July 13, 1965: Senior Circuit takes charge in Minnesota’s first All-Star Game

Several themes were evident for All-Star games played in the 1960s. First was the National League’s crushing superiority during the midsummer classics. Of the 13 games played (two games were played from 1960 through 1962) the National League took 11; the American League won only once (the second game in 1962 was a tie).

Several themes were evident for All-Star games played in the 1960s. First was the National League’s crushing superiority during the midsummer classics. Of the 13 games played (two games were played from 1960 through 1962) the National League took 11; the American League won only once (the second game in 1962 was a tie).

Toward the end of the decade another development, the overwhelming dominance of pitching, manifested itself. Successive scores of 2-1, 2-1, and 1-0 from 1966 through 1968 reflected regular-season play where the equilibrium between hitting and pitching had gone out of balance.1

Another factor, born of expansion, was that new facilities and venues influenced the selection of where games took place. While venerated ballparks such as Fenway Park and Wrigley Field hosted contests, baseball’s hierarchy determined it prudent to showcase recently built stadiums, too. New facilities for the expansion Houston Astros, New York Mets, Los Angeles Angels, and Washington Senators were the site of All-Star contests.2 Older franchises with new stadiums were chosen as well: San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 1961 and Busch Stadium in 1966. A true anomaly took place in 1965 when the Minnesota Twins’ Metropolitan Stadium became the site for the 36th contest. Neither the franchise nor the ballpark was new.

Metropolitan Stadium (“The Met”) was nine years old, originally built for the minor-league Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. The Minnesota Twins franchise had shifted from Washington after the 1960 season, after being in the nation’s capital since 1901. That Minneapolis was a new location for the majors helped lure the All-Star Game to the Twin Cities. Twins president Calvin Griffith’s determination to make sure his club was duly recognized ensured that the game would take place in Minnesota. He had campaigned for Minnesota to host the game almost as soon as his team moved west. According to The Sporting News, Griffith was almost successful in 1963, when at the last moment Cleveland gained selection.3 Undeterred, Griffith continued his quest and because of that persistence he gained approval for the game to take place in Minnesota in 1965.

Griffith had several tasks before him. The seating capacity of the Met was substandard. Construction of double-deck bleachers down the left-field line increased the capacity from 40,000 to 45,000.4 The Minnesota Vikings of the NFL paid the bill and received terms for lower rent in return.5 The seats would be completed mere days before the All-Star Game.6 Griffith also undertook another enterprise, working with Twin City officials and business interests to ensure that visiting baseball fans and officials would get a favorable impression of the Twin Cities. This endeavor took on a life of its own, requiring a great deal of effort in the area of public relations.

The team itself unexpectedly boosted local interest in the All-Star Game. Pegged by many to finish fifth in 1965, the Twins got off to a quick start and by the end of April they and the Cleveland Indians were tied for first.7 Starting pitcher Jim “Mudcat” Grant and veteran relievers Johnny Klippstein and Al Worthington, acquired at midseason the previous year, bolstered the staff. Future Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew and the 1964 batting champion, Tony Oliva, led a potent offense. (Oliva would repeat in 1965.) Two off-field acquisitions also proved key to the team’s success. Johnny Sain, perhaps the best pitching coach in the game, joined the club, as did Billy Martin. Martin’s fiery style contributed toward a more aggressive baserunning game. Manager Sam Mele ably molded the players into a cohesive unit that played to its full potential.

On July 5, after being near the top of the standings all season, the Twins climbed back into first place and held the lead from then on. The following Sunday, July 11, Minnesota faced the New York Yankees, their last game before the All-Star break. The Yankees were in sixth place, 13½ games out, but their reputation (they had won the pennant the five previous seasons) was such that many felt they still had the ability to charge back into contention. Playing at the Met, where Griffith’s project to add bleacher seats had been completed just two days before, Minnesota went into the bottom of the ninth down 5-4. With a runner on, two outs, and two strikes on Killebrew, he blasted a game-winning home run into the left-field seats. The blow proved fatal to New York, and confirmed the Twins as the team to beat. Two days later the 36th All-Star Game took place.

Griffith not only got the bleachers completed on time, his efforts to engage Minnesotans in the process of welcoming baseball to the state also came to fruition. Governor Karl Rolvaag and fellow citizens went out of their way to make visitors to the state feel welcomed. Local businessmen donated golf shirts, dinnerware and briefcases to guests and newsmen. Women received Betty Crocker cookbooks.8 A smorgasbord was scheduled at the Met on the day of the game featuring over 120 local delicacies, including mooseburgers and roast pheasant.9 Griffith had the pool at baseball’s lodging headquarters stocked with fish and made sure visiting officials were provided with poles to catch them.10

Fans began gathering outside the stadium the night before the game hoping to obtain standing-room tickets, which would go on sale noon. Their wait included weathering a passing rainstorm that gradually gave way to morning clouds, which cleared just before game time.11 Griffith’s efforts to generate enthusiasm worked; an over-capacity crowd of 46,709 fans showed up to watch the game.

