May 19, 1918: Senators’ first Sunday game draws record crowd in Washington

Paid-admission Sunday baseball came with relative ease to the District of Columbia. On May 14, 1918, “the District Commissioners, after careful consideration of the needs of the Capital, lifted the [Sunday] ban on professional sports.”1 Without the extensive legal, referendum, and legislative maneuvering that was ultimately necessary to bring Sunday baseball to New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania,2 “the action of the Commissioners [was] not in response to any request or demand by outside parties. They were not consulted, nor or even informed that the new rule was to be issued until its announcement.”3

Paid-admission Sunday baseball came with relative ease to the District of Columbia. On May 14, 1918, “the District Commissioners, after careful consideration of the needs of the Capital, lifted the [Sunday] ban on professional sports.”1 Without the extensive legal, referendum, and legislative maneuvering that was ultimately necessary to bring Sunday baseball to New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania,2 “the action of the Commissioners [was] not in response to any request or demand by outside parties. They were not consulted, nor or even informed that the new rule was to be issued until its announcement.”3

The United States had entered World War I in April 1917, two years and nine months after the conflict erupted in Europe. Nearly a year into US participation, the national capital was consequently filled with soldiers and civilian military workers – the commission determined “baseball will be beneficial to the thousands of war workers here.”4 Washington was already permitting movie theaters to operate on Sundays; additional public-amusement options like baseball were also cited as a possible deterrent to increases in sales of illicit liquor in the District.

Because the Yankees’ game scheduled for April 18 in Washington had been rained out,5 sportswriters expected the New Yorkers to play the first Sunday game against the Senators on May 19, just five days after Sunday games were authorized. But American League czar Ban Johnson asked the Cleveland Indians to play the game, “as a return favor for all the one-game road trips the Senators made to Cleveland for Sunday games since 1911 when Sunday games were legalized there.”6 This scheduling also provided a convenient makeup, as the Indians had themselves been rained out in Washington on May 13. Cleveland, on an Eastern road swing, was relatively close by in Philadelphia the day before the first-ever Sunday game in Washington.7

On May 11 the Senators’ ace, Walter Johnson, had outdueled Cleveland’s Jim Bagby Sr. 1-0 at Washington’s American League Park.8 Then, four days later, he went 18 innings against Lefty Williams of the White Sox in another 1-0 win. Johnson was reported to have “caught cold and felt the effects of the grueling struggle”9 but the assumption was that he would pitch this watershed game, and even the early editions of the game-day newspapers reported that he was still expected to start for Washington.

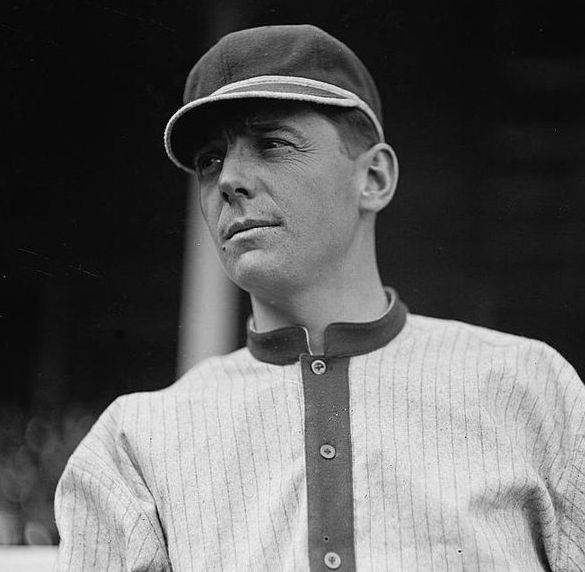

He didn’t. Senators manager Clark Griffith gave 27-year-old right-hander Doc Ayers the starting assignment against Stan Coveleski, Cleveland’s ace,10 as 15,352 civilians and 2,000 soldiers from military camps near Washington settled in for the 3:30 p.m. first pitch, pushed back a half-hour to allow for the expected attendance surge.11 This included “[s]enators, representatives, diplomats, officers from practically all the allied armies, society folk rubbing elbows with Mr. Average man and his wife or sweetheart [as well as] a justice of the Supreme Court,” and constituted “the biggest crowd that ever saw a ball game in the District of Columbia.”12 The thinking of the District Commission about Sunday entertainment had been verified.

