May 1, 1883: Philadelphia returns to National League for first game in Phillies franchise history

At the end of the 1876 National League season the Philadelphia and New York teams failed to travel west for scheduled road trips. Both teams were expelled from the league and those cities would be without National League base ball for the next six seasons.

At the end of the 1876 National League season the Philadelphia and New York teams failed to travel west for scheduled road trips. Both teams were expelled from the league and those cities would be without National League base ball for the next six seasons.

On May 1, 1883, under hazy skies with a temperature of 59 degrees and a slight wind,1 the Philadelphia team in the National League dropped a 4-3 decision to the Providence Grays at Recreation Park. There is no evidence that there were any pregame festivities on that Tuesday afternoon to mark the occasion for the 1,200 fans attending the first game in the history of the Philadelphia Phillies franchise.2

Al Reach, a sporting goods magnate who had been a star player in the old National Association from 1871 to 1875, and John Rogers, a local attorney and politician, had been granted the National League franchise after the Worcester, Massachusetts, franchise quit the league on December 6, 1882.3

Recreation Park was situated between 24th and 25th Streets from Ridge Avenue to Columbia Avenue in North Philly, 2½ miles from City Hall and downtown Philadelphia. Its dimensions were extremely shallow when compared to today’s standards: 300 feet to left field, 331 feet to center, and 247 feet to right.4 Built in 1860, the ballpark was rebuilt during the winter of 1882-83 in anticipation of the new ballclub. This work increased capacity to as many as 6,500 fans, with wooden grandstands added along with a new playing surface.5

This would be the Phillies’ first home and would remain so for the first four seasons of their existence. The City of Philadelphia has placed historical markers at the club’s other former home sites of Baker Bowl (1887-1938), Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium (1938-70), and Veterans Stadium (1971-2003), but one will find none anywhere around this historic first home location.6

For the first seven seasons the team was referred to by the geographical designation of the Philadelphias or by the nickname Quakers, with Phillies also being used on occasion.7 The name Phillies became a formal part of the club’s identity in 1890 and remains the longest continuous one-city nickname in professional sports history.8

The Providence Grays, who visited Philly for that first 1883 game, were a strong ballclub. They finished 58-40 and in third place, managed by a former great player, Harry Wright, who had previously skippered the Boston Red Stockings to six pennants. Known to many as the father of professional baseball, Wright switched teams the following year and managed the Phillies for a decade from 1884 to 1893.9

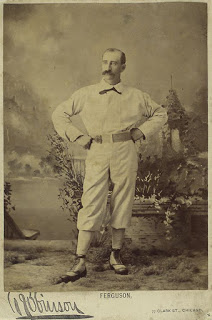

The Phillies who stepped on to the field at Recreation Park on that first day played under manager and second baseman Bob Ferguson. Ferguson didn’t last the year, replaced after just 17 games and a 4-13 start. It got no better, with the club going 13-68 under third baseman-outfielder Blondie Purcell.10

The overall 17-81 final record left the Phillies at the bottom of what was then an eight-team National League. Not only were they 46 games out of first place; they were also a distant 23 behind the next-lowest club, the seventh-place Detroit Wolverines.11

The Providence starting lineup:

- Paul Hines CF

- Joe Start 1B

- Jack Farrell 2B

- Arthur Irwin SS

- John Cassidy RF

- Cliff Carroll LF

- Charles Radbourn P

- Jerry Denny 3B

- Barney Gilligan C

The Grays’ big star was pitcher Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, who won 48 games that year at age 28 in what was his third of 11 big-league seasons. He eventually landed a place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In that 1883 season, Radbourn was the starting pitcher for 68 of the Grays’ 98 games. He is the first known athlete to give the middle finger in a photograph in 1886 while posing with his team, the Boston Beaneaters, for an Opening Day team photo at New York’s Polo Grounds.12

Hines finished his career with a lifetime .302 average over 20 seasons. Start was the first native of Rhode Island to play in the big leagues. Irwin became the first player to wear a glove, in 1883 after he injured two fingers. After he died, it was found that he had two families with two different wives in two different cities.13

The Philadelphia starting lineup:

- Blondie Purcell LF

- Bill McClellan SS

- Jack Manning RF

- Bob Ferguson 2B

- Fred Lewis CF

- Bill Harbridge 3B

- John Coleman P

- Frank Ringo C

- Sid Farrar 1B

Ferguson’s nickname was “Death to Flying Things,” which he earned due to his ability to catch fly balls during the no-gloves era. In addition to being the team’s first manager, on that day Ferguson was also the first switch-hitter in the sport.14 Ringo was an alcoholic who would tragically take his own life six years later at age 28 with an intentional morphine overdose. He had previously caught Coleman, who was a Philadelphia native, when the two were batterymates with Peoria of the Northwestern League.15 Farrar hit just .253 over seven seasons with the Phillies. His daughter, Geraldine Farrar, born the year before his arrival in Philadelphia, became one of the most popular opera stars in the world.

