June 20, 1894: Congress Street’s glorious finale

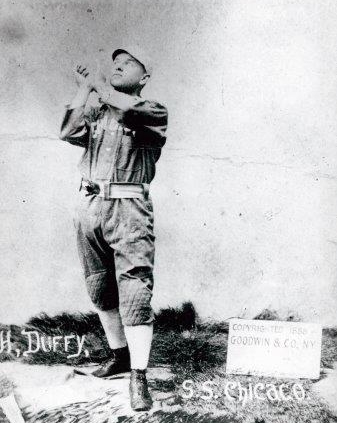

Hugh Duffy strode to home plate in the bottom of the ninth inning. His Bostons trailed 12-11 but Bobby Lowe stood on third and Herman Long was on second after his clutch double. It was another roller-coaster thrill ride for the 2,100 fans in attendance but this was special, as it would be the last official National League game to be played at the Congress Street Grounds.

Hugh Duffy strode to home plate in the bottom of the ninth inning. His Bostons trailed 12-11 but Bobby Lowe stood on third and Herman Long was on second after his clutch double. It was another roller-coaster thrill ride for the 2,100 fans in attendance but this was special, as it would be the last official National League game to be played at the Congress Street Grounds.

The Beaneaters had rented the old home ballyard of the champ Players’ League Reds (1890, home 48-21) and champ American Association Reds (1891, 51-17) because their magnificent South End Grounds was turned into ashes on May 15 along with 200 other Roxbury structures. Reborn over one hectic weekend and improved during the subsequent four weeks of play, the neglected winningest park in Boston baseball history (.726) was brought back to useful life for Hub fans, but the end was two outs away.

Appropriately, the much-despised Baltimore Orioles were the opposition on Wednesday, June 20, 1894. Ned Hanlon’s crew was the opponent when the conflagration occurred and they were now in first place, looking to dethrone the three-time NL champion Beaneaters. Baltimore (30-11) was considered an upstart adversary to Boston (31-17).

Rehabbed Congress Street had the second double-decked grandstand in Boston; the multi-witch-hat towered South End Grounds Pavilion (1888) was the first. When Boston Wharf Co. architect Morton D. Safford was contracted to design a PL facility, the SEG II was the natural model for it. In addition, the Congress Street locale was downtown, near Boston Harbor, nearly four miles away from the annoying sooty railroad smoke at Berlin and Walpole Streets. Because of short distances down both lines (250 to 275 feet), it was a hitter’s heaven and a hurler’s hell.

Through 26 post-fire games, Boston’s record there was 19-7; they averaged almost 11 runs per contest but allowed 9. During the monthlong span, Boston had clobbered Cincinnati 20-11 on May 30, behind Lowe’s record four home runs, and pasted Baltimore, 24-7, on June 18. Not immune themselves, the hosts fell 22-8 to Cleveland Spiders star Cy Young on June 1 and were humiliated, 27-11, by Pittsburgh on June 6 when desperation substitute pitchers Henry Lampe and Tom Smith failed terribly by allowing seven Pirates fence clouts in one afternoon.

Some aspects adding to the ninth-inning drama on June 20 evolved from previous episodes. The starters were John “Sadie” McMahon for Baltimore and “Happy Jack” Stivetts for the locals. They had history, especially within the 1891 AA season. Jack was with St. Louis and McMahon with Baltimore before it was absorbed by the NL in 1892. They were two of the stellar workhorses of the Association’s final campaign, McMahon topped the doomed circuit with 35 wins, Stivetts amassed 33 (third). They were one-two in appearances and games started, McMahon threw 503 innings (most). Stivetts led the AA in both walks and strikeouts, and despite his being near the top in hits and runs given up, McMahon’s 2.81 ERA was fourth-best. Delaware native McMahon led the AA with 36 victories in 1890.

Now in 1894, Stivetts lost to McMahon in April in Baltimore. Sadie also beat Charlie “Kid” Nichols twice, the day before the fire (last victory recorded at the South End Grounds II) and just two days before the epic in progress. Nichols had an 8-0 record at Congress Street before the 9-7 defeat. Stivetts won the season opener at SEG II easily over Brooklyn and then was just horrible, losing eight straight (allowing 96 runs), before rebounding by winning four. On June 1 he had eight of the Beaneaters’ 12 losses. Meanwhile, McMahon was cruising at 12-3, winning 10 of his last 11 starts.

This was the sixth and last game in Boston between the rivals and Baltimore had won three of the five. Up to that date, McMahon was 5-3 lifetime at Congress and Stivetts had a 7-5 mark. Jack’s four wins there in 1894 were backed by 66 Beaneater tallies.

