August 27, 1894: Charlie Bennett Charity Game

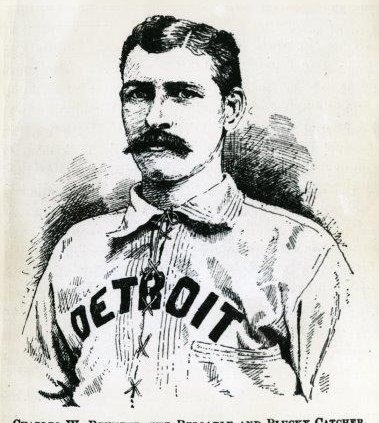

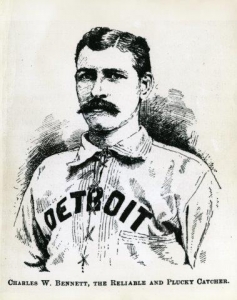

“His hearty ‘glad to see you,’ and the warm grasp of the hand were the same as of old,” wrote the Boston Globe reporter who shook hands with Charlie Bennett. His eyes “twinkled merrily” during the interview at the apartment of Kid Nichols on Tremont Street in Boston.1 But this was not the same Charlie Bennett everyone remembered. The once great catcher had been crippled in January of 1894 when he slipped while boarding a train in Ottawa, Kansas, and was run over,2 losing parts of both legs, requiring double amputation. “Only his strong constitution, made near perfect by his outdoor work and constant training, saved his life,” wrote the Detroit Free Press, which had witnessed his career with the Detroit Wolverines from 1881 to 1888.3

“His hearty ‘glad to see you,’ and the warm grasp of the hand were the same as of old,” wrote the Boston Globe reporter who shook hands with Charlie Bennett. His eyes “twinkled merrily” during the interview at the apartment of Kid Nichols on Tremont Street in Boston.1 But this was not the same Charlie Bennett everyone remembered. The once great catcher had been crippled in January of 1894 when he slipped while boarding a train in Ottawa, Kansas, and was run over,2 losing parts of both legs, requiring double amputation. “Only his strong constitution, made near perfect by his outdoor work and constant training, saved his life,” wrote the Detroit Free Press, which had witnessed his career with the Detroit Wolverines from 1881 to 1888.3

It was now August and Bennett was tired from the long train ride from Michigan, but was able to enjoy some relaxing moments with his wife and former teammates Nichols and Charlie Ganzel and their wives. He had been fitted with artificial limbs in early June4 and was said to simply resemble someone suffering from rheumatism.5 But while this was not the same Charlie Bennett physically, his friends still cherished the time with the old catcher who had “stored away an inexhaustive sic fund of stories of the game and its kings.”6

Bennett was in town as Boston held a charity game on August 27 against a squad of college players. The proceeds were going to Bennett. The Boston Post said tickets for the game were “selling like hot cakes.”7

The former catcher saw 9,000 cheering fans come to pay tribute to him. “It was a trifle too cool for the greatest enjoyment,” wrote Sporting Life, “but it did not deter the friends and admirers of Boston’s crippled catcher from turning out in large numbers.”8 It must have been a moment that those who witnessed it would never forget, as Bennett made his way to his usual position “with the aid of his crutches and artificial limbs,” wrote Tim Murnane in the Boston Globe. “He walked out to the home plate just before the ball game, and there, surrounded by the members of both teams, bowed to the spectators on the bleachers and in the pavilion until the grounds fairly shook with the cheers.”9 He was overcome with emotion, the Boston Daily Advertiser noted, as “his eyes were filled with tears, the corner of his mouth twitched, and his lips trembled with emotion.”10

Gentleman Jim Corbett, the champion boxer of the day, donned the uniform of Boston’s Jack Stivetts (who was away following the death of his father)11 and went out to play left field for the Beaneaters. He was not afraid to get Stivetts’s uniform dirty as he ran the bases and scored a couple of runs. But his biggest contribution of the day came via a $50 check to Bennett while he himself asked for no travel expenses or compensation for his services. “That shows that he isn’t mean,” the Post wrote.12 Some familiar Boston ballplayers of yesteryear were also on hand: John Morrill, Harry Schafer, Art Whitney, George Wright and his brother Sam, and Dupee Shaw. King Kelly, a player-manager in one last hurrah in the minor leagues, sent a telegram showing that his sense of humor was fine: “Bennett can’t play ball, but he can play cricket, as he has stumps. Put us down for $25.”13

The game began at 2:30 P.M., and the crowd roared when Corbett was the first man to the plate. He swung the bat but looked more like a boxer, and struck out against Frank Sexton, formerly of Brown University and now with the New Bedford club.14 Bobby Lowe doubled, Herman Long, Tommy McCarthy, and Tommy Tucker all singled and Boston led 2-0.

The score remained that way until the fourth when the Picked Nine vaulted ahead with four runs. Guys named Upton, Cotter, Ranney, Abbott, and Steere sliced hits off Boston pitcher Harry Staley. Boston fielders were also sloppy as Billy Nash’s throw was wide and Jack Ryan dropped a throw. When the dust settled, the Picked Nine had scored four runs in the third and eight in the fourth, for a surprising 12-2 lead after four.

