August 6, 1897: An unusual brawl and a wild ending

As the morning of August 6 dawned, the Boston Beaneaters, losers in the previous day’s contest, enjoyed a slender two-game lead over the Baltimore Orioles. Two strong pitchers, Boston’s

Fred Klobedanz and Baltimore’s Arlie Pond, were facing each other. Each team had lost 27 games to this point in the season, but Boston had won four more games than Baltimore. Given the tightness of the race, this series between the two teams was viewed as crucial to both.

As a result, the Boston fans, some 9,000 strong, were not only entertained by the result; they also had the relatively rare experience of observing two athletic contests for a single admission price – one professional baseball game (in the eyes of some, two distinct games) and one amateur boxing exhibition. Moreover, the name that was as prominent in the headlines of the day as that of any player was that of the umpire, Tom Lynch.

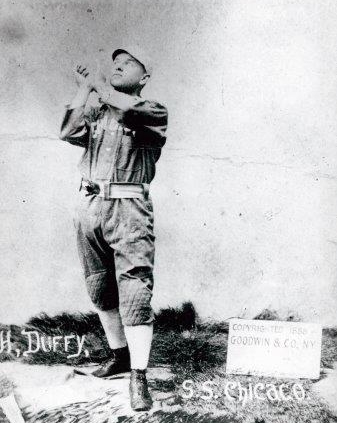

The fact that two distinct games appeared to have been played over the course of the nine innings was evidenced by the box score. Baltimore had all the advantage for the first four innings; the fifth inning served as an intermission of sorts; and Boston held sway from innings six through nine. The game was also entirely differently described in the newspaper accounts. The Boston Globe’s T.H. Murnane touted the excitement of the great come-from-behind victory and Boston left fielder Hugh Duffy’s magnificent throw to cut Baltimore pinch-runner Joe Quinn down at the plate for the final out.1 Baltimore’s scribes, on the other hand, viewed their team as having been robbed by an incompetent umpire who inexplicably chose this day to favor the home team.2

Then came the prizefight at the close of the eighth inning when umpire Lynch, having taken verbal abuse from Baltimore’s Jack Doyle to his limit,3 did the unmentionable and struck Doyle after fining him. This resulted in Doyle striking back, joined by Joe Corbett (heavyweight champion Gentleman Jim’s brother) and a general outpouring of players from both teams until police were able to restore order.

Even after the game was over, the frenzy continued. As the Baltimore team was being driven back to its hotel, the hometown fans followed the horse-drawn coach and pelted it with mud until John McGraw seized a bat, stepped down from the coach, and single-handedly drove the mob away.4

None of this late-inning and postgame excitement could have been predicted at the game’s midpoint, when Baltimore led 5-0. Interestingly, the score could have been far more lopsided in Baltimore’s favor had the Orioles not squandered a golden opportunity in the first. Boston chose to bat first and its half of the inning was unremarkable. McGraw then led off the game for Baltimore with a single. After Willie Keeler popped to shortstop Herman Long, Hughie Jennings took a pitched ball to his hip and reached base. Long then made a great stop in deep short to hold Joe Kelley to an infield hit and prevent McGraw from scoring.

The bases were now full and there was only one out. But Jake Stenzel, swinging at the first pitch, grounded to second baseman Bobby Lowe, who threw quickly to Long, who relayed to first baseman Fred Tenney, completing the double play and denying Baltimore a chance to score.

Boston failed to score again in the second, but Baltimore had better luck in its half of the inning. Pond doubled after Doyle had walked and the Orioles plated two runs on McGraw’s two-out single. The visitors could not add another, however, as McGraw’s aggression backfired when he was caught stealing second. Boston went down in order in the top of the third, but two more Baltimore runs were added in the bottom half of the inning when Keeler reached safely and, after Duffy robbed Jennings of a hit, scored on Kelley’s home run, his second in as many days.

Boston’s offensive futility continued in the fourth, but Baltimore plated its fifth run on McGraw’s fly ball. The Orioles were denied further scoring when Kelley flied out with the bases loaded. Neither team scored in the fifth.

The tide turned in the sixth. Although the Baltimore players had tried to break up Klobedanz by calling him vile names,5 he shut every Oriole batter down over the next four innings except for a bunt single by Pond in the sixth and Jennings’s hit in the ninth.

