June 28, 1914: Honus Wagner becomes second major leaguer to join the 3,000-hit club

Honus Wagner was one of the greatest players in baseball history. Bill James’s 2001 New Bill James Historical Abstract listed the Pennsylvania native and longtime Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop as the second best player of all time, with only Babe Ruth ranked ahead of him.1 Elsewhere, James wrote, “Wagner was a legendary figure in that era, perhaps as close as anyone has ever been to being universally regarded as the best player in the game.”2

Honus Wagner was one of the greatest players in baseball history. Bill James’s 2001 New Bill James Historical Abstract listed the Pennsylvania native and longtime Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop as the second best player of all time, with only Babe Ruth ranked ahead of him.1 Elsewhere, James wrote, “Wagner was a legendary figure in that era, perhaps as close as anyone has ever been to being universally regarded as the best player in the game.”2

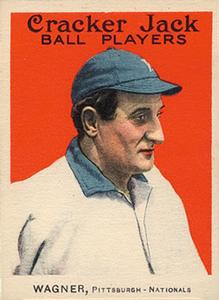

In spite of an ungainly build – Wagner was barrel-chested, with huge hands, and bowed legs – he was a tremendous athlete with great speed.3 As of 2022, he ranked third all-time with 252 triples and 10th with 723 steals. He was also a great hitter, with a .328 lifetime batting average and – although the exact total varies by source – more career hits than all but seven other players in major-league history. Wagner may be best known by many baseball fans as the player with the most valuable baseball card in history, a value driven both by the scarcity of the American Tobacco Company’s T206 card and Wagner’s extraordinary talent.4

Wagner debuted in the major leagues in 1897 with the Louisville Colonels, then moved to the Pirates after the 1899 season. Finishing in the National League’s Top 10 in hits in every season but one from 1899 through 1912, he recorded his 3,000th career hit in 1914, at the age of 40.

Exactly when Wagner reached the 3,000-hit milestone, joining Cap Anson as the second member of that club, is a matter of dispute. Newspaper coverage of the Pirates’ 3-1 loss to the Philadelphia Phillies on June 9, 1914, said Wagner recorded his 3,000th career hit in that game, a ninth-inning double against Philadelphia’s Erskine Mayer. “Old Bismarck Reaches 3,000th Safety Mark After 17 Years of Wonderful Batting,” a headline in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times proclaimed.5

As of 2022, several authoritative sources, including the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Major League Baseball, follow the contemporary record books and recognize June 9, 1914, as the date of Wagner’s 3,000th hit.6 These sources credit Wagner with 3,430 career hits.

Other prominent references, however, place Wagner’s milestone later in the month. The Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, first published in 1969, 14 years after Wagner’s death, conducted its own research on seasons before 1903, before official NL statistics existed. Determining that Wagner had fewer hits in several of those seasons than previously calculated, Macmillan set his career hit total at 3,420. In the twenty-first century, Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org have followed Macmillan’s data in developing their baseball history databases.7

By this count, Wagner’s celebrated hit of June 9 was only the 2,990th of his career, and he instead got number 3,000 in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds on June 28, nearly three weeks later.8

Wagner’s Pirates had won the World Series in 1909, after a 110-win season with a .724 winning percentage. They had been competitive in the NL the next few years, finishing third twice and second once, before falling to fourth at the end of the 1913 season. They had not had a losing season since 1898, two years before Wagner’s arrival.

Pittsburgh won 15 of 17 games to start 1914 and led the NL by four games on May 25 after a victory over the Brooklyn Robins. But the Pirates had played poorly for about a month after the win against Brooklyn, going 8-20 (with one tie) over the next 29 games.

The Cincinnati franchise had struggled over the previous decade, never finishing above third after 1904, and was seventh of the eight NL teams in 1913. Like the Pirates, the Reds had spent time in first place earlier in 1914 before slumping. Cincinnati’s 26-15 record on June 1 had tied the New York Giants for the top spot, but the Reds had dropped seven in a row before Pittsburgh’s visit. Going into the doubleheader, both teams were one game over .500, and tied for third place, six games behind the league-leading Giants.9

In the first game of the day, the Pirates led 6-2 going into the bottom of the ninth, but the Reds scored five runs in the ninth to win, 7-6. Wagner was held hitless in three at-bats.