Purcell started the bottom of the first with a single to left-center field for the first base hit in Phillies franchise history. The Philadelphia Inquirer article implies that McClennan hit a ball over the right-field fence for a double.16 It may have been a Recreation Park ground rule in those days since the fence was only 247 feet from home plate. Manning then grounded a ball to Farrell at second base, bringing home Purcell with the first run scored in Phillies history. Ferguson hit a ball back to Radbourn, with McClellan sliding home to beat the throw for a second run. Lewis then hit a ball to Irwin, who flipped the ball to Farrell, beginning a classic 6-4-3 double play to end the inning.17

There was no further scoring until the bottom of the seventh inning. Lewis made it to first base on an error by Grays second baseman Farrell. A hit by Harbridge moved Lewis to second. Coleman grounded out to Start at first base, and on the play Lewis was also put out at third to complete a double play. Ringo then hit a ball to left field, where Carroll misjudged it, allowing Harbridge to score. The Phillies had themselves a 3-0 lead. But as in so many games to follow for the team, the lead did not last.

The Grays scored all of their four runs in the top of the eighth inning. Radbourn led off with a walk, Denny singled, and Gilligan singled to load the bases. Hines then ripped a bases-clearing double to tie the game at 3-3. Start grounded out to Farrar at first, with Hines moving to third base. Farrell drove in Hines with the go-ahead run, putting Providence on top by 4-3. Irwin finished the inning by hitting the ball to Farrar at first. Only three of the runs were earned without any formal explanation by the official scorer.18 When Hines hit his double, a miscue must have happened to allow the third run to score when the bases were cleared. This was the first “crooked inning” ever recorded against the Phillies.19

Now trailing 4-3, the local squad attempted a comeback in the eighth inning. Purcell made it to first on a single but sustained a sprained ankle. He continued to play because the Grays would not allow the Phillies to use a courtesy runner. Beginning what evolved into a long-standing Philadelphia sports fan tradition, the attendees that day did not take kindly to the lack of accommodation by the Grays. They “vigorously hissed” the opposition.20 Start then made an error allowing McClellan to reach base and the hobbling Purcell to second. After Manning and Ferguson flied out to right and left field respectively, Grays catcher Gilligan allowed a passed ball. Purcell tried to advance but was called out at third base, though the Inquirer’s writer thought he was safe. The Philly fans hissed again at this call.21 Had Providence allowed the courtesy runner, that runner might have been safe, and the outcome might have been different. Providence won the game by the final 4-3 score. Despite yielding only six hits, Coleman suffered the first of what would become 48 losses on his record during that first Phillies season.

The loss on May 1, 1883, was the harbinger of things to come for the franchise. The team went just 56-154 over their first two seasons in the National League. During a long, horrific stretch beginning in 1918, the Phillies and their fans suffered through a disastrous period during which the team registered losing campaigns in 30 of 31 years, often finishing at the bottom of the league. As of the conclusion of the 2019 season, the Phillies had now lost exactly 11,000 games, more than any other team in baseball history.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Weather,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 1, 1883.

2 “The Season Opened Everywhere,” New York Times, May 2, 1883.

3 Matt Veasey, “First Game in Philadelphia Phillies History Franchise History,” Phillies Bell (2020): philliesbell.com/2020/05/01/first-game-in-philadelphia-phillies-franchise-history/: Retrieved May 2, 2020.

4 Veasey.

5 Rich Westcott, “Philadelphia Phillies: A Vibrant History,” The National Pastime 43 (2013): sabr.org/research/philadelphia-phillies-vibrant-history, Retrieved April 28, 2020.

6 Veasey.

7 Westcott; Veasey.

8 Westcott; Veasey.

9 Veasey.

10 Veasey.

11 Veasey.

12 Erik Brady, “Middle Finger Often in the Middle of Sports Controversy,” USA Today, October 26, 2017. usatoday.com/story/sports/2017/10/26/middle-finger-often-middle-sports-controversy/804550001, Retrieved May 2, 2020.

13 Eric Frost, “Arthur Irwin,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/e5e7bfa4, Retrieved April 30, 2020.

14 Brian McKenna, “Bob Ferguson,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/df8e7d29, Retrieved April 30, 2020.

15 Veasey.

16 “Providence Wins,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 2, 1883.

17 “Providence Wins.”

18 “Providence Wins.”

19 Veasey.

20 “Providence Wins.”

21 “Providence Wins.”

Additional Stats

Providence Grays 4

Philadelphia Quakers 3

Recreation Park

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.