Meanwhile, Boston scored two runs in the sixth, one in the seventh, and three in the eighth. In the sixth, with Jack Stivetts on third, Tenney on first, and one out, Duffy doubled in Stivetts. Tenney then scored on a fly out but Duffy was stranded at third when Jimmy Collins, who had walked, was erased attempting to steal second in what was described by the Post writer as a “piece of stupid base running.”6

The Baltimore Sun reporter protested that the scoring should never have occurred, claiming Duffy should never have been on base but had reached second “after he had been fairly struck out.”7 Then “Duffy was touched off second by two yards, as admitted by Boston scorers, but was called safe.”8 Neither the Boston Post9 nor Murnane in the Globe said anything at all about the play.10

According to the Sun, these were the first two of five alleged bad calls by umpire Lynch, four before the fight and one after.11 The third disputed call occurred in the seventh when Baltimore claimed that Marty Bergen had hit into a double play. However, Lynch called him safe at first, and Bergen scored on a single by Stivetts.

There was apparently a fourth disputed call but what that may have been was unclear from the Sun’s account. In any case, whether there had been three or four disputed calls to this point is largely irrelevant. According to the Post, “Doyle had been using his tongue to the limit on Lynch all afternoon”12 and continued without letup thereafter until he was ejected.

After the fisticuffs, Jerry Nops relieved Pond, the fans pelted, and almost hit, Kelley with bottles, and Boston went down without scoring, but with maximum excitement.

With two out, Duffy hit safely, stole second, and went to third on the wild throw to second. Then, while Nops was winding up, Duffy had home stolen but lost it when Stahl hit the ball simultaneously for the third out. The last of the ninth presented Baltimore, only one run down, with an opportunity to force extra innings, if not pull out a victory.

With one out, McGraw rapped a sharp grounder to Long and went tearing down the first-base line, smashing viciously into Tenney. Long’s throw rolled to the stands and McGraw took advantage of the situation to make his way to second. Quinn was pressed into service to run for McGraw, who had injured himself on the play. Keeler then weakly fouled out.

At this point, it was all up to Jennings. He did not disappoint, driving Klobedanz’s third offering on a line into left field. There Duffy charged the ball and fired it to Bergen. Quinn had run on contact and the ball and Quinn arrived at home plate simultaneously. This was the final disputed call. Here again, there was no agreement among the scribes. The Boston writers lauded Duffy’s fine throw.13 The Sun and manager Hanlon saw the play quite differently.14

Epilogue

In the aftermath of the game, the plight of the umpires was a main topic in the succeeding week.15 Beaneaters President Arthur Soden indicated that he would have policemen on the ground for the third game between the two teams and that they would be instructed to arrest any ballplayer using profane language.16

Lynch, who had telegraphed his resignation to National League President Nick Young but was convinced to withdraw it by the latter,17 admitted to being in the wrong in striking Doyle first, “but he went so far in his remarks that I simply could not stand it. This was not the first time in the game that he grossly insulted me and I had repeatedly warned him.”18

Murnane clearly sided with Lynch in his reaction: “A deaf and dumb man might not have acted as did Mr. Lynch, but unfortunately deaf and dumb men are not eligible for positions as umpires. If such men as Doyle are allowed to utter foul language with impunity, and to apply obscene epithets to those doing their best to decide plays and balls and strikes as they see them, the time will soon come when no person above the grade of garroter can be secured to umpire a game.”19

From Murnane’s perspective, “Men like Doyle have killed the game in Cleveland, and will in any city they are allowed to live in.”20 But Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon continued to suggest that there was some dishonesty afoot when he was quoted as saying, “[T]his man Lynch is at heart a Boston man, and I know it.”21 He also said, “I know pretty well when a man makes an honest mistake, and I believe this was another case like that of Jack] Sheridan in Cincinnati.”22

Sheridan had resigned at the end of July and umpire Tim Hurst, who had inadvertently harmed a Cincinnati fan with a thrown beer glass on August 4,23 was arrested, charged with assault with intent to kill, and required a writ of habeas corpus to allow him to return to umpiring duties.24 Such was the bleak state of affairs that served as an immediate backdrop to Boston’s victory.25

Notes

1 “Exciting to the Last,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 1,7.