The assemblage was treated to a back-and-forth pitchers’ duel replete with defensive gems and lapses. Clyde Milan got the game’s first hit with two outs in the Washington first when he legged out an infield roller toward Cleveland second baseman Ray Chapman. He reached base again in the third when Coveleski botched his comebacker; Doc Lavan, who had singled ahead of Milan, advanced to second on the play but was forced at third base on Howie Shanks’ groundball. The next batter, Joe Judge, hit a ball that Chapman couldn’t handle in the infield, but the Indians got out of the inning when he recovered to throw Milan out at the plate.13

Washington collected two more hits in its fourth inning, but efficient infield force-out work by the Indians kept the game scoreless.

Meanwhile, Ayers and his submarine14 spitball rolled along for the Senators without allowing a hit until, with one out in the Cleveland fifth inning, Terry Turner reached on an error by Lavan and Steve O’Neill singled to right field, moving Turner to third base. But what had looked like a good scoring opportunity ended when Coveleski’s dribbler forced O’Neill at second base. as Turner stayed at third on the play; Ayers bore down and ended the inning, getting Smoky Joe Wood15 to foul out to Eddie Ainsmith.

Each spitballer16 recorded one-two-three innings in the sixth to keep the game scoreless. The crowd was apparently getting restless, as the writer who recorded the Washington Herald’s play-by-play account17 noted “[they] stood up in the wrong half of the seventh.” In its half of the inning, Cleveland managed two more hits separated by a pair of outs, but Coveleski popped out to second base to thwart a rally.

The Senators advanced Burt Shotton as far as third base with two outs in their seventh; Coveleski got Milan to roll out to Chapman to keep the plate unsullied. The only double play in the game – Lavan to Ray Morgan to Judge – ended a mild Indians’ threat in the eighth fueled by a walk and a Washington error. Coveleski responded with a one-two-three eighth against the Senators.

Some nifty fielding by Lavan for Washington and Cleveland first baseman Rip Williams in the ninth inning carried both pitchers through regulation with the game still scoreless.

The Senators looked to be in business in the bottom of the 10th when a bobble and throwing error by Williams left leadoff hitter Shotton on second base. But yet another force out at third base, a force at second, and Coveleski’s sure handling of a hot comebacker by Shanks erased the threat.

Ayers had to deal with two Indians baserunners in the top of the 11th inning on an error and a walk but got O’Neill on a popup to third base to wiggle out of the jam. This time, Coveleski cruised through Judge, Morgan, and Eddie Foster when Washington batted in the bottom half.

Coveleski’s teammates nearly broke the deadlock in the top of the 12th. With two outs Chapman legged out a roller to shortstop. Tris Speaker singled him to third, then stole second base. Cleanup hitter Braggo Roth stood in, but Ayers, equal to the challenge, retired him on a groundball to second base.

It had been five innings since the crowd had enjoyed its early stretch but the Senators got them to their feet again quickly in their half of the inning. Frank “Wildfire” Schulte led off pinch-hitting for Ainsmith and beat out an infield hit. Ayers bounced back to Coveleski, but a would-be double play dissolved when he threw wildly to second base. With no outs and runners on first and second, Cleveland cut down Schulte at third on Shotton’s comebacker to Coveleski, then got Lavan as Ayers moved to third and Shotton to second.

The stage was set yet again, and this time Milan “furnished the big thrill. He sent a sizzling hit over the third-base bag that gave the [Senators] a 1-0 victory.”18 Ayers, who had pitched around errors all day, scored the only run he needed to get his third win against two losses in the young season. Coveleski had also pitched masterfully given his teammates’ errors; it was his own error that did him in.