An underlying drama of the game was that after 35 contests (including the 1961 tie) each league had won 17 games. This development would have been largely unimagined after the 1949 All-Star Game, at which point the American League held a 12-4 advantage over the senior circuit. The tide began to turn in 1950 when the Cardinals’ Red Schoendienst hit a 14th-inning home run for a 4-3 come-from-behind NL victory. The momentum carried forward as the National League proceeded to win 12 of the next 18 contests.

Of key importance in this surge of victories was the National League’s early embrace of black players. Aaron, Banks, Campanella, Clemente, Marichal, Mays, Newcombe, Robinson (Frank and Jackie), and others more than outnumbered their American League counterparts, who for much of the 1950s largely consisted of Larry Doby and Minnie Minoso, only gradually increasing as the 1960s began.12 This imbalance of black talent at the All-Star Game in favor of the National League would prove telling in the game at Minnesota.

Managers for each league did not come to their selection through the traditional process, that of having led the previous year’s World Series representatives. Johnny Keane, manager of the World Series champion St. Louis Cardinals, had resigned after winning the Series. The Yankees at season’s end had fired his counterpart, Yogi Berra. In their place, Philadelphia’s Gene Mauch and White Sox skipper Al Lopez, who had guided their teams to second-place finishes in 1964, led the squads.

Twins fans not only boasted of their first-place club but also crowed that Minnesota had more players on the squad than any other American League team as Lopez added Jim Grant, Jimmie Hall, Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, and Zoilo Versalles to the roster. Twins catcher Earl Battey started at catcher; he was selected by a poll of players, managers, and coaches for that honor. Minnesota’s Mele and coach Hal Naragon were members of the coaching staff. Twins reliever Bill Pleis was called on to throw batting practice on a field where the infield foul lines were colored red, white, and blue, and then white to the fences. Bases were red, white, and blue and the fungo-hitting circles contained red, white, and blue stars.13

Charley Johnson, sports editor of the Minnesota Star and Tribune, threw out the first pitch. He was a significant force in drumming up support to build Metropolitan Stadium and then later succeed in bringing major-league baseball to Minnesota. Johnson and the rest of the folks at the game did not have to wait long for the fireworks to begin.

A major attraction of the game for Minnesotans besides having a chance to see their local favorites play was the opportunity to view the National League stars, none of whom shined brighter than San Francisco Giant Willie Mays. Mays had played for the Millers in 1951. He was hitting a torrid .477 when called up to the Giants, much to the unhappiness of resident fans. The outcry at his being taken from the Millers was so great that Giants owner Horace Stoneham found it necessary to buy ads in Minneapolis newspapers apologizing for taking the gifted outfielder from their midst.

Mays, as usual, was having a great season. Leading the majors in home runs with 23 and batting at .339, he had just passed Stan Musial in career home runs with his 476th, placing him sixth on the all-time list. In the last game before the All-Star break, however, he and catcher Pat Corrales of the Phillies had collided in a bone-jarring play at the plate, and both players had to be from the game. There was legitimate concern that Mays might not be able to play.14

Mays did indeed play, and batting leadoff, promptly reminded Minnesotans why Stoneham had brought him to the majors 14 years earlier. On the second pitch of the game from Orioles starter Milt Pappas, Mays ripped a 415-foot home run into the left-field pavilion.15 Musial was dinged once again; Mays’s homer was his 21st hit in All-Star Game competition, breaking a tie with the St. Louis Cardinals great.

Mays’s homer was just the initial blow. With two outs and Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell on first, the Braves’ Joe Torre launched a home run, barely fair, into the left-field pavilion to make the score 3-0 against a stunned American League. Pappas gave way in the second to Minnesota’s Grant, who at 9-2 was in the midst of his best season. Grant was as unsuccessful at holding the National League at bay as Pappas. Willie Stargell came to bat with a runner on third and homered into the right-field bullpen, making the score 5-0.

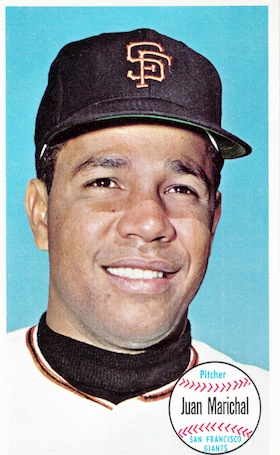

Meanwhile, the almost effortless pitching of San Francisco’s Juan Marichal shut down the American League through the first three innings. He faced the minimum nine batters; Cleveland’s Vic Davalillo’s single in the third was erased when Battey grounded into a double play. Marichal, having pitched the maximum three innings allowed in the All-Star Game, gave way to Cincinnati’s Jim Maloney to start the bottom of the fourth.