2 “The Baltimore Champions have a reputation for ‘kicking’ at umpires, but not until today have their protests ever ended in blows, although some of the players have at times been struck. Their propensity to object to decisions has been grossly exaggerated all over the League circuit, but it is true that protests from Hanlon’s men are not unusual. Nor is it remarkable that they should protest when they believe that they have all the umpires prejudiced against them. The howl has gone up all over the circuit ever since 1894, ‘Don’t let Baltimore win.’ The howl has been louder this year than ever, and the umpires have given Baltimore unusually rough treatment. Lynch has been one of the very few men on the staff who has heretofore given the Orioles fair treatment. It was all the more surprising that he should suddenly change today and by a series of decisions that seem impossible for a man of Lynch’s judgment, practically snatch from them a game that they had won.” “Fight on the Diamond,” Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6. A more balanced view of the Orioles’ aggressive tactics can be found in Bill Felber, A Game of Brawl; The Orioles, the Beaneaters & the Battle for the 1897 Pennant (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

3 “As Doyle was passing the plate, he began to abuse umpire Lynch. After calling him a vile name Lynch ordered him out of the game. Doyle stood his ground and continued to abuse the umpire loudly enough for people in the stand to hear. Several of the visiting players gathered around the little umpire. Doyle pushed up against Lynch and repeated the vile name three times,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

4 “Disgraceful Fight on the Boston Baseball Grounds,” Boston Post, August 7, 1897: 8.

5 Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

6 Ibid. The stupidity was laid at the feet of Duffy in both Murnane’s account in the Globe and that of the Sun’s reporter, both writers appearing to fault Duffy for his failure to try to steal home on the play. Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7, Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6.

7 Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6.

8 Ibid. This statement about the Boston scorers is not corroborated in any other account.

9 “There was a prolonged kick on calling Duffy safe as the decision was exceedingly close. Jennings and all the hard fighters surrounded Lynch, but it did not faze him,” Boston Post, August 7, 1897: 8.

10 Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 1,7.

11 Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6.

12 Boston Post, August 7, 1897: 8.

13 “The heralded line throws to the plate laid to the credit of Louis Sockalexis, the Indian, of Cleveland, which have been so frequent this season, cannot be compared with Duffy’s throw from left field to the plate, which beat Baltimore in the greatest up-hill fight of the season yesterday afternoon by 6 to 5.” Boston Post, August 7, 1897: 8. According to the Globe’s Murnane, Quinn was out by several feet. Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

14 “Jennings then singled to left field and Quinn crossed the plate, but Lynch called him out and left the field hurriedly. Quinn slid and was lying flat on the plate when he was touched by Bergen, to whom Duffy had thrown the ball. Bergen was standing right behind the plate, and when he reached down, touched Quinn on the chest, almost under his chin. He could not possibly have done so had not Quinn been on the plate.” Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6.

15 “Now for Clean Ball,” Boston Globe, August 8, 1897: 7; “Tough Week for Umpires,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1897: 3. In addition, there were multiple articles and opinion pieces in the August 7, 1897, issue of The Sporting News at pages 1, 4, and 6 and in the August 14, 1897, issue at pages 1, 4, and 5.

16 Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

17 “Now for Clean Ball,” Boston Globe, August 8, 1897: 7.

18 “Lynch’s Statement” Boston Post, August 7, 1897: 8.

19 “Echoes of the Game,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

20 Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7. This is likely a reference to the Cleveland Spiders and their manager, Patsy Tebeau, the notorious reputations of which, collectively, were the equal of those of the Orioles of the period. A flavor of the era can be gleaned from Richard Scheinen, Field of Screams: The Dark Underside of America’s National Pastime (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994), 55-67, and of Tebeau himself at pages 75-79. See also Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 289-292.

21 Boston Globe, August 8, 1897: 7.

22 Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6. This appears to be a reference to a celebrated incident earlier in the year when McGraw was called out at home in a one-run loss to Cincinnati, umpired by Jack Sheridan. “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21, 1897: 2. McGraw was ejected again the following day. In that case, Hanlon had wired to President Young that Sheridan had intentionally robbed Baltimore of the game with Cincinnati and promised to submit affidavits attesting to Sheridan’s bias against Baltimore. Baltimore Sun, May 22, 1897: 6.

23 “Bang!” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 5, 1897: 2.

24 Boston Globe, August 7, 1897: 7.

25 In fact, Young was having such difficulty recruiting umpires at this stage that he resigned his federal clerical position in the office of Auditor for the War Department which he had held for decades so he could devote all his time and energy to his duties as league president, including, in particular, those related to the umpire question. Boston Globe, August 8, 1897: 7; The Sporting News, August 14, 1897: 4.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 6

Baltimore Orioles 5

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.