This was still May, fewer than 30 games into the season, and both teams were bouncing around .500. Cleveland went on to finish 73-54 and 2½ games behind the American League pennant-winning Boston Red Sox. The Senators, 72-56, were another game and a half back in third place.

Including this first-ever game, Washington played 12 Sunday home games in 1918. They adapted well to this new concept, giving their fans wins in nine of the 12. Those wins included a doubleheader sweep of the White Sox on August 25.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for box scores, team and player pages, and schedule logs for the 1918 season. The detailed play-by-play appearing as a sidebar to the game story in the May 20, 1918, Washington Herald, accessed through Newspapers.com, was especially useful.

baseball-reference.com/boxes/WS1/WS1191805190.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1918/B05190WS11918.htm

Notes

1 “Sabbath Ban Lifted on Own Initiative by Commission,” Washington Times, May 14, 1918: 1, 19.

2 The first legally sanctioned Sunday games were played in New York City in 1919, Boston in 1932 and in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in 1934. Charlie Bevis, Sunday Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2003), 272.

3 “Sabbath Ban Lifted.”

4 “Soldiers to Be Favored as Sabbath Ban Is Lifted,” Washington Post, May 15, 1918: 10.

5 Baseball Results and Standings, Boston Post, April 19, 1918: 11.

6 Bevis, 193.

7 The Yankees were at home in New York, playing a series with St. Louis. With Sunday games not permitted in New York until 1919, the Yankees had an open date on May 19, 1918.

8 Opened in 1911, the ballpark was located at 7th Street and Florida Avenue. In 1918 newspaper coverage it was referred to either as American League Park or as the Florida Avenue grounds. Although Clark Griffith managed the Senators in 1918 and the team was routinely referred to as the “Griffmen,” Griffith did not have a controlling ownership interest in the team until 1920; only then did the ballpark become known as Griffith Stadium. Griffith Stadium entry, AndrewClem.com, accessed September 14, 2018.

9 Denman Thompson, “Record Crowd Is Expected at Base Ball Park Today,” Washington Evening Star, May 19, 1918: 43.

10 Coveleski went on to win 22 games for the 1918 Indians, starting a string of four straight seasons with 20-plus wins. In December 1924 he was traded to Washington, where he won 20 games for the 1925 pennant-winning Senators. Coveleski was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969 by the Veterans Committee.

11 The soldiers received complimentary tickets. Temporary seating had been installed “in front of the grandstand and pavilions, where the men in uniform will get a close-up view of the proceedings.” Thompson, “Record Crowd.”

12 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Milan Hits Nationals to Victory in Twelfth as More Than 17,000 Look On,” Washington Post, May 20, 1918: 8.

13 Errors were definitely a feature of this game, which took 2 hours 29 minutes, an eternity in the Deadball Era, to complete. Each team had six miscues. Because the teams totaled only six walks and strikeouts between them, the ball was usually in play, most often in the infield. Several force outs at third base resulted – something rarely seen in today’s “three true events” (home runs, strikeouts, walks) baseball.

14 A submarine pitch is delivered from an even lower angle than a side-arm pitch. In the Deadball Era (1901-20) writers often referred to it as “underhand.” As of 2020, there were several submarine pitchers active in the major leagues, but, presumably, no spitball pitchers. The spitball was legislated out of baseball in 1920 when Cleveland’s Ray Chapman died after being hit in the head by a spitball from New York Yankees’ submarine pitcher Carl Mays. By way of a “grandfather” provision, baseball allowed all spitball pitchers who had been active in 1920 to continue to use the pitch until their retirement.

15 Smoky Joe Wood won 117 games as a pitcher with the Boston Red Sox from 1908 through 1915. In February 1917 Boston sold his contract to Cleveland, where, at age 27, he became an outfielder and utility player. He hit .297 in six seasons with Cleveland.

16 Coveleski also threw a spitball. See Daniel R. Leavitt, “Stan Coveleski,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed September 24, 2018.

17 Washington Herald, May 20, 1918: 8.

18 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Milan Hits Nationals to Victory.”

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 1

Cleveland Indians 0

12 innings

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.