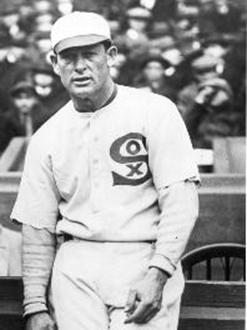

May 26, 1907: Big Ed Walsh tosses rain-shortened no-hitter in farcical game

“Rain, hail, thunder, lightning, and flood were summoned to the rescue of the New Yorkers,” opined the Chicago Tribune about the horrendous weather conditions that threatened to wash out the White Sox’ bombardment of the Highlanders in the Windy City.1 While Mother Nature unleashed her fury, the visitors employed stalling tactics, hoping the field would become unplayable. “The game was a farce after the third inning,” lamented the New-York Tribune.2 Lost in the mayhem and an umpire’s threat to award a forfeited victory to the Pale Hose was Big Ed Walsh’s abbreviated five-inning no-hitter.

the White Sox’ bombardment of the Highlanders in the Windy City.1 While Mother Nature unleashed her fury, the visitors employed stalling tactics, hoping the field would become unplayable. “The game was a farce after the third inning,” lamented the New-York Tribune.2 Lost in the mayhem and an umpire’s threat to award a forfeited victory to the Pale Hose was Big Ed Walsh’s abbreviated five-inning no-hitter.

Chicago had been blanketed by dark skies and battered by rain and gusty winds for five days, wreaking havoc on the originally scheduled four-game series between the reigning World Series champion White Sox and the Highlanders. After the first two games were postponed, the rain subsided just enough to enable player-manager Fielder Jones’s club to defeat the intruders, 3-1, to improve its record to 22-10, though its lead in first place had dropped to just one game. Skipper Clark Griffith’s fourth-place Highlanders (15-14) were 5½ games back.

The game featured two of baseball’s most prolific spitballers. The Highlanders’ Al Orth, known as the Curveless Wonder for his perplexing wet ones that broke sideways like a curve instead of dropping straight down, was coming off a career year, leading the majors with 27 wins. Described as “one of the most famous ‘slow ball’ pitchers” in major-league history, 34-year-old Smiling Al was 7-3, pushing his career mark to 195-158 in parts of 13 seasons.3 The White Sox’ 26-year-old Ed Walsh had emerged the previous season as one of the sport’s most dominant hurlers. Notwithstanding his pedestrian record (17-13), Walsh led the majors with 10 shutouts and posted a 1.88 ERA in his first full season as a starter, capped off by two stellar victories over the Cubs in the World Series. Possessing a powerful heater, Big Ed entered the game with a 4-1 record and a 35-20 lifetime record so far.

Despite the threat of precipitation, an “overflow crowd” packed the 15,000-seat South Side Park, located at 39th Street (now called Pershing Road) and Wentworth Avenue on Chicago’s South Side.4 Walsh recorded two quick outs and then had a hiccup, walking both Kid Elberfeld and Hal Chase. Big Ed’s fit of wildness continued as he uncorked two wild pitches, resulting in the Highlanders’ only tally of the game.

“The orgy began,” jested the New York Sun, when the White Sox came to bat in the bottom of the first.5 Leadoff hitter Ed Hahn was plunked and moved up a station on Jones’s sacrifice bunt. After Elberfeld threw away Frank Isbell’s grounder to short, Jiggs Donahue hit sharply to third. The ball caromed off George Moriarty’s mitt while Hahn raced home to tie the score. George Davis smashed another one to the hot corner; Moriarty fumbled it and Isbell scored. Patsy Dougherty singled to right-center, driving in Donahue and sending Davis to third. The White Sox executed an exciting double steal, with Dougherty sliding home for the fourth run just as George Rohe fanned.

After two uneventful, scoreless innings, thunder began to roar in the top of the fourth, giving hope to the Highlanders that the game might be called. In a race against the rapidly darkening skies and imminent downpour, Big Ed worked quickly, retiring the side in order.

The chaos, indeed outright anarchy, in the bottom of the fourth is difficult to imagine from modern twenty-first-century perspectives. A light drizzle began and gradually intensified. Stalling for time, Orth meticulously went through his motions, taking as much time between pitches as possible. Following Daugherty and Rohe’s consecutive singles, a heavy downfall erupted, sending players off the field.

