August 26, 1973: Rangers’ Jim Merritt retires hitters and admits to throwing spitters

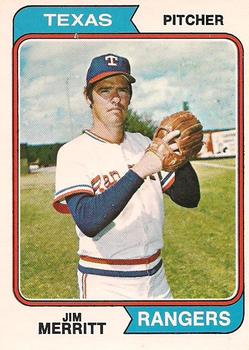

When a team finishes with a 57-105 record, there is rarely a good month to be found in the entire season. The 1973 Texas Rangers, who finished with that precise ledger, plumbed the absolute depths of ineptitude during the month of August, in which they went 6-24. Entering their doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians on August 26, the team had lost 15 of its last 16 games since defeating the New York Yankees in the first game of an August 7 twin bill; the lone win during that span also came at the expense of the Yankees, on August 17 in Arlington, Texas. On this day, the Rangers sent southpaw Jim Merritt to the mound as the sacrificial lamb in the first game, but he ended up pitching a gem that sparked a Texas sweep.

When a team finishes with a 57-105 record, there is rarely a good month to be found in the entire season. The 1973 Texas Rangers, who finished with that precise ledger, plumbed the absolute depths of ineptitude during the month of August, in which they went 6-24. Entering their doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians on August 26, the team had lost 15 of its last 16 games since defeating the New York Yankees in the first game of an August 7 twin bill; the lone win during that span also came at the expense of the Yankees, on August 17 in Arlington, Texas. On this day, the Rangers sent southpaw Jim Merritt to the mound as the sacrificial lamb in the first game, but he ended up pitching a gem that sparked a Texas sweep.

Merritt was a Rangers reclamation project. He had been rescued from the Cincinnati Reds’ scrap heap in the offseason (in exchange for Jim Driscoll and Hal King.) In 1970 the lefty had posted a 20-12 record for the NL champion Reds, but he had also developed tendinitis that was derailing his once-promising career.1 Merritt had lost all four of his August starts and had a 4-9 record with a 4.31 ERA entering the game. Thus, it came as a surprise that he pitched a three-hit shutout against Cleveland, but the reason he later gave for his success came as a complete shock.

Merritt’s mound opponent was Gaylord Perry, author of the just-published book Me and the Spitter, who was struggling through a subpar season on an Indians team that was only slightly less moribund than the Rangers. Perry allowed a leadoff single to Dave Nelson but still set Texas down in order, courtesy of a double play. In the bottom of the inning, Indians leadoff batter Buddy Bell hit a grounder up the line to third baseman Jim Fregosi that should have been an easy out. The normally surehanded Fregosi sailed his throw high over first baseman Jim Spencer’s head and Bell advanced to second. So far, everything that had happened — both in the top and bottom of the inning — was right in line with how the Rangers had been playing.

Then something strange happened. Merritt retired the next three batters, and the Rangers got to Perry for four runs in the top of the second. Nelson struck the last blow in Texas’s onslaught with a two-run double that drove in Larry Biittner and Vic Harris . Merritt threatened to give back a portion of the lead in the bottom of the inning, but a double play helped him to work around the two walks and the double that he allowed and kept the Indians off the scoreboard.

From that point forward, Cleveland never mounted a threat against Merritt for the remainder of the game. Merritt allowed only three additional baserunners — via a walk, single, and double — and retired the side in order in four innings. The Rangers added two more runs off Perry by way of solo homers from Jeff Burroughs in the third and a lead-off shot by Bill Sudakis in the fourth, and Dick Bosman relieved Perry in the top of sixth. Bosman did not fare much better; he allowed a two-run round-tripper to Harris in his first inning of work and a solo shot by Burroughs in the seventh. Jerry Johnson pitched the final two frames for the Tribe and was the only Cleveland hurler to keep the Rangers from scoring.

Texas batters piled up 14 hits in the contest, and numerous batters did damage. Burroughs finished 3-for-4 and knocked out two solo homers; Sudakis had a 2-for-4 line with a double, a home run, a walk, and three runs scored; and Nelson added a 2-for-5 day with two RBIs. Harris outdid them all by going 4-for-4 with a homer, two runs scored, and a team-leading three RBIs in the game.

