August 8, 1877: Brown Stockings’ Mike Dorgan wears a catcher’s mask and widespread adoption soon follows

In the first inning of a National League contest on August 8, 1877, Louisville Grays leadoff batter George “Jumbo” Latham fouled off an offering from St. Louis Brown Stockings pitcher Joe Blong. The ball struck catcher John Clapp on the left side of his face.1 His cheekbone was smashed and feared broken, Clapp left the game, replaced by Mike Dorgan, who’d started at shortstop.

In the first inning of a National League contest on August 8, 1877, Louisville Grays leadoff batter George “Jumbo” Latham fouled off an offering from St. Louis Brown Stockings pitcher Joe Blong. The ball struck catcher John Clapp on the left side of his face.1 His cheekbone was smashed and feared broken, Clapp left the game, replaced by Mike Dorgan, who’d started at shortstop.

Clapp, like nearly all catchers of the day, had played without any protective gear on his face, but Dorgan took the field wearing a wire mask.2 At least two catchers had already worn a mask in a regular-season (championship) major-league game: Charley Snyder of the NL Louisville Grays, five weeks earlier on July 3, and Scott Hastings of the Cincinnati Reds on July 21.3 Newspapers were reporting that other catchers had purchased masks and even used them in nonleague games. Still, it was a rare sight.

Why Dorgan elected to wear a mask is uncertain, but a number of factors likely contributed to his decision. Most obviously, the seriousness of Clapp’s injury may have driven Dorgan to better protect his face. He’d filled in for Clapp a handful of times when the Browns’ veteran backstop suffered an injury too severe to go on, but the blow from Latham’s foul tip was the most serious one Clapp had absorbed all year.4

As a 23-year-old rookie, Dorgan may have been more willing to try a newfangled mask than would an older catcher, many of whom considered masks dehumanizing or, even worse, emasculating. A catching injury to his younger brother, Jerry, in late July may have also inspired Dorgan to try using a mask. His ill-fated sibling5 had his lip split open by a foul tip while catching for the Stowe baseball club of central Connecticut. Or perhaps the most substantial factor in Dorgan’s decision was a recent brush with a former foe.

Less than two weeks earlier,6 the Browns had played host to Dorgan’s former and already known-to-be-next team, the Syracuse Stars, members of the new International League. (Dorgan had by then signed a contract to become the Syracuse player-manager in 1878.7) Catching for Syracuse in that game was Pete Hotaling, who’d been recruited along with primary catcher and team captain Dick Higham to replace Dorgan, the Stars’ top producer, and eventually their manager, the year before.8

A few weeks before the Stars-Browns clash, Hotaling had “created quite a sensation” by wearing a mask while catching in a League Alliance game with the Indianapolis Blues.9 The mask was a copy of the as-yet-unpatented wire contraption created by Harvard base-ball team captain Fred Thayer and first worn by Crimson catcher Jim Tyng in collegiate games in the early spring.10

There’s no record of whether Hotaling wore a mask in the St. Louis game, but Dorgan certainly would have been aware of Hotaling’s wearing one in previous games, and might’ve heard the derisive nickname Hotaling’s teammates gave him for wearing it: “Monkey.” It’s plausible that Dorgan got a good look at Hotaling’s mask, which had been custom-made,11 and maybe even borrowed a copy, but it’s more likely Dorgan got his mask for $3 from Peck & Snyder’s of New York, which had begun advertising its new mask in early June.12

St. Louis stood in second place, with two fewer wins than first-place Louisville, when the Grays arrived in the Mound City for a two-game series starting August 7.13 Louisville earned a come-from-behind 4-2 win in the first game of the series, scoring three runs in the top of the ninth, with Joe Gerhardt’s triple to deep left at Grand Avenue Park being the difference-maker.14 Blong took the loss for the Browns, while his batterymate Clapp came away with a split finger.15

The Browns took the field for the Wednesday, August 8, series finale with Clapp back behind the plate but missing two other regulars. Shortstop Davy Force was too ill to play, prompting St. Louis manager George McManus to have Dorgan make his second start of the season at shortstop.16 Center fielder Jack Remsen, out since mid-July with a knee injury,17 was replaced by Tricky Nichols, who’d been the Browns’ primary pitcher through Independence Day. Blong was starting in the box for a 12th straight championship-season game. Opposite Blong was Jim Devlin, the Grays’ only pitcher, making his 38th consecutive start.

