Davenport Weekly Republican, April 11, 1891: 3; Davenport Times, April 15, 1891: 5.

14 In that game, McGraw’s first as a Canary, he stretched to make a fine one-handed stab of a line drive hit by Anson, and collected one of only five hits allowed by Chicago ace Bill Hutchison. In striking contrast to how major-league fans would later view him, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette gushed that “spectators pronounced him a darling.” In his autobiography, McGraw recalled that after the game Anson “said some nice things about my playing” and asked if McGraw might like to play for him in Chicago someday. “A Fine Game,” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, April 17, 1891: 3; “Foul Tips,” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, April 17, 1891: 3; McGraw, My Thirty Years in Baseball, 46.

15 “Base Ball Notes,” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, August 20, 1891: 4.

16 A week passed between when McGraw signed with Baltimore and his arrival in that city. According to Sporting Life, McGraw didn’t leave Cedar Rapids until the Canaries had secured his replacement. “News, Gossip and Comment,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1891: 9.

17 “Still They Slumber,” Baltimore Sun, August 22, 1891: 6.

18 Though he’d relied on Ray alone at shortstop during the Orioles brief 1890 American Association campaign, Barnie frequently used multiple shortstops during a season. He had nine play there in 1889 and Barnie himself was one of 10 to play shortstop for Baltimore in 1883. T.T.T, “That Conference”; J.A. Williams, “Will Columbus Drop Out?” Sporting Life, August 29, 1891: 7.

19 “A Short Stop Signed at Last,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1891: 6.

20 Baltimore Sun, August 26, 1891: 3.

21 “Beaten By One Run,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, August 27, 1891: 2.

22 Welch’s safe slide into home plate in the 10th inning of the final game of the 1886 “world series,” after a wild pitch by Chicago White Stockings pitcher John Clarkson, gave the American Association St. Louis Browns the title, and earned the Browns winner-take-all gate receipts estimated to be $15,000.

23 Werden’s 20 triples in 1890, while a member of the Toledo Maumees, led the American Association. He went on to twice hit over 40 home runs for the Minneapolis Millers of the Western League, record-setting totals not exceeded until Babe Ruth hit 54 in 1920. Stephen V. Rice, Perry Werden SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Perry-Werden/.

24 McGraw was wearing a uniform last worn by Wise, who was 3 inches taller and 70 pounds heavier. Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Bison Books, 1988), 24.

25 In his autobiography, My Thirty Years in Baseball, McGraw mistakenly recalled that the bases were loaded for his first major-league at-bat. “Orioles Defeat Columbus,” Baltimore Sun, August 27, 1891: 6.

26 Crooks’ 57 stolen bases in 1890 were tops on the Solons and ranked ninth in the American Association. “Orioles Defeat Columbus.”

27 My Thirty Years in Baseball.

28 Duffee earned the nickname for the 16 home runs he hit for the St. Louis Browns in 1889, his rookie season, third-most in the American Association that year.

29 O’Rourke joined the Orioles for the 1892 season. The following season, by then known as Voiceless O’Rourke, he was part of a trade with the Louisville Colonels that brought Hughie Jennings to Baltimore. Hugh Jennings, “Rounding Third,” Buffalo News, December 16, 1925: 37.

30 O’Connell was yet another shortstop acquired by Barnie during the summer of 1891. Last with the Lynn club of the New England League, the 19-year-old O’Connell made his major-league debut at shortstop, while Barnie awaited McGraw’s arrival. Sporting Life remarked that he “hardly belongs to the Association class at present” but charmingly described him as “bubbling over with effervescence.” It’s unclear whether Barnie obtained O’Connell to be his new second baseman all along, or if he was competing with McGraw for the shortstop job. O’Connell’s predecessor at second base, Sam Wise, was released along with pitcher Jersey Bakley, in order to make room for O’Connell and McGraw. T.T.T, “That Conference”; “Baltimore Players Released,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1891: 3.

31 “Orioles Defeat Columbus.”

32 “Baltimores, 6; Columbus, 5,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 27, 1891: 9.

33 “Orioles Defeat Columbus.”

34 “Baltimores, 6; Columbus, 5.”

35 “New Blood Tells,” Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1891: 3.

36 Biographer Charles C. Alexander called McGraw “over his head” in the American Association, frequently out of position, struggling to turn double plays and frequently overthrowing first base. By season’s end the Orioles had used eight different starting shortstops. Outfielder Curt Welch became the eighth when he made the first start of his career at shortstop on September 26. Alexander, John McGraw, 27; “Complete Records,” Boston Globe, October 7, 1891: 5.

37 “Wm. Barnie Resigns,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1891: 6.

38 Van Haltren installed himself in left field during those games, with Walsh and Welch playing shortstop. Despite his struggles there, McGraw compiled a fielding percentage at shortstop that was 57 points higher than Van Haltren’s (.833 versus .776). Ray finished the season with the third highest fielding percentage among Association shortstops (.912). “Complete Records.”

39 “Toughest of the Toughs” was also the title of a biographical segment on McGraw’s early major-league career in Ken Burns’ landmark 1994 documentary miniseries, Baseball. Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 52.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 6

Columbus Solons 5

Union Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.