Maloney gave up one run that inning and was on the verge of getting through the fifth when disaster struck. With two outs, he walked Hall. Detroit’s Dick McAuliffe homered over the center-field fence. Mays injured his hip when he slammed into the fence in an unsuccessful attempt to catch McAuliffe’s drive but stayed in the game, a key development as it turned out. Brooks Robinson beat out an infield hit, which brought Killebrew to the plate. Having thrilled Twins fans with his game-winning homer over the Yankees two days before, he brought them out of their seats again, connecting off Maloney for a game-tying homer into the left-field pavilion. Maloney departed after allowing five runs in 1⅔ innings. It proved the only All-Star Game appearance of his career.

The game remained tied until the top of the seventh. Once again Mays proved to be the catalyst. Leading off, he drew a walk off Cleveland’s Sam McDowell and advanced to third on Hank Aaron’s single. Cubs third baseman Ron Santo came to bat and chopped the ball up the middle. Shortstop Versalles corralled the high chopper but there was no chance to get Mays at home or Santo at first. It proved to be the game-winning hit. (Santo had joked just the day before, “As a .258 hitter, I felt I was pretty much on the squad on a rain check.”16) Mays’s 17th run, the most in All-Star Game competition, merely extended a record he already held.17

There would be one more moment of drama. Versalles walked with two outs in the bottom of the eighth and moved to third on a single by Tigers catcher Bill Freehan, who took second on Mays’s throw to third. Hall came to bat, Twins fans willing him to win the game. He flied to deep center, where Mays would normally have caught the ball with little effort, except that on contact Mays appeared to misjudge the ball. Recovering, he leaped to make a backhand catch, ending the inning. After the game he said, “I slipped as I started to go back. I was scared to death.”18

Tony Oliva doubled to lead off the ninth, giving Twins fans hope for a rally, but Bob Gibson finished off the inning, getting the last two outs on strikeouts.

Sandy Koufax, who was pitching when Santo drove in the deciding run, got the win. Marichal edged out Mays for the Most Valuable Player of the game with his three innings of shutout ball, but the big news was that the National League had edged ahead of the American League in wins for the first time since the games began in 1933. As of 2014, their lead remains intact.

Killebrew’s home run represented a consolation prize of sorts for Twins fans; however, an even greater reward awaited them on September 26, when the Twins beat the Washington Senators, 2-1, to clinch the pennant.

The All-Star Game represented Minnesota’s ability to support major-league baseball; the Twins’ triumph represented their ability to play better than anyone else did in the American League that year. Twenty years later the All-Star Game took place at the Metrodome and in 2014, the 85th summer classic (including two ties) took place at Target Field. Minnesota subsequently won two pennants and two World Series championships after their encounter with the Dodgers. While these contests generated tremendous excitement, they could not recapture the first-time thrill of watching baseball’s finest in July 1965 or the continuing pleasure of the locals achieving an unexpected pennant.

This article originally appeared in “A Pennant for the Twin Cities: The 1965 Minnesota Twins” (SABR, 2015), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Notes

1 Which it was. After the 1968 season, which saw a combined major-league batting average of .237, the pitching mound was lowered and the strike zone reduced in size, restoring a semblance of offense to the game.

2 Washington hosted the All Star Game twice in the 1960s – first in 1963 then in 1969, the latter driven in part by the celebration of professional baseball’s centennial.

3 “Minnesota Has Reason to Be Proud,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1965, 14.

4 Minnesota.twins.mlb.com/min/ballpark/min_ballpark_metropolitan_stadium.jsp

5 Jim Thielman, Cool of the Evening, The 1965 Minnesota Twins (Minneapolis: Karl House Publishers, 2005), 73.

6 “Twin Bleachers Completion Now Scheduled for July 9,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1965, 20.

7 “Yanks, Phils Picked By Writers, Fans,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1965, 1.

8 “Twin Cities Twinkles,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1965, 8.

9 “Hungry for Mooseburger? It Was on All-Star Menu,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1965, 5.

10 Thielman, 207.

11 “Twin Cities Twinkles,” 8; “Juan ‘n’ Willie Set N.L. Stars Winking,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1965, 5.

12 The Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers did not even integrate their teams until the late 1950s and even then only with marginal utility players.

13 “Twin Cities Twinkles,” 6.

14 James Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 430-431.

15 “Juan ‘n’ Willie.” In a move designed to give Mays and Hank Aaron more at-bats, Mauch unconventionally placed them first and second in the batting order.

16 “Twin Cities Twinkles,” 8.

17 “Juan ‘n’ Willie.”

18 “Juan ‘n’ Willie.”

Additional Stats

National League 6

American League 5

Metropolitan Stadium

Bloomington, MN

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.