As Dorgan donned his mask and replaced Clapp in the bottom of the first, local amateur George Newell trotted out to shortstop, making his one and only major-league appearance. Five “elegant” hits by Louisville along with what the Globe-Democrat called “palpably erroneous” umpiring decisions quickly put the Browns in a five-run hole.18

In the second inning, Blong and Nichols switched positions, McManus’s confidence in the 23-year-old St. Louis native clearly shaken. The Browns clawed two runs closer in the bottom of the second on hits by Art Croft, Joe Battin, and Blong. A trio of St. Louis errors in the fourth gave Louisville another run and a 6-2 lead.

Baserunning calamity marked the Browns’ next turn at bat. First, Herman Dehlman was called out for missing first base on an apparent double to left. Then after singling to center, Dorgan was picked off by catcher Snyder, leaving the home crowd fit to be tied.

Louisville tacked on three unearned runs off Nichols in the sixth on an error by first baseman Dehlman and four hits, the last a triple by Snyder. Sometime during the inning, Gerhardt became sick and was replaced by British-born Art Nichols, believed to be no relation to the Browns pitcher.

The Grays scored their final run in the seventh on a missed catch by 16-year-old reserve Leonidas Lee, covering right field for Dorgan (the Browns’ regular there over the previous three weeks), and an error in judgment by Dorgan, who left home plate uncovered. Anxious to catch a train to Chicago, Louisville skipped its turn at bat in the top of the ninth, but it made no matter. Croft tallied a final run for St. Louis in its last turn at bat, but that was all the home team could muster in its 10-3 defeat.

At the time, Dorgan was believed by some, as repeated in the August 22 Cincinnati Enquirer, to be the first major-league catcher to wear a mask in a regular-season game.19 Modern baseball histories, like The Baseball Chronology, published in 1991, and others that relied on that seminal work, identify Dorgan as first, albeit from a source other than the Enquirer.20

The unattributed claim that Dorgan was first to wear a mask, buried in the Enquirer’s “Notes, News and Miscellany” baseball column, was rejected later in the same column. The Enquirer asserted that “both Snyder and Hastings wore the mask and found it a failure before Dorgan ever saw one.”21

Snyder wore “the Harvard wire-mask” in a game in Cincinnati after suffering a head injury days earlier, but the absence of any further mention of it in game accounts suggests he stopped wearing it soon after.22 Hastings quickly abandoned his mask after first wearing it in a championship match, electing to use only a rubber mouth guard in the Reds’ next game.23

While Dorgan was at best the third backstop to wear a mask in a game that mattered, he can be credited as the first to adopt using one. Unlike Hastings, and apparently Snyder as well, Dorgan continued wearing a mask after his initial experience with it,24 paving the way for his peers to embrace, rather than shrink from, face protection.

One of those peers was Dorgan’s teammate Clapp, whose injury proved to be much less severe than feared; he returned to action two days later without missing a game.25 Limited to playing in the field for a few games, he resumed catching against the Chicago White Stockings on August 17 – wearing a catcher’s mask.26

A week after Dorgan’s masked debut, the Brooklyn Eagle threw down the gauntlet in an editorial calling for professional catchers to wear masks. “Amateur catchers have wisely adopted this valuable invention, and why the professional catchers do not use it is a puzzle,” asserted the anonymous writer. “There are plenty of men in the fraternity brave and courageous enough to face any physical danger, but they lack the moral courage to do many things requiring that virtue, and being afraid to wear the mask is one of them.” Clapp’s facial injury, and another suffered by Louisville’s Snyder, were given as examples of what masks could prevent.27

