June 28, 1902: Little Napoleon vs. the Czar: John McGraw suspended by Ban Johnson after outburst

On a gloomy afternoon, more than 3,000 fans settled down in American League Park.1 The forecast for June 28, 1902, called for rain. But clashing personalities, not weather, ended the game early.

On a gloomy afternoon, more than 3,000 fans settled down in American League Park.1 The forecast for June 28, 1902, called for rain. But clashing personalities, not weather, ended the game early.

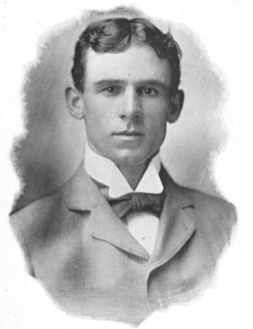

Little Napoleon

The new Orioles had been a franchise only since 1901, when they finished three games over .500 but were still 13½ games out of first place. The 1902 season was worse; they were 26-30 before this game was played. The team finished in last place.

Managing the Orioles was the pugnacious “Little Napoleon,” John McGraw. As a player with the old Baltimore Orioles, McGraw was one of the best leadoff men of the era. He batted .320 for nine consecutive years, led the league in runs scored and walks, and stole 436 bases. He and the Orioles won three National League pennants in a row from 1894 through 1896. But they, and McGraw, were known more for a strategy of cheap tricks and intimidation.

The early Orioles (1882-1899) were infamous for nasty play, and McGraw was one of their nastiest players. They held onto runners by their pants loops, spiked basemen, and notoriously baited, insulted, and belittled umpires.

“Our Baltimore club had a reputation as umpire fighters,” McGraw remembered. “I guess we did make life pretty miserable for some of them. … It was our second nature to fight for the smallest point, and as a consequence, the umpires often had to take the brunt of our wrath.”2

“The Orioles,” remembered former umpire and National League President John Heydler, “were mean, vicious, ready at any time to maim a rival player or umpire if it helped their cause. The things they would say to an umpire were unbelievably vile, and they broke the spirits of some fine men.”3

The Czar

The National League contracted from 12 to eight teams in 1900, disbanding Baltimore’s franchise. Western League President Ban Johnson saw an opportunity and relocated his teams to the vacated cities. He renamed his operation the American League and declared it equal to the National League, whose players he stole, enticing them with more lucrative contracts.4 McGraw agreed to be a player-manager for the new Baltimore club and insisted on having an ownership stake in the team. Johnson accepted the terms.5

Johnson’s reputation for totalitarian control of the American League earned him the nickname of “Czar.”6 He detested rowdyism, promising more wholesome play to attract fans. He supported his umpires’ decisions and quickly suspended players who acted out. “My determination was to pattern baseball in the new league along the lines of scholastic contests, to make ability and brains and clean, honorable play, not swinging of clenched fists, coarse oath, riots or assaults upon the umpires decide the issue.”7 Johnson’s baseball was not the game McGraw played.

After Johnson directed a series of suspensions and fines against the Orioles, McGraw suspected that he was targeting Baltimore’s team. “As President of the American League, [Johnson] was constantly picking on the Baltimore club,” McGraw asserted. “Setting me down for frequent suspensions and frequently disciplining other players. His severity was unusual and unjust, I thought. This crippled us considerably.”8

Tensions came to a head on June 28, 1902.

The Rundown

Tommy Connolly umpired the game, the first of a two-game series against the Boston Americans. Connolly and the Orioles had a history: In 1901, he ruled that McGraw had interfered with a runner and allowed the run to score. That day, Connolly needed a police escort to leave the field.9

Joe McGinnity took the hill for Baltimore, and Cy Young for Boston. McGraw was in the lineup at third base for the first time in five weeks after being spiked in the knee in Detroit.10

Before the fifth inning, McGinnity was in control, allowing only one run on five hits. Meanwhile, whatever residual pain may have been in McGraw’s knee didn’t affect him at the plate. He led off the game with a triple and scored when center fielder Joe Kelly got a base hit. In the seventh McGraw bunted for a hit, stole second, and reached third on an error. The Orioles had a three-run lead going into the sixth inning. But Cy Young limited the damage and kept Boston in the game long enough for the wheels to come off McGinnity.11

In the sixth, Boston manager-third baseman Jimmy Collins hit a single. Center fielder Chick Stahl followed with a double. Buck Freeman, who would lead the league in RBIs in 1902, drove them both home. After McGinnity secured two outs, Freddy Parent singled and was driven in by Lou Criger’s double.

McGraw tried to stop the bleeding in the seventh by giving the ball to right-hander Jack Cronin. Cronin walked left fielder Patsy Dougherty, Collins got another hit, and both men were driven in when Stahl hit a triple. It was 8-4, Boston.

Then came the eighth inning.

With Baltimore at the plate, first baseman Dan McGann lined a base hit into center field. Next came an infield hit by Cy Seymour. Young tried to hold McGann on second base but overthrew the ball past the defender, allowing both runners to advance.

Baltimore utility catcher Roger Bresnahan followed with a grounder on the third-base side. With McGann on third, Seymour on second, and Bresnahan on his way to first, McGann broke for the plate. With no one out, if Collins opted to take the sure out at first, McGann would score a run. However, if McGann could sustain a rundown between Collins and Boston catcher Criger, Bresnahan would make it to first safely and Seymour would be able to advance on the play.

“We always took chances,” McGraw later remembered. “There is always an advantage in taking those chances. It puts the other fellow in the worry about what to do.”12

A Pair of Suspenders

Few in the audience paid attention to what the other runners were doing. While everyone watched Collins and Criger try to catch McGann, Seymour went to third.13

Seeing that Bresnahan had made it to first safely, McGann broke back for third and Seymour retreated for second. McGann slid safely into third. For a brief moment, the Orioles had the bases loaded with no one out.14

Quickly, Boston shortstop Freddy Parent called for the ball and tagged Seymour on second base, arguing to Connolly, the umpire, that Seymour had run past third but failed to retouch it when he ran back to second. Connolly agreed and called Seymour out. McGraw ran out to argue.15

The Baltimore Sun insisted that “McGraw did not talk roughly to the umpire, nor was he as strenuous as he has been on numerous occasions this year when he was not penalized.”16 The Boston Globe, on the other hand, insinuated that McGraw threatened to hang Connolly.

Whatever was said, Connolly ejected McGraw, but the Baltimore manager refused to go. The umpire then declared the game a forfeit to Boston.

The Globe insisted that it was fortunate that the police were on the scene to protect the players and Connolly from the “enraged” Baltimore fans.

Ban Johnson suspended McGraw two days later. “I am convinced Umpire Connolly was absolutely right,” he stated. “He knew what he was doing and because he knew the rules, I am glad he maintained his position and humiliated Mr. McGraw.”17

McGraw was not surprised to hear the news: “Ban is a great suspender. Why, he’s almost a pair of suspenders.”18

“Johnson is down on Baltimore and would like to see it off the map,” McGraw said during the suspension. “I am sick and tired of the whole business and I don’t care if I never play in the American League again.”19 McGraw left the Orioles, going to the Giants, promising on record not to tamper with the Baltimore club on his way out.20

However, Joe Kelly and McGraw sold their ownership of the Orioles to Kelly’s father-in-law, Sonny Mahon. Mahon turned around and sold those holdings to the Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants. Immediately, both clubs began transferring talent from Baltimore to their respective clubs. By July 17, Baltimore was unable to field a team against St. Louis and was forced to forfeit its second game in 15 days.21

The next year, Ban Johnson moved the Orioles to New York, where they would later become the Yankees. Although the Yankees eventually came to dominate the sport, for nearly two decades the Giants would be Gotham’s main attraction.

Winning 10 pennants and three World Series, the Giants led New York baseball in attendance for 15 of the next 20 years.22 Only in 1920, with the help of Babe Ruth, did the Yankees consistently surpass their crosstown rivals in popularity.

McGraw and the Giants faced the Yankees in the 1921 World Series. He welcomed the team that was once his Baltimore Orioles to the big stage by beating them five games to three.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Forfeited to Boston,” Baltimore Sun, June 29, 1902.

2 John McGraw, My Thirty Years in Baseball (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923), 78.

3 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 55.

4 Joe Santry and Cindy Thomson, “Ban Johnson,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/dabf79f8, accessed November 15, 2019.

5 Alexander, 77.

6 “M’Graw and Johnson: Talk of Trouble Being Fomented by American League’s Enemies,” Baltimore Sun, July 29, 1901.

7 Frank Menke, “Life of Ban Johnson,” installment number 1, quoted in Eugene C. Murdock, Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1982), 39.

8 McGraw, 130.

9 “Make a Poor Start,” Baltimore Sun, August 16, 1901.

10 “‘Mugsy’s Way,” Boston Globe, June 29, 1902.

11 “Forfeited to Boston.”

12 McGraw, 88.

13 “Forfeited to Boston.”

14 “Forfeited to Boston.”

15 “Forfeited to Boston.”

16 “Forfeited to Boston.”

17 “Ban Suspends Again,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1902.

18 “Ban Suspends Again.”

19 “Baseball Change Expected: McGraw’s Tilt with Ban Johnson May Let New York Secure Him as Manager,” New York Times, July 3, 1902.

20 “M’Graw Has Release,” Baltimore Sun, July 9, 1902.

21 Jimmy Keenan, “Joe Kelly,” Society for American Baseball Research, sabr.org/bioproj/person/17b00755, accessed November 15, 2019,

22 Keenan.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 9

Boston Americans 4

8 innings

American League Park

Baltimore, MD

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.