Boston stormed back to tie the game in the sixth. Had Sexton stayed in the game, Sporting Life believed, the Picked Nine would surely have won the game. But a pitcher named Dowd came in and “the champions didn’t do a thing with him but roll up ten runs.”15 Corbett was hit by a pitch, Long, McCarthy, Tucker, and Nash singled, Jimmy Bannon doubled, and Ryan doubled. Ten runs had scored and suddenly it was a 12-12 game. Boston added one in the seventh, and in the eighth Lowe reached on an error and Frank Connaughton homered. Boston added another in the eighth for a 16-12 lead and the eventual win. The Beaneaters even gave up their turn at bat in the ninth. Boston had scored 14 unanswered runs to get the victory.

When the game ended, the crowd rushed on the field “to get a good look at Bennett.” Bennett had watched the game from a large chair in the grandstand and “the ovation tendered him when some of his friends lifted him to their shoulders nearly took the roof off the structure,” wrote the New York Sun.16

There were more events after the game. Fred Tenney, McCarthy, Nichols, and Bannon competed in races against each other and later Nash and Lowe had throwing competitions. High jumps were also conducted. After the festivities the players retired to the clubhouse, where Duffy and Long served as a reception committee. Refreshments were served,17 and Bennett expressed his gratitude for the day. Mrs. Bennett mentioned, probably quietly to some of the guests, that Charlie had suffered more than he was letting on but had worked hard to look his best on this occasion. “The whole affair was handled in a first-class manner,” Murnane wrote.18

Bennett sent a thank-you letter to the Boston Globe which was published on August 29. In it he thanked everyone in Boston from the players to the fans and sportswriters “who have shown such magnificent generosity to me in my misfortune by giving me so flattering a testimonial.” He added that he “never shall be able to repay the manifold kindnesses which have been showered upon me from all sides.”19

Bennett remained in Boston at the Nichols residence until September 6, then returned to his home in Detroit, where he had many friends, but “not any more than he has right here in Boston,” Murnane wrote.20

It wouldn’t be the last time Bennett would be on the field accepting the applause of a crowd. On April 28, 1896, a new ballpark was opened in Detroit at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull Avenues. Both teams lined up on the field, and the crowd began to cheer. The Detroit Free Press described the scene: “Charley Bennett, the idolized catcher from the palmy days, came out from the stand leaning on the arm of Charley Snyder, who was the star catcher of the American Association in the exciting days of twelve years ago. They walked to the plate and the players reverently doffed their caps.” The ceremonial first pitch was thrown and Charlie caught it “as easily as he could handle one,” the Free Press remarked. “The cannon boomed, the ceremony was over, and cheer after cheer went up for the man whose name the park bears.”21

The ballpark was remodeled and renamed over the years to Navin Field, Briggs Stadium, and eventually Tiger Stadium until its demolition in 1999. But it began as Bennett Park.

Bennett’s name has often appeared on a ballot for SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend voting.22 He wasn’t overlooked that day at the South End Grounds, however, in what the Boston Journal called “a splendid tribute to a ball player whose personal character made him an honor to his calling.”23

Notes

1 “Same Old Charley Bennett,” Boston Globe, August 27, 1894: 2.

2 “Charley Bennett Maimed,” Detroit Free Press, January 11, 1894: 2.

3 “Poor Charley Bennett,” Detroit Free Press, June 23, 1894: 4.

4 “Charley Bennett’s Benefit,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1894: 3.

5 “Same Old Charley Bennett.”

6 “Poor Charley Bennett.”

7 “Baseball Talk,” Boston Post, August 25, 1894: 3.

8 “Bennett’s Benefit,” Sporting Life, September 8, 1894: 6.

9 T.H. Murnane, “Nearly $6,000,” Boston Globe, August 28, 1894: 1.

10 “Nearly 9000 Persons,” Boston Daily Advertiser, August 28, 1894: 8.

11 “Baseball Talk.”

12 “Benefit Big,” Boston Post, August 28, 1894: 3.

13 Ibid.

14 David Nemec, Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball: Biographies of 1, 084 Players, Owners, Managers and Umpires. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 73; Sexton would play all seven games of his major-league career for Boston in 1895.

15 “Bennett’s Benefit.”

16 “Charlie Bennett’s Benefit,” The Sun, August 28, 1894: 4.

17 “Benefit Big.”

18 Ibid.

19 “Charley Bennett’s Thanks,” Boston Globe, August 29, 1894: 1.

20 Murnane.

21 “17 To 2!!” Detroit Free Press, April 29, 1896: 6.

22 In 2015, Bennett was included on the ballot with a brief summary: “Bennett was one of the greatest catchers of the Nineteenth Century, starring for Detroit and Boston of the NL. He was a powerful hitter who often ranked among the leaders in homers and slugging percentage while finishing in the top 10 in bases on balls six times. His defense was stellar and he was a leader on the field.” sabr.org/latest/announcing-finalists-2015-sabr-overlooked-19th-century-base-ball-legend, retrieved January 24, 2017.

23 “Rousing Benefit,” Boston Journal, August 28, 1894: 3.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 16

Picked Nine 12

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.