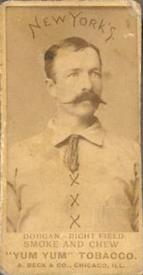

Dorgan, brought to St. Louis for his catching prowess, caught only a handful more games in 1877, and fewer than 20 more over the remainder of his career, which ended in 1890. By that time, mask use was ubiquitous, and Dorgan’s early adoption of the catcher’s mask had faded from baseball’s collective memory. So much so that one obituary penned on Dorgan’s death in 1909 trumpeted how he never wore a mask or chest protector until late in his lengthy career.28

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Peter Morris for providing sources for his identification of Dorgan as the first major leaguer to wear a mask in a regulation game, and Robert Tiemann for providing the contemporary newspaper account of the August 8 game that formed the basis for his entry of Dorgan’s feat into The Baseball Chronology. This article was fact-checked by Laura Peebles and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Peter Morris’s books A Game of Inches (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006) and Catcher (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), John F. Green’s SABR biography of Pete Hotaling, and 1877 St. Louis Brown Stockings game summaries published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He also obtained pertinent material from Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and statscrew.com.

Notes

1 “Broken Up,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 9, 1877: 7.

2 “A Lost Art,” St. Louis Times, August 9, 1877.

3 “The New Cincinnatis,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1877: 5. A remark in a Cincinnati Commercial game summary, uncovered by protoball.org’s Richard Hershberger, confirms that Hastings wore a mask that day against the Boston Red Stockings at the Cincinnati’s Avenue Grounds. Richard Hershberger, “Clipping: The catcher’s mask 3,” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/Clipping:The_catcher%27s_mask_3, accessed August 4, 2023; “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial, July 22, 1877: 4.

4 Dorgan caught his first game of the year for St. Louis on May 22 to allow Clapp’s sore hands to heal; he relieved Clapp during a June 21 contest to again rest his sore hands, and caught on August 4 after Clapp was hit in the jaw the day before in an exhibition game against Indianapolis. “A Tie in Twelve Innings,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 3, 1877: 8.

5 Jerry died at the age of 35 in a Middletown, Connecticut, prison cell from alcohol poisoning after being found drunk in a livery stable the night before. “Base Ball,” Meriden (Connecticut) Republican, July 28, 1877: 3; “World of Sports,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Democrat, June 10, 1891: 4.

6 Coincidentally, it was on July 21, the same day that Hastings wore a facemask in the Cincinnati Reds-Boston Red Stockings game.

7 “Short Stops,” Manitowoc (Wisconsin) Pilot, July 19, 1877: 2.

8 Hotaling was well known to several of the Browns, because he had toiled for the Ilion (New York) Clippers, an amateur team that once fielded Clapp and Latham on their way to the NL. “Matters in Syracuse,” Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1877: 7.

9 “Another Scoop,” Indianapolis Sentinel, July 18, 1877: 8.

10 “Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper, January 27, 1877: 346; “The College Champions for 1877,” New York Clipper, April 14, 1877: 18.

11 According to SABR researcher John F. Green, Hotaling had commissioned the Remington Arms Company of Ilion, New York, for the mask he first used. John F. Green, Pete Hotaling SABR biography, Pete Hotaling – Society for American Baseball Research (sabr.org).

12 “Peck & Snyder’s New B.B. Goods,” New York Clipper, June 2, 1877: 80. It’s ironic that Dorgan might’ve been helped in getting protective gear from Hotaling. In mid-June of 1876, Hotaling, then playing for the amateur Ilion Clippers, barreled into Dorgan at home plate while the then-Stars catcher was waiting for a popup. Hotaling reportedly broke Dorgan’s shoulder on that seemingly dirty play, which at that time was legal. Luckily for Dorgan, his shoulder wasn’t broken, and he returned to the diamond later that month. “Star vs. Ilion,” New York Clipper, July 8, 1876: 117; “Star vs. Brooklyn” New York Clipper, July 15, 1876: 125.