Few fans outside of the Fort McHenry area liked the rude, crude, rough-and-tumble style of Orioles play led by belligerent John McGraw and his instigator pal Hughie Jennings. So every game soon became a ferocious grudge match. Congress Street’s swan song seemed lost after seven innings with Sadie ahead 7-5, in what was a near pitcher’s duel at the harborside launching pad. The daily slugfest had not begun – yet. Second batter Herman Long (four hits) smacked a home run in the first but Baltimore took hold of the game in the third frame with four runs and added two more in the fourth.

In the eighth McMahon suddenly lost his stuff completely and Boston smacked five hits, including Tommy McCarthy’s bases-clearing double (of his four hits), to surge ahead, 10-7. The crowd was ecstatic but Happy Jack instantly turned into April-May Jack and “lost his nerve and went to pieces.”1

After a Long fumble (ruled a hit), a second Dan Brouthers double to go with his triple that day, a hit batsman, and two walks, two runs had scored and the bases were still packed. Beaneaters manager Frank Selee had seen enough and with captain Billy Nash called on Tom Lovett to relieve. Lovett was 5-1 at Congress Street, but was bedraggled by fatigue. His first pitch short-hopped the plate and rolled to the backstop fence, allowing two runs. Then Wilbert Robinson’s flyout brought home Jennings. On two hits the Orioles had gone ahead 12-10. Lovett steadied and got two more flies, ending the rally.

Catcher Jack Ryan grounded out to start the bottom of the ninth. Things looked bleak but local boy Frank Connaughton batted for Lovett and check-swung on what should have been a third strike. Umpire Bob Emslie allowed him to walk to first. The pesky old gal of a ballyard had set the stage, she was not about to host a sad finale. Then NL home run leader (13) Bobby Lowe, who had belted one off McMahon two days before, doubled, and according to only the Boston Herald, scored Connaughton.

Many in the depressed crowd heading to the exits stopped cold and turned instantly into a screaming mob as Long, who also crushed a McMahon pitch two days previous, as well as in the first inning, also doubled. To make sure the sharp hit was not caught, Lowe hesitated going to third and did not score. This is where the other newspapers had Connaughton reach home. In any case it was 12-11.

Up came Duffy. Thus far he had only an infield single but had launched two home runs the day before off Bill Hawke, another Delaware-born Oriole, in Boston’s 13-8 loss. Back in April 1891 as a member of the AA champ Reds, Duffy lofted a McMahon ninth-inning toss into the left-field seats, but McMahon had a comfy 12-5 lead that afternoon.

This time the situation was a bit more intense. McCarthy, the other “Heavenly Twin,” was on deck with four hits already so McMahon decided to pitch to Duffy. His smooth swing put the ball into the air and eventually it drifted into the left-field bleachers. Game over at 13-12. Some members of the crowd swarmed the field and carried Duffy around the infield while others gleefully cursed the shocked, exiting Orioles. The short-lived Congress Street Grounds encore had gone dark on its own terms of grandeur.

The Beaneaters would then leave town on a monthlong road trip enabling carpenters to continue to rebuild, at much less cost and minus any ornate design, the SEG III along what was a straightened and lengthened Columbus Avenue. Familiar Berlin Street was erased from all maps.

For ticket holders of the historic game just ended, it would be a great memory, but for twentieth- and twenty-first-century researchers the game’s scorebook outcome is a little frustrating.

Because of the rules of the day, Duffy was not officially awarded a home run, a second run scored or an RBI beyond Long’s touching of home plate. The Boston Globe, Post and Journal each gave him a box-score single, while the Daily Advertiser and Herald gave the hero a double in their boxes. Most headlines exclaimed that he hit a “home run.”2 The Baltimore Sun listed a round-tripper in its box for Duffy along with a second run scored but it took a definite run away from Lowe to keep the tally at 13. The New York Clipper told of the home run in text but did not include it or any double in its stat box.

The Herald was very meticulous in detail about the whole game and was the only paper to briefly explain the final scoring. “Although Duffy’s hit was a home run, he gets credit under the rules for a two-baser only, as only that was necessary to send in the run that won the game.”3 The box score followed. The Globe reported that Duffy had stopped at second, likely knowing the rule and because he was surrounded by the celebrating mob who stopped his progress halfway around the bases.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the following newspapers: Boston Globe, Boston Post, Boston Courier, Boston Advertiser, Baltimore Sun, and New York Clipper.

Notes

1 Tim Murnane, “Duffy’s Homer,” Boston Globe, June 21, 1894: 2.

2 See, for instance, “Duffy’s Home Run,” Boston Journal, June 21, 1894: 3.

3 Boston Herald, June 21, 1894.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 13

Baltimore Orioles 12

Congress Street Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.