With gusting winds, thunder, lightning, and buckets of rain, it did not appear that the game would resume. Nonetheless, the downpour suddenly stopped after 10 minutes. “The instant the deluge ceased the umpires ordered the hostilities resumed,” reported the Tribune, and the Highlanders took position in a muddy infield and sopping wet outfield.6 “The field was a lake,” bantered the Sun.7

Clark Griffith, the Old Fox, had a trick up his sleeve. A pioneering pitcher with 237 victories, including 24 for the White Sox in the AL’s inaugural season, Griffith took the mound for the first time in 1907. At 37 years old, Griffith was in excellent shape and had logged 59⅔ innings the previous season with the Highlanders. Described as “slow and annoying” by the New York Times, Griffith attempted to delay the game in every possible way.8 He threw repeatedly to first base to force Rohe back to the bag, even though the latter wasn’t attempting to steal; Jones barked his frustrations. Griffith eventually walked Billy Sullivan deliberately to fill the bags. Walsh followed with a double to left, driving in two more runs. The Tribune suggested that Sullivan, in an attempt to end the game as quickly as possible, purposely passed third, forcing the Highlanders to tag him at home for the first out.9 Hahn “deliberately hit to [second baseman Jimmy] Williams” for another out, noted the newspaper.

The game took a bizarre turn at this stage with the two managers facing each other. Jones intentionally hit a slow roller back to the box. However, Griffith purposely let the ball roll through his legs. Elberfeld picked it up and as if in slow motion threw to first. An exceptional ballplayer and feisty manager, Jones must have been seething. He played his trump card and deliberately avoided touching first base and continued to second to force the inning’s last out. But the Highlanders refused to tag him. Amazed at what was transpiring, second-base umpire Jack Sheridan interrupted the proceedings and threatened to declare the game a forfeit and award the victory to the White Sox if Williams did not immediately tag Jones. Recognizing that the Highlanders would lose their share of the gate receipts if the game were forfeited, Griffith gave a sign to Williams, who tagged Jones for the final out. Walsh had crossed home well before the tag, but his run was nullified because Jones had not touched first.

Walsh retired the side in order in the top of the fifth to make the game official. “[A] mighty shout greeted the third out,” reported the Tribune about the crowd’s reaction to what was surely one of the most bizarre games the spectators had ever witnessed.10

The rain resumed when the White Sox came to bat in the fifth, leading 6-1. Isbell led off with a hit to center. Danny Hoffman retrieved the ball, slipped and fell, then heaved the ball from a sitting position, but Isbell reached second with a double.11 On third after Donahue’s groundout, Isbell was caught in a rundown when Griffith fielded Davis’s tapper to the mound. Isbell jockeyed, enabling Davis to reach second, then slid safely under Moriarty’s tag and scored. Davis stole third as the rain began to intensify. Donahue blasted a double, driving in Davis to increase the White Sox lead to 8-1.

A torrential rainfall erupted, sending the players scampering off the field for the second time. The “diamond was afloat” in five minutes, while shifting winds brought “hailstones bigger than Mauser bullets” that threatened lives, reported the Tribune.12 The grounds crew hastily removed the new World Series championship banner from a flagpole in the bleachers. As it became increasingly clear that the game could not resume even if the rain subsided, the umpires declared the game official. The time of game was 55 minutes.

Sportswriters in Chicago and New York focused on the weather and Griffith’s bizarre dilatory tactics in their game accounts. Walsh’s abbreviated no-hitter seemed to be an afterthought, and perhaps rightly so, considering that it was far from a memorable or overpowering performance, unlike his three one-hitters and a two-hitter with 12 punchouts in the World Series the previous season. Nonetheless, it was considered a no-hitter until September 1991, when the Committee for Statistical Accuracy altered the definition of a no-hitter to include only those that last at least nine innings and end with no hits. An estimated 36 abbreviated no-hitters were removed from the ranks, including Walsh’s.

Epilogue: Walsh finished the season with a 24-18 record and led the AL with a 1.60 ERA and the majors with 422⅓ innings pitched. Four years later, Walsh etched his name in baseball history by tossing the first no-hitter in the history of Comiskey Park, then called White Sox Park, which had opened in 1910. It was the only official no-hitter in the Hall of Famer’s career, during which he went 195-126 with 57 shutouts and a 1.82 lifetime ERA, the lowest in big-league history.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com and SABR.org:

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA190705260.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1907/B05260CHA1907.htm

Notes

1 Sy (Irving Sanborn), “Snatch Victory from the Clouds,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1907: 10.

2 “Yankees Beaten Again,” New-York Tribune, May 27, 1907: 8.

3 J.E. Wray, How to Pitch (1932) quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide To Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 329.

4 “Snatch Victory from the Clouds.”

5 “Sox Batter the New Yorks,” (New York) Sun, May 27, 1907: 5.

6 “Snatch Victory from the Clouds.”

7 “Sox Batter the New Yorks.”

8 “Yankees Drop Game Between Showers,” New York Times, May 27, 1907: 4.

9 “Snatch Victory from the Clouds.”

10 “Snatch Victory from the Clouds.”

11 “Notes of Game,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1907: 10.

12 “Snatch Victory from the Clouds.”

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 8

New York Highlanders 1

5 innings

South Side Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.