13 Just days before the start of their series, in an ersatz role reversal from those of their namesakes – a canonized French monarch (Saint Louis IX) and another demonized in the French Revolution (Louis XVI) – Louisville’s leading newspaper accused the Browns of baseball heresy. The Louisville Courier-Journal reported a claim from NL umpire Dan Devinney that Browns manager George McManus had recently attempted to bribe him to throw games to be played in Louisville. Before that story broke, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat preemptively countered that Devinney’s bribery claims were “a put-up job,” a “tissuey tale.” One that, according to McManus, was concocted by Grays manager Jack Chapman in retaliation for McManus’s signing of Louisville’s battery of Jim Devlin and Snyder to play for the Browns in 1878. Devinney’s claims went nowhere, eventually lost amid the game-fixing scheme by Grays players that came to be known as the Louisville Scandal. “That Bribery Affair,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 3, 1877: 1; “‘Twas Ever Thus,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 2, 1877: 8; “Summer Sports,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 5, 1877: 7; Daniel Ginsburg, “The 1877 Louisville Grays Scandal,” Road Trips: SABR Convention Journal Articles, 1977, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-1877-louisville-grays-scandal/; “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, November 11, 1877: 8; “A Message to Louisville,” Chicago Tribune, November 25, 1877: 7; “Local Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 19, 1878: 3.

14 “Louisville Luck,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 8, 1877: 8.

15 According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Clapp “stuck to his work like a Major” after getting his finger hurt in the fourth inning, staying behind the plate for the rest of the game.” In A Game of Inches, Peter Morris described Dorgan as recovering from an injury during the August 8 game; however the Globe-Democrat remark, coupled with no mention in St. Louis newspapers of any recent injury to his replacement, suggests it was Clapp and not Dorgan who came into the August 8 contest nursing an injury. “Louisville Luck.”

16 Dorgan also filled in for Force at shortstop on May 19, playing nine innings there against the Chicago White Stockings. The Chicago Tribune summary of that game and accompanying box score both identify Dorgan as playing short. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat account of the game puts Dorgan at shortstop but the accompanying box score shows him in left field. The author’s review of 1877 game accounts identified no other contest in which Dorgan played shortstop. Baseball-Reference.com lists Dorgan as playing only one game at shortstop in 1877, for a total of six innings. It’s unclear whether Globe-Democrat inconsistency is to blame for missing one of his two appearances there. “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, May 20, 1877: 7; “Leather-Hunting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 20, 1877: 7.

17 “Sadly Crippled,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 9, 1877: 8; Chris Rainey, Jack Remsen SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/jack-remsen/.

18 “Sadly Crippled.”

19 “Notes, News and Miscellany,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 1877: 2.

20 The Baseball Chronology contributor Robert Tiemann identified to the author that he relied on an August 9, 1877, game summary in the St. Louis Times as his source for Dorgan’s pioneer status. Author Peter Morris shared with the author that he relied on The Baseball Chronology in crediting Dorgan as the first in his Catcher and A Game of Inches.

21 “Notes, News and Miscellany.”

22 “The New Cincinnatis”; “Beaten by the Bostons,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 29, 1877: 1.

23 “Sky-Larkin’,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 25, 1877: 8.

24 Newspaper summaries of the Brown Stockings’ next game, on August 11, the last caught by Dorgan until mid-September, are silent on his mask-wearing, but several weeks later the New York Sunday Mercury identified Dorgan, and not Hastings or Snyder, as a mask user. Hastings did again wear a mask for an August 21 game in Boston, but his inconsistent use of it told the Sunday Mercury writer that he was not yet an early adopter. New York Sunday Mercury, 2nd edition, September 8, 1877: 7; “Summer Pastimes,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1877: 5.

25 “Sporting Trifles,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 10, 1877: 3.

26 “Pastimes,” Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1877: 5.

27 “The Wire Mask Protection,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1877: 3.

28 That same obituary implausibly asserted that Al Spalding, who played for Harry Wright, “the father of professional baseball[,]” and alongside longtime NL career hits leader Cap Anson, considered Dorgan, a .274 lifetime hitter, “the greatest man on the ball field that ever donned a uniform.” “Michael Dorgan’s Career,” Meriden (Connecticut) Morning Record, May 5, 1909: 3.

Additional Stats

Louisville Grays 10

St. Louis Brown Stockings 3

Grand Avenue Park

St. Louis, MO

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.