While all the hitting was both impressive and welcome, Merritt’s shutout became the most noteworthy accomplishment after the pitcher gave a postgame interview in which he claimed to have thrown about 25 or 30 “Gaylord Perry fastballs” during the game. Merritt was asked if he meant a spitball and replied, “You take it from there. We’ve been losing quite a lot of ballgames lately, and I decided to try something new.”2 Merritt claimed, “I talked to Gaylord about it the last time they were in Texas, and he gave me some tips about how to hold the thing.”3

Neither the umpires nor anyone in the Cleveland dugout had suspected anything was amiss during the game, but Merritt continued to hold court about his misdeeds and claimed his teammates knew about it as well. Of Fregosi’s first-inning throwing error, he said, “Jim grabbed the ball on the grease spot and the throw slipped. He told me he wanted that error charged to me.”4

Perry, for his part played it cagey when asked two days later about any role he had played in teaching Merritt the art of the spitter or what role he thought the pitch had played in Merritt’s success against Cleveland. Perry believed that Merritt’s comments were “foolish” and, while he admitted that he had discussed “certain pitches” with Merritt, he declared, “I certainly don’t remember helping him with anything specific. The way I look at it is that it’s so hot in Texas you don’t need to do anything illegal. The sweat keeps the ball plenty wet.”5 Apparently two days was enough time for Perry to forget that the ballgame in question had been played in Cleveland.

One person who did not let any details escape his notice, however, was American League President Joe Cronin. Although the only proof available to Cronin was Merritt’s confession, it was enough for him to fine the pitcher an undisclosed amount. After Cronin informed Merritt of the fine on August 27, the pitcher remained nonchalant and remarked, “I read in a newspaper where the rule says I could have been suspended, or even made to forfeit the game.”6 In light of such possibilities, the fine was not that big of a deal.

Texas manager Whitey Herzog thought the issue was being blown out of proportion and declined to lend credence to Merritt’s spitball comments. Herzog commented, “Because he beat Gaylord, I think Jim was just trying to add a little baloney to the story.”7 Interestingly, Indians general manager Phil Seghi agreed with Herzog. When Seghi was asked about Merritt’s comments and the subsequent fine, he provided keen insight into the situation:

“To be honest with you, I’m inclined to think it was a “put-on” by Merritt. …

“It’s hard for me to believe, and for Joe [Cronin], too, that a pitcher who never has been even suspected of doing anything like that before, suddenly does — and with success. It’s a very difficult pitch to master, you know. It can’t be done overnight.

“I’m not going to get excited about it, although I suppose the next team Merritt pitches against will — which might be what he wanted.”8

Merritt echoed Seghi’s final observation. Asked if he planned to capitalize on spitball suspicions in his next start, he asserted, “Anytime you can make a hitter think, and get him off balance, you’ve got a better chance.”9

Merritt’s confession brought the subject of the spitball’s legality back into discussion. Cronin, during his Hall of Fame career as a shortstop, had faced spitballers who, under the grandfather clause of the 1920 ban of the pitch, were still allowed to use it. Cronin believed that the knuckleball was more difficult to hit and asserted about the spitball, “I’d rather have a guy use it legally than have the connotation of ‘cheater’ pasted on him.”10

Boston lefty Bill “Spaceman” Lee came to Merritt’s defense on August 28 when he too admitted to having thrown spitballs. Lee taunted the American League president as he told the press, “Tell Cronin I threw a spitter in Detroit a while back. … Yes, I have a tube of petroleum jelly in my locker … so tell Cronin he’d better fine me because I was a bad boy.”11 Cronin laughed off Lee’s comments, saying, “I haven’t seen the papers yet but I imagine the club has told him to shut up. He’s a typical left-hander, juicy as they make ’em.”12 Whether Cronin’s choice of the word “juicy” was a pun is up for debate.

Similarly, the question as to whether or not Merritt’s pitches were “juicy” for the remainder of the 1973 season is also up for debate. He failed to win another game all year and finished the season with a 5-13 record. As for the spitball, as of 2019, it remained illegal, so pitchers continue to have to be creative to gain an edge on hitters.

Sources

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CLE/CLE197308261.shtml .

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1973/B08261CLE1973.htm .

Notes

1 Gregory Wolf, “Jim Merritt,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/9f41cc91 , accessed January 14, 2019.

2 “Rangers’ Merritt Fined for ‘Gaylord Fast Balls,’” Corpus Christi (Texas)Caller-Times, August 28, 1973: 19.

3 Randy Galloway, “Home Runs Provide Boost,” Dallas Morning News, August 27, 1973: 4B.

4 Ibid.

5 Randy Galloway, “The Wethead Upset, Too,” Dallas Morning News, August 28, 1973: 3B.

6 Randy Galloway, “Jim Greases Prexy’s Palm,” Dallas Morning News, August 28, 1973: 1B.

7 “Rangers’ Merritt Fined.”

8 “Merritt Remarks Draw Cronin Fine,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 28, 1973: 32

9 “Rangers’ Merritt fined.”

10 Red Smith, “Lee Is as Juicy as They Make ’Em,” New York Times, August 31, 1973: 17.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Texas Rangers 9

Cleveland Indians 0

Game 1, DH

Cleveland Stadium

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.