Right-hander Marty O’Toole started the second game for Pittsburgh. The Pirates had paid a record $22,500 in 1911 to obtain O’Toole’s services, but his arm had been damaged by overuse, and O’Toole was generally ineffective for the Pirates. By 1914 the 25-year-old Washington native was being referred to as the “Lemon.”10 O’Toole was 0-1 with a 5.47 ERA in seven appearances going into the start against the Reds.

Rookie Pete Schneider, the youngest player in the NL in 1914, started for the Reds, nearly two months before his 19th birthday. Schneider had starred that year for the Seattle Giants of the Northwestern League, going 12-2 with a 1.43 ERA. He had received $571 in advance money from the Chicago Whales of the Federal League but had not signed a contract with the Whales. Schneider had also been courted by the Reds, and when he decided to play for Cincinnati, he had to return the advance money to the Whales.11 Schneider was making his third appearance, and first start, for Cincinnati. He had no won-lost record and a 4.91 ERA entering the game. There were 11,000 fans on hand to witness the action.

Displaying what the Cincinnati Enquirer described as “dazzling speed and a curve ball that would do credit to Babe] Adams or Bert Humphries,”12 Schneider set down the first two Pittsburgh batters to open the game before second baseman Jim Viox beat out a groundball to shortstop for an infield hit.13 Wagner had his first shot of the game at his 3,000th hit but flied out to left field for the third out.

After O’Toole set the Reds down in order in the bottom half of the first, Pirates first baseman Ed Konetchy walked to open the second and reached second base with two outs when Schneider’s pickoff throw got past Dick Hoblitzell at first. Konetchy then tried to steal third, but Reds catcher Tommy Clarke threw him out to end the inning.

Cincinnati went ahead in its half of the second. Heinie Groh, the Reds’ second baseman and an emerging star at age 24, singled with one out and went to third on Hoblitzell’s single. Wagner picked up the force at second on a groundball by Harry LaRoss as Groh scored for a 1-0 lead.

That was all the Reds managed against O’Toole, but Schneider was even better. Through six innings, Viox’s first-inning single was Pittsburgh’s only hit, and the first two Pirates to bat in the seventh were retired, bringing up Wagner, who had flied out again in the fourth.

Wagner singled to center, giving him 3,000 career hits under the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia’s count. But he advanced no farther, as Konetchy popped up for the third out.

Outstanding defense by Wagner – what the Pittsburgh Post described as a “leaping pickup and throw” on a bouncer, then a “[chase] into left field” to catch a fly ball – kept Cincinnati off the scoreboard in the bottom of the seventh.14

Schneider had to hold off two last Pittsburgh threats to preserve the shutout. With two outs in the eighth, he walked pinch-hitters Joe Leonard and Ham Hyatt. Speedy 24-year-old left fielder Max Carey, early in his Hall of Fame career as one of the game’s top contact hitters and baserunners, grounded to second, and “was barely beaten out by Groh’s toss” to first for the final out.15

In the top of the ninth, former Red Mike Mowrey led off with a single, and Viox sacrificed him to second. The tying run was in scoring position as Wagner batted against Schneider, born in 1895, the same year as the great shortstop’s professional debut. But Schneider was up to the challenge, retiring Wagner on a popup, then fanning Konetchy on a curveball to close out his first major-league win. “[Schneider’s] first start in the big show must surely be labeled an artistic success,” the Cincinnati Enquirer concluded.16

Wagner finished 1914 with a .252 batting average, which turned out to be the lowest of his career; the Pirates came in at 69-85-4 and in seventh place. He played through 1917, recording his final major-league hit – number 3,430 or 3,420, depending on the source – on September 3 against the Reds, as he finished his 18th season in Pittsburgh.

Regardless of whether Wagner’s 3,000th career hit happened on June 9, 1914, in Philadelphia or 19 days later in Cincinnati, he was still the second player in the history of the game to reach the 3,000-hit threshold, and the first in the twentieth century. Unlike Anson, whose lifetime statistics were similarly challenged by subsequent research, there is no question that his career hit total exceeded 3,000.17 Napoleon Lajoie became the third man to reach the 3,000 threshold, just three months after Wagner in 1914.

Author’s note

While I was in the process of writing this article, my family and I took a vacation to New York City. We visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the trip. Unbeknownst to me, the museum possesses, and displays, items from the extensive baseball card collection of Jefferson R. Burdick.

One of the highlights of the collection on display is the famous Honus Wagner card mentioned in this article. It was interesting to see the card in person. I hadn’t realized how small it is, only about one inch by three inches. It was a pleasant coincidence to see the card after doing the research for an article on Wagner.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to John Fredland for his suggestions and revisions to the first draft of this article. The final product is significantly improved because of his input. The article was fact-checked by Evan Katz and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used Baseball-Reference.com for team, season, and player pages and logs and the box scores and play-by-plays for this game.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CIN/CIN191406282.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1914/B06282CIN1914.htm

Notes

1 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

2 Bill James, “Baseball’s Best Player,” Bill James Online, https://www.billjamesonline.com/article151/, (last accessed March 15, 2022).

3 Jan Finkel, “Honus Wagner,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/honus-wagner/ (last accessed March 14, 2022).

4 Dan Hajducky, “T206 Honus Wagner Baseball Card Sells for $6.606 Million, Shattering Previous Record,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/32031670/t206-honus-wagner-baseball-card-sells-6606-million-shattering-previous-record (last accessed March 14, 2022).

5 James Jerpe, “Mayer Beats Pirates, but Wagner Gets Hit: Old Bismarck Reaches 3000th Safety Mark After 17 Years of Wonderful Batting – Crowd Gives Mighty Cheer – Phillie Pitcher in Form,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, June 10, 1914: 10.

6 National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, “The 3,000-Hit Club, Honus Wagner,” http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/3000_hit_club/wagner_honus.htm (last accessed March 15, 2022).

7 Mike Lynch, “Explaining the Honus Wagner Career Hits Discrepancy,” Sports-Reference.com, https://www.sports-reference.com/blog/2014/07/explaining-the-honus-wagner-career-hits-discrepancy/ (last accessed March 15, 2022).

8 Tom Ruane, “A Retro-Review of the 1910s,” Retrosheet.org, https://www.retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1910_art.htm (last accessed March 15, 2022). When following this count, Wagner attained 1,000 hits in his 755th game on September 6, 1902. It took him 769 more games to get to 2,000 hits; he reached that milestone on June 27, 1908.

9 The doubleheader was a single-day stop in Cincinnati, between the Pirates’ four-game home series with the St. Louis Cardinals that concluded on June 27 and a three-game set in St. Louis opening a day later. At the time, Pennsylvania law forbade Sunday baseball, and the Pirates often scheduled one-day visits to other NL cities. The date in Cincinnati was originally scheduled as a single game, but a May 4 rainout resulted in the doubleheader.

10 Dick Thompson, “Marty O’Toole,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/marty-otoole/ (last accessed March 16, 2022).

11 “Pitcher Schneider Signed,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1914: 15.

12 Jack Ryder, “Hopped Back Into Second Place: Reds Recover Form and Swat Pirates Twice,” June 29, 1914: 9.

13 The game description is taken from this newspaper account of the contest: Ed. F. Balinger, “Pirates Fall Twice Before Red Brigade,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 29, 1914: 8.

14 Balinger.

15 Balinger.

16 Ryder, “Hopped Back Into Second Place.” Schneider pitched in 207 games for the Reds and New York Yankees from 1914 through 1919, finishing his career with a 59-86 record and a 103 ERA+.

17 Bill Felber, “September 19, 1897: Cap Anson’s 3,000th Hit? SABR Baseball Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-19-1897-cap-ansons-3000th-hit/ (last accessed March 19, 2022).

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 1

Pittsburgh Pirates 0

Game 2